A

Alasdair MacIntyre concludes his groundbreaking, 1981 book After Virtue by playing on the title of Samuel Beckett’s 1953 play Waiting for Godot. We are awaiting, MacIntyre famously (and cheekily) says, not Godot, but another St. Benedict, whose monastic, communal, and formative practices might form a virtuous people who have character amid the moral wreckage and fragmentation of modernity.

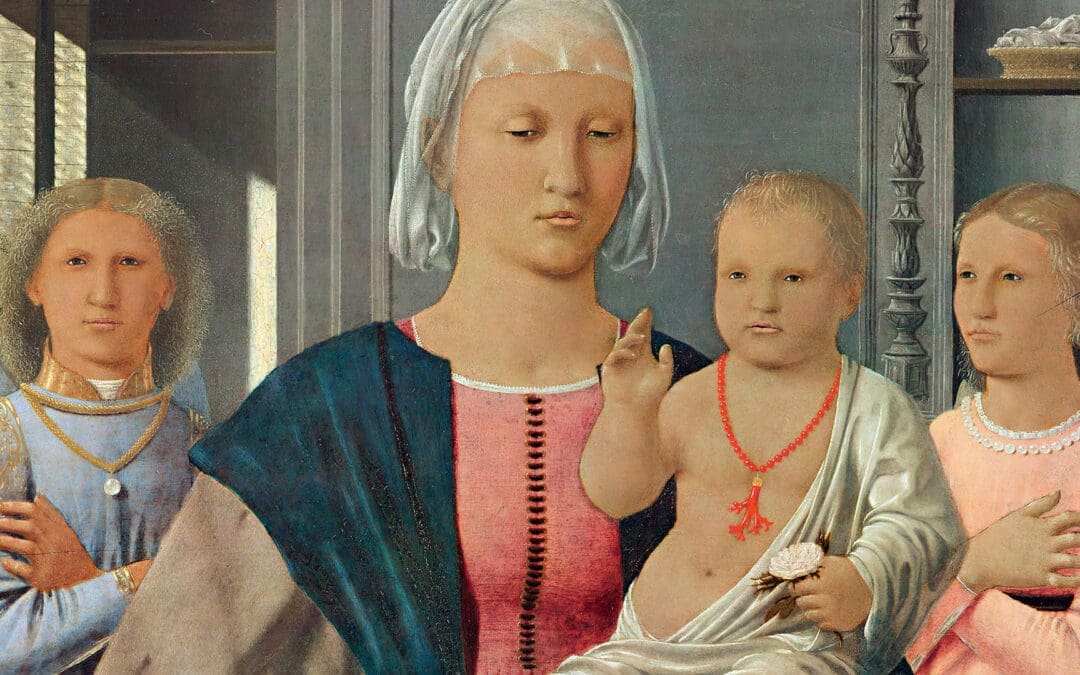

With all due respect to St. Benedict, the ominous shadow of AI and rapid technological transformations of human life have made me long for another saintly figure to arise: an Alyosha. In Fyodor Dostoevsky’s Brothers Karamazov, Ivan launches into a fiery tirade against the plausibility of Christian faith, especially in light of the unfathomable suffering of innocent children. The antiphonal response Dostoevsky provides to Ivan’s arguments is not a discursive but rather a narratival refutation: the elder Zosima and Ivan’s brother Alyosha dramatize a way of being in the world that is determined by participation in the grace of God. Ultimately, mercy abides, while Ivan’s atheistic libertinism and nihilism end in self-destructive madness.

The emergence of digital technology in the last few decades, and artificial-intelligence tools in the last few years, has not resulted in Ivan-like invectives against the Christian faith. But they have fundamentally and rapidly altered countless facets of human life throughout the world, from society-wide changes to our deeply personal notions of the self. Such changes pose a serious challenge to the plausibility of a Christian imagination, especially with respect to what it means to be a human being today.

Of many more examples, at least three trends demonstrate how emerging technology is destabilizing our sense of self and society, to which I respond below, however feebly, with my best attempt at an Alyoshan rebuttal.

