In an essay offering a Jewish assessment of Karl Barth’s contribution to “divine command” ethics in his “Talking with Christians: Musings of a Jewish Theologian” (2005), Rabbi David Novak expresses some puzzlement about why Barth was so negative about natural law thinking. He sees Barth as a lot like some prominent Jewish thinkers, teachers who advocate a “retreat into sectarian enclaves, where [people of faith] can live more consistently and continually according to the direct commandments of God.” Novak rejects that kind of approach. And having pointed to what he sees as an important weakness in Barth’s perspective, Novak suggests a remedy that should gladden the hearts of at least some Reformed Christians. Expressing the wish that Barth “had been more of a Calvinist in his treatment of law,” Novak offers, in a footnote, some examples of people whose writings he wishes Barth had read with openness to learning from their views. And at the beginning of his list is “the Dutch Calvinist theologian/statesman Abraham Kuyper.”

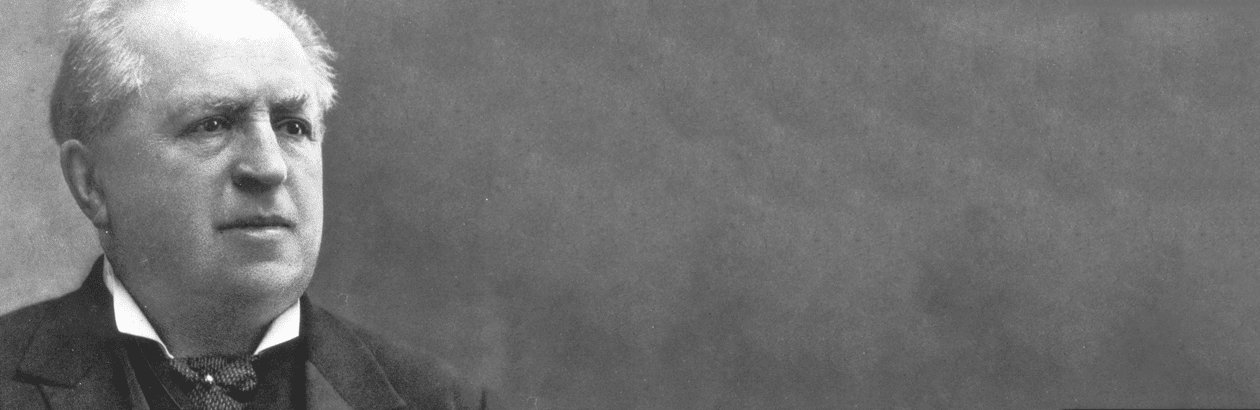

As someone who does his theological scholarship, as the Dutch would say, “in the line of Kuyper,” I take much delight in that counsel to Barth. To be sure, in the same breath in which Novak commends Kuyper’s thought he also observes that Kuyper “was certainly not in Karl Barth’s theological league.” This is a legitimate assessment. When it comes to sheer sustained scholarly theological brilliance, Barth was in a league of his own. There are other theological leagues, however, and if we were to do our ranking with reference to a very broad range of roles and activities, Kuyper does stand out as a giant in the league that we have come to think of as public theology. Much of Kuyper’s theological output was produced on the run. His theological probings were never far removed from his public commitments as the founder of two newspapers, a university, a political party, and a denomination. In addition, he regularly wrote articles for his newspapers, while also leading his party both as a member of the Dutch parliament and, for a few years, as Prime Minister.

Even when Kuyper sat back and engaged in systematic theological reflection, his thoughts were never far removed from his public roles. Two key themes that Kuyper held in tension within his theological system—the radical antithesis between Christian and non-Christian thought on the one hand, and the reality of common grace on the other—played an important role in his political leadership. When Kuyper wanted to rally the Calvinist troops to support an unpopular partisan effort he would preach antithesis, but when the opportunity arose to forge a strategic alliance with another party on a given issue he would remind his followers that God often works mysteriously in the hearts of the unregenerate to restrain their sinful tendencies.

