I

In the public health profession, everybody wants to be on the community’s side. Phrases like “community-centred” and “community-engaged” are commonplace. Courses on community engagement are typical in master of public health curricula. Funding streams frequently emphasize the importance of established community relationships among researchers who wish to conduct “community-based” studies. It would seem as though the work of public health is intimately bound up in the idea, structure, and activity of communal life.

Whenever I read the word “community” in a public health report, I think about the small group of guys I meet with every Thursday morning at a local coffee shop. Every week we arrive around seven and hang out for as long as each of us can until we must get to our various jobs. There’s never an agenda for our gathering, and topics of discussion range widely—from politics to religion and everything in between. That we all attend the same church is our major common denominator, but our approaches to faith, our political interests, our jobs, and our hobbies vary considerably. When I think about what makes my life meaningful, I cannot help but think about those Thursday-morning gatherings and those friends. I have had some of the best memories of my life with them, and they have made difficult moments of my life bearable.

Sadly, we live in a world in which such friendships are vanishingly rare. Our communities are in bad shape. One of the most unmistakable and disheartening trends in the last several decades, starting at least in the 1960s, is the precipitous decline in communal life in the United States. Social sciences literature often refers to this trend as a decrease in “social capital”—the networks, relationships, and norms of trust and reciprocity that enable individuals and communities to work together effectively. In Bowling Alone, originally published in 2000, Robert Putnam documented how vast indicators of social capital had steadily declined in the second half of the twentieth century. During this period, membership in traditional civic organizations (e.g., Lions Club, Rotary Club) fell by roughly 50 percent, and between 1970 and 2020 the percentage of Americans who reported spending time with their neighbours several times a week decreased by 35 percent. Weekly church attendance, a key source of regular social connection for many, dropped from about 48 percent in the 1950s to 36 percent by the late 1990s and hovered around 30 percent in 2022. What Alexis de Tocqueville, the nineteenth-century French chronicler of American life, once described as “the art and science of association,” an ability he uniquely praised Americans for developing, has become a lost art in most locales across the country.

One of the hallmark features of these trends is our “epidemic of loneliness and isolation,” formally recognized in 2018 by Vivek Murthy, the former United States surgeon general. In his 2023 Advisory, he laid out a new reality: we now live in a society in which one in two adults in America reports experiencing loneliness, and only 39 percent of adults feel very connected to others. Rates of loneliness are now higher than other commonly recognized chronic diseases, including smoking, diabetes, and obesity. He also noted that social isolation is as harmful to human health as a lifetime of smoking cigarettes; several studies have documented the link between social connectedness and reduced risk of all-cause mortality. The negative health effects of loneliness are remarkably consistent across different cultures, suggesting the universal mechanisms underlying the association.

Regrettably, the gradual decay of quality social connections and the rise of loneliness is a problem that is only getting worse. The General Social Survey (GSS), which has been conducted since 1972, has shown that the number of Americans reporting that they have no close friends has increased dramatically. In 1990, only 3 percent of GSS respondents said they had no close friends; by 2021, this number had quadrupled to 12 percent. The percentage of individuals who could count ten or more close friends has also dropped significantly, from 33 percent in 1990 to 13 percent in 2021. The amount of time Americans spend with friends in person has also been cut, from roughly sixty minutes per day in 2003 to twenty minutes per day in 2020, a reduction of nearly 70 percent in just two decades. Given declines in social capital more broadly, there is nothing to suggest that increasing rates of loneliness are going to plateau unless something is done to intervene. As the journalist Derek Thompson has written, “Self-imposed solitude might just be the most important social fact of the 21st century in America.”