First, education at the high school, college, and graduate levels is being undermined and fundamentally distorted by AI, a trend well documented in a recent article in The Intelligencer. Modern education, already focused on mastering skills and techniques needed to enter the post-industrial workforce, has devolved into the art of manipulating AI search engines in fields ranging from the humanities to the hard sciences. Students are becoming more and more reliant on AI to write entire essays or at least generate the thesis statement and supporting points, which students then lightly flesh out. Such practices vacate the process of critical thinking and synthesizing knowledge. As one ethics professor in the article notes, “Massive numbers of students are going to emerge from university with degrees, and into the workforce, who are essentially illiterate. . . . Both in the literal sense and in the sense of being historically illiterate and having no knowledge of their own culture, much less anyone else’s. . . . It’s short-circuiting the learning process, and it’s happening fast.”

But it’s not just students. Even professors are widely using AI. Perhaps the most perverse way education is corrupting rather than cultivating the life of the mind is that AI is being used not only to produce but also to analyze assignments: “It’s not just the students: multiple AI platforms now offer tools to leave AI-generated feedback on students’ essays. Which raises the possibility that AIs are now evaluating AI-generated papers, reducing the entire academic exercise to a conversation between two robots—or maybe even just one.” Whatever debasement higher education has endured in past decades and centuries, we are hurtling toward its absolute vacuity. In the most literal sense possible, AI is dehumanizing the moral and intellectual formation that should occur in our educational institutions.

Second, with respect to human mortality and finitude, as AI becomes more adept at necromancy, it will continue to destabilize what was a previously unimaginable chasm between the living and the dead. Recently, according to reporting by NPR, AI was used for the first time to provide a witness impact statement in a court of law for a murder victim. I am not insensitive to the grieving family members who produced this AI video; it appears that they did so with the utmost care, unlike the routinely malevolent ways that ultra-realistic “deepfake” videos are often used. Speaking about her motivation, the victim’s sister Stacey Wales said, “He doesn’t get a say. He doesn’t get a chance to speak. . . . We can’t let that happen. We have to give him a voice.” Furthermore, the report says,

The experience made Wales reflect on her own mortality. So one evening, Wales stepped into her closest and recorded a nine-minute-video of herself talking and laughing—just in case her family ever needs clear audio of her voice someday. “It was a weird out-of-body experience to think that way about your own mortality, but you never know when you’re going to not be here,” she said.

Since time immemorial, authors have sought, by setting our words down in writing, to speak not only in and to a particular time and place but even from beyond the grave. But in the emerging epoch of machine learning, if enough worthy content oblations are offered up to the forces of AI, then, like the Witch of Endor summoning the deceased prophet Samuel for Saul, the spectral powers of AI will allow for post-mortem content to be produced that is no longer a predetermined deposit bequeathed to posterity. Our literal voice is no longer circumscribed by our lifetime. So long as an adequate amount of clean audio, video, and photography of ourselves is digitally captured, then even death itself can no longer determine whether we are able to address a court of law; virtually any words can be put into our mouths and enunciated with our utterly singular, distinctive voice. Could I not similarly revive a relationship with a deceased loved one, whom I could see, hear, and in some sense talk with regularly?

Third, writing in the New York Times, Ross Douthat persuasively argues that digital technology in general, and AI in particular, is not merely one more instance in the long history of technological advances that disrupt conventional norms and change civilization, but instead poses a serious existential threat to humanity. Douthat writes, “The age of digital revolution—the time of the internet and the smartphone and the incipient era of artificial intelligence—threatens an especially comprehensive cull. It’s forcing the human race into what evolutionary biologists call a ‘bottleneck’—a period of rapid pressure that threatens cultures, customs and peoples with extinction.” But this threat will remain imperceptible, or even appealing, to many. On this point Douthat is worth quoting at length:

Much of this extinction will seem voluntary. In a normal evolutionary bottleneck, the goal is surviving some immediate physical threat—a plague or famine, an earthquake, flood or meteor strike. The bottleneck of the digital age is different: The new era is killing us softly, by drawing people out of the real and into the virtual, distracting us from the activities that sustain ordinary life, and finally making existence at a human scale seem obsolete. . . . But this substitution nonetheless succeeds and deepens because of the power of distraction. Even when the new forms are inferior to the older ones, they are more addictive, more immediate, easier to access—and they feel lower-risk, as well. Swipe-based online dating is less likely to find you a spouse, but it still feels much easier than flirting or otherwise putting yourself forward in physical reality. Video games may not offer the same kind of bodily experience as sports and games in real life, but the adrenaline spike is always on offer and there are fewer limits on how late and long you can play. The infinite scroll of social media is worse than a good movie, but you can’t look away, and novels are incredibly hard going by comparison with TikTok or Instagram. Pornography is worse than sex, but it gives you a simulacrum of anything you want, whenever you want it, without any negotiation with another human being’s needs.

