W

What am I looking for? An out of date announcement of my own death? —Stephen Maturin via Patrick O’Brien

I see it most clearly the morning after a late night, or at the end of a long and tiresome day. I straighten from the bow I take when I wash my face, I take a moment to let the cold water drip from my beard, I open my eyes to look into the mirror, and I see it: death.

It’s not fully fledged; I am not dead yet. But I will be soon.

I see death in my face: in the raccoon rings under my eyes; in the cracks that spread out from the corner of my eyes like clay drying in the July sun; in the frosty stubble mixed with the blond on my chin. I see death every time I look in the mirror and see that the man reflected there looks like my father.

I look more and more like my father these days. And my dad looks like his father, my grandfather. My grandfather, whom I loved, is dead. My father is getting older and, as much as I don’t want to admit it, he is closer to his day of death than his birth. He is a grandfather, and I am a father, and that means that he has a permanent lead on me, and I on my children, toward the finish line in the race of life. Barring the ever near and present catastrophe, he will cross it before me, and I will cross it before my children.

Is it impertinent to think about your parents—or yourself—this way? Or a sin—the breaking of the fifth commandment incurred by projecting death onto your parents while they are still living? Or a different sin, a type of suicidal thought experiment?

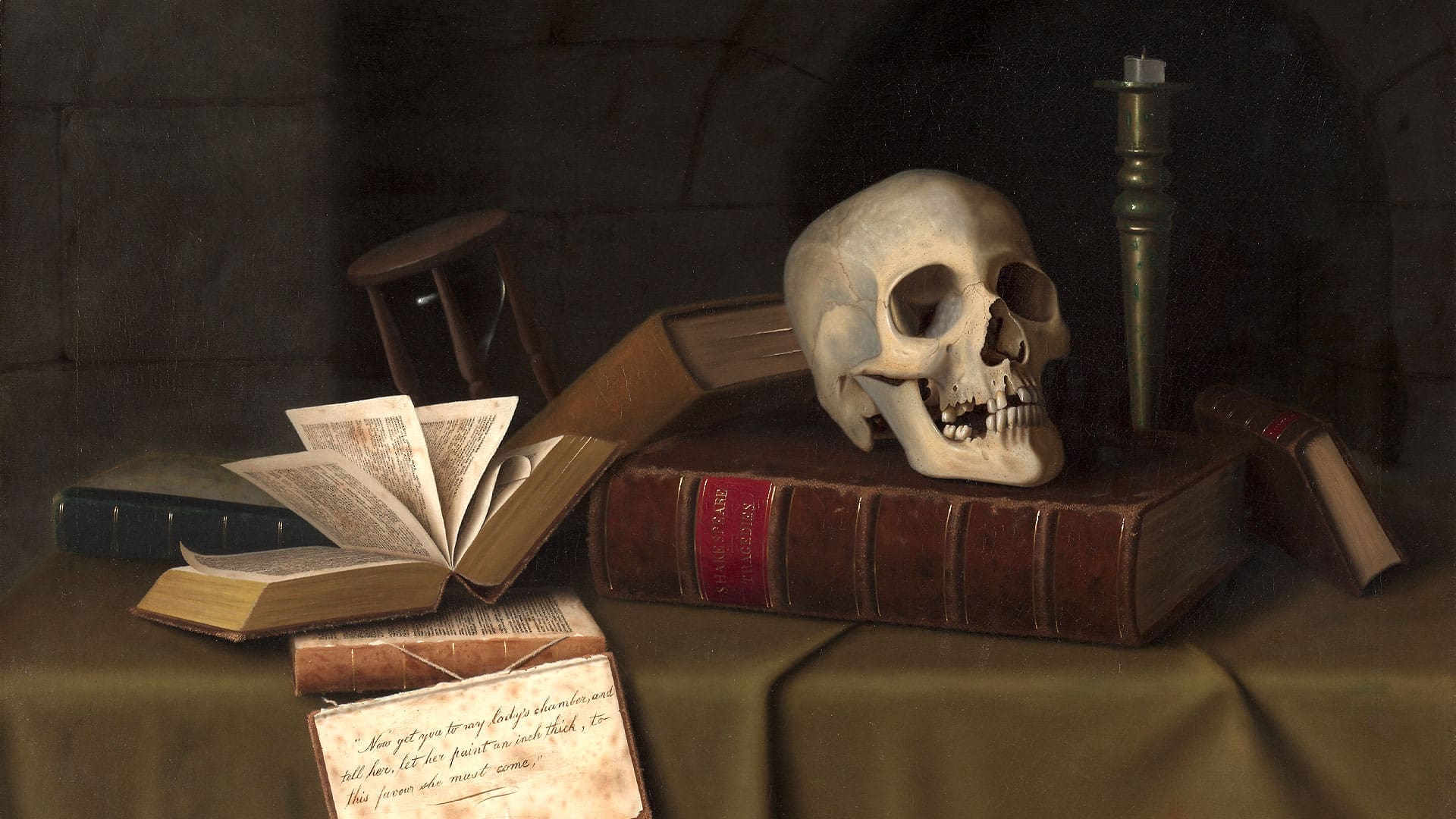

It can be. Contemplating death can be a type of mental flirtation with despair, or a dance with sorrow at having to do the good works that are still required of you. But it shouldn’t be.

The command to honour your father and your mother serves as a divine memento mori. It necessitates looking backward. You must honour your mother and father who came before you, and who created you. And they must honour theirs who did the same, and they theirs, and theirs, all the way back to our first mother and father, and then, the terminus of the trip back (or the origin), to honour the One who created them. To obey the fifth commandment is to run quickly into death; almost everyone in that line of honour is dead.

The command to honour your father and your mother serves as a divine memento mori.

But, as with any memento mori, this contemplation of death is dreadfully present. That line of people is compressed into you. They produced you and you are alive, now. And you must live and act in the present. The question is, how? How do you live in such a way that can honour that long line of givers of life, even if they themselves are not worthy of honour? How, reaching all the way back, are you to honour the Source of all of that life who most certainly is?

I recall a particular time in my life when I broke this commandment. I don’t even remember the context, but I do remember the unwarranted confidence, arrogance, and the feeling of omnipotence (which is patricide)—that I felt in my heart as I went at my father. I, his son whose heart’s desire was to climb the social ladder, was going after him for his failure to “do more with his life.” The impertinence! I’m ashamed even now to write it, but I was hectoring my own father for not being what I thought he should be. I asked: “What is your goal, Dad?”

“My goal is eternity.” That’s all he said.

I was looking for my father to become someone whose death was worthy of announcements in the papers, of public honours. He was looking, and living, for something very different. I wanted fame and fortune in this country; he desired a better country.

Thus the hinge on which the fifth commandment swings: Honour your father and your mother and you will live long in the land that the Lord your God is giving to you. The necessity of looking back through the line of the dead to the Alpha, brings you to your present, and it promises a future flowing with milk and honey in the eternal presence of the Omega.

And so now, when I look in the mirror after washing my face, I see death. But I don’t fear it. I look, through a glass darkly, forward to tomorrow, which will bring me one day closer to it.