At Seattle’s Harvard Exit theatre last March, I witnessed a rare and wonderful thing on the big screen—a thoughtful portrayal of devout Christians putting their faith into practice.

I was caught off guard. I’ve developed a serious allergy to “Christian movies.” They usually turn out to be big-screen sermons with very little storytelling imagination and hardly a trace of poetry or visual composition. Moreover, they’re often misguided fairy tales that imply a relationship with Jesus will lead to answered prayers, wishes fulfilled, and oodles of happiness. In my experience, the closer I draw to Christ, the more challenging and often painful life becomes.

But this particular movie wasn’t another church-funded production. To my knowledge, this film wasn’t even marketed to Christian audiences.

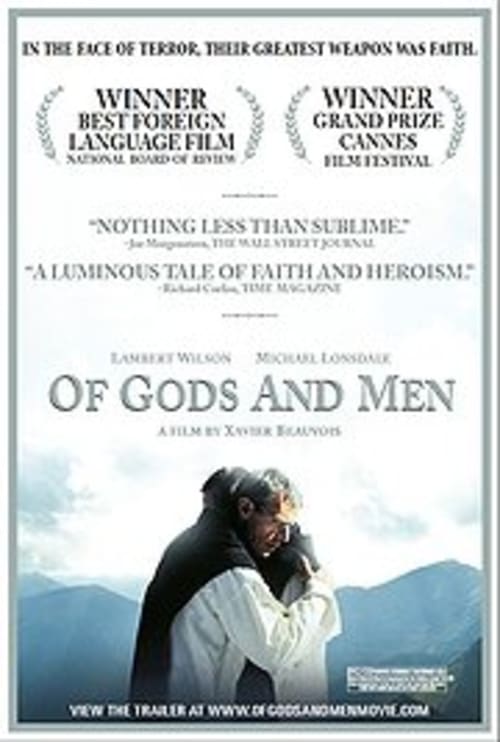

Of Gods and Men is a rare wonder—a film about faith made by artists, not evangelists. It takes Christian faith very seriously, and yet it is crafted with such impressive artistry that it has won international honours: the Grand Prize and the Ecumenical Prize at the 2010 Cannes Film Festival; the Best Film honour at France’s César awards; the Best Foreign Language Film honours from the London Critics Circle and from America’s National Board of Review—just to name a few. (And lo . . . at this writing, it has a 93% positive rating on Rotten Tomatoes!)

So why is it that, almost two years since its debut and a full year after its American release date, the film seems to have gone almost unnoticed in most Christian communities, especially those in which “Christian movies” are celebrated? Why hasn’t it become the new standard for “sacred cinema,” inspiring church-basement screenings across the country? Why hasn’t it caught on with mainstream evangelicals like Courageous, Fireproof, and Facing the Giants?

There are, I suspect, quite a few reasons for this.

No Airbrushing

First of all, Beauvois’s movie sticks close to the details of a historical event that has been well documented. There isn’t a whiff of crowd-pleasing manipulation.

This is the story of how nine Christians banded together to do God’s will under the pressure of violent threats from Muslim extremists. They’re monks—French Trappist monks, to be specific. They served in Tibhirine, a village in the Atlas Mountains of Algeria. In the Monastery of Our Lady of Atlas, they prayed, they sang, they recited liturgy. They also provided health care for their community. They made honey. And they participated in village life, even attending parties for the children of their Muslim neighbours.

As the true story goes, the Tibhirine monks discomforted the Algerian government because their presence aggravated intolerant Muslim extremists who wanted to trample democracy and establish a strict fundamentalist government. After they resisted pressure to leave during the Algerian Civil War, the monks were taken hostage by the Armed Islamic Group (GIA) in order to put pressure on the French government to release prisoners. It all ended in violence.

Who committed the violence? And why? That matter is in much dispute, and the film leaves the question open.

In the wrong hands, it very well could have become an oversimplified showdown—Christians in white hats against Muslims in black hats. We would have been encouraged to cheer for heroes and despise villains. But the film isn’t about naming the culprits who killed them or exploiting the story for sensational drama.