Despite their virtues, institutions such as the child-bearing family involve such a degree of risk, personal sacrifice, and challenge that many people are finding emotional, interpersonal, and even “hyper-real” alternatives on digital screens: not only are they realistic, but they come to seem more real, their consumers finding them preferable to the reality they imitate. That AI poses an existential threat to humanity is already evident in acute, individual cases reported by the New York Times, as people from a wide variety of backgrounds have been “pulled . . . into a quicksand of delusional thinking.” Rolling Stone similarly notes that people are losing loved ones to AI-fuelled spiritual fantasies. But at a broader, civilizational level, the human experience is being drastically altered as it is mediated by screens and digital technology. Institutions, practices, and traditions that are vital to human flourishing—especially friendship, family, and our relationship to a particular place with its land, animals, and people—already are, and will increasingly continue to become, strained and unrecognizable from their historic forms.

Our increasingly tenuous relationship to our physical, human bodies in the era of cyberspace and AI bears an unsettling and unmistakable resemblance to so-called gnostic heresies.

Everyone today, young or old, is faced with an existential crisis unimaginable in past centuries: whether to exist and know oneself and relate to others in one’s flesh-and-blood body in the specific time and locale of skies, soils, animals, and people with whom one lives and dies—or to find the sources of oneself primarily determined by digital screens, algorithms, and artificial intelligence.

The term “red pill” has taken on a life of its own in the age of internet discourse. It came to describe becoming radicalized into various kinds of extremist ideologies, especially on the far right. But Jonathan Haidt’s 2013 book The Righteous Mind describes the literary origin of this phrase and its significance:

Among the most profound ideas that has arisen around the world and across eras is that the world we experience is an illusion, akin to a dream. Enlightenment is a form of waking up. You find this idea in many religions and philosophies, and it’s also a staple of science fiction, particularly since William Gibson’s 1984 novel Neuromancer. Gibson coined the term cyberspace and described it as a “matrix” that emerges when a billion computers are connected and people get enmeshed in “a consensual hallucination.” The creators of the movie The Matrix developed Gibson’s idea into a gorgeous and frightening visual experience. In one of its most famous scenes, the protagonist, Neo, is given a choice. He can take a red pill, which will disconnect him from the matrix, dissolve the hallucination, and give him command of his actual, physical body (which is lying in a vat of goo). Or he can take a blue pill, forget he was ever given this choice, and his consciousness will return to the rather pleasant hallucination in which nearly all human beings spend their conscious existence. Neo swallows the red pill, and the matrix dissolves around him.

Parallels between contemporary problems and ancient Christian heresies are sometimes overdrawn, or irresponsibly handled. Even so, our increasingly tenuous relationship to our physical, human bodies in the era of cyberspace and AI bears an unsettling and unmistakable resemblance to so-called gnostic heresies. That the eternal Logos would become flesh, let alone be crucified and die, remains a scandal of folly and weakness to the world, yet this is precisely where and how the saving wisdom and power of God are revealed (1 Corinthians 1:18–31). We face a choice: do we choose the gnostic escapism of social media and online pornography, outsourcing our practices of reading, critical thinking, and writing to AI, having algorithms provide us with videos to watch and music to listen to, and fundamentally conceiving of our authentic self with respect to the digital persona we produce and the digital media we consume—or do we take command of our physical bodies with all their frailty and limitations?

