A prayer 500 million years in the making.

We have ourselves a disagreement. A debate breaks out as our hosts discuss Shadi’s new book, The Problem of Democracy. Shadi argues that we should see democracy as a mere form of governance, a systemic way to resolve ideological conflicts peacefully. Matthew argues that in order for democracy to endure, it must be more than a mere mechanism—it must be a way of life, something we practice, treasure, and even revere. As ideological conflicts threaten to divide countries across the globe, the stakes could not be higher.

Matthew Kaemingk: Welcome to Zealots at the Gate, a podcast of Comment magazine. I’m Matthew Kaemingk.

Shadi Hamid: I’m Shadi Hamid.

Matthew Kaemingk: Together we research politics, religion, and the future of democracy at Fuller Seminary’s Mouw Institute of Faith and Public Life.

Shadi Hamid: We are writing a book together. This podcast represents an informal space where we can talk about how to live with deep difference. Thanks so much for joining us. Make sure to subscribe wherever you listen to podcasts. Please consider leaving us a review. If you want to reach us directly, you can get a hold of us on Twitter with the hashtag #zealotspod, or you can email us at zealots@comment.org, and we do check those regularly, so we would love to hear from you.

So as many of you know, Matt and I are good friends, but perhaps we shouldn’t be or perhaps it’s a little bit unexpected. Matt is Christian; I’m Muslim. Matt is conservative; I’m liberal. Yeah, for the most part. Matt is white; I’m brownish. Matt is a theologian; I’m a political scientist. Matt is from a place of America that I’m not super familiar with, called the rural Northwest, I believe, and I am from a Northeastern urban elite enclave. So our identity markers indicate that we maybe shouldn’t be friends, but we are.

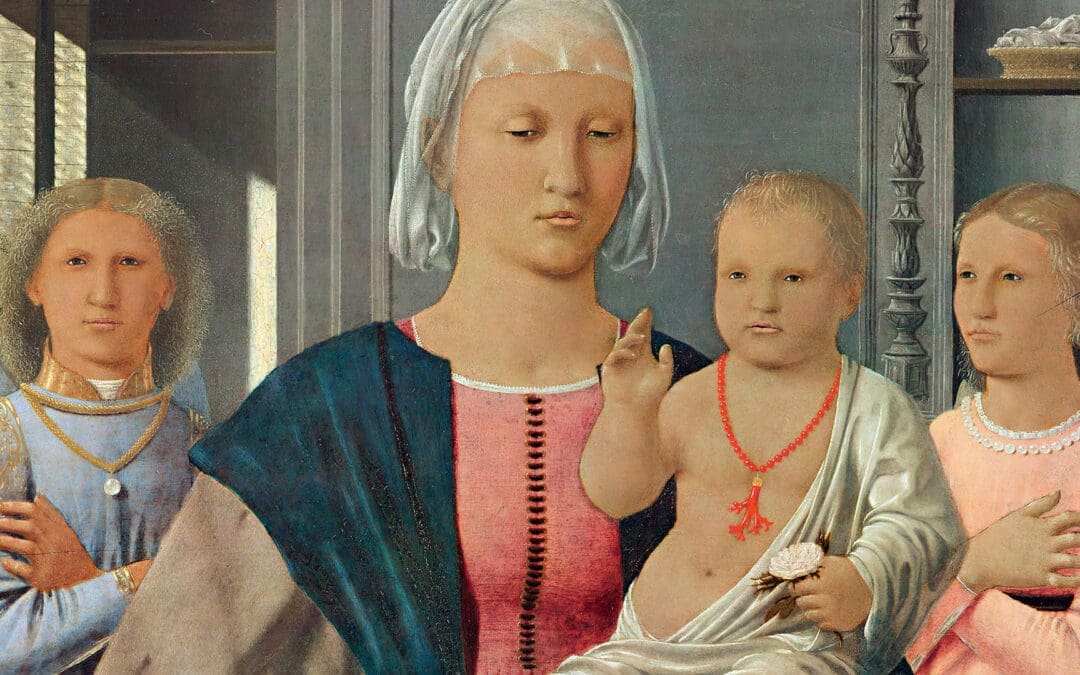

Matthew Kaemingk: Yeah, Shadi. So hey, what we’re going to talk about today is your new book, with a beautiful new cover. So for our listeners who are watching us on YouTube, I have here The Problem of Democracy by Dr. Shadi Hamid. It’s a beautiful cover.

Shadi Hamid: It does look really nice, actually.

Matthew Kaemingk: Doesn’t that look nice? It’s shiny.

Shadi Hamid: Some Swiss minimalist design.

Matthew Kaemingk: Yeah. So we’re going to chat about this book, Shadi, and you have been out there on podcasts and cable news talking about this book, and you’ve been asked a wide range of questions, and what I would love to do is focus specifically on an idea that you talk about in this book, specifically called democratic minimalism, and I want to dig into that and I’ve got some tough questions for you. But before we dig into that very specific question, for those listeners who have not read your book, I’m hoping you could give us sort of a quick overview if that’s even possible, because this is a very rich and thick text on politics, religion in the Middle East. Could you just give our listeners sort of a quick overview of the book?

Shadi Hamid: Well, first of all, thanks, Matt. I’m excited to hear your thoughts, and pushback and criticisms potentially, about some of the book’s key arguments. So the book fundamentally focuses on a key question, which for me really animates so much of my work in writing, really over the past ten to fifteen years, which is, What do we do when democracy produces bad outcomes? And I would put the word bad in sort of scare quotes because part of the issue is we no longer agree on what a bad outcome actually is. What I try to do is propose a resolution to this democratic dilemma of democracy being nice in theory but not so nice in practice, when it results in things that we consider to be personally threatening to ourselves, to our families, to our communities.

