A long time ago in Babylon, Nebuchadnezzar found his sleep disturbed by a dream about a statue. The statue had a head of gold, chest and arms of silver, body and thighs of bronze, legs of iron, and feet of clay. In the dream, the statue was destroyed. None of Nebuchadnezzar’s wise men could interpret this, but Daniel could—not because he was wiser than anyone else, but, he told Nebuchadnezzar, “because God wants you to understand what was in your heart” (Daniel 2:30 NLT, and throughout). Daniel explained that the terrifying statue represented Nebuchadnezzar’s kingdom and the increasingly weak kingdoms that would come after it. Eventually they would be destroyed.

In the United States last year, statues fell too, often pulled down because they represented men and women who were lifted up for veneration but had “feet of clay.” The country was—and still is—divided on what to make of this reckoning, unsure of what is in our hearts. Statues of Abraham Lincoln are now under scrutiny, and many cities are re-evaluating their memorials. (This scrutiny is happening in other parts of the world too: Canadians wrestling with the legacy of residential schools have pulled down or called for the removal of statues of Egerton Ryerson and John A. MacDonald.) Some Christians seem certain of what to make of it all, but others are perplexed. Our sleep is disturbed not by dreams of the future but by memories of the past—and there is no Daniel to offer an easy interpretation of this all.

Frederick Buechner has written several times about a dream he had of a hotel room, one that made him feel perfectly comfortable—at ease and at peace. In the dream he returns to the hotel at a later time and wants to have the room again, but he does not know how to request it. A hotel employee tells him he can certainly have the room; he just has to ask for it by name. And then the employee tells him that “the name of the room is Remember.”

The revelation woke Buechner up with a start. He believed that the dream reflected the power of memory in our lives. Memory can be the key to revisiting the best parts of our past, reassuring us and comforting us in many ways. There are people and places and times we can only visit through memory. When we are unable to access certain memories, we may even feel cut off from ourselves. But there are also memories that we would like to leave behind in a strange hotel and keys to rooms that we cannot seem to discard.

Today, people agree that our shared past is important—but there is significant disagreement about how to interpret and communicate it. Though the term “history” is thrown about in our debates, the objects we most engage with and argue over, like monuments and memorials, are the product of memory. History lives in the realms of complexity and contingency, emphasizing context, testifying to both change and continuity. But while memory builds on fact, it makes more room for fiction and it incorporates more feeling. It is more selective and less comprehensive. Memory is as much about how we see ourselves as it is about what we can say certainly happened.

Public memory rarely sustains a complicated narrative, but rather holds up selected pieces of the past to the present.

Public memory rarely sustains a complicated narrative, but rather holds up selected pieces of the past to the present. We see this in monuments, each a testament to something that someone thought should not be forgotten. They can be eccentric and amusing, like the statue of Dick Whittington’s cat in London, which memorializes the role of the legendary cat in the former mayor’s rise to greatness. They can be sacred spaces for honouring the dead, like the Vietnam Veterans Memorial. They can also be divisive reminders of oppression, like Confederate statues in public spaces. While some monuments are unintentionally hurtful, others purposefully remind us of a painful past for instructive reasons, like the pieces of the Berlin Wall now on display around the world. In their attempts to set memory in stone, all monuments take an event or person from the complex past and isolate them from their context, sending them into the future immobile and inflexible, with nothing but a pedestal to stand on. The same is true of quite a few of the stories we tell ourselves about our past. Just as there are dreams we have for the future, there are dreams we have about the past.

At the moment, our nation cannot seem to agree on how to tell the stories of our shared past or which pieces of that past should be especially remembered. This development is not just a new lack of consensus or the result of current political division, but the consequence of more voices being heard and more opinions being considered relevant to the use of public spaces. How can Christians contribute to these conversations about remembering our past in ways that are biblical and helpful?