I, for my part, am resolved to live with my finite mind and its limitations in my mortal body in the material world that has its being by participation in Christ, who is the heart of reality. I want to defy the forces of evil as privation, the simulacra that seem real but only pull God’s good creation down into a deceptive nothingness. Regardless of our theoretical self-understanding, our functioning theological anthropology must contend to cultivate a humane sense of attentiveness to the physical places where we are embodied. We need red-pill people who live in accordance with the terms Wendell Berry writes of in “This Place That You Belong To”:

Hope then to belong to your place by your own knowledge

of what it is that no other place is, and by

your caring for it as you care for no other place, this

place that you belong to though it is not yours,

for it was from the beginning and will be to the end.

Belong to your place by knowledge of the others who are

your neighbors in it: the old man, sick and poor,

who comes like a heron to fish in the creek,

and the fish in the creek, and the heron who manlike

fishes for the fish in the creek, and the birds who sing

in the trees in the silence of the fisherman

and the heron, and the trees that keep the land

they stand upon as we too must keep it, or die.

What might such belonging look like? Here is where Alyosha can guide us. I offer not an outline or a plan, but a narration of the circumstances in which a life outside the corrosive effects of AI can be lived. One of the tensions inherent to Christian self-testimony is that Jesus commends both doing good works in public, so that others might see them and glorify God, and doing them in secrecy, lest they be done hypocritically, only for the praise of others (see Matthew 5:16; 6:1–18). In this case, I hazard to speak of myself—not, I hope, for praise, but so that others might glorify God. What’s more, if I am going to make an argument about how to live and behave in the world, I must bring my own character—and, when necessary, lack thereof—into the spotlight in order to commend, Alyosha-like, the way of life I seek to live.

Recently, having settled into bed after a very long day, I was summoned by my also weary wife for assistance. To skip many unpleasant details, suffice it to say that our very young child needed a bath, clean sheets, and pajamas; and the entire bathroom and a few other rooms also needed to be cleaned. Not a few tears were shed during what is now a blurry, nocturnal memory; at one point I became frustrated and spoke an unreflective, foolish word to my wife, for which I later apologized. Everyone involved was exhausted by the end of the ordeal. But mercy triumphed. My long-suffering wife forgave me, we both physically and emotionally cared for our child, and we all eventually received the rest and quiet that our bodies and minds need every night.

The following morning, though tired, my children and I went for a walk, as is our custom. We walk nearly every day; we walk without any music, and I bring only my dumbphone. As we walk, we listen either to one another or to birdsong, trying to identify which kinds of creatures are awake with us, singing outside at dawn. Our route is neither the most scenic nor ideal for foot traffic, but it is ours. Overhead, a fresh canvas is laid out each morning, sometimes covered with soft pastels, sometimes with fiery explosions, sometimes with menacing charcoal, but today with sombre violet.

We came this morning to a red bench that we often visit, where I ask my children, “What do you see? What do you hear? What do you notice? What do you observe?” They often identify all kinds of things I am otherwise unaware of. A frequent object of fascination for us to look at is a certain Celtic cross made of stone near a neighbour’s house; it has the same Irish knotwork as the wooden Celtic cross I wear around my neck.

These encounters simply would not have happened apart from habits of attentiveness to a local place, its people, the physical world, and our embodied common life.

When we first moved into this neighbourhood, I spoke a few times with the elderly couple who lived at that house. The husband shared that he was a retired pastor who had lived and served in my hometown for multiple decades; since I am from a smaller city in West Texas, I was not surprised to discover that we had several mutual acquaintances. Recently, however, I had noticed that while I occasionally saw his wife outside, I had not seen him for a very long time, leading me to wonder whether he was still alive.

On this morning, several large branches from a tree lay close to her house. As we were sitting on the bench, she happened to emerge. We waved hello to her, and she responded that she had no one to help her move the branches to the curb where the bulk trash collectors could pick them up. She suggested, while delicately trying not to insult me, that they were probably too heavy for one person to move, and conceded that I couldn’t anyway because I had my children with me.