My guess is that Kuyper’s common grace preachments are the kind of thing that led Rabbi Novak to suggest that Karl Barth might have profitably interacted with Kuyper’s thought. And while I take delight in that piece of counsel, I have my doubts whether Karl Barth would actually have received much help from Kuyper on the topic of natural law in particular. Kuyper’s understanding of God’s lawful ordering of the universe was of a very dynamic sort. As Kuyper’s younger colleague Herman Bavinck put the view: “God does not stand outside of nature and is not excluded from it by a hedge of laws but is present in it and sustains it by the word of his power.” Kuyper’s God is ever-present to his creation, a cosmic legislator whose law “lays full claim, not only to the believer (as though less were required from the unbeliever), but to every human being and to all human relationships.”

While these emphases are clearly grounded in a robust theology of creation, they are also linked to a theology of redemption that features the notion, to use the apt phrase that Albert Wolters chose for the title of his book setting forth the Kuyperian perspective, “creation regained.” One of Kuyper’s images for Christ’s redemptive mission is as a kind of cleaning operation. “Verily,” he says, “Christ has swept away the dust with which man’s sinful limitations had covered up this world-order, and has made it glitter again in its original brilliancy.” Kuyper included the full range of cultural reality within the scope of this cleaning operation.

Traffic signals and fire inspections

I discovered Kuyper in the 1960s when I was struggling with fundamental tensions between my evangelical pietism and what I had come to see as the non-negotiable biblical mandate to work actively for justice and peace in the larger human community. Kuyper helped me, more than any other thinker, to see the profound connection between the atoning work of the loving Saviour who is my “only comfort in life and death” and that Saviour’s kingly rule over all spheres of human interaction.

During the 1970s, I attended a gathering of folks who were focusing on “radical discipleship,” and one of the speakers kept describing the United States as given over to “the way of death.” He formulated his case theologically by citing William Stringfellow’s argument, quite popular at the time, that the United States was the present day manifestation of the biblical portrayal of fallen Babylon.

As I listened, I was struck by the gap between this unqualified rhetorical depiction of the American political system as given over to death dealing and my own experience that very week of accompanying our son on his way to school. He had just started kindergarten, and his daily walk to school followed a path through many blocks in the inner city. As I took the journey with him, I was especially aware, as a parent concerned for the safety of our son, of the places where there were traffic lights and stop signs. Approaching the school, I overheard two teachers mention a fire-safety inspection that the city had conducted the day before. Later, as I drove during the noon hour to the campus where I was teaching, I passed another school where a uniformed crossing guard was taking children by the hand to lead them across the street.

These phenomena all struck me as life-promoting services provided by the government, for which I as a parent was deeply grateful. In the light of those services, the unqualified rhetorical depiction of “the American system” as given over to “a way of death” struck me as rooted in, among things, a theological myopia. My uneasiness with that kind of perspective was grounded in what I am presenting here as a very basic Kuyperian impulse.

The late Mennonite theologian John Howard Yoder once captured the impulse quite nicely when, in the course of one of our public Anabaptist-Calvinist debates in the 1970s, someone in the audience asked him if he could put in simple terms what he saw as the basic issue of disagreement between his views and mine. Here is how he answered: on questions of culture, he observed, “Mouw wants to say, ‘Fallen, but created,’ and I want to say, ‘Created, but fallen.'”

That was a helpful way of putting the differences, including the element of ambivalence in each case. We Kuyperians do pay considerable attention to fallenness—at least we ought to—but our basic Kuyperian impulse is to look for signs that God has not given up, even in the midst of a fallen world, on restoring the purposes that were at work in God’s initial creating activity.

