I

In a 2012 New York Times essay, Paul Elie laments the absence of compelling portraiture of religious belief in American fiction. Christianity in particular, he argues, gets treated in fiction as “something between a dead language and a hangover.” Elie’s dispirited essay concludes with a wish: “You hope to find the writer who can dramatize belief the way it feels in your experience, at once a fact on the ground and a sponsor of the uncanny, an account of our predicament that still and all has the old power to persuade. You look for a story or a novel where the writer puts it all together.”

One reason putting it all together is so hard to do is that the writer who has actual religious beliefs can’t use fiction to shore up those beliefs or simply confess them. The novel isn’t a sermon or a hymn. Even a novel as filled with love and religious life as Marilynne Robinson’s Gilead (2004) is a portrait of generational tension as well as a kind of wondrous benediction in the face of that tension. To read or write literary fiction as a believer is to put belief at risk, to submit it to pressures it may or may not withstand. Without that risk, fiction becomes allegory, or maybe honest sentiment—comfort food—but not what Elie called for, an account of our predicament.

The most convincing stretch of contemporary fiction that dramatizes belief, for me, is a portion of the unfinished novel The Pale King (2011) by David Foster Wallace. In these pages (originally published separately as the story “Good People”), Wallace presents a young believer who is trapped inside a dilemma that calls for a maturity he just doesn’t have. He wants to do the right, faithful thing, but he confesses himself “two-hearted,” and the story ends with a series of hanging questions rather than a confident resolution. These pages are lyrical, powerful, nuanced, and full of life suffused with religious belief. What they don’t offer is that same faith triumphing. If Wallace has put it all together here, it’s by putting so much pressure on religious belief that we wonder if it’s going to completely come apart. But a faith that comes apart is no longer faith. Fiction that describes lost belief pays tribute to its influence but not to its value.

To read or write literary fiction as a believer is to put belief at risk.

Clearly, literary portraits of religious belief can be done and have been done. Elie’s lament is that most of the compelling attempts are behind us now, not all around us. Eighty-year-old Marilynne Robinson still hosts the high table for anyone trying to embody religious belief in fiction. In the last two decades, instead of easing into retirement, she has offered four volumes of essays (full of theology and cosmology and religious defence), four novels that form a Midwestern saga about the country and the role of belief, and, just this year, a book-length meditation on Genesis. Elie calls Robinson’s Gilead a “tract for the times” while emphasizing that the novel embodies a representative belief from an earlier era, not our own. I suppose a similar qualification would apply to Denis Johnson’s magisterial Vietnam apocalypse, Tree of Smoke (2007), whose title comes from the Old Testament, and whose cast of characters includes a missionary reading Calvin and a Catholic priest accused of gunrunning. The same backward glance describes Ron Hansen’s portrait of winsome nuns swept away on a nineteenth-century shipwreck in Exiles (2008) and the seventies youth group in Jonathan Franzen’s Crossroads (2021).

Religion in some capacity was an anchoring experience in a world that once was. To account for that world required accounting for religious belief in ways that, reading fiction today, we don’t feel we have to. Belief today is an eccentricity, or it’s wrapped in the banners and battle flags of political commitments, or it’s an unthreatening private experience—a nostalgic song—that doesn’t drive the larger narrative of who we are, either as individuals or as a society. Wallace wrote powerfully about religious belief in the present, but the scene lasts for only eight pages. Even that tells you something. And Wallace (does this need to be noted too?) was not even a professing believer.

The challenge is even more complex. I think the extension of Elie’s argument is that we need more than for religious belief to be captured and represented as it’s lived. What we need is for that representation of belief to say something about us and to us—not religious belief as subject matter but religious belief that actually matters. It’s not that we need religion represented in literature so that believers will feel validated and seen. We need belief explored in literature to help churn our collective predicament and to show us important things we might otherwise miss if this older dimension gets ignored. This is what it would mean to put it all together. And Elie’s right: it’s rare to see it done because it’s really hard to do.

Enter Jamie Quatro. Her first book, the short story collection I Want to Show You More (2013), must have been circulating in galley form right as Elie’s essay appeared. Those debut stories offered taut depictions of family and faith, children and illness, the legacies of the South around Lookout Mountain (along with bits of the American Southwest), and persistent, desperate longing. An elderly woman in one story offers a diagnosis of another character that could stand in for many others: “She been deprived of the real. She ain’t never had a touch of the real, all her life.” Quatro puts tremendous pressure on the characters in these stories, including on their faith, and she keeps applying that pressure right up to a two-page story at volume’s end, which includes a final affirmation so quiet and moving it’s as if we’re eavesdropping on an absolution extended (at last) to all the book’s characters.