I take cases in the Middle East where right-wing religious parties came to power through free elections during the Arab Springs, so here I’m talking of course about Islamist movements and parties like the Muslim Brotherhood, but the argument can be applied more broadly as well. This has become a universal problem, whether it’s Brazil, India, Israel, Italy, Poland, France, Sweden, and of course the US. Obviously, a lot of liberals have asked themselves, “Well, what if someone like Donald Trump wins again?” or Republicans who consider Joe Biden or someone like him to be unacceptable and didn’t accept the election results in 2020. So it’s a long list of examples that we can point to. I won’t say too much more than that. If any of you are interested, we’ll include a link to the book in the show notes and also an excerpt in the Atlantic that captures some of the key arguments and contentions.

At the centre of my vision of how I want us to address these dilemmas is through something that I call democratic minimalism. I want to readjust our expectations. I don’t want democracy to be this big overarching ideological thing that is out of reach. I want to make it something practical and accessible because part of the problem in my view is that we project such a burden on the democratic idea, and it’s a burden that I think it can no longer carry. We expect too much from democracy, and so it disappoints us. So let’s adopt to more minimalist conception of democracy, so that way expectations and reality can be more closely allied. And obviously this is controversial for reasons that I’m sure, Matt, you’ll touch on, but come at me. Yeah, I want to hear your strongest objections, and yeah.

Matthew Kaemingk: I will bring it. I will bring it. But I’m going to leave you on the line just a little bit longer here, and I want to turn specifically to the Middle East for a little bit, and the context within which your ideas are coming, because I think that’s really important to understand. And because I’ve been living in this book for the last three days, I’ve been reading these sort of gripping stories of revolution in Egypt and Syria and Jordan and Morocco and, really, the tragedy of democracy in many ways. It is a very sad story that you tell of hopes lost and repression and violence and hypocrisy as well.

I think at the core for many Americans as they think about democracy in the Middle East . . . and I know for me, as I was coming up as a young political science major, I experienced 9/11 when I was a junior and then the Iraq War as I was a senior or so. Yeah, that was about that sort of order there. So there was a great deal of optimism coming from George W. Bush about promoting democracy in the Middle East, with his chest out: we can do this, we can bring this democracy, and we’re going to make the Middle East sort of safe for democracy. Then a whole lot of mess happens, and it seems to me that in the wake of the Bush presidency, the story you tell is one of Obama and his ambivalence about what to do with the Middle East. He doesn’t share that sort of broad-chested hope for a democratic new day in the Middle East. He also doesn’t want to demonize Muslims and Islam and say Islam is incapable of democracy.

So the story you tell, or at least the way that I take it, is sort of Obama’s ambivalence or his indecision in terms of how much does he believe in democracy in the Middle East and how much is he willing to put on the line to defend democratic movements in Egypt and in Syria and in Jordan—that sort of indecision from America about how much it believes in democracy and is it willing to live with the results of that democracy. That indecision created space for a lot of violence and military coups and difficulty. So I think the story you tell of the Obama presidency and the people that you talk with in his State Department and in the Pentagon, and then the people that you talk with in Egypt and Jordan and others, really share a story that this question of democracy is not academic, but real lives are on the line.

So it’s a real urgent question, which is, what is democracy? What are we willing to defend and what are we willing to spend in terms of defending that democracy? Am I hearing your argument right there? How would you edit what I—

Shadi Hamid: No, that sounds quite good to me. Yeah, we as Americans have been ambivalent for a long time about democracy in other regions, cultures, and of course religions. So one of the problems here is the “problem of Islam.” The problem here in quotation marks that Americans struggle to understand Islam’s role in public life because there is no equivalent to Sharia and the Christian tradition. So then it’s hard to get one’s head around the idea of Islamist parties coming to power who say that they want to implement Sharia. When we hear that as Americans, our shoulders hunch up and we get a little bit, “Oh no, well, that doesn’t sound good,” and it may not be good. A big part of how I view the democratic idea is that it doesn’t have to be good.

Democracy does not guarantee good outcomes. It can lead to people and ideas that we consider bad being in a position of prominence, and I think that we have to come to terms with that. If we do come to terms with that, then we can address some of this ambivalence that has animated US foreign policy. The key example with the George W. Bush administration is that you’re exactly right, Matt, that Bush was a true believer, and for those of you who want to look back at some of Bush’s classic pro-democracy speeches, they are stirring; they are rhetorical wonders. It’s really impressive stuff. Now, you guys might not like it because it’s kind of messianic, and clearly Bush’s Christian conviction plays a role here that he doesn’t just see democracy as something to support but rather something to believe.

In this sense, George W. Bush is really a universalist, and this theme that democracy is accessible to all peoples and cultures, that there is no specificity, there is no group that is outside the scope of the democratic idea—and, you know, credit where it’s do—I find that to be quite appealing. Obviously, there’s the dark side of this messianism as well, but it’s interesting that even though Bush and his top advisors were true believers for the most part, when democracy produced a bad outcome in Palestine . . . So some of you might recall Hamas won the January 2006 elections. It was a big surprise. This isn’t actually apocryphal because Condoleezza Rice does allude to it in her memoirs, but she found out the news when she was on her treadmill. I’m not sure if she was at a gym or she had her own treadmill, but I guess it doesn’t really matter. The point is she almost fell off her treadmill because she was shocked to hear that Hamas had won, and Hamas not only is an Islamist movement, but one that obviously engaged and still does engage in violence against Israel.

So what do we do about that? That is the democratic dilemma. It’s an extreme case, but it illustrates this tension. What do we as Americans do when we want to believe in something, but then it produces something that we are profoundly uncomfortable with? I think that’s a question each and every one of us has to ask ourselves really, and I’ll also just say that . . . yeah.

Matthew Kaemingk: Yeah, and I think right there, I mean, I think what you’re doing right there is you’re putting your finger on a key tension within American identity, which is every American wants to say, “I believe in democracy, I love democracy, and I want to defend democracy.” On the other hand, they want to say, “I want to resist religious extremism and oppression.” So when they see Islamists and Salafists participating in democracy and potentially winning democratic votes, then they have these two identity markers in tension with one another, and you’re sort of pushing on a very uncomfortable reality for American—

Shadi Hamid: Yeah, because I always take some degree of pleasure and highlighting to people that good things don’t necessarily go together. There is this kind of built-in American optimism that if something is good, it will lead to other good things, but we have to be much more aware, and maybe this is a little bit dark, but the more of one good thing that we have, then the more of another bad thing we’ll likely have as well. So I almost see it as the opposite that in sort of God’s cosmic justice, there’s an equilibrium and a balance, and if there was too much . . . if there’s too much good where it’s almost like lopsided, it’s almost like in my mind that God almost has to step in to kind of redress the balance because then things are just sort of out of . . . it’s almost unnatural if too many things are good all at once, and that’s not like a theological . . . yeah.