Why We Remember

Christians can begin by asking why we remember. The call to remember is not just long-standing, it is biblical. Throughout the Old Testament the Israelites construct altars and name wells as a way of remembering God’s goodness in time and place. After the flood, Noah builds an altar to worship and to commemorate God’s faithfulness. In Genesis 12:7, Abram creates an altar in the place where God appeared to him. In Genesis 16, we learn the name of the well where the angel of the Lord appeared to Hagar. These gathered stones and watering spots were opportunities to remember the places where God’s faithfulness was revealed. And they were remembered for generations: in the Gospel of John, the Samaritan woman was not at just any well, but at the well of Jacob, whom she described as the “father” of her people. The well was part of the long memory of her people.

Practices of memory in the Bible were not just initiated by humans; they were commanded by God himself. After the exodus, God warned his people in Deuteronomy 6:12, “then watch yourself, lest you forget the Lord who brought you from the land of Egypt, out of the house of slavery.” In Deuteronomy 8:2, the people are told they should “remember all the way which the Lord your God has led you in the wilderness these forty years.” With the ten commandments, the Lord reminded his people of his identity through their shared past. He was the one who “brought you out of Egypt, out of the house of slavery” (Exodus 20:2). To forget that would be to forget their relationship to God, the foundation of their identity. The practices of remembrance in the Bible all reminded people of who they had been and who they were in relation to God.

While the Bible emphasizes the importance of the past in understanding ourselves, it does not sanitize that past.

For nations, memory is also linked to identity. For centuries, the English have been urged, “Remember, remember the fifth of November, the gunpowder, treason, and plot.” The rhyme has carried forward the memory of the event, helping to shape national identity. And national identity is fraught with good and bad memory. In the late nineteenth century, French thinker Ernest Renan suggested that forgetting was also part of forming national identity. In order for the horizontal bonds of nationality to exist and last, he suggested that the French had to “forget” to some extent their internal conflicts and divided past, such as the Wars of Religion. What we remember and what we forget is tied to who we think we are and the narratives we have about where we are going. The stories we share over and over become the memory we build our identity on. This is what James Baldwin meant when he wrote, “We carry our history with us. We are our history.”

How We Remember

Christians and nations both need to remember. But the past is no easy thing to navigate. It is full of long shadows, winding passages, and even dead ends. Memory walks through the hallways, choosing some doors to open and others to remain closed. If the Christian tradition affirms the importance of memory, does it offer any guidance for practices of memory? How can the Christian faith tradition help us make sense of, and sensible choices in, collective remembrance that will help our country relate to the past?

One significant lesson from the Bible is that while it emphasizes the importance of the past in understanding ourselves, it does not sanitize that past. Some might assume that because it is full of “heroes of the faith” the Bible must be short on non-heroic moments, but the Bible does not shy away from the limitations of leaders. The tragic flaws of God’s people are recorded alongside their triumphs. Noah built the ark, but his drunkenness was not left out of the narrative. Moses was a murderer and the man chosen to lead God’s people out of Egypt. Israel’s faithfulness and faithlessness are both recorded, time and time again. Though biblical figures are portrayed as more than the sum of their sins, there is no move to whitewash their past.

The Bible does not encourage us to look to the subject of any statue with unmediated reverence. We ought to pause when any statue seems inviolable to us.

When we consider our country’s past, denial of its dark passages is not necessary. The apostle Paul did not shy away from his sense of himself as “chief of sinners” after he had left the name of Saul behind. A faithful narrative of the past can see people as both significant and sinful. In our nation today we are often asked to choose between viewing our country’s past as exclusively good or bad, but Christians are not forced into such a binary. We can contribute to conversations about the individuals and events of our past by emphasizing complexity and finding ways to acknowledge the good and the bad in our public practices of memory.

The Bible suggests that humility can be a solid foundation for understanding ourselves and our nation. It is possible today to see young people wearing shirts saying things like “USA, back-to-back world war champs.” This approach is not only prideful; it fails to accurately reflect the nature of the past. We can look to the words of the time to see this truth. On D-Day, June 6, 1944, FDR called for a day of national prayer in a radio address. He described the soldiers as the “pride of our nation” engaged in “a mighty endeavor, a struggle to preserve our Republic, our religion, and our civilization, and to set free a suffering humanity.” While FDR believed his cause was righteous, he also prayed to God on behalf of our soldiers:

They will need Thy blessings. Their road will be long and hard. For the enemy is strong. He may hurl back our forces. Success may not come with rushing speed, but we shall return again and again; and we know that by Thy grace, and by the righteousness of our cause, our sons will triumph.