While these statistics paint a sobering picture, our crisis of loneliness and isolation is ultimately one faced not by abstract collectives—mere changes in aggregate percentages—but by individual persons who once thrived within communities of close social connections. I think about the elderly in my neighbourhood who live far from any family, and who struggle to navigate a world built for cars they can no longer drive. I think about the teenagers I speak with at my church who spend upward of twelve hours on their phones each day, disconnected from the real world. I think about the stream of young adults who move to my city each year in search of employment or education, but who struggle to find friends outside their demanding work schedules, and for whom the transiency of their work makes it likely that they will soon uproot their lives and start all over again in a different city. I think about all the young parents, especially mothers, who feel as though they must raise their children in utter isolation, and for whom many evenings are spent alone in their homes. Even the surgeon general’s report begins not with a litany a statistics but with an account of the stories he heard while first conducting his “listening tour” of the country in 2014: “People began to tell me they felt isolated, invisible, and insignificant. Even when they couldn’t put their finger on the word ‘lonely,’ time and time again, people of all ages and socioeconomic backgrounds, from every corner of the country, would tell me, ‘I have to shoulder all of life’s burdens by myself,’ or ‘if I disappear tomorrow, no one will even notice.’”

The Inner Logic of Technique

The surgeon general’s report has prompted those with a concern for the public’s health to take interest in the causes of social isolation and loneliness. I believe it is critical to identify these causes at their root level, going beyond any one manifestation. To defend the goods of social connection and communal life, public health practitioners must be able to define its opposite in all the ways it can possibly manifest. And yet I believe this is a worthwhile task not only for those who formally belong to the profession but for all of us who take interest in making our world a less lonely place. Public health is, at best, what we all do to make our world healthier.

The causes of our loneliness epidemic are multi-faceted and overdetermined: they likely range from a cultural tendency toward individualism to a secularizing population without consistent, common places to worship together. One of the major sources of social disconnection, as identified by the surgeon general’s report, is our increasing dependence on digital technologies as the primary platform for our social connections. When we interact with others on social media (or through email, Zoom, internet chat rooms, etc.), we interact with mere fragments of those people, even if the number of people we can connect with is much higher. While our social media account may have hundreds or even thousands of followers, it is rare that we know many of them by name. The quality of our relationships is replaced by the quantity of our relationships.

Beyond any of these individual forces, I’d like to suggest that a fundamental cause of this epidemic may not be a particular social movement or social institution or even a specific device, but rather a more fundamental posture toward the world and other people—one in which the felt need for social connection and community has been displaced by a substitute. The name of that substitute is technique.

Within a technocracy, the primary method of dealing with social problems is technique, the primary mechanism of knowing the world is technique, and the primary mechanism of connecting with others is technique.

In his 1954 book The Technological Society, twentieth-century Catholic social theorist Jacques Ellul defines technique as “the translation into action of man’s concern to master things by means of reason, to account for what is subconscious, make quantitative what is qualitative, make clear and precise the outlines of nature, take hold of chaos and put order into it. . . . What characterizes technical action within a particular activity is the search for greater efficiency.” Technique renders null the unnecessary or complicated portions of a task—often natural sources of ambiguity and spontaneity—and reassembles them toward the end of improving efficiency. The motivation for this restructuring is the desire for mastery. But that which is unpredictable and spontaneous is, by definition, outside one’s mastery, and therefore technique seeks to eliminate such forces as they present themselves within the sphere of activity. As Ellul notes, “The ideal for which technique strives is the mechanization of everything it encounters.”

Ellul further argues that the practice of technique is not limited to specific devices that we traditionally associate with modern technologies (e.g., phones, cars). Virtually all our institutions are built around the inner logic of technique: “The term technique . . . does not mean machines, technology, or this or that procedure for attaining an end. . . . Technique is the totality of methods rationally arrived at and having absolute efficiency . . . in every field of human activity.” Indeed, while one may often think of technocracy as rule by so-called technocrats, it is more fundamentally a society ruled by the mechanism of technique. Within a technocracy, the primary method of dealing with social problems is technique, the primary mechanism of knowing the world is technique, and the primary mechanism of connecting with others is technique. The mass consumption of television, for instance, contributes to a technocracy by transferring the ways in which we entertain each other to the medium of digital technique. As sociologist Ray Oldenburg writes in The Great Good Place, “Television brings the rest of life into the home. ‘Don’t go out and live,’ say the television programme chiefs. ‘Just stay in the privacy and comfort of your own homes and we’ll live it up for you.’”