It might be an overstatement to say that the whole of my life and vocation converged on that moment, but it did seem to combine the many aspects of my identity into a single event of knowing and acting, a moment of subsidiary-focal integration. I am a Christian, first of all, and all Christians are compelled by the love of Christ to care for orphans and widows (James 1:27)—a fact of which I am regularly reminded in my imperfect but nonetheless persistent observation of the Daily Office. What’s more, I am a deacon in the Anglican Church of North America, and at my ordination my bishop laid on me the office particular to the diaconate: “to encourage and equip the household of God to care for the stranger, to embrace the poor and helpless, and to seek them out, so that they may be relieved.” I am also a father, and, what with my children watching my every move to see how I would react, the pedagogical potential of this moment was not lost on me. And I am, last of all, a man who has pumped a lot of iron. Whether done vainly or honourably (or, more likely, some Augustinian mixture of the two), I had cultivated the physical strength for such a time as this.

So, with my children looking on, I moved the broken branches. They were not just sticks or brush, but thick, heavy, solid oak limbs. They were also, I soon learned, infested with fire ants and other insects. It was not easy to extricate, dead-lift, and drag them to the curb. In the end, though, I managed it and later returned to cut them into smaller pieces for collection.

Afterward, standing with my children, I mentioned how much we loved her Celtic cross, and that it was nearly identical to the one I wore. I also mentioned that, if I recalled correctly, her husband had been a pastor in my hometown. She said yes, but also confirmed my intuition that he had passed away a few years ago. I let her know that I was a deacon and gave her my phone number since I live not far away, urging her to contact me when she needed help again; she was grateful and said she would indeed let me know when she needed assistance.

My children and I then prayed for her, asking for the blessing of God’s peace to be upon her, and praising God that through the work of the Holy Spirit we get to participate in the death and resurrection of Jesus Christ. Upon arriving home, we said Morning Prayer, and as we recited the closing articles of the Apostles’ Creed, that “I believe . . . in the resurrection of the body,” I made the sign of the cross over my body.

A few weeks later, my children and I brought our neighbour a tray of pumpkin muffins we had baked and homemade cards we had drawn. She had returned home only a few minutes beforehand from attending a difficult funeral for a young woman. On the walk home my children asked me about death, and I spoke to them in the register of the Burial Rite. It says that “in the midst of life we are in death,” but because of the love of God, through faith in Christ, we have the hope of the resurrection of the body, and even now we are joined with the communion of saints, both in heaven and on earth.

Again, I don’t say any of this to boast or to seek praise but to emphasize that these encounters simply would not have happened apart from habits of attentiveness to a local place, its people, the physical world, and our embodied common life. However much or little difference my children and I make in the life of one widow, I am increasingly aware that my capacities for merciful attentiveness to others emerges from an ecosystem I barely understand. From my wife’s and my caring bodily for our son, to my wife’s small act of forgiveness after I sinned against her, to my children’s noticing our neighbour and seeking to befriend her—these habits of attention are fragile and interconnected. However alluring the escapism of digital technology, our minds and souls are inexorably bound to our bodies. We enter life in the frailty of little human bodies, like my son, and apart from an untimely tragedy along the way, we will end life in the frailty of old age, like my widowed neighbour. The mercy of God in Jesus Christ, which created, upholds, and redeemed the good creation that was devastated by sin, has been hard for humanity to remember throughout all ages of quotidian distractions and arrogant, self-sufficient delusions. But the emerging temptations and idolatries afforded by digital technology are quickly eroding our capacity specifically for humane attentiveness to how mercy upholds our common life. However much we might deceive ourselves to the contrary, if we invariably must live and die in the body, what kind of relationship to reality is worth living and perhaps even dying for?

Though we live in an age hurtling toward a digital elision of reality and illusion—especially with respect to education, mortality, and the existential threat to humanity posed by AI—we need stories and embodied habits that form our imaginations to remember that not only another way of life but another world is both imaginable and realistically possible. Encounters such as the one my children and I experienced straddle a distinction not between cyberspace and embodied reality but rather between time and eternity, the veil between sacramental signs and heavenly and transcendent reality. Such a vision of the good life is worth deliberately cultivating and fighting for. In coming years, it will not be convenient, and probably even be socially uncomfortable, to live and die apart from the self-immiserating conveniences, pleasures, and delusions of AI. But reality is good, and making contact with reality is worth the cost of its pursuit. In doing so we defy the supra-human forces of privation that threaten to hollow out what can and should be our hallowed, common life in the body, which in life and in death is wholly reliant on the mercifulness of others.