M

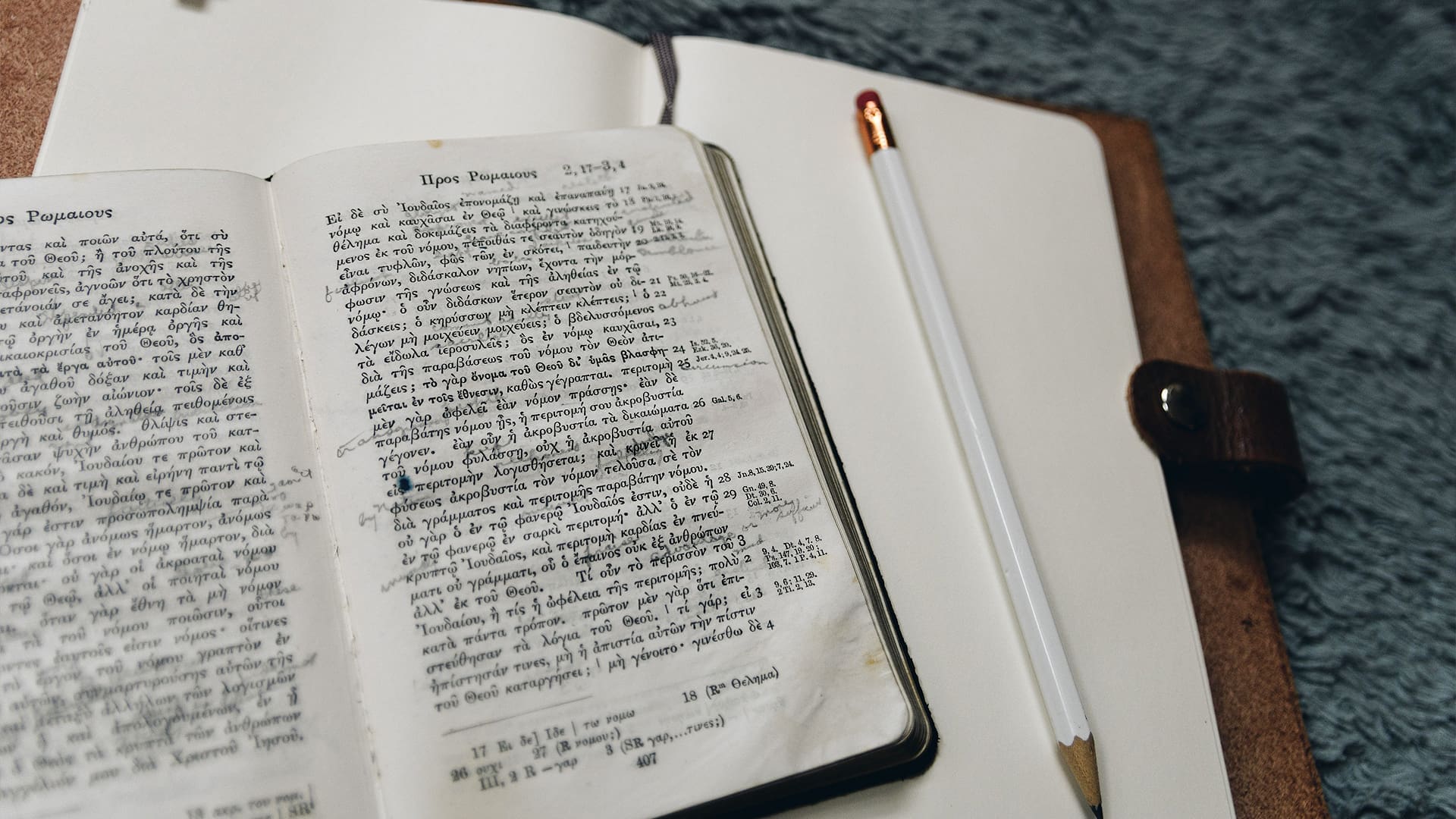

My habit these days, when I first get to my office in the morning, is to set a pot of water to boil for coffee and then to open up a copy of the Greek New Testament. I’m working my way through the Gospel of John, which is famously the easiest Greek in the New Testament to read. It’s still slow going. My Greek is not very good.

I have an audio recording of the Gospel, read in a gorgeous reconstruction of second-century Koine pronunciation, as John himself might have read it. I listen to a few paragraphs and try my best to follow along. Then I pause the recording and go back through the text more slowly, making sure (with the indispensable help of Professor Lidija Novakovic’s handbooks) that I’ve understood most of what I’m reading. Then I read the paragraphs out loud to myself, slowly getting used to the feel of these new sounds. When I’ve finished my first cup of coffee, it’s time to move on to other work. A few pages is usually all I manage.