It’s about honouring these men for who they were, what they practiced, and what they meant to the community.

And when the narrative takes compelling turns, the drama comes not because we find these men to be particularly charismatic and impressive, but because we find the call upon them to be a summons that most of us would find almost impossible to answer. As Ken Morefield, a friend and a critic I admire, put it—Of Gods and Men “celebrates their faith because of what it empowers them to do rather than celebrating them for what they did for the faith.”

No Sword-Wielding Soldiers in Sight

In his careful consideration of his subjects, Beauvois shows compassion and respect for all of the characters and cultures involved—the monks, the community they served, even the enemies that the monks remembered in their prayers.

Furthermore, by drawing our attention to the call that these men answered, Beauvois invites us to marvel at a faith that leads men to pray for those who persecute them.

This is a much more poignant picture of the Gospel than those we’ve seen offered by zealous evangelical filmmakers. Jesus invites us to follow his example and to lay down our lives for one another. He does not call us to take up arms and lead a violent revolution, to paint our faces and slay our enemies in the pursuit of vengeance or happiness. The Gospel is not a recipe for winning wars or football championships, or for getting miraculous answers to prayer. It is a matter of meekness, humility, service, and quiet sacrifice. If there is any glory, it goes to God, not to his servants.

That’s why it’s such a rare thing to see the Gospel represented fairly on the screen: It’s the antithesis of engaging entertainment. It just isn’t sexy. The nine men in the centre of this film aren’t soldiers, football players, firemen, or cops. They’re not even particularly muscular. They never handle guns. The only fight they engage is a fight against their own weaknesses.

In mainstream evangelical culture right now, there is a movement to amplify a certain vision of masculinity, and a trend toward repressing and even mocking what is described as “effeminate” Christian behaviour. What the Tibhirine monks do in this film is far from the prevailing conception of “manly” work. They provide medicine and footwear for the local Muslim population. They cook meals. They make honey. They tend to cuts and bruises and even perform surgeries. They offer friendly, personal, humble counsel where it will be heard. They sing.

And their good deeds are not offered as bait to lure people in toward a sales pitch. Their actions speak louder than any sermon.

They’re so humble, I can’t even remember their names.

Okay, I can remember one: Brother Christian. That’s ironic, as he may be the antithesis of what Christian filmmakers are so eager to sell as a model of Christian manliness. He’s not a brawny, assertive, Braveheart Christian who makes brash vows about what he will accomplish in Jesus’s name. Brother Christian (played by Lambert Wilson, who was the Merovingian in the Matrix trilogy) is modest, softspoken, dutiful, fearful, and gentle even toward his enemies.

Yes, gentle.

That’s not a big ticket-seller . . . gentleness.

No Demonization of the Enemy

And the monks in Of Gods and Men are more than just tolerant of their Muslim neighbours. They go beyond mere shows of kindness. They participate in their lives and even read their scriptures—the Quran—and highlight wisdom it contains.

So no, the film is not, as Movieguide called it, “a wake-up call to western civilization” that “clearly contrasts the loving Christian mission and ministry of the monks with the mad cruelty of the Muslims.” Such an interpretation disrespects the love these Christian martyrs demonstrated, and tramples the testimony they hoped to leave behind.

The community that loves and supports the monks, the people who ask them to stand up against the reckless foolishness of the extremists, are, in fact, Muslims. As violent extremists close in, slaughtering Croatian Catholics, one man laments that the killers have “never read the Quran.”

In the film’s conclusion, we hear an appeal from the monks to those who would come after them. It is a powerfully unglamorous appeal. It asks us to see in our own hearts the same sinfulness that we find in our enemies. It asks us to love those who would kill us, even as we love ourselves—just as the dying Christ begged God to forgive the fools and torturers who had nailed him to a cross.

No Vain Aspirations to Martyrdom

Roger Ebert watched this film and concluded that the monks were being prideful by remaining in this danger zone, by risking their lives and skills and not taking them elsewhere where they might do some good.