This calls for Christians, then, to work actively together as agents of this restorative program that encompasses the whole range of cultural involvement. In those circles where Kuyper’s name is still revered, laypeople credit Kuyper’s influence in their understanding of what it means to serve the Lord in the insurance business or journalism, as a state legislator or in the teaching of English literature. Even when these folks may not know much about the technical details of Kuyper’s theological system, they are quick to quote at least some version of his bold manifesto, set forth toward the end of his inaugural address at the founding of the Vrije Universiteit: “There is not a square inch in the whole domain of our human existence over which Christ, who is sovereign over all, does not cry: ‘Mine!'”

Even politics—often depicted by theologians as a purely post-lapsarian remedial response to human rebellion—is grounded for Kuyper in God’s original creating purposes. Even in a sinless social setting some sort of collective decision-making would be necessary for the harmonious ordering of human affairs. In a sinless world where complex activities take place, rules and regulations would have an important function. Even totally benevolent, God-glorifying human beings would have had to decide which side of the road to drive on, and would have had to stipulate when individuals who wanted to practice playing their tubas could do so without unnecessarily disturbing the naptimes of children who live in the same sub-section of the Garden. It is this same kind of ordering/regulating function that also promotes flourishing under present sinful conditions by setting up traffic signals and hiring school crossing guards.

Families are families; churches are churches

Things get especially interesting in Kuyper when he discusses what it is that God actually wants to be ordered by government, a subject that Kuyper develops at length in setting forth his theory of “sphere sovereignty.” This theory has much to offer to contemporary discussions of civil society, but not without some serious reworking in the light of present-day conditions.

Foundational to the requisite re-working is, as I see it, the preservation of two key Kuyperian themes. One is Kuyper’s insistence that God has programmed creation to display a marvelously complex diversity, including a complex array of spheres of human interaction. The other is the necessity, especially under sinful conditions, that we be diligent in keeping clear about the differences among these diverse cultural spheres.

Multiformity—a favorite term of Kuyper’s—was in his view necessary for created life to flourish in a “fresh and vigorous” manner. Referring to the biblical account of creation, Kuyper noted that the Lord willed “[t]hat all life should multiply ‘after its kind.'” That the Genesis writer employed this phrase specifically with reference to animal life did not deter Kuyper from making a more general application. “Every domain of nature,” he says, displays an “infinite diversity, an inexhaustible profusion of variations.” And this many-ness also rules the world of humanity, which “undulates and teems” with the same sort of diversity, bestowed upon our collective existence by a generous God who from the riches of his glory distributed gifts, powers, aptitude, and talents to each according to his divine will.”

It is Kuyper’s sense that God loves manyness that also informs his sphere sovereignty doctrine. A healthy culture, Kuyper insists, will be characterized by many-ness, plurality. God built these patterns of associational diversity into the very fabric of creation. Families, schools, and businesses do not exist by the permission of governments or churchly authorities—Kuyper was equally critical of totalitarian states and politically powerful churches. God has ordained the plurality of spheres, and no human power has the right to inhibit their proper functioning.

This leads immediately to the second crucial theme: the importance of keeping clear about the boundaries that define the unique character of each sphere. Consider, for example, two persons who are related in three different ways. She is the young man’s mother. She is also an elder in the church where their family worships. And she is the academic dean at the university where he serves on the faculty. Suppose, however, that he commits a serious crime—using, for example, a university computer for illicit sexual purposes. As his dean she will be required to fire him. As his church elder she might even participate in a decision to excommunicate him. But as his mother she continues to love him as a member of the family. In each case her authority role is a different one, as is the basis for acceptance within each relationship. In the university she judges his fitness to remain a member of the community by some straightforwardly formal standards of performance. In the church, she also enforces certain norms, but here with a pastoral openness to repentance and restoration. In the family, the ties go much deeper—so much so that the bond is not easily broken by either bad performance or unrepentant sin. In short, families are families, churches are churches, and the academy is the academy. Suppose, for example, the young man were to complain to his mother: “How can you fire me from my teaching job? I’m your son!” This would be a clear case of blurring the boundaries of the spheres.