To many people in our society—even scholars, even Christians—this seems like a useless exercise, or at best an idiosyncratic and archaic hobby, like stamp collecting. Everybody knows that ancient Greek is a dead and dusty language. Everybody knows that the fetishization of Latin and Greek was part of a finally failing project of European self-glorification. And besides, there are already countless beautiful translations of everything I might want to read in Greek, including some really daring and inventive renditions of the New Testament like those of Reynolds Price, David Bentley Hart, or Sarah Ruden. I can’t improve on those. Better to leave the study of Greek to the specialists, surely.

Yet I persist, and I persist in thinking there’s a reason for persisting. More of us ought to study Greek, and it’s not as Sisyphean a task as we’ve been taught to think it is.

In Breaking Bread with the Dead (reviewed in Comment last year), Alan Jacobs has made about as compelling a case as could be made, I suspect, for the importance of reading old books. He argues that reading old books is a way—not the only way, certainly, but an accessible and effective way—of bringing ourselves into conversation with people very different from us. It is a way of increasing what he calls our “temporal bandwidth,” a way of expanding our sense of the Now beyond the often totalizing frames and demands of the present moment. By spending time with people of other times and places, people who see through different prisms and attend to different loves, people whose humanity we recognize yet who exercise that humanity in ways we don’t expect, we become more capable of noticing the peculiar contours and limits of our own experiences. “Reading old books is an education in reckoning with otherness,” he says.

Christians are lucky, if Jacobs is right, to be bound to a whole library of old books. Regular encounters with these old books are part of the rhythm of our common life. These books display a rich variety of perspectives and are written in a rich variety of styles. Surely, then, Christians must be people of impressive temporal bandwidth, unusually capable of reckoning with otherness and unusually capable of standing apart from the passions of the news cycle.

But no, clearly, we aren’t. There’s a decent case to be made that Christians have less temporal bandwidth than their non-Christian compatriots, though there’s no real point in scoring a race to the bottom. That’s because, as Jacobs says, building temporal bandwidth is a matter not just of reading old books but of reading them in the right way. There’s a double risk we have to avoid: we must not read old books assuming that the people who wrote them are totally different from us, and we must not read them assuming that they are just the same as us. It is the work of navigating the tension between likeness and unlikeness that stretches our sense of self, that increases what Jacobs calls our personal density. We have to struggle with an old book, treating it not just as an artifact of a bygone era and not just as a tool to be put to our own present purposes but as a neighbour engaging us in conversation.

Many Christians find it difficult to really reckon with the otherness of the Bible. I see it all the time in the classroom. (I’m an ethicist, not a biblical scholar, but of course you can’t teach Christian ethics without also teaching the Bible.) The most studious and devoted Christians tend to be the least willing to be confused or surprised or (God forbid) angered by the text; they already know what it has to say, and what it has to say clearly and unqualifiedly aligns with the cultural and political mores of their home church. My non-Christian students, on the other hand, tend either to be impressed only by the Bible’s sometimes severe weirdness or to assume in advance that these old books are simply irrelevant to them, whether because they’re “religious” or just because they’re old. It is hard, hard work to get my students—to get myself—to hear these authors speak in their own voices. They are too familiar, or they are too strange.

Admittedly, the Bible is a special sort of old book. Jacobs explicitly excludes the sacred books of the Abrahamic traditions from his discussion, since part of what makes those books sacred, he thinks, is their power to “speak more or less directly across the centuries.” It is certainly true that Jews and Christians and Muslims understand their books to communicate something far more than the ideas of a long-dead correspondent. But whatever else the Bible is, it is also a collection of old books. To read it otherwise is to misread it. To read it otherwise is to give up the great gift of having neighbours, even friends, who lived in the ancient Levant.

Many Christians find it difficult to really reckon with the otherness of the Bible.

It might feel like I’m fighting a battle that’s already over. Even if it’s true that a lot of Christians fail to reckon with the historical distance between themselves and the Bible, it’s also true that historical criticism remains the dominant mode of biblical interpretation in most colleges and seminaries. Students are taught that the definitive meaning of the text is what its author intended it to say and that we can establish that meaning only by carefully reconstructing “the world behind the text”—the established genres of writing, the social and political dynamics that prompted its composition, the connotations of particular words, and so on. They are taught that they cannot properly read the Bible without being amateur historians. They are sometimes even taught to sneer at the interpretations of those who don’t know its historical background.