I am an admirer of Ebert’s work, and I’m grateful for his example of thoughtful criticism, which has inspired me since childhood. But I am confounded by his conclusions here.

Of Gods and Men gives us so many scenes that demonstrate what the monks’ retreat would do to the community that they love, and how it would be a contradiction of their vows. This is the scandalous call of the Gospel—that God sent his own son, who could have gone on healing the sick and raising the dead into old age, and led him instead to the cross at the young age of 33. In submitting to this call, and in overcoming death, Jesus showed us that we need not fear death. His promises empower us to invest all we have, even our lives, for his glory, if that is what love requires.

Why did they stay? Did they selfishly desire to become martyrs? Absolutely not. They desired to show the kind of love that they had been shown.

The villagers described themselves as being like “birds on a branch,” the branch being the monks’ presence. If the branch broke, the villagers would be lost and scatter. The monks chose faithfulness and service. A high-speed chase and a fight against the terrorists might have made for bigger box-office receipts. But the Gospel leads us along a path less popular, and that makes all the difference.

Not a Hit, But a Treasure

In my childhood Sunday School classes, I remember hearing the most dazzling tales of military heroism. I remember drawings of Biblical heroes who could have given Superman and Batman a good fight. These were commanding figures of ferocious violence who kicked ass in God’s name. We cheered for David who knocked down Goliath, not David the poet. We thrilled to the exploits of Joshua, Gideon, and Samson, who seemed like inspiring role models.

It wasn’t until adulthood, when I read the stories carefully for myself, that I saw how the flawed humanity of those holy fools had been censored. Those stories are not about supermen. They’re about what God does with, through, and often in spite of, some truly ridiculous, unstable, untrustworthy characters.

By contrast, Jesus makes “all things new.” He takes the world’s idea of power and transforms it. All signs of physical domination and military force are subverted. Jesus shows the strength of humility, the courage of selflessness, the boldness of restraining anger and violent impulses. He tells Peter to put away his knife, and he heals his own captor’s wounds. He turns the other cheek instead of striking back. He asks us not to demonize sinners, but to turn judgment upon ourselves.

That’s not the stuff of box office success. Nor is it the kind of example that inspires men to sign up on the dotted line in a fever of masculine zeal.

And, to make matters worse, the film isn’t set in America. It was filmed in Morocco, with dialogue in French and Arabic. We’re asked to patiently attend to the voices of foreigners.

So while Of Gods and Men is made with such excellence that it’s won praise from film enthusiasts around the world, it’s never likely to be popular with mainstream audiences, or even with mainstream evangelical Christian moviegoers. It isn’t about inspiring role models. It’s about men who overcome their fears, empty themselves of ego, and serve quietly unto death.

Still, the film will live on in the company of other great films that we might call “buried treasure.” Babette’s Feast is a beautiful picture of the Gospel, but works in a more poetic and parable-like fashion. It is beloved worldwide, and yet remains largely unseen in evangelical circles. Ordet powerfully illustrates the Almighty’s power to reconcile and redeem. Sophie Scholl: The Final Days gave us a powerful portrait of a principled believer several years ago, but it remains relatively unknown. Andrei Rublev, The Flowers of St. Francis, The Passion of Joan of Arc, The Apostle . . .

For all of their strengths, weaknesses, and challenging qualities, these films have one thing in common: They show us that following Christ is costly, unglamorous, heartbreaking, and mysterious. And they ask us to wrestle with difficult questions rather than cheer for appealing heroes. They are, in short, works of art, not propaganda—contemplation, not advertising.

In fact, the most dramatic scene in Of Gods and Men involves a simple dinner, served without a line of dialogue. No showdown. No defiant speeches. No wishes fulfilled by pat-on-the-back miracles. And when the violent finale comes, the monks are not square-jawed champions, but trembling and terrified.

Their strength is made perfect in their weakness, and the only sword they brandish is the sword of the Spirit, which is the Word of God. Quietly, humbly, they follow the call. The glory ahead is for them to realize, not for us to witness.

For us, there is only the question: Would we follow them? And it resonates in the silence that falls with those heavy curtains of snow.