Insofar as technocracy seeks to displace that which is uncertain, unstandardized, and ambiguous—factors of life that prevent the unmitigated expansion of technique—it will always, ultimately, tend to displace the primary source of all such variance: the human person, a messy combination of unpredictable agency, incomplete knowledge, disordered passions, and contradictory beliefs. The surgeon general writes that technology at times “displaces in-person engagement.” This displacement is true to a much greater extent than is often appreciated. At its extreme, technocracy tends toward the systematic removal of people from all activities of human life—entertainment, cooking, transportation, education, and even friendship. Other people, when treated as people, are messy and challenging to deal with—they have their own agency, fears, and biases, all of which make it challenging for technique to operate at the maximal degree. Technique, stretched to its limits, is the singular force that can render the entire world impersonal.

Technocracy as Alternative to Community

Published in 2011, Sherry Turkle’s Alone Together is an excellent study of how we often expect from the technological world more than we can gain in the real world, and how it is often the very vulnerabilities we have navigating human relationships in the real world that the technological world is designed to address. Turkle’s primary focus in Alone Together is on the development of personalized robots that are designed to “solve” the vulnerabilities of everyday life, especially the vulnerabilities we have in our most intimate relationships. A consistent theme of the book is our desperation for this kind of technology to serve as a stand-in for such difficult relationships, providing us with what we want from the relationship without the messy cost. We often try to “navigate intimacy by skirting it,” she writes. “We insert robots into every narrative of human frailty. People make too many demands; robot demands would be of a more manageable sort. People disappoint; robots will not. When people talk about relationships with robots, they talk about cheating husbands, wives who fake orgasms, and children who take drugs. They talk about how hard it is to understand family and friends.”

If individual machines are presented as “alternatives to people,” then technocracy writ large is the alternative to community. Insofar as technique has the tendency to displace the natural agency of people with its mechanized protocols, the transition to a technocratic society will eclipse the most essential unit of community: personal relationships. At the heart of the technocratic posture is the desire for more while doing less. It is in the interest of technocracies everywhere to expand the power of what we can do while minimizing the involvement of other people as much as possible. When the reach of technique expands, someone somewhere has become that much less needed and therefore that much lonelier.

Why is this? In The Four Loves, C.S. Lewis observes that, at its core, friendship must be about something: “The very condition of having Friends is that we should want something else besides Friends. Where the truthful answer to the question Do you see the same truth? would be ‘I see nothing and I don’t care about the truth; I only want a Friend,’ no Friendship can arise—though Affection of course may. There would be nothing for the Friendship to be about.” The best and most sustainable friendships are by-products of mutual dependence oriented toward achieving a positive good—a work project, a family, a volunteer service. It is through such ventures that we come to see the worth of the other and our dependence, to various degrees and in various ways, on the abilities of the other. Friendship cannot simply be “supplied”—it does not exist outside the authenticity of this collaboration.

It is in the interest of technocracies everywhere to expand the power of what we can do while minimizing the involvement of other people as much as possible.

For instance, a few summers ago, my friends and I experienced car troubles at around the same time. Instead of separately bringing our cars into the shop, we decided it would be a good opportunity to learn about how to fix our own vehicles together. For several weeks in a row, we met at each other’s houses to work on one issue after another—switching out old brakes, alternators, spark plugs, power-steering fluid, and so on. Of course, it would have been far more “efficient” for us to bring our cars into the shop and pay a professional to fix our problems—no need to coordinate timing, no need to search the internet for answers, no need to get dirty. The mechanisms of technocracy would have enabled my friends and me to “solve” the problems of our cars without the need to ever speak to one another. And yet each time we worked together provided a new opportunity to get to know each other and converse about all things non-car-related. Our friendships deepened.

Because of this mutual dependence, friendships in a technocracy are rarely engaged in great projects, for the biggest projects are accomplished by the operations of technique. Because friendship must be pursued through means outside the regular needs of one’s life, it is rarely pursued at all. In a technocracy, one does not access food from one’s friend, or go to a friend to have one’s car fixed, or work with a friend to provide mutual child care, or ask a friend to repair a shed in one’s backyard—all these tasks are done by someone who will likely never be remembered by name and who is not known to the individual in need for more than the single task for which they provided assistance. My story about car maintenance is thoroughly mundane. And that is my point. The ultimate outcome of a technocratic society is a reality in which fewer and fewer people can or even wish to join in common projects to address the ordinary demands of life. The image of such a society is not far from Lewis’s description of hell in The Great Divorce—a sprawling city where people constantly move farther apart from each other, not so unlike many of our modern-day suburbs.

