Redeemer Presbyterian Church in Manhattan might be famous for its recently retired preacher, Tim Keller; and many Comment readers will know Redeemer as the home base for Kuyperian endeavours like the Center for Faith and Work. But in a recent conversation, Dr. Keller and Comment editor in chief James K.A. Smith discussed how the nitty-gritty work of pastoral care and church discipline is fundamental to the church’s witness in a globalized world. Here’s the first part of that conversation. The rest can be found in Comment‘s upcoming Fall 2017 issue, A Church for the World.

James K.A. Smith: In our Fall 2017 issue we’re considering the church as a crucial aspect of what we call “social architecture.” To use a helpful distinction from Abraham Kuyper, we believe that the church as “institute”—the people of God gathered around Word and sacrament—plays a role in the common good and in the public good. It’s not just the church as an “organism” —the “sent” church—that has a public role to play. That’s why the health of the church is actually important for society. What do you think about that formulation? Is there anything about it that makes you nervous?

Tim Keller: No. There’s a place where Lesslie Newbigin says there’s a name for cells in the body that only reproduce and don’t do anything else for the rest of the body: “cancer.” If the church is an alternate world, if it’s supposed to be what human life would look like under the lordship of Christ, if it’s supposed to be a counterculture, it should be filled with people who are reaching out and who are repairing other people and repairing neighbourhoods and so forth.

It certainly would seem that, automatically, if the church is the church, it helps the world. It has to. But the danger would be saying that the purpose of the church is to serve the world. Actually it’s not; it’s to serve the Lord. But it will serve the world if it’s serving the Lord.

The danger would be saying that the purpose of the church is to serve the world. Actually it’s not; it’s to serve the Lord. But it will serve the world if it’s serving the Lord.

JS: That reminds me of Stanley Hauerwas’s concern about turning the church into a chaplain for the state. You’re saying that if the church is serving the Lord, and if it is forming disciples who are seeking God’s glory, by virtue of our vocation there’s going to be a spillover effect that should contribute to a wider good.

TK: Yeah. There’s a place in Calvin’s Institutes where he says, “You may not think you owe your neighbour anything, but because of the image of God in your neighbour, you do. Because you see God in your neighbour, because your neighbour’s made in the image of God.” He even goes so far, I think, to say, “Don’t look at your neighbour and say, ‘What does my neighbour deserve from me?’ Say, ‘What does God deserve from me?’ and then when you see the image of God in him there he is.”

He says that on the “creation” level, so to speak. At the level of redemption, you have a man, Jesus Christ, who died for you and poured himself out for you while you were an enemy. Your neighbour is probably not even your enemy, he’s just not a Christian. Calvin essentially says you owe your neighbour a great deal. You owe him help; you owe this person the sacrifice of service. You are not neutral.

JS: Do you think the church is shaping disciples who are answering that call?

TK: Well, if you ask a social scientist, they’ll say that in a very general way people who go to church tend to be more charitable, they tend to volunteer more, and so on. Now I don’t want to be too negative, but I think we probably need to come down from such generalizations and see how far we are from what we should be. But actually the social scientists will tell you that there is a sense in which Christianity—and especially churchgoing—tends to make you more public-spirited, more willing to volunteer your time and that sort of thing. I guess the better question is: Are we shaping people with the virtues or the character necessary to reach out and serve people across racial lines and political lines and things like that? We are a long way from where we should be.

JS: Do you see any particular aspects of the church, let’s say in North America today, that we should strategically try to renew for the sake of emboldening and empowering the church as organism to go care for the common good? Do you see any particular weaknesses or failure or opportunities for renewal in the church today?

TK: In Confident Pluralism John Inazu says that we’re not going to be able to get along with such deeply different views of things. There’s no doubt that people have radically different moral frameworks now. How do we have a cohesive society? He talks about certain “aspirations” in this regard: tolerance, humility, respect, and those sorts of things. He actually does a very good job of defining them, I think; better than most.

He would say patience, for example, is reminding yourself that there’s a limit to what you can prove. Sometimes patience is realizing I can’t prove to the person I’m talking to that they’re wrong. And that should make me patient, humble. But he’s afraid to call them virtues, and you know why. It’s probably because the critique of his whole project is that nothing in this culture produces virtues like that. There’s no place where anyone is systematically teaching humility, respect, tolerance, love for people who are very, very different.

When the Amish children were shot to death and the Amish came around and forgave the shooter’s family and the parents of the shooter, everybody said, “That’s incredible, that’s how we ought to be.”

