Let’s say you find yourself outside this summer with a glass of wine, on a patio or in a rented wedding tent, in the company of one or one thousand. If the night goes off well, everything will be where it’s supposed to be and you will unconsciously navigate the space seeing happy faces and renewing the bonds of friendship and family with that glass in hand, ignorant of the hive of activity making it possible. And as this ancient social lubricant glistens in your glass and slides down your throat, you may pause for a moment to consider the gift in your hands. You may even look to the wise words of others to help us understand why wine and the celebrations it accompanies seems so special.

Gisela Kreglinger is one of those experts, and her book The Spirituality of Wine makes a coherent defense of the long-standing relationship between the Christian tradition and wine. Her work is inflected by a personal connection to the subject too. She is a theologian who grew up on a vineyard, tending the vines as her family has for centuries. This kind of deep knowledge, in her hands as much as her thoughts, is evident in the care she takes deftly handling interviews, insights, and scholarship like grape clusters harvested for her paperback grand cru. The book would certainly be the definitive text on its subject were it named the Spirituality of Winemaking. But it is not, and the presumptions in that little slip give me pause, and maybe a bit of worry.

To lay my cards on the table, the reason this focus stands out to me is because I am one of the people it ignores. As Kreglinger wears two hats as theologian and winemaker, I wear the hats of theologian and hospitality industry veteran. I am the one who pops the corks, polishes your glasses, creates pairing guides, and cleans up when the party is over. When you see these things happen hundreds or even thousands of times in a restaurant or banquet hall, patterns and meanings emerge that are not apparent in the one-off dinner party in your home. These are the moments of anticipation, ecstasy, and nostalgia that are only noticed by the server.

For Kreglinger, the spirituality is in the wine itself, a rarefied quality imparted by the vintner as she shepherds the strange biology and chemistry of fermentation. Since she only speaks with winemakers, implicitly only the maker is fit to comment on what makes wine spiritual. Our attention to the gift is thus assumed to be mediated solely by the work of the winemaker. A secular clericalism is at work in this: The winemaker consecrates the final product, and then it is immediately ready to be received by the consumer. But the Protestant in me (and especially the Baptist) thinks this is woefully wrong. The whole process is spiritual all the way down, not just in the substance but also in the service, whether you’re running downstairs to pick which of the three bottles in your laundry room you want to open or you’re at a guided tasting at a restaurant. And an exclusive focus on the producer, the maker, valorizes what is easy to see and therefore easy to love in a way that is analogous to our cultural celebration of makers. Theology ignores service too, because on the left and the right academics connect the ancient virtue of hospitality with the home. Then, in a type of unexamined primitivism, we ignore the historical expansion from the home (oikos) to broader, connected economic life (oikonomia) as if markets were never invented, and we assume that hospitality is somehow cheapened the moment it involves money.

If wine is truly a gift (and I’d say it is), then the fullness of that gift is not achieved the moment it is bottled. “Value added” is economic shorthand for why the glass of wine you buy costs $8 when the bulk juice price is pennies on the bottle. But adding value is not only an economic activity; it is a layering of meaning, and as each layer reveals itself, another calls out, saying, “But wait . . . there’s more!”

This is true of all kinds of things we consume. Developing “discriminating” tastes has an ethical as well as aesthetic component. In The Omnivore’s Dilemma, Michael Pollan points to the koala bear, whose diet consists solely of eucalyptus leaves and therefore does not need to devote any effort to choosing its meals. We humans, however, confronted with the cornucopia of nature, must ask ourselves daily, What should we eat? This dilemma is the seed of food culture. Faced with the singular gift of wine, the question is not what but “when should we drink?” That tiny question will drive us to seek answers, for in vino veritas (and caritas). At what time? Accompanied by what food? In whose company? These questions of meaning move beyond the wine itself, and their answers are mediated by culture. That mediation is hard work, even if you never see the people paying deep attention to how it’s done. There are scores of behind-the-scenes figures that make it possible for you to raise a glass to your lips. Come with me and see how much more there is beyond the winemaker.