Dale Martin (who is, by the way, a historical critic himself) has argued in Pedagogy of the Bible that this way of teaching biblical hermeneutics is a mistake, and I agree with him. We ought to admit up front that the text can be read in more than one way and that the reconstructed historical meaning is not the only true meaning or even the measure of other true meanings. Most readers of the Bible before the eighteenth century—including readers like Jesus and Matthew and Paul—were relatively uninterested in questions of historical context. Their interpretations were often much more imaginative, more flexible, more alive than contemporary scholarly interpretations are. That’s not because those readers were naive or irresponsible exegetes; it’s because they thought differently about “how the Bible means,” as my teacher John Cavadini used to put it. These texts, they thought, are capable of not only literal but also spiritual senses, senses not constrained to what their authors had in mind while they were writing them.

There are of course theological reasons for teaching students to attend to the spiritual senses of the Bible. Again, the Bible is a special sort of old book: this, we say, is the word of God, and we should expect God’s words to be extraordinarily capacious and generative. The Now of God’s words is not reducible to the Now of, say, Paul’s letters to the Corinthians. But Martin’s arguments against enshrining the reconstructed historical sense of the Bible don’t depend on those theological reasons; in fact, they fit just as well with any old book. “Texts don’t mean,” Martin is fond of saying; “people mean with texts.” Good interpretations depend as much on readers and their projects as they do on writers and their projects. Historical criticism belongs to one particular readerly project that may simply be insensitive to or ignorant of other worlds the text might open up. For that reason, Martin thinks we need to be exposing students to a much wider variety of readings of the Bible—historical, allegorical, or otherwise—and, moreover, to critical reflection on the work of interpretation itself. Otherwise, even if we manage to convince them of the Bible’s historical otherness, we will manage it only at the same time that we make the Bible a dead letter.

I’m not learning Greek, then, in order to get closer to the one, true, “original” meaning of the New Testament, stripped of the biases of translators. There is no such meaning. Nor will knowing Greek make my interpretations of the Bible more trustworthy than anyone else’s. But it makes a difference, nonetheless, to hear these writers speak in their own voice, in their own language. Even as I struggle to understand what John is saying in his Gospel, maybe even because I’m struggling to understand what he’s saying, he becomes more human to me.

Even as I struggle to understand what John is saying in his Gospel, maybe even because I’m struggling to understand what he’s saying, he becomes more human to me.

In 1925 Virginia Woolf published a volume of essays called The Common Reader. Although each essay is devoted to some writer or another, she refuses the category of literary criticism. The common reader, she says, is neither a critic nor a scholar. “He reads for his own pleasure rather than to impart knowledge or correct the opinions of others. Above all, he is guided by an instinct to create for himself, out of whatever odds and ends he can come by, some kind of whole—a portrait of a man, a sketch of an age, a theory of the art of writing.” The common reader reads for himself, to find something needful in the moment; “he never ceases, as he reads, to run up some rickety and ramshackle fabric which shall give him the temporary satisfaction of looking sufficiently like the real object to allow of affection, laughter, and argument.” Yet as rickety and ramshackle as their fabrics may be, it is these common readers, and not the critics or scholars, who determine “the final distribution of poetical honours.”

We are most of us, at least most of the time, common readers of the Bible. We sit down with it not to reconstruct the politics of first-century Palestine or to consider Paul’s peculiar talent as a writer but to find something we happen personally to need. Affection, laughter, argument.

One of the most striking qualities of Woolf’s essays is how marvellously attuned she is to the humanity of the writers she discusses. She talks about Margaret Cavendish’s talent for designing dresses and about George Eliot’s childhood boredom; she says of Jane Austen that she was “perpendicular, precise, and taciturn.” She comes to know these people by reading their books, and their books take on new significance because she knows them better. She finds her way into their worlds, and they into hers. Reading is a form of communication, and as she says in her essay on Montaigne, “Communication is health; communication is truth; communication is happiness.”

This sort of communication is inescapably more difficult with old books, and more difficult still with old books written in other languages. Woolf devotes a whole essay to the problem, titled “On Not Knowing Greek.” Woolf does know Greek—far better than I ever will—and yet she struggles with the chasm that still lies between her and the ancient authors she loves.

For it is vain and foolish to talk of knowing Greek, since in our ignorance we should be at the bottom of any class of schoolboys, since we do not know how the words sounded, or where precisely we ought to laugh, or how the actors acted, and between this foreign people and ourselves there is not only difference of race and tongue but a tremendous breach of tradition.