Matthew Kaemingk: Well, I mean, I think your book is coming out of this sort of post-idealism of the 1990s, the post–Cold War, when democracy is the future, this is the end of history. We’re all sort of moving up in this liberal democratic international order. So Bush kind of in many ways represents the zenith of that hope and belief that democracy won’t let us down; democracy will bring liberty, it will bring rationality, it will bring peace, and if we make the world safe for democracy, people will rationally choose a more western European—

Shadi Hamid: So I’m glad you brought that up. Bush actually was also a believer in what’s called the pothole theory of democracy, where in a press conference—I can’t remember the exact date—he’s asked about Hezbollah, another controversial Islamist group in Lebanon, like what happens if they do well in the elections? He basically says something, “Well, I trust that if people have the right to vote and choose, they’re going to be more concerned about filling in the potholes and improving their local environment, and they’ll move away from militancy or radicalism.” There is this almost naive faith that once you give people freedom, everything will just work itself out. Of course, we know that . . . it’s not even just about Muslim majority context. We’re increasingly seeing that these assumptions are not really warranted anywhere, and we’ve alluded to this in previous episodes, in the election results recently in Sweden and Italy where far-right parties came out on top.

So I think that all of this is just really good fodder. I’ll also just say for me, and this ties it to the question of religion, I think it’s fair to say that it’s not just that I support democracy. I am a believer. So when I use that language sometimes, I have a faith in the democratic idea. I believe in the democratic idea. Some of that is tied to my own religious convictions. My friend and sparring partner Damir Marusic would often bring this up in our conversations, that he would try to understand what was animating this kind of conviction. I felt so strongly about it, and we worked through that a little bit, and I started to realize that a big part of it is my monotheism. It is tied to my belief in God because there is something about authoritarianism that to me is a direct repudiation of God’s will and God’s creation. If human beings are basically controlling the lives of other human beings and not allowing them to express their preferences or vote for their leaders, then that is distorting the human spirit in some fundamental way.

Matthew Kaemingk: Yeah, and the way you say it in the book, I thought, was just so compelling, or of course, throughout the book, you’re a pretty clear political scientist, writing as a political scientist, but you sort of fall into theology every once in a while, and it’s awesome when you do. In one part early on, you make this statement that God made us to be political animals. God invested us with power and the responsibility to use that power wisely. So authoritarian regimes are not just unjust; they are denying that God’s gift to human beings, that human beings have been created to wield political power, and the evil of an authoritarian regime is that it removes that very human element, which is to have some level of power, some level of say over your life.

So your point there is that authoritarian regimes are not simply destabilizing or irresponsible. They’re unjust, and they’re disrespectful of your monotheism, of your belief in God that God alone has that power.

Shadi Hamid: Yeah, I hesitate to use a word that says stark as evil, but I do think there is a kind of base— [laughs]

Matthew Kaemingk: I don’t. [laughs]

Shadi Hamid: There is a kind of base evil to autocracy. This is also why I’m bullish on America. I mean, for all of its faults, America, I believe, is not only politically superior but also morally superior to any autocracy in the world. So if you take, for example, I would say, an increasingly secularized country here in America, we are still morally preferable than any Muslim-majority society that is governed by a dictator because of this kind of fundamental distinction that I raise. Just to reiterate this, I say in the book that if you as a human being, as an individual, if you don’t have access to politics, if you’re not able to participate in the political sphere, if you’re not able to have a say about the things that affect you and your family, in some sense you are not being allowed to be fully yourself. You’re cut down the size. You’re being in some sense forced to be less than God intended you to be.

Matthew Kaemingk: Yeah. Now, for those of our listeners in North America, I know that this fact is very . . . you’re well aware of this, but I think for many North Americans, we are not when it comes to the Middle East. One time I was giving a talk about extending . . . I was giving a lecture to a group of Christians on why they should extend rights and dignity to Muslims in America, and I got the same question I get quite often from a young Christian man, which was essentially, “Why should we give Muslims rights and freedoms when they do not give us rights and freedoms in their country?” Of course, that’s a whole ethical discussion for Christians to wrestle with, but I think that for many of us in North America, we assume that Muslims in the Middle East have a wide range of freedoms and rights, and it’s only the Christians who are being oppressed in the Middle East.

I know this is obvious to you, but I think for many people in North America, they imagine that Muslims in the Middle East have power and privilege and freedom, and they can live their Islamic faith however they like. That story throughout your book was just very poignant to me of the ways in which Muslims in the Middle East are not free, and I know that one thing you’ve said before, and you were hinting at it just there, is the freest and best place to be a Muslim in the world is actually America, which I think is really surprising to people.

Shadi Hamid: Yeah, yeah.

Matthew Kaemingk: So I don’t know what you have to say about that.

Shadi Hamid: Well, totally, and I’m still more than comfortable saying that. I thank God every day that I’m American, that I was born and raised in this country, that my parents were able to immigrate to the US and become American. In the process of watching them become American and the love that I see that they have for America, I mean, there’s so many examples of this. But I remember the first times that my parents started volunteering in local politics, and maybe joy is a slight overstatement, but maybe that’s actually part of it. There was this kind of joy of participation, this sense of ownership.

I remember when Trump instituted one of the versions of his Muslim ban in 2017, my mom went on a local TV station, and she wears the head scarf, so visibly Muslim. She was basically calling out Trump and saying Trump is contradicting the American idea. And she didn’t have to prove that. It was just natural to her that she had more of a purchase on what it meant to be American and what the American idea was than Donald Trump. And she didn’t have to apologize for that or process that. She just felt that. This was her country, and she was going to defend it against what she considered to be a violation of what it meant to be American, and there’s just . . . Any immigrant or a child of immigrants that you talk to has stories like this.