This is not the attitude that our stories about the war sometimes suggest. If we see only our own greatness, we cannot do justice even to the victory and the struggle it required. Christians, who remember that “as for man, his days are like grass” (Psalms 103:15), can model an appreciation of our past that does not become prideful—and may be more accurate too.

We need humility not only to fully understand the moments of our past we are still proud of, but also to address the shameful parts of our past. The same United States that liberated concentration camps just a few years earlier refused to allow more Jewish immigration as German Jews sought to leave the Third Reich. The US Army that FDR so fervently prayed for remained segregated under his watch. A sincere look into the past gives us little basis for unalloyed pride. Humility helps us to acknowledge the coexistence of good and bad in our human endeavours.

With regard to statues specifically, while Christians have a calling to be faithful to the past and to practice remembrance, we are not bound in fidelity to all existing expressions of memory. The pharaohs of Egypt built statues of themselves and the pyramids for their tombs, but there was no statue of Moses after the exodus. Roman emperors demanded columns and arches, but Paul did not ask to be preserved in stone. Statues are not essential to the Christian tradition. When we do embrace them, Christians can remember that the Bible encourages us to honour our fellow human beings while warning us against adoration of them. In Acts, Herod Agrippa gave such an excellent speech that he was praised as a god. He accepted that praise, so “an angel of the Lord struck Herod with a sickness, because he accepted the people’s worship instead of giving the glory to God” (Acts 12:23). Most statues in our country are not treated in ways that make us worry about the prohibition of idolatry in Exodus 20:4, but it is clear that the Bible does not encourage us to look to the subject of any statue with unmediated reverence. We ought to pause when any statue seems inviolable to us.

As we advocate for a more honest and complex portrayal of the past, some statues and stories will need changing. In some cases, Christians can agree that, or even lead the charge for, certain statues to fall. Belgium has begun to remove statues of Leopold II, a king who made the Congo his own personal colony and turned the whole of it into a rubber plantation driven by slave labour, a sad story chronicled by Adam Hochschild’s book King Leopold’s Ghost. There is no need for a statue to Leopold. His legacy is entirely negative.

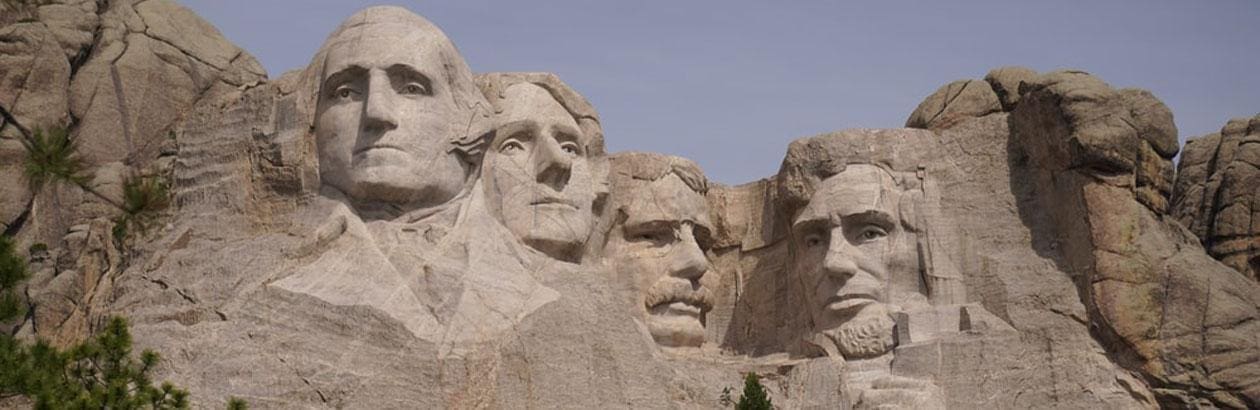

In other cases, we can make statues and stories more honest and more lasting by adding context to correct what may otherwise appear as a false narrative. How should we understand George Washington, who so nobly refused to be president for life and so ignobly owned slaves—who even used dentures made of human teeth, most likely taken from slaves? Such a figure sits at the heart of our origin story as an independent nation, at the intersection of the good and bad narratives we use to understand ourselves. Erasure is not likely to achieve a realistic appraisal of his legacy, and it could never undo his influence. Instead, we can look to Mt. Vernon, which today is not a site of pilgrimage but rather a place of learning that both honours Washington’s tomb and is honest about his life. We should support, and foster, dedicated spaces for wrestling with the complexity of the past.