To the Wine

Even before wine leaves the vineyard there is a handoff from the winemaker to the maître de chai, or cellarmaster. This person decides how to blend different varietals to create the final product. It is for them to decide whether this Bordeaux should have more cabernet or merlot. Most importantly, they decide when a wine has been aged enough to be blended, bottled, and drunk. Why is this wine sold when it is three years old and not four? It is the cellarmaster that knows. Then the wine emerges, and once joined with its companions (in a process called assemblage), it is sent out into to the world. Determining readiness of wine, the fullness of time in which a gift is to be given, is a type of practical wisdom.

Once ready to be drunk, then the question of when takes on new meanings; this is the expertise of the sommelier. They are like life coaches, but for wine. “Drink this before a meal as an aperitif, drink that when you are eating pork, for the sake of God’s gift, never drink a big, red wine when you are eating oysters!” Curiously, while Kreglinger interviews dozens of winemakers, there is no evidence that she spoke to a single sommelier. Strange because just as surely as rot on the grapes can kill a wine, so to can that horrible pairing of Syrah and oysters, or oaked chardonnay with a spicy curry.

The pleasure of wine is not measured by the alcohol percentage, no matter what your wayward college years might have taught you. As you graduate from that simple thinking, the next fallacy to overcome it that the pleasure of wine is measured by the price of the bottle. But it is a sommelier who will tell you that the $200 bottle of Screaming Eagle Cabernet will be ruined by tuna, and ruin the tuna in turn. And it will be their knowledge that will guide you to the neglected wine from Bulgaria that will fit like a glove with the menu for your wedding and be cheaper than anything from France.

Sommeliers offer us the practical example of not begrudging the lesser gifts, even while possessing the knowledge that makes us appreciate the greater ones. They have the words and palate to help us discern the strange utterances of our taste buds when we try an expensive wine, while still knowing how to make a bottle of two-buck chuck sing with a meal. In my experience, the moment right before you begin to appreciate wine is the moment you feel an uncanny shift in how you interpret those “wine snobs” who can write books just describing how wine tastes and feels in your mouth. If you pay attention, and if the sommelier isn’t a hack, then it dawns on you that as crazy as everything they are saying sounds, it all makes sense. The wine really does smell like leather; you really can taste fresh strawberries in one wine and strawberry jam in another. And then you’re hooked. Walk with a forester through old growth or talk to a fly fisher while she’s tying a lure and you get the same effect. Sustained attention brings deep insight, and the depths of creation are infinitely fecund. Sommeliers are just another iteration of the response to this depth.

Kingly Gift in a Servant’s Hands

One of the strangest things in the formation of hospitality staff is the way they are trained to be the backup for other people’s good times. No matter why you are drinking wine, your server or bartender is there, on the surface, to get a paycheque. But even if that is the initial motivation, there is an internalization that happens as inevitably as the sore feet and stiff back. Servers begin to live a life conditioned to rejoice with those who rejoice, and being caught up in the joy of others is why many of my colleagues have turned the job they thought was putting them through university into an actual vocation. It’s difficult to explain, but good servers stay back until they see a small place to inject themselves for the purpose of facilitating your pleasure; they learn subtle cues to excel at what they do. You may not realize that how you fiddle with your wine glass when you are finished looks different from the way you fiddle when you want another pour, but a good server does. And you may not want to hold on to that last mouthful of wine in a glass from the reception, but the server knows your table is the type to order cheese instead of cake for dessert, so they save it in secret for the moment you want it. Thus, your experience is heightened.

One of the strangest things in the formation of hospitality staff is the way they are trained to be the backup for other people’s good times.