Yeah, yeah, so that’s a big source of inspiration for me. And the broader point is that, as you said, Matt, not only do Christians not have various freedoms in Middle Eastern countries, but Muslims don’t either. Now, it’s different, and when you get into specifics, we can talk about what rights are being denied to which group, but it’s outwardly and politically . . . So those who are outwardly political with their faith in many of these Muslim-majority countries are suppressed, because regimes see them as a threat because they are “politicizing religion.” And we will talk in later episodes about the fallacy of this idea of religion being politicized, and it’s very much a post-Enlightenment development to treat religion and politics as separate categories, that if religion is becoming political, therefore it’s somehow less authentically religious. We have to question that presumption, and we’ll definitely be . . . we’ll talk about that more in the future.

Matthew Kaemingk: So I want to turn us to the Obama administration for just a minute, and then I promise I will start to challenge you on your democratic minimalism. I’m going to get to that. We talked about Bush’s optimism and his desire to promote democracy, and we sort of hinted at Obama’s ambivalence. And there were a number of things within your book talking about the hesitancy within the Obama administration to protect democracy in the Middle East and to show real American force to protect these democratic movements in the Arab Spring. That came from a real ambivalence about Islam itself—is Islam capable of democracy? And one of the quips you quote is essentially one person, one vote, one time. I wonder if you could explain to our listeners what that quip meant and how quips like that played a role in causing the Obama administration not to go all in on democracy in the Middle East.

Shadi Hamid: So this phrase, it’s really a fascinating phrase because, somewhat to my surprise, I started to notice it being used in the American context in the lead-up to our midterms just a few weeks ago. And I had never heard one person, one vote, one time being used in that way. It’s yet another phrase that’s been imported from the Middle East and weaponized for internal American debates. Another example is some—

Matthew Kaemingk: So tell them what it means first. Tell them what it means.

Shadi Hamid: Yeah. So it just means that there is an election, and then a party comes to power through democracy only to immediately end democracy as we know it. So they’re using democracy to dismantle it, and that’s the idea of one vote, one time. The vote happened, and then that’s it.

Matthew Kaemingk: So in the Middle Eastern context, it’s basically, if you let the Muslims vote for who they want—

Shadi Hamid: Yeah, exactly.

Matthew Kaemingk: That will be the last moment for democracy. And similarly, in America, if you let the Trump followers vote and if you let them win and you accept that win, that would be the last democratic vote you had.

Shadi Hamid: Precisely. Yeah, so it was coined originally in relation to the potential of Islamist parties coming to power through elections. Nineteen-ninety one in Algeria is a key moment because an Islamist party was on the verge of victory. The secular military intervened to cancel the elections, which then provoked the civil war. In the mid-nineties an Islamist party came to power through elections in Turkey, and then a coup followed and there as well . . . And then, of course, we have the more recent example of the Arab Spring in Egypt where the Muslim brotherhood came to power through free elections, and then there was a subsequent military coup. So it’s interesting that these coups are justified almost on supposedly democratic grounds, that the only way to save democracy is by ending democracy.

So it’s just interesting to see how people make these justifications, but they basically say that these Islamist parties are too dangerous and they have to be stopped before they come to power. Even if they do come to power, if they stay in power too long or if they keep on winning elections, then that’s too dangerous, so on and so forth. What’s interesting, though, is one person, one vote, one time has . . . there’s maybe one or two borderline cases, but it’s never really happened in the Middle East. So what I try to lay out is that a lot of this is a fear of something that is actually extremely rare, and this alarmism is used to basically frighten people away from the democratic idea.

And especially secularists and liberals in the Middle East who are very afraid of Islamist governance, they’re worried that these groups will basically transform the identity of their countries, that Egypt will become—quote, unquote—Islamized. What’s interesting is that if you actually look at the record, it’s liberals and secularists who have more often supported coups against democracy than Islamists. Why? Because they’re afraid of mass sentiment and they find mass sentiment to be, “Oh, if the people vote, they’re going to make bad decisions,” as we’ve mentioned various iterations of that idea.

Sort of along similar lines, another phrase that was imported from the Middle East was also this idea of the deep state, which the Trump administration started using very routinely in 2016 and 2017. Which again, I love the idea—well, I don’t love it, it’s not a great thing—but I do like . . . it’s fascinating to me how ideas travel because they do have this broader universal applicability. And the idea of a deep state is that even if there’s an elected government, there is a deep state, a kind of entrenched bureaucracy that prevents the elected leaders from actually expressing the will of the voters. So as many of you all might remember, Trump was saying that the bureaucracy was preventing Trump from actually following through with his Trumpist division. Steve Bannon was very much a key proponent of this complaint. In the Middle East, it happens to be more true. We don’t have to get into all of that, but the deep state there is much more of a thing because you do actually have a military that is politicized, that constrains what elected leaders can do in a very explicit way. Sometimes they intervene and cancel elections, basically. Thank God, we don’t have that in the US context. So yeah, that’s just some more context on that idea.

Matthew Kaemingk: So let me try out your argument or your pivot towards democratic minimalism and why that’s something we should go for in the Middle East, but also you bring that more towards the United States as we deal with these sort of clashes between intense ideological groups. So, in your sense, it seems to me that you very much believe in democracy, but you have a lower understanding or a lower belief in what it actually will accomplish. That essentially at one point of the book, you talk about democracy is a peaceful way of engaging in political warfare, that it is combat by other means. So it’s a way of mitigating conflict. Democracy is not necessarily going to make society so much better. It’s not necessarily going to lead to amazing outcomes in terms of health, education, the liberation of women, or anything else. Democracy is just going to reduce conflict, and it’s going to release pressure for a conflict, violent conflict, and it will actually make things slightly more stable.