JS: Same at Emmanuel A.M.E. in Charleston, right?

TK: Yes, yes. But in the Pennsylvania case, there was pushback. Three sociologists who wrote a little book called Amish Grace said the problem is that forgiveness is an act of self-renunciation. Our culture now teaches nothing but self-assertion, that you must never roll over, you must always demand your rights, you must always assert yourself. They asked, “In a culture that teaches self-assertion, will we ever be able to forgive and reconcile?” The answer is no.

The reason the Amish could do it, and the reason why the African American church could do it in Charleston, was because those were formative countercultures where people hear every week about a man who died for his enemies. So you sing about that, you think about that, you pray, and so it’s in you. I think that there was a time, I’m old enough to remember a time, in which the idea of self-denial and self-renunciation was more broadly held in the culture. The idea that you sacrifice for other people and you don’t make waves and you don’t always assert yourself was more general, and that’s where you get the idea of tolerance. Outside of the church—maybe synagogues, maybe some other religious institutions—I don’t know where this is going to be produced.

JS: If ideals of sacrifice and self-renunciation used to be more common, how much is that pegged to more people participating in the rites of confession and assurance of pardon? How many more people were encountering their own sinfulness on a weekly basis? It’s an example of how the very tangible, gospel-centred, God-centric encounter of worship in the practice of confession and hearing God’s mercy spills out into the posture you take every day.

TK: That’s probably right because certainly all Catholics did, and most traditional Protestants did, which is the way God instils the virtues that enable you to forgive. By the way, here we should note that there is a kind of evangelical worship that is lots and lots of energetic music and then a sermon. The normal forms are not there, so you don’t actually have confession or pardon. I would say that more non-traditional evangelical worship is not at that point teaching self-denial.

JS: Especially if the churches are set up primarily to meet your consumer interest in your faith.

TK: Yeah, basically you become a consumer consuming spiritual services.

JS: There’s not much de-centring about that experience at all.

TK: The other thing, of course, is that the Lord’s Supper always requires repentance. There has to be repentance coming to the Lord’s table. So certainly the Eucharist and certainly just the confession of sins, years and years and years of that form you and make you the kind of person who probably can forgive and reconcile. Our culture is fragmenting, in part, because people aren’t being taught that.

JS: Taught in a way that it’s caught.

TK: Earlier we were saying that understanding your neighbour is created in the image of God and Jesus’s dying for his enemies should make us more servant-hearted and more public-spirited, and to some degree it does. The worship service actually creates agents for a pluralist society, in which people who are deeply different get along in peace. That’s one of the greatest needs society has, so the church is supplying those kinds of people.

JS: What if we non-instrumentalize this again for a second. Forget the public-good concern; trust that’s a spillover. As a pastor, and now increasingly a theological educator, where do you most see a need for renewal and intentionality? If you could heal churches, what would you heal in them? What do you wish was stronger, deeper, healthier, more functional in local congregations?

TK: One challenge is pastoral care, primarily because of transience. There is an indication—though it’s hard to prove—that, say, thirty years ago, the average member probably came to church four out of five weeks or five out of six weeks. Now it’s like one out of two. People are travelling more; their attention is divided. Also costs are such that it’s very expensive to have a full-time staff. Frankly, it’s seductive to have a larger church with fewer pastors where people are basically consumers. They’re not really being watched or cared for. There’s pastoral triage, which means that when your life’s falling apart the good churches will be there. They’ll be at the hospital, they’ll be at the funeral parlour, they’ll be in the counselling office. They can do triage. But when it comes to the ordinary kind of positive, proactive pastoral care and intervention where you are actually examining people, only in a nice way—How are you doing? Where are you going? How much do you know about Christianity? Where could you grow?—that’s just not happening at all.

JS: How much is that the weakening of the priesthood of all believers, do you think? Your point makes me think of a line from Klaas Schilder, a minor twentieth-century Dutch theologian who said something like, “Don’t underestimate the significance of the wise ward elder. He is a cultural force.” By attending to families, doing household visits, the elder is a culture-shaping force because he or she is forming people. I wonder how much of what’s missing is not just a lack of pastoral staff but a failure to equip lay elders to do this care.

Several years ago, I was at Whitworth University, and they do a summer program for pastoral professional development—the Whitworth Institute of Ministry. But then alongside it, they do this elder leadership initiative where pastors bring some elders with them and they dive into theology and pastoral resources. I just thought, as go elders, so go the church. What are you seeing in terms of people’s capacity to be elders?