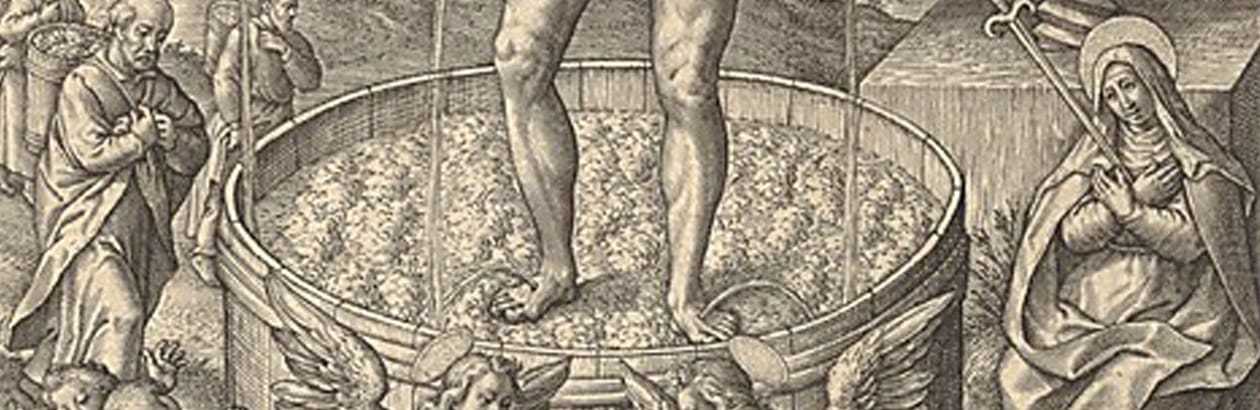

And servers do these things only to be forgotten. Oh sure, you might have one memory of a particularly transcendent meal where you connected on a personal level with a waiter, but for the most part, these foot soldiers of good times are faceless. Now consider the irony that Christians, followers of a God who took on the title of servant and who is vividly depicted as Christ the Winepress and whose blood is remembered as wine, would ever ignore the humble face filling our glass. We take for granted the servants standing next to us while praising the art and craftsmanship of the maker of a wine in a far-off vineyard.

If we are taught in Matthew 25 to know that whatever we do for the least of our fellow humans we do for God, how does that change our table manners? What if we are invited to the divine feast at the end of days only to discover that Jesus is the busboy?

As a final note, there is also the matter of what happens to wine if it is not consumed. What happens when a gift is wasted, when proffered hospitality is ignored? Wine’s death is not an annihilation; it doesn’t putrefy like meat or vegetables. Instead there is a fall from sweet gift into bitterness. The world of microbiology that gives us fermentation via yeast also gives us vinegar via acetobacter, which transform the alcohol molecules into acetic acid after only a few hours out in the open. We could attempt to repurpose this remnant, in our salad dressing or fruit fly traps, but these are mere consolations. At two in the morning, when the lights come on after your high school reunion, the exhausted servers on cleanup duty will go around the room and collect the partial leftover bottles for recycling. Over the night the wine has been anticipated and savoured, and then some of it forgotten. Servers see and collect wine that has died one death (to taste) and awaits the second death down the sinks. We cannot hope to recover lost wine. Once turned there is no going back. Or is there?

Maybe not in the here and now, but there is a patristic tradition that gives hope. This ancient biblical interpretation connects the first miracle of Jesus at the wedding feast in Cana to his being offered vinegar on the cross in a cruel reversal of the adage that when life gives you lemons, make lemonade. Christ offered the world choice wine, and the world soured it and gave it back. If that makes you want to drink for the wrong reasons, take heart from Gregory of Nazianzus, who said,

He is given vinegar to drink mingled with gall. Who? He who turned the water into wine who is the destroyer of the bitter taste, who is Sweetness and altogether desire.

So while our own efforts to make the best of a spoiled gift can only ever rise to the level of consolation, we are given the hope of redemption through the one who makes bitter vinegar into sweet wine again. When that hoped-for moment comes, surely there will be servers there to make our joy richer and to enable our revelling. Let’s not ignore them in the here and now.