So it seems to me you’re trying to lower expectations of what democracy is going to accomplish and essentially lower expectations of exactly what democracy is. So it doesn’t have to be simply an Enlightenment liberal form of democracy. By doing that, you are distancing yourself from a sort of optimistic George Bush, this is going to free all the oppressed and create this amazing new society in the Middle East. But you’re also not willing to go a sort of pessimistic route of let’s just let the Middle East be full of autocracies and dictators.

And so you’re arguing for a more mere democracy of let’s just have . . . as the United States, in terms of our foreign policy towards the Middle East, let’s provide support to democratic movements and governments that are moving in democratic directions, and let’s remove the military support and financial support that we are actually propping up dictators around—

Shadi Hamid: Let me put a finer point on it. When I talk about democratic minimalism, part of what I’m talking about is decoupling small-d democracy and small-l liberalism, that for too long Americans and Westerners have treated democracy as a bigger package deal. So usually when people say democracy, it’s shorthand for liberal democracy, but the liberal idea and the democratic idea can be intentioned. So here we’re referring to the classical liberal tradition, which emphasizes individual freedoms, personal autonomy, the primacy of reason over revelation, the individual over the collective, minority rights, gender equality, and so forth. These are a package of substantive ideas about what a good society should entail. Not all democratic processes are going to lead to those liberal outcomes.

In a recent episode, and for those of you who missed it, you really should listen to it, we had a post-liberal, Christian theologian, James Wood, who talked about even the idea of moving beyond liberalism or thinking beyond liberalism in the American context. So again, this is not just a Middle East thing where we talk about those who are illiberal, non-liberal, or post-liberal. It is also a growing movement intellectually here in America and in western Europe as well, where—is liberalism the final endpoint of humankind or is it okay for people to search out alternatives?

So for me, democracy, if I want to bring democracy . . . to make it something more manageable and digestible for people so we don’t ask too much from them, what I’m saying is that, let’s see it as a conflict-regulation mechanism. That democracy is fundamentally about alternating power, the peaceful transfer of power through regular elections. It’s about being responsive to the electorate, even if the electorate wants bad things. And once we move away from this outcomes-oriented approach to democracy, we can start to appreciate democracy more because we’re not expecting it to give us other things. That, to me, is what’s really presented a number of hang-ups for Americans. We don’t even really know why we believe in democracy anymore because we’re attaching so many different things to it. What if we get down to basics? And that way we can make the argument more clearly and explicitly to our fellow Americans. Listen, all we need you to believe in is this, that you respect democratic outcomes that are not to your liking. That’s it. That’s all you got to do.

Now, for some people that’s a lot, but also, if you think about it, it’s like a pretty straightforward thing. It’s not an ideological request. We’re not asking people to transform themselves into liberals or to believe something about abortion, if abortion is part of our conception of gender equality, because that goes against people’s theological convictions. But believing in the peaceful transfer of power through elections, as far as I know, doesn’t go against anyone’s essential theological conviction.

So we’re not asking a Christian to choose between democracy and their faith, and that’s important because you don’t want to put people in a position where they have to choose. Because if we tell them, “Oh, democracy means liberal democracy, and liberal democracy means gender equality, and gender equality means that every woman has an innate right to have an abortion,” then obviously that’s a different package of things that we’re asking of someone, and a lot of people are going to say no. Or if we say that democracy requires secularism, what about people who aren’t secular? Or what if we say democracy requires equality before the law, and equality before the law means that you have to support gay marriage? A lot of Christians, especially evangelicals, are not going to be able to sign on to that, and we don’t have to like it. This is very clear. We don’t have to like any of this stuff. We can say, okay, these are morally . . . we can say from a secular standpoint that it’s morally abhorrent for someone to oppose gay marriage. But they have a right to believe in things that we consider to be morally objectionable. People have convictions, and we shouldn’t try to push people to give up their own theological convictions.

Matthew Kaemingk: So here is my challenge. After a long wait, I completely am all in on lowering our expectations of what democracy can provide and also lowering the bar of who is allowed to participate in democracy. I think we should have a very wide bandwidth of who is allowed to participate and a low standard of what we expect from democracy. So I’m 100 percent in on that.

What I object to is your description of democracy as merely a mechanism, as simply a form of government, a form or a mechanism for dealing with conflict. The reason is . . . and what I’d like to do is pivot to a couple of different quotes that I put at the very beginning of one, of my first book, that have sort of animated me for a long time when it comes to democracy. The first is from T.S. Eliot.

T.S. Eliot says, “The term democracy, as I have said again and again, does not contain enough positive content to stand alone against the forces that you dislike. It can easily be transformed by them.” And what I take to mean there is that democracy itself needs some more substance. As you say, you’re a believer in democracy. It takes belief; it takes a commitment to live with the difficult and sometimes frustrating results of democracy. Democracy actually demands a lot of us. It’s not merely a mechanism; it’s actually kind of a way of life.

The second one comes from John Plamenatz, and he says that, historically speaking, the freedom of religion, freedom of religion does not come from indifference. It does not come from skepticism or simply out of mindedness. He says it comes from faith and actual belief in something.

So what I want to say here is that it’s not enough just to lower our expectations and merely support democracy as a mechanism, but actually democracy requires a great deal from us as persons. In fact, throughout the end of your book, you talk a lot about the emotion involved in living with deep difference, in living alongside people that frighten us and would even wish us harm. You use a lot of actually emotional language to talk about just the experience of citizens living amidst deep difference. It seems to me, going off of T.S. Eliot, that democracy actually requires a lot from its citizens compared to, say, dictatorship or whatever else. Democracy demands that citizens handle this deep difference in an at least somewhat open-minded and open-hearted way.

So what I want to push you on is that democracy is not simply a mechanism, and if we treat it as just a mechanism, it won’t last for very long. And that’s not an anti-Islamic statement. I say that specifically for the American context as well. In order for American democracy to endure, it has to be more than just a mechanism, it has to be something that we really believe in, and it has to be something that we practice on a day-to-day basis. That’s big, so that’s what I want to push you on, Shadi, so let’s go.