Quatro’s second book, the novel Fire Sermon (2018), picked up these same themes with even more fervour. Where her short stories explored temptation, her novel succumbs to it, tracking an affair between two married writers. Stripped of its theology, Fire Sermon would be a common story of an affair and its ambivalent aftermath. But everything in this book is hot-wired with religious struggle. It is on fire with guilt and desire, soul-searching and hesitation, regret and defiance. The anarchy of appetite scorches the narrator’s perceptions, but her spiritual wrestling is earnest and learned. Early in the book, she wonders what exactly she would feel if she woke to find that Christ’s corpse had been discovered (and so not raised from the dead), or that airtight proof had been offered that God did not exist. Struggling to make sense of a relationship that feels both life-giving and impossible, her initial answer is “relief.” Later she decides her response instead is “despair.”

Fire Sermon’s project is, at least in part, to reclaim or redescribe the relationship between eros and agape: eros becomes the condition for longing for God at all. In the process, the novel offers an unexpected interrogation of freedom itself. Filled with a longing that seems more powerful and primal than agency, we crave a freedom that would mean permission to indulge it. But what Fire Sermon decides is that without the limiting rails of law, we’re not free at all. Instead, “we are all addicts.” Does any member of our addled smartphone generation need convincing? Offered the utter freedom we think we want, Quatro writes, “we would sate and sate and sate again,” and “we would gratify our longings until we had nothing left to long for, and the ability to long itself died off.” Hermits have sought deserts and caves to avoid being consumed by these same dilemmas. But what if the solution, Quatro’s narrator wonders, is not denying our appetites or quenching every fire? What if, instead, our prayer might be, “Let me burn, only walk beside me in the flames”?

Up to this point in the book, I’m intrigued but I’m not yet moved, and I’m not sure I’m convinced that the stakes are high enough. And then Quatro does what she did in I Want to Show You More: she releases the building pressure in a conclusion devoid of sentiment but so full of feeling and grace it lands as a benediction. It’s the gentleness of this turn that raises the achievement of her work. A tough love story becomes a book about meaning. The arrival of grace for Quatro is not a rescue or a discovery of a new way of seeing. It is a choice. We don’t have a choice about whether we suffer, but we have a choice to make under the conditions of suffering. We can rail, we can submit, or, in Quatro’s world, if we hold on, we might find ourselves able to summon unexpected, hard-won generosity of insight and feeling. In Fire Sermon, the narrator’s affair has hurt her husband and imperiled her marriage, but they stay together. They hold on. And at the “end of all things,” Quatro writes, with biblical resonance, “when Love comes and asks me what I know, I will point to them, sitting there in the shade. I will say: This man. This woman.” That must be the narrator talking. It feels like the author.