It’s impossible, in the end, to really know Greek. She underlines the point again later in the essay: “We can never hope to get the whole fling of a sentence in Greek as we do in English. We cannot hear it, now dissonant, now harmonious, tossing sound from line to line across a page. We cannot pick up infallibly one by one all those minute signals by which a phrase is made to hint, to turn, to live.”

Yet the impossibility of knowing Greek does not keep her from trying to know Greek, from trying to know these particular Greeks, Sappho and Sophocles and Plato. She cannot help herself; she is drawn back to them again and again. As I am, too, with the New Testament. She cannot have done with them, and the translations—moving and provocative though they often are—just aren’t enough. “It is useless, then, to read Greek in translations. Translators can but offer us a vague equivalent; their language is necessarily full of echoes and associations.” Reading these old books in English leaves her stuck in her own English world, in the cold northern winter, she says, instead of the rocky heat of the Mediterranean. So she must read them in Greek, even though she knows she does not know Greek.

I will probably never know Greek very well, but I’m content already to hear the voices of John and Paul and Matthew themselves, at least in a broken way

At the college where I teach, less than a third of our graduating students have spent even one semester studying a language. A much larger proportion of high school students spend a year or two studying a language, but it’s no secret that most come away without being able to carry on even the most basic conversation in the language they’ve supposedly learned. Those of us who grow up in English-speaking homes tend to be very contentedly monolingual.

If we’re going to learn a new language at all, most people think it should be a “useful” one like Spanish or, if you’re ambitious, Mandarin. Even modern Greek might be useful! But ancient Greek is a relic. Ancient Greek is a very hard sell. We’ll go on teaching it in seminaries, since pastors at least have a plausible professional need for the language. But even there, Greek has by and large become optional, and the Greek that is taught is often a painfully truncated “New Testament Greek,” like learning not Spanish but just the Spanish of nineteenth-century Argentinian poets.

Greek also has the reputation of being painfully difficult. That’s partly because it is difficult: you have to learn not just to conjugate verbs but also to decline nouns, not just the active and passive but also the middle voice (still murky to professional grammarians), not just singular and plural but also dual noun forms, not just the subjunctive but also the optative mood. And of course you have to learn a new alphabet. It will certainly take an English speaker longer to learn Greek than it will to learn Italian.

But Greek also has that reputation because of the way it’s usually taught. Students memorize endless paradigm charts and long lists of abstract grammatical concepts (the specific varieties of circumstantial participles, say, or the named uses of the subjunctive mood). They are tested on their ability to apply these concepts to small slices of text or even slices of words, rendering them into English in predetermined ways. Unlike most modern language classes, where you will almost certainly hear and probably even be asked to speak the language on the very first day, students of ancient Greek might study for years without once using the language spontaneously. I studied Greek this way in college—with a very good teacher—without internalizing a single thing. This way of teaching Greek reduces the language to a complicated puzzle.

There are better and more enjoyable ways to learn, and there are more and more resources for getting started on your own. Teachers like Luke Ranieri and Carla Hurt have been recording excellent (and free!) videos based on what are called “comprehensible input” rather than “grammar translation” methods of instruction, which teach you not by forcing you to memorize rules or paradigms but by presenting you with actual, simple Greek that you can understand. It’s increasingly easy to find books that teach this way too: besides the well-established Athenaze books (which I used to get back into the language), there are also more recent simple stories like Jacob Gerber’s Ὁ Κατάσκοπος (The spy) and Seumas Macdonald’s Ἡ Ἑλληνικὴ γλῶσσα καθ᾿αὑτὴν φωτιζομένη (The Greek language illuminated by itself—a still-in-progress work modelled on Hans Ørberg’s famous Lingua Latina per se illustrata). There’s even a group of scholars who have been working diligently to digitize a whole library of learner texts, including both simple ancient texts and graded readers from the turn of the twentieth century, like the ones that Virginia Woolf might have used as a student. It doesn’t take long to get to the point where you can stumble through the New Testament.

I’m not especially nostalgic for the days when Greek was taught in primary school. I am much more invested in finding ways for my own daughter to learn Spanish or Mandarin—which have their own troves of old and beautiful books—than I am in finding ways for her to learn “the classics.” But I do wish there were more places for adults to learn Greek, especially Christians who claim to have such close friends who spoke the language. I wish we were less confident than we are that studying ancient Greek (or Hebrew, or Latin, or any other supposedly dead language) is best left to the scholar rather than the common reader; I wish we were less confident that knowing English is enough. I will probably never know Greek very well, but I’m content already to hear the voices of John and Paul and Matthew themselves, at least in a broken way, and to be reminded when I read them that hearing them has never been as easy as it can seem.