Shadi Hamid: Now for the pushback to your pushback. So I disagree that democracy can be considered a way of life, and maybe you meant that slightly hyperbolically. But when I think about the phrase “a way of life,” I think about Islam. It’s often said that Islam is a way of life, right? Religions, to various degrees, organize our lives in some amount of minute detail. It’s a way of anchoring your every day. I’m a pretty staunch believer in democracy, but can I honestly say that the idea of democracy is an anchor for me that orients my daily life? I think that’s pushing it a little bit, and that’s why I think democracy is not comparable to other ways of life. I would say that democracy doesn’t have any inherent ideological content, because you can be a socialist or a communist or an Islamist or a liberal or a leftist who supports democracy or comes to power through democracy. It doesn’t have any implication about what your ideological endpoint is. You can still keep your socialist or Marxist or Islamist ideological endpoint. You just have to agree to the mechanism and the procedures that alternate power through regular elections and are responsive to the electorate and so forth.

But I think you get to a little bit of a tension in my argument, and I don’t know if I can fully resolve it for you, Matt, but I’ll be curious what you say. You say that democracy needs to be something we believe in as Americans. Why can’t . . . I agree, but why can’t we strongly believe in a mechanism or a set of procedures? There’s almost this dichotomy that you pose between believing in something and something being a mere mechanism. So I’d be curious how you would play out that tension.

Matthew Kaemingk: Well, I think in some ways people aren’t willing to march and die merely for a mechanism. They have to believe that it’s something more than just a mechanism. Furthermore, I want to push you on page 236 of your book. That is where . . . this is where you—

Shadi Hamid: Coming with the quotes. Okay.

Matthew Kaemingk: This is where you got my hackles up, man. It has to come when you start talking about rights. And you say essentially that rights are not freestanding, self-evident, or morally transcendent.

Shadi Hamid: Oh damn.

Matthew Kaemingk: They have a more specific purpose, and they’re not too dissimilar from Robert Dahl’s view described as follows. Robert says, “Rights are at root procedural, not sacred, political attributes, not ontological features of persons. Free speech, for instance, is necessary to challenge government and to provide citizens not only with the information but also with the choices of their destiny.” So describing rights as nothing more than procedural, as not morally transcendent, that seems to be in tension with the earlier theological statement you make that God made us to be political animals and that’s something inherent to us. That sounds like a morally transcendent, ontological reality that you are talking about. Then you pivot here to Robert Dahl, who says, you know, rights are useful as a procedure for challenging the state, but they’re not real things.

Shadi Hamid: Yes. Okay. So I think there’s two levels of analysis here. I personally can think that certain rights are morally transcendent because they come from God, that we are endowed by our Creator with these in inalienable rights. I just don’t know if I can impose or promote that understanding to everyone else and expect them to sign on, because that is specific to my monotheism, but it’s also specific to my particular understanding of Islam, because obviously there are many Muslims who don’t feel as strongly about democracy as I do. So even among Muslims themselves, there is disagreement, and we talked about some of those disagreements in the previous episode.

So this is where I become . . . this is where sometimes people criticize me for being a bit of a moral relativist. I think that people can be moral absolutists in however they want to view the world. I just think we have to assume that other people aren’t going to agree with us. So can I really say that universal rights are universal if they’re not universally held? What makes something universal if 20 percent of the population doesn’t agree that they’re universal? And I have no way of definitively proving that to them because if my belief in rights as transcendent comes from my belief in God and they don’t believe in God, then where does that leave us?

Or to give another example, and actually this is very relevant too, because I literally thought to myself, I wonder what Matt would say to this. In other words, WWMD, “What would Matt do?” which sounds like weapons of mass destruction with two Ws as well. So I was at Christopher Newport University, not that that’s particularly relevant, but I was talking to these very well-meaning young students, undergrads—it was just maybe four of us—and I was trying to lay out the case for suspending judgment. So basically one of the students was saying that if someone doesn’t believe in the full panoply of trans rights and on gender identity, the expanded notion of it that’s become increasingly prevalent among the younger generation, she said, “Why should I tolerate people who have traditional views on gender identity and don’t recognize that there are growing number of people who are non-binary?” I’m like, “Well, look, you can have your view. Why not just allow them to have their view too?”

I mean, their view is coming from a place of conviction. If they are traditional Catholics or evangelicals or Muslims, their beliefs may not allow them to have this expanded understanding of gender identity. But then she kept on coming back and being like, “Well, why?” And I guess I said, “Well, not everything is about the here and now. Why not just suspend judgment?” But then she was like, “Why should I suspend judgment?” But then I thought the reason that I believe in the suspension of judgment is tied to God and there being another life, that not everything is in this life. And that’s why, as we’ve talked about in previous episodes, we don’t have to obsess over everything that is human and temporal because we know that there are other things.

I was like, I don’t want to presume that you . . . I was hoping that she would just admit that she believed in a higher power, but then she was like, “Well, this is part of the problem. I can’t follow your train of thought because I don’t believe in a higher power. I’m an atheist.” So I was actually stumped.

Matthew Kaemingk: Yeah.

Shadi Hamid: And I was like, what would Matt say to this?

Matthew Kaemingk: What would Matt say?

Shadi Hamid: I know that’s like a little bit of a tangent but—

Matthew Kaemingk: Yeah, I think honestly the only thing you can do at that point, and I’ll be curious to what you say to this, is you have to ask the atheist . . . you have to say, “Here is how I make space for atheist in democracy, and here is how actually I think God commands me to make space for you in democracy.” That’s what I would say. I believe that God commands me to make generous, just, and free space for atheists in American life. God commands me to respect them, and even more God commands me to love atheists.

Then what I would do is I would turn to her and I would ask, “How are you going to make space for me?” And I can allow her to just say, “No, I don’t want to make space for you. You are a white cis male, evangelical, and I would like to get rid of you. You are problematic.” Right? And allow her to honestly state whatever her answer is to me. I would hope she wouldn’t say that to me, but I think it really is to pose the question back to them: How are you going to make space for me? I can’t answer that for her.

Shadi Hamid: Yeah, okay, but if they say no precisely as you suggest right there, then is that something that we can live with in democracy, if a large number of people say, “No, we’re not going to even make space for the other”?