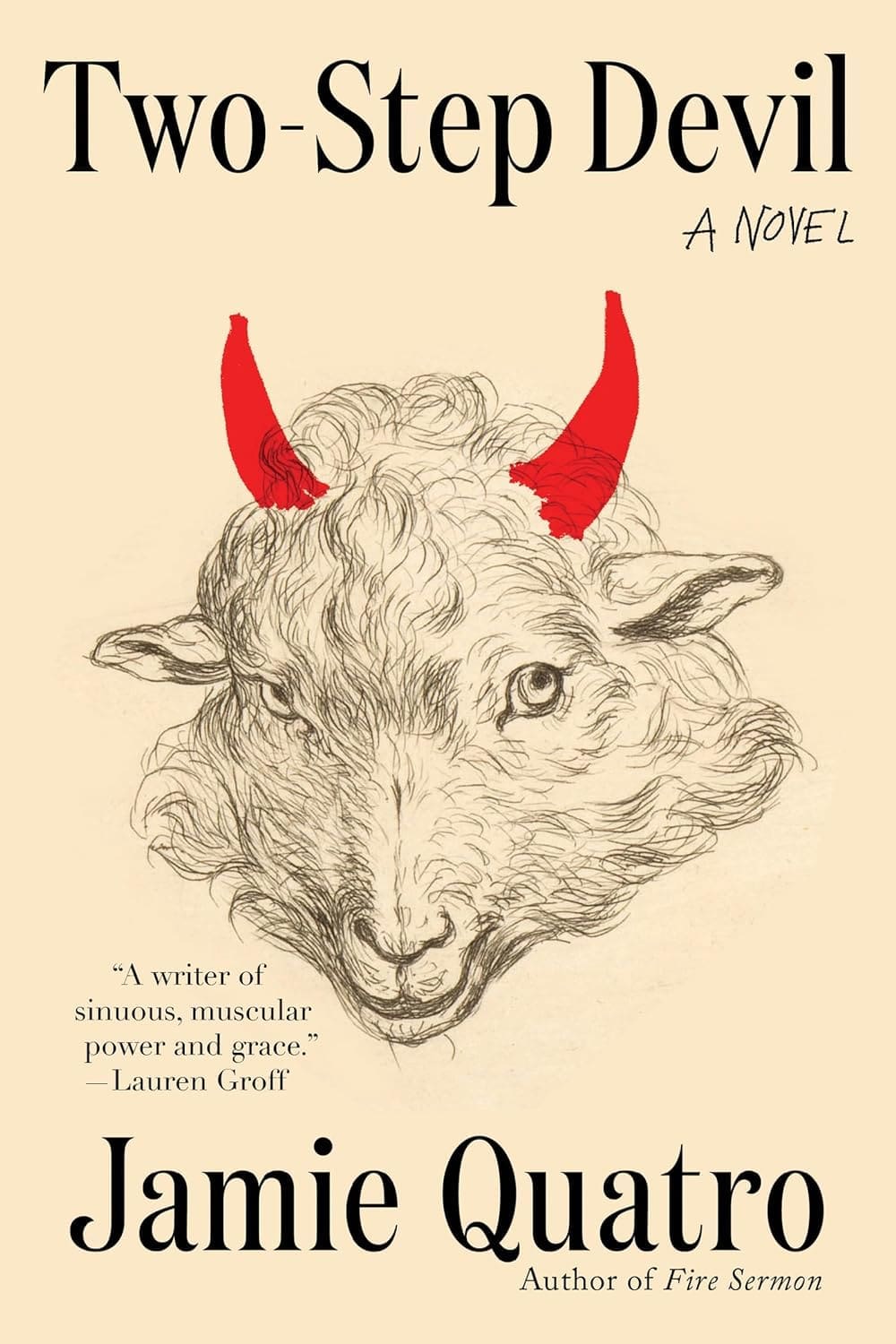

Quatro’s first two books, then, explore in various ways the relationship between faith and desire, and there is nothing straightforward about her treatment of either. Her new novel, Two-Step Devil, stretches her canvas much wider. The themes of family and faith are very much present, and we grow even more familiar with the Lookout Mountain region that has become Quatro’s postage stamp. Her ambition is large, and religious belief still frames that ambition, as the section titles of the book make clear: Prophecy, Song of Songs, Gospel, and Revelation.

Two-Step Devil traces two converging storylines. One involves a man people call the Watchman and the narrator calls the Prophet. In the story’s present, he is old, estranged from his only son, and living alone in a cabin on the Alabama side of Lookout Mountain. People come to his front porch to buy fresh vegetables. Inside, his cabin is a homespun art gallery capturing his biblical visions, including an Ezekiel-inspired assemblage of saw blades forming interlocking wheels. One day, in quest of the final saw blade for his sculpture, in a junkyard beside an abandoned gas station, the Prophet spots an overdressed teenaged girl supervised by a suspicious couple. As their Mercedes pulls away, the girl lifts her arms in the backseat, showing zip-tied wrists. Deciding that he has been sent to rescue her, the Prophet manages to kidnap her away from what he assumes are her kidnappers. The young woman’s name is Michael, as in the archangel who wages war against the devil. Caring for her at his cabin, the Prophet quickly convinces himself that he had been sent to rescue her so that she could take his messages to the powers that be in Washington, DC, including to the president “with the face he trusted” (Obama).

In the long first section in which all this takes place, we get the Prophet’s full backstory: his dropping out of school at the age of nine, his alcoholic father’s early death, his job picking peaches, and an act of violence that sent him to Chattanooga, where he worked in a foundry, got married—and started having visions. His wife bore one son before succumbing to cancer. The son’s musical talent lets him escape his father’s claustrophobic isolation. They have a falling out when he does. Alone and mountain-bound, the Prophet sees visions on five-by-five sheets that drop like movie screens in front of him. There is an innocent comedy to what he reports seeing: floating fried eggs, power plants as beehives, donkeys representing the president. These visions feel delusional, not actually apocalyptic. He is more Don Quixote than he is Ezekiel or John Brown.