A community is a lot of things, including a unique system of values and beliefs about the world, as well as a wide range of traditions and practices, some existentially profound, some mundane. But supporting all these is the essentially cooperative dimension of most activity. Communities do things together. As Aristotle observed, within community “friends are an aid to the young, to guard them from error; to the elderly, to tend them, and to supplement their failing powers of action; to those in the prime of life, to assist them in noble deeds.” Insofar as the mechanization of technique displaces the need for human agency in all spheres of life, it robs us of the ability to meaningfully collaborate with others, and therefore robs us of the possibility of friendship and thus of community itself.

Parental Stress and Youth Mental Health: Two Case Studies

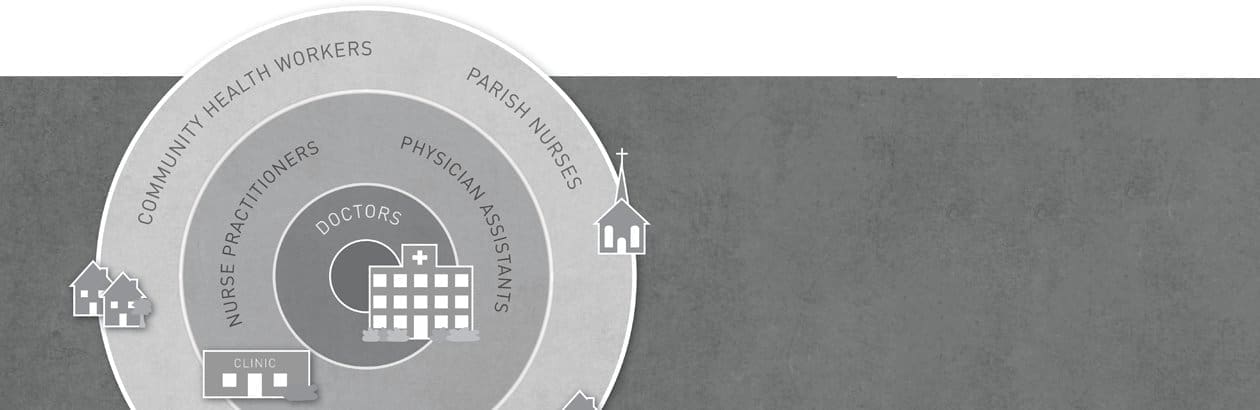

The essential dichotomy between community and technocracy lurks in the background of two other advisories from the former surgeon general. The first is on the declining mental health and well-being of parents. According to this report, approximately one-third of US parents report high stress levels. This stress not only affects parents but also has a direct effect on children’s mental health, as children of stressed parents are more likely to face issues such as anxiety and depression. This was not always the case. The proliferation of parenting experts reflects a critical shift in societal norms. Historically, raising children was seen not as an individual skill set requiring specialized expertise but as a collective responsibility shared by extended families, neighbours, and communities.

The modern focus on “parenting” as a personalized, technique-driven endeavour (indeed, its own verb) has coincided with the erosion of these communal networks, leaving parents isolated and reliant on professionals to fill the gap once occupied by shared wisdom and social support. Weakening community bonds exacerbate this trend, transforming what was once an organic, collective process into a privatized, often competitive (and therefore stressful) task. The privatization of child-rearing, driven by a burgeoning industry of parenting books, seminars, and self-styled experts, has served to alienate parents from the very social ecosystems that historically provided the scaffolding for raising well-adjusted children.

Science as the dominant form of knowledge becomes increasingly necessary as other, more personal forms of knowledge are eliminated. This creates a vicious cycle: the more one comes to depend on expert knowledge in the management of an increasing percentage of life’s affairs, the more one has no other recourse for assistance. The rise of parenting as a science reflects how much we have come to depend on expert knowledge to guide us. It is not incidental that the practice of parenting has become more challenging and stressful. As the standard of knowledge has shifted to become more scientific (and therefore more reflective of law-like generalizations that can be applied to all people to generate results), so has the perceived standard of “performing” for raising children. Parents who attempt to raise their children in a society that has become dominated by a scientific approach to parenting have few other options to turn to with the myriad questions that arise while raising their children. New parents in a community, however, will likely be surrounded by older parents who have passed through the experience and are able to pass down what wisdom they have inherited from previous generations.