Matthew Kaemingk: Yeah. I think that a healthy democracy can handle a small amount of undemocratic, illiberal citizens, and it will always have to. But there is a tipping point when you get to too many illiberal and undemocratic people, that it falls, and democracy, as you argue in your book, is potentially a fragile thing. It’s not an automatic thing. So it can produce non-democratic results, and part of being a believer in democracy means that you’re willing to accept the risk of elections, that you can lose.

Shadi Hamid: Well, just to clarify, so you said that if too many people are undemocratic or illiberal, then there’s a threshold at which things get pretty fragile. Did you mean to say both of those things? Because those are two different . . . as we’ve said, democracy and liberalism are not coterminous. What if a majority of Americans are non-liberal or post-liberal? Do you feel like that’s simply too many and that’s going to be unacceptable? Do you think there has to be a majority of Americans who still hold true to the classical liberal tradition in some form?

Matthew Kaemingk: No, not for democracy to endure. For liberalism to endure, you need—

Shadi Hamid: Naturally.

Matthew Kaemingk: No, not for democracy to endure. But I think that ultimately I am for taking the risk of democracy, and I’m willing to live with that risk. And I’m willing to live with the fact that American democracy is not immortal, and there will come a day when it falls. But I’m committed to it.

Shadi Hamid: Wait, just time out on that though. I’m interested by what you just said. There is a day when it will fall. Can you just say what you mean by that?

Matthew Kaemingk: Well, being a Christian, I believe that there will be an end to this world, that all things will pass away. So American democracy is not immortal. There is nothing in Scripture that promises me that America will last forever. So I hold American democracy loosely in that sense of American democracy will exist for a specific time and place, and then it will be gone. So I’m 100 percent committed to it because that’s what I’m called to.

Shadi Hamid: Yeah.

Matthew Kaemingk: But I think—

Shadi Hamid: Okay, another question for you—

Matthew Kaemingk: No, no, I’m in charge now, sir. [laughter] Earlier on when you responded to me, you said, “Essentially, I don’t want to impose on other people over too much belief on what democracy is.” And I think that I don’t want to impose upon Muslims my Christian theology of democracy, or on atheists my Christian theology of democracy. I want to ask them, how are you going to live with deep difference and how are you committed to democracy? Because I’m a pluralist, I am well aware that a socialist is going to make a case for democracy that’s different from my case for democracy, that there are a wide variety of ways to value democracy. What I’m saying is that the ways in which we value democracy, we have to hold it as something like, something sacred. Not simply just a mechanism like the telephone company—I pay my bill; I believe in the telephone company, so I pay my bill. Democracy is something more. Believing in democracy is something more than believing in the telephone company. It has to have this sort of sacred value that you are willing to endure difficulty, injustice, fear, frustration. You’re willing to march. You’re willing to go fight. It demands something more than just simply accepting it as a mechanism that’s an important part of our life. That’s what I’m trying to say.

Shadi Hamid: Yeah, yeah. No, that makes sense to me, but don’t you think I treat democracy as pretty sacred? I mean, I’m utterly preoccupied with it. I do use the language of belief and faith in the democratic idea. I guess I would just say, why can’t a mechanism be sacred? What is it about the—quote, unquote—telephone company that prevents us from really being into the telephone company?

Matthew Kaemingk: Yeah, that’s what I’m trying to point to. I believe democracy is sacred to you, and I believe it means something a lot. I think it means a lot to you, and that’s what I’m trying to say is, it’s not just a mechanism to you. It’s not mere democracy to you, and a lot has gone into your own story of your commitment to democracy. And you tell the story of your mother defending democracy, and I know, deep down in your heart, you are deeply proud of your mom, and you should be. And it’s not just because democracy is a mere mechanism. There’s something moving in you. And I think that in order for democracy to exist, in order for democracy to handle the challenges of Donald Trump, of terrorism, racism, and all the other challenges that are facing democracy, you need citizens who are not simply treating it like a telephone company, but who really do believe in it.

So what I’m trying to say is, Shadi reveres democracy. He doesn’t simply treat it as a mere mechanism or a form of government. So that’s my push on you.

Shadi Hamid: No, no, I like that. That helps me understand a little bit more. So in terms of making the case to other Americans to believe the way that I believe, what to you would be in this thicker, more worthy conception of democracy? Because I want to make sure that we get to the practical implications of what you’re saying. I might disagree a bit. So is it a lot to ask someone to accept a democratic outcome not to their liking? Is that actually a big ask of our fellow Americans? How hard is it to go through the midterms and, if the Republican that you hate in your district wins, for you to accept that? I mean, there is an interesting question about how hard is it to actually accept—quote, unquote—bad democratic outcomes. Clearly, a growing number of Americans are struggling with it, so I guess for them it’s becoming harder. But does it have to be harder?

So that’s maybe one thing, but also let’s try to think through . . . I want to hear what you think about the thicker conception of democracy when we’re making the case to our fellow Americans.

Matthew Kaemingk: I was being hyperbolic when I described democracy as a way of life. It’s not a way of life, but I love Alexis de Tocqueville and I love civil society theory, and I think that it’s fundamentally right that we learned democracy through dinner-table conversations, taking turns. We learned democracy through participating in the PTA, through participating in church or mosque discussions and debates in our neighbourhood housing associations and wherever else. In these sort of democratic exchanges throughout our lives, we learn to lose sometimes. We learn to negotiate. We learn to compromise. And it’s through practicing these sort of democratic values in our families, in our neighbourhoods, in our clubs and organizations, that we get better at losing. We get better at accepting the results and remaining committed to communities that let us down sometimes.

So I think that in order for American democracy to exist, you need a critical mass of citizens who are practicing democracy in their daily life, who believe in its sacred value, and who will fight against its desecration. Now, any democracy can handle a group of slackers, a group of people who don’t care, who aren’t engaged, and any democracy can handle a group of people who are just anti-democratic and do not practice these things and try to actually undermine them. I think what the past five, ten years has done is remind us of the importance of the practicing of democracy in our daily lives.