The other comic dimension of this prophet’s life is the apparition of the devil that keeps him company in his cabin. This devil is a wiry, cheeky, dancing cowboy, almost a marionette of a two-step devil, sent to taunt the Prophet. In the book’s third section, a one-act, seven-scene play, complete with stage directions, Quatro gives the devil his full due.

But before that theological disputation, the book turns to Michael’s story. Michael is a foster child who is by turns abused, betrayed, drugged, and trafficked. In her first two books, Quatro applied all the pressure she could muster to adults facing adult dilemmas. Here the pressures of a fallen world are piled onto a child. It’s hard to want to see a writer rise to Elie’s challenge when these are the stakes, but Quatro is fearless. The couple in the Mercedes that the Prophet saw that day pimp the young girl to rich customers aboard a derelict riverboat. The drugs are so she’ll float above her trauma; the zip ties are because she tried once to run away. One of her regular customers is a judge—a gatekeeper of justice. Another calls her Angel, darkly playing with her biblical name. Even the Prophet is using Michael. He sees her as his messenger. He gives this teenage girl instructions to travel alone on a bus on his behalf. But Michael is using him too, to get what she wants. Manipulated her whole life, she manipulates escape on her own terms, because she has a secret too.

Quatro is never sentimental. One of the achievements of Two-Step Devil is the way the encounter with the young girl leads the Prophet forward, not entirely out of his delusional visions but away from their dominance and toward a simpler sublime. At first the girl is his messenger, but by the time she leaves and he is confronting his own imminent death, it is Michael herself that matters to him. It’s not quite Don Quixote coming to his senses. But, softly and convincingly, the question that drives him shifts from, What cosmic conflict have I been sent to solve via visions? to, How can I help the one person who needs me? There is no grand speech or dramatic epiphany to mark this change. That’s not Quatro’s style. But the change nonetheless registers with power and beauty. Meanwhile, away from the Prophet, alone on the run, Michael is not out of the woods, not by a long shot.

Before we follow her to her fate, however, we have that strange dialogue between the Prophet and the Two-Step Devil. This stand-alone theological discourse adds ambition to the novel. The devil becomes here more than a figment of the Prophet’s imagination. In this brief play, he is a nimble historical figure, comically misunderstood and misused. “How maligned I have been,” he complains. “How deeply, irrevocably maligned.” In Two-Step’s telling, Jesus has also been misunderstood, and he offers a radically revised gospel to bring him down to size.

Quatro’s theological seriousness is convincing because she embeds it in so much lyricism—and because it is never cheap.

This brief section is important. The book is named for the cowboy devil, after all. Two-Step is not that interesting as a character, but his presence and his voice represent, I think, all the pressures that all the characters (in all of Quatro’s work) buckle beneath. I’m tempted to borrow Lorca’s term and call what he enacts Southern duende—a struggle with a force so real it seems embodied. This devil accuses the human race, mocking all of us for our faulty attempts to “curate the instincts,” to steer and control the things driving us inside, even as we pitifully long for immortality. We are “fleshsacks,” Two-Step says, and while Quatro registers the force of the taunt, she doesn’t deny it. We always will eat that forbidden fruit. We always will hurt even people we love. Look at us floundering around, Quatro’s three books agree. But to quote the poignant ending of I Want to Show You More, something worthy comes of all of this regardless: “I was thinking of Eve and her apple,” that story’s narrator says, “or whatever kind of fruit it was; how she was driven by delight to share the taste with the one she loved, and it ruined them both, but God, knowing this in advance, loved them anyhow.” How beautifully that line moves from the mature assessment of “ruin” to the innocent affirmation of the child’s “anyhow.” Quatro’s theological seriousness is convincing because she embeds it in so much lyricism—and because it is never cheap.

Another part of the ambition of Two-Step Devil involves politics. Here, this powerful book falters. The Prophet’s messages are intended for America (with an exclamation point added). The country, he declares, suffers from hubris, assuming that God blesses whatever it chooses to do because it is his chosen nation. It is arrogant and indulgent, and the Prophet has a warning of a massive heavenly army coming down to deal with all the evil on the planet. It’s not hard to agree that we could use some national humility, but his prophecies sound less like the messages of a third-grade-dropout, backwoods prophet and more like the speech-writing of a political pundit. Here is one example:

Doctors made a fortune to keep the human machine running. And here they were, at the U.S. Pipe and Wheland Foundry, keeping the machine called America running and making next to nothing doing it. Workers pouring the backbone and limbs, welders shaping the skeleton, sealing together the bones of a nation. And who were the doctors and lawyers, the politicians and bankers? The soft tissue sitting overtop. Flesh thinking it was independent of the bones underneath, detaching itself and starting to dry up. And the rotting lips kept making speeches at airports. Madness. America was consuming itself. A snake with its tail in its mouth.