Sphere-repair and worldview nurturing

So far, so good. There is a problem today, however, in following Kuyper too closely in the way he spelled out the practical implications of this theme.

During many visits to mainland China over the past decade, I have discussed with church, seminary, and government leaders some pressing cultural challenges being faced in changing urban communities: especially, a rising divorce rate, new patterns of inter-generational conflict, and an increase in the number of suicides. Much of this seems to be a result of a breakdown of traditional kinship systems because of increasing social mobility and the reconfiguring of urban neighborhoods. The supportive infrastructure provided in the past by stable extended families has been deteriorating.

The Christian community in China would do well to place a special emphasis right now on the biblical image of the church as the family of God, and for the church to take on some of the functions of the family. I must confess that there was a time in my life when I would have resisted such a recommendation on Kuyperian grounds. Churches are churches; they are not families. Each mode of association has its own place in the divine ordering of human life. What God hath put asunder let no human being try to put together!

I think differently these days. In many situations one of the spheres becomes severely weakened. Having identified the missing functions, we must do one of two things. Either we repair that sphere in the light of our understanding of God’s creating intentions, or, when that is not immediately feasible, we look for ways in which some other sphere can compensate for the loss by taking on additional cultural “work.” It is important for the church to provide some infrastructural support for cultural “shrinkage” in the sphere of family life.

In Kuyper’s day Dutch families tended to be associated with rather stable confessional or ideological communities. Thus the “pillarization” pattern of Dutch life in which various worldviewish pillars—Catholic, Reformed, Liberal, Socialist—generated distinctive school systems, labour unions, art guilds, and farming organizations.

Things are very different in our own day. We have been experiencing not just a thinning-out but a kind of slicing-up of worldviews. The leader of an evangelical campus ministry observed to me a few years ago that today’s students think nothing of participating in an evangelical Bible study on Wednesday night and then engaging in New Age meditation group on Thursday night, while spending their daily jogging time listening to a taped reading of The Celestine Prophecy, followed by a yoga session—without any sense that there is anything inappropriate about moving in and out of these very different perspectives on reality.

People change religious affiliations frequently in our culture—thus, the phenomenon that has come to be known as “church shopping.” Families think nothing of moving from a Presbyterian church to, say, a Nazarene congregation—while also sending the occasional contribution to a Baptist TV preacher and enrolling their children in a Christian school sponsored by Pentecostals.

Not only are we experiencing sphere-shrinkage, but also worldview-fragmentation. The necessary remedies, then, will require both sphere-repair and worldview nurturing. These in turn require patient work within civil society, in a variety of spheres, including an address to issues in public policy, a focus on various vocations, specific kinds of marriage and family counselling, and so on. And all of that requires new concerted educational strategies on liberal arts and seminary campuses, as well as in think tanks and para-church ministries. And in churches. Especially in churches.

Be near unto God

In some insightful reflections published in Comment awhile ago, Al Wolters suggested that a neocalvinism that is well equipped for our present situation must be under-girded by a deep spirituality that draws on various spiritual disciplines, including those, for example, from both Ignatian and Pentecostal resources. I agree wholeheartedly.

Kuyper has inspired many of us with his profound insights into the ways in which all of the diverse spheres of cultural life stand directly coram deo, before the face of God. But this is an important time to remind ourselves that he also wrote many meditations about the spiritual life, published under the general title, Nabij God te Zijn, “to be near under God.” We need to work diligently today at making a strong connection between the “every square inch” of cultural engagement and a sense of nearness to God that must necessarily be grounded in the worshipping and nurturing life of the local church. Only then can we hope to form the kinds of congregations that will function, in Ronald Thiemann’s apt phrasing in Constructing Public Theology (1991), as “‘schools of public virtue,’ communities that seek to form the kind of character necessary for public life.”

|

This is a condensed version of the “Abraham Kuyper Prize Lecture,” delivered at Miller Chapel, Princeton Theological Seminary, March 29th 2007.