And here’s where I’m going to get practical. Really, what American society needs is—on that sort of daily basis of everyday citizens in homes, schools, shops, factories, community centres—participating in democratic debate, engaging in interfaith and inter-political friendship, and really doing this. We just got out of Thanksgiving, and of course many people were trying not to talk about politics and religion at the dinner table. But I think that, Shadi, what you and I are inviting people to do is to actually take that risk and consider those priors, those first principles that you want to engage, that America depends on those things. I realize I’m sounding very, very romantic and George Bushy right now about democracy. I’m okay with that. So I think democracy requires a little bit of romance, a little bit of civil religion.

Shadi Hamid: I like that, a little bit of romance. I can definitely agree pretty strongly that the practical implication from either of our perspectives is you have to be willing to take a risk, and that’s something that each person can do in their own lives, in their own communities, with their family members and friends. Maybe that won’t change things on the mass level, but it’s something that you have control over, because part of the theme, as we’ve touched on a number of times, is I believe in democracy because I believe people should have agency. They should have some say over their destiny. They should have some say in who their leaders are. So it really does come back to what individuals can, should, and will do in their own lives.

And Thanksgiving—I’m glad that you brought that up, because that’s a good example. Just imagine your most tense Thanksgiving dinner and the choices that you made in real time about what to say or not say. We do this throughout our lives, and we don’t even realize we’re making calculations—not always careful ones, but they still are calculations—of what we want to say or how we want to criticize or how we want to take exception to something someone else has said on the table, in our vicinity.

Just to share my own Thanksgiving story, there were a couple moments that I chose not to jump into the conversation, and I guess I was fine with that. I could have opposed; I could have made an issue. But basically there were some pretty strong statements made with some family friends about how basically the Republican party is just wholly bad and Trump supporters are bad, that basically we should find ways to restrict their role in public life and that sort of thing. I just wanted to kind of push back, but I realized that to kind of lay out the case for rethinking that would’ve caused consternation and probably wouldn’t have been productive and would’ve derailed the entire conversation. I didn’t want to talk about Trump voters for an hour. That to me was a calculation that I made.

Now another . . . and then there was another example where one of the dinner-table participants said basically something along the lines of the idea of God is kind of absurd when you really think about it. I was just thinking about my mom. Is my mom going to feel a need to step in and make a strong objection? She decided to not get into that too much. You’re not going to convince someone. It’s okay. If someone else thinks that the idea . . . it was actually this, the idea that there was a literal heaven and hell. And so this friend of ours was basically like, “When you really think about it’s silly. There’s actually a physical space where there’s heaven, and for some reason it’s above. And then there’s this physical space called hell, and we assume that it’s below, and apparently people get burned.” He was just walking it through and he is like, “This is silly.” But that’s a pretty creedal, a pretty foundational idea in Christianity and Islam. My mom did take issue with the notion that hell or heaven are in particular physical spaces because we’re reducing the afterlife to human understanding of space, and the afterlife is beyond the human conception of space.

But putting that aside . . . anyway, this is just to say that those are pretty foundational differences between friends or family, and you have to think about what the best way of engaging is and what the most appropriate venue for that engagement is.

Matthew Kaemingk: Yeah, and being right—

Shadi Hamid: I don’t know if that resonates with you.

Matthew Kaemingk: It does and I think—

Shadi Hamid: I don’t know if you would’ve fought back on the dinner table yourself, but—

Matthew Kaemingk: Well, I think it points to . . . there was another value at play for you and your mother, which was maintaining the relationship, staying at the table. We’d like to have another Thanksgiving. We don’t want this to be the last, right? So I think similarly in democracy we don’t want this to be the last election. We make calculations about what we’re going to say and what we’re not going to say and what we’re going to do and what we’re not going to do. I mean, there is just really something to say about the dinner table as the place where we learn democratic practices and democratic manners and things like that. I think this might be a good place for us to wrap up our conversation. So with that, Shadi, would you take us out?

Shadi Hamid: Yeah, yeah. Well, first of all, thanks, Matt. I really enjoyed this conversation. Thanks for raising these really thoughtful issues and criticisms of different parts of my argument. I know that I’m going to be thinking more about what you said, and this is what I love about our interaction. We’re just perpetually learning from each other in real time, and it’s great to have all of you dear listeners at the table with us, the metaphorical table of course. Which is to say, thanks for listening to Zealots at the Gate. If you like what you heard, make sure to subscribe, make sure to give us a review or a rating. If you want to learn more about the podcast and our sponsor Comment magazine, definitely go to comment.org where you’ll find illuminating essays on politics, culture, and faith. Matt and I want to hear from you all. Connect with us over Twitter at our respective handles. Mine is @ShadiHamid, and Matthew’s is just his full name too, @MatthewKaemingk. Note the Dutch spelling. Or you can write to us at the hashtag #zealotspod on Twitter or email us directly at zealots@comment.org.

We can’t guarantee that we will agree with you, but we can guarantee, I think for the most part, a sincere exchange. We’d really welcome your thoughts, comments, and criticisms. Thanks as well to our sponsor, Fuller Seminary’s Mouw Institute of Faith and Public Life.

Matthew Kaemingk: Zealots the Gate is hosted by Comment magazine, produced by Allie Crummy. Audience strategy by Matt Crummy, and editorial direction by Anne Snyder. I’m Matthew Kaemingk and with me is . . .

Shadi Hamid: Shadi Hamid.

Matthew Kaemingk: See you later.

Shadi Hamid: Thanks for listening, everyone.

Matthew Kaemingk: Bye.

Shadi Hamid is a columnist and editorial board member at The Washington Post and an assistant research professor of Islamic studies at Fuller Seminary.

Matthew Kaemingk is the Richard John Mouw Assistant Professor of Faith and Public Life at Fuller Theological Seminary where he also serves as the Director of the Richard John Mouw Institute of Faith and Public Life.

Love the show? Help others find it by reviewing it on your favourite podcast app. We also welcome your ideas and feedback. Email us at zealots@comment.org. Thanks for your support.