Maybe Flannery O’Connor has infected me to think Southern prophets should be a little more bizarre. It’s hard not to think of The Violent Bear It Away (1960), which also features an older Southerner who considers himself a prophet and who kidnaps a young person in the name of rescue, yet who does not take it upon himself to diagnose, say, the Cold War. In these political stretches, Quatro’s Prophet, to me, speaks with a borrowed voice. In extending the book’s range to address the country at large and not just private life, to tackle, in Elie’s language, something of our collective predicament, Quatro loses the particularity that makes her story compelling. What happens to Michael is as big a canvas as this novel needs. Her plight suggests more about the country than any prophet’s pronouncements could.

And so to a remarkable, uncertain, heartbreaking ending, which enacts and asserts a hard-won grace. Quatro gives us multiple versions of what might happen to Michael, and she summons Two-Step to take us (and maybe the author too) where we might hesitate to go: “Now the difficult part,” this devil begins. “The girl at the bus station. The old man in the woods. You fleshsacks will want to look away. You must bear witness.” In all the accounts of what happens to Michael, it’s Two-Step’s reaction we receive. In one complicated scenario, he scolds the human race for its inability to deal with the most obvious fact about the world, that it is marked wherever we turn by paradox. “And this is the complication for you fleshsacks, isn’t it?” he says. “You cannot stand for the horrific and the beautiful to touch, cannot fathom a system in which one person benefits from the suffering of another. But so it is. So Creator has ordained. What a pathetic state he’s left you in.” Then, in another scenario, closing the arc of the novel with absolution in a way that has become Quatro’s signature, it’s Two-Step who offers tough, tendentious words of grace:

So much kindness among you fleshsacks, is what I’m saying. You forget this. You polarize, call something evil and forget the goodness the evil engenders. You call something good and forget the evil the good depends on. But the kindness! If you counterbalanced all the kindness with the evils you keep putting before your eyes—your newspapers and TVs, apps and websites—you would not recognize your own planet.

But Quatro isn’t done. She will not let us have the happy ending we might prefer. The words that end this morally difficult, emotionally devastating account of a young foster child sound like an accusation but feel like a plea. “This is a story we all know,” Quatro writes, as we tumble where we hoped the story wouldn’t go. “Don’t you dare call it a crime.” There is something startling in that direct address, something moving in the assertion of collective ownership, collective responsibility. It left me thinking anyway, What are we going to do with ourselves, in the world as Two-Step has described it? How are we going to frame our ongoing story? Or will we care that it continues as ours, as a story we all know? Will we rashly scuttle the resources of centuries of religious stories and religious belief? Will they become bizarre cabin visions? Will they really not help us at all? Or can we pull those resources forward even if our relationship to them is ambivalent and haunted by two-stepping doubt?

Jamie Quatro has made religious belief live because she let religious belief struggle.

The passage through so much irresolvable tension gives Quatro’s final redemptive moves something akin to grace, or forgiveness, or maybe love. It takes courage to risk those final notes of generosity and skill to do so while avoiding sentimentality. Who can continue to be so hard on characters who deserve so much compassion? The religious novelist is tempted to rush to the rescue. The unbelieving novelist has to raise the stakes of tragedy in a universe cool with indifference. Quatro plays both sides, but not to draw a balance or make a compromise. The struggles in which her characters are suspended breed tremendous perception. Grace and generosity emerge like storms or fevers breaking. The characters are almost too beaten to receive them. The reader receives them on their behalf.

This is Quatro’s solution to the problem of portraying faith in literary fiction: relentless pressure shapes a final, but never triumphant, redemptive release. But the pressures must be particular pressures, and the releases particular releases. This is the key, the only key, to writing that assesses us and takes our measure through the lens of religious belief. The fiction writer gives us particularity: God loved this couple anyhow. This man and this woman is her answer to a massive theological conundrum about how our small struggles square with our cosmic understanding. In Two-Step Devil, it’s the devotion of an old man who thinks power plants are beehives to a young woman rushing headlong toward a future we can’t bear to imagine. Against oceanic feelings and collective creeds, literary fiction pitches specific encounter, particular hope, embodied grace. In three books that feel both fearless and forgiving, Jamie Quatro has made religious belief live because she let religious belief struggle. In doing so, she put it all together.