In all the conversations and debates around our practices of memory, there seems to be a powerful fear that a more honest approach to the past will increase the possibility of division. But truth revealed is not division created. The truth should be handled well—and as long as it is hidden it cannot be handled at all. Our relationships are complicated with nearly everyone immortalized in bronze or studied in school, but thorough, truthful narratives about the past are less likely to create the kind of division that leads to community outrage.

Monuments have been a flashpoint, perhaps in part because they are in physical and not just metaphorical town squares. Public spaces are meant to represent a whole community, yet many of our practices of remembrance speak only for a segment of the population. In contrast, the Bible consistently tells more inclusive, collective narratives, whether in the genealogy of Jesus and all of the included “outsiders” or in something as practical as the memorial in Joshua 4:1-7. After crossing the Jordan, the Lord directed Joshua to find twelve men, one from each of the tribes of Israel, and for each to gather a large stone and “bring them over with you and lay them down in the place where you lodge tonight.” These stones were to be a sign for remembrance:

When your children ask in time to come, “What do those stones mean to you?” then you shall tell them that the waters of the Jordan were cut off before the ark of the covenant of the Lord. When it passed over the Jordan, the waters of the Jordan were cut off. So these stones shall be to the people of Israel a memorial forever.

Each of the tribes joined in the construction of the memorial, and the memorial represented the communal experience of the tribes together. No one tribe or individual had control of the historical narrative or was exclusively represented in the practice of memory. A contemporary example of this kind of approach is Ken Burns’s project UNUM, which approaches US history as “one nation, many stories” and integrates content from a range of platforms to portray the variety within the American experience.

There seems to be a powerful fear that a more honest approach to the past will increase the possibility of division. But truth revealed is not division created.

If more groups shared in the creation of public memory today and saw themselves represented and unified in its expression, fewer monuments would be scheduled for removal. Memorials should be the product of collective community endeavour and engagement. Much of this could involve local history and happen through local organizations. The District Six Museum in South Africa is an example of what is possible when a community is directly engaged in practices of history and memory. As we seek to remember our past, we should think of Walt Whitman’s poem “I Hear America Singing.” Whitman wrote, “I hear America singing, its varied carols I hear,” and then described the songs of carpenters and mechanics and masons and many more, each singing “what belongs to him or her and to none else”—but together it was America singing. The songs of our memory are not solo pieces; they are meant to be sung by choirs.

With all practices of public memory, we should also consider the intended outcomes of memory in the Bible. Some of the most significant practices of memory are the Sabbath, a day to “remember” and be kept holy, and the Eucharist, observed “in remembrance” of Jesus and his sacrifice. Are we cultivating the kind of public memory that produces the effects that come from Sabbath and the Eucharist? Do we cultivate a sense of the past that encourages us to understand ourselves with humility and that emphasizes forces greater than ourselves, such as God’s provision and grace? Or do our practices of memory overemphasize the deeds of men or deny the reality of sin? Can we understand the past in a way that considers and includes everyone, or do we celebrate “good times” for some that came at the expense of bad times for others? Is the way we talk about the past reflective of a table that is open to all?

The debates about statues will wax and wane, but our relationship to the past will continue to be significant. If we believe everything in our past was easier or uncomplicated, or if we knowingly fail to tell the whole truth, we propagate lies that make us ill-equipped to handle the present. We will end up too untethered from reality to create a grounded hope for the future.

Christians have a faith history that values memory and commemoration yet also presents alternative practices and approaches to the ones found so divisive and even inflammatory today. Drawing from this tradition, we can emphasize both complexity and humility as foundational for how humans should view themselves and their achievements. We can encourage collective expression and seek to go beyond an unnuanced celebration of individual human achievement. A Christian approach to the past can help us build shared community in the present.