TK: I do think there’s a breakdown. In fact, I get where you’re going and I absolutely agree. The right thing to do is to have a layer of lay leaders; maybe there is an elite group that you can call your elders, but by and large you probably have more like 10 or 15 percent of your people who are mature enough and willing enough and maybe even have the time to be regularly trained by the pastors to do every-member ministry, every-member pastoral care—including evangelism, by the way. Those are the people who bring their friends to church and reach out. But there are also people who are out there just caring for people and then letting you know. They’re your radar system; they let the pastors know.

In a small church where you have maybe eighty people coming to church, then you need about eight or ten of those folks, and you should be meeting with them at least every month. So you’re catechizing them and you’re reading great books together and that makes them feel two things: (1) It makes them feel confident to pry a little bit into people’s lives and have conversations, otherwise they’d be afraid. Most of these folks are afraid to be asked a question they can’t answer. That’s the reason they don’t reach out both in evangelism and in instructing and caring.

So you have to give them (1); but then (2) they have to know that they can get right back to you. If I’m talking to somebody and they ask me a question I can’t answer, I need to be able to get right to you and know that you will get right back to me. So if you have eighty people in your church and you’re a full-time pastor and you have, say, eight or nine people like that and maybe two or three elders as part of that group—you’re going to be fine. Nobody’s going to fall through the cracks, people will lead probably proactively, the minister will visit people and see them, and they’ll also be getting other touches from the church, not just the minister.

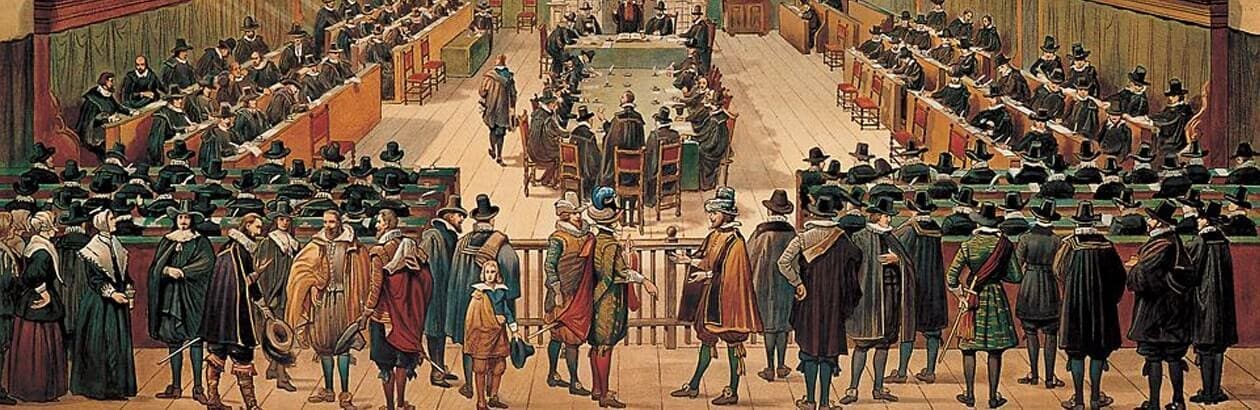

So the priesthood of all believers is absolutely crucial. You know, by the way, in Geneva, what Calvin did—at least I’m pretty sure; you know the experts are going to tell me I’m wrong, but I’m almost sure I remember [laughter]. In Geneva the elders were responsible for wards, and when it looked like there was somebody that needed pastoral exhortation, they were brought before the consistory, which met every Thursday, and it was Calvin and the elders. Evidently, like ninety-five times out of one hundred, there was no real discipline. There was exhortation. So people were exhorted to come to church or to love their wife better and so on.

JS: It’s too bad that our language of church discipline is so narrowly tied to punishment and doesn’t include that exhortation.

TK: My denomination actually does talk about general and specific discipline. “General” discipline is exhortation and oversight. “Specific” discipline is where you actually have an offense and there’s a dispute and now the elders have to figure it out. Some people think only that’s discipline, but actually exhortation is discipline as well.

JS: It embraces the positive sense of discipline we bring to the athlete, right? The athlete is disciplined, the musician is disciplined. What that means is that they give themselves over to rhythms, practices, and accountability that lead to their flourishing and excellence.

TK:And it’s also their halftime talk. It’s the coach, you know, looking you in the eye at halftime and saying, look, it’s up to you guys; you can do it.

Be sure to read the rest of the conversation between Tim Keller and James K.A. Smith in the Fall 2017 issue, A Church for the World.