Or consider another of the surgeon general’s advisories: the current epidemic of youth mental illness. In 2021, the CDC released its most updated survey of youth behavioural and mental health—the Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS). The survey estimates that among high school students, nearly two in five individuals experienced persistent feelings of sadness or hopelessness during the past year, and nearly one in five high school students had seriously considered suicide. The 2023 surgeon general’s advisory “Social Media and Youth Mental Health” makes a strong case for considering the rise of social media usage among youth as a primary cause of this epidemic. He notes that more than three hours of social media a day has demonstrable effects on increasing the risk of poor mental health among adolescents, especially for mood disorders such as anxiety and depression. The mechanisms by which excessive use of social media leads to poor mental health outcomes in teenagers are myriad: increases in cyberbullying, addiction and withdrawal, exposure to maladaptive behaviour (e.g., self-harm and disordered eating), sleep deficiency, increasingly sedentary behaviour, and limited development of pro-social coping behaviours.

Unlike housing or food, one cannot scale the provision of a discrete good called “social connection” that can be easily “referred to” for individuals in need of this service.

Why is social media, as a technocratic approach to space, so inimical to both community and mental health? The very idea of social media platforms is technocratic, for they divorce our most basic human need, social connection, from any other human need. One’s life on social media is a wholly digital landscape designed by those with an interest in “engagement,” the scale of social interactions is on the order of millions, the currency of such interactions is quantitative counts of likes or reposts, the medium through which this interaction occurs is as private as technique can design it, and the intended purpose of the technology is the narrow goal, at least originally, of “social connection.” The great irony is that by designing a technique that has social connection as its primary goal and allowing that technique to subsume all other dimensions of human interaction, the product of engagement on such platforms is not social connection but utter loneliness. When an institution is designed for one narrowly defined end and attempts to pursue that end through every mechanism of technique, genuine community always becomes an impossibility. Mark Zuckerberg has gone so far as to declare that virtual reality offered through Meta may be “the most social platform.” However, because the very medium of social media operates by unilaterally technocratic mechanisms, the kind of community it forms is utterly false. It only makes sense, therefore, that the outcomes it produces are the opposite of genuine community—loneliness, anxiety, and depression.

Health Through the Community’s Eyes

Addressing loneliness and isolation is not a technical problem. Public health programs and civic initiatives to address loneliness that have experienced the most success tend to be those that create environments which foster great social connection, as opposed to directly addressing any individual behaviour or maladaptive social cognitions of any one lonely individual. The surgeon general’s report on loneliness and isolation touches on this idea in its description of a “culture of connection,” which acknowledges that “while formal programs and policies can be impactful, the informal practices of everyday life—the norms and culture of how we engage one another—significantly influence social connection.” Indeed, what the public health community often fails to realize is what Lewis identified so clearly: that friendship is an indirect good produced when genuinely achieving a different aim. Unlike housing or food, one cannot scale the provision of a discrete good called “social connection” that can be easily “referred to” for individuals in need of this service. Social connection, if it is the kind that genuinely leads to better health, cannot be easily packaged and delivered. As Nicholas Christakis and James Fowler write in their book Connected, “Social networks can be difficult to understand in part because they are difficult to manipulate. We cannot give you a friend the way we might give you a placebo.”

As I observed at the outset, it is en vogue to be on the side of community. But that does not mean it is easy. Indeed, nowadays an explicit posture against technocratic reach is perhaps the clearest opportunity to take a stand for community. As Wendell Berry writes, “There is no denying, of course, that ‘community’ ranks with ‘family,’ ‘our land,’ and ‘our beloved country’ as an icon of the public vocabulary; everybody is for it, and this means nothing.” It is easy to claim to be on the community’s side; it is much harder to resist the kind of technological development that has the displacement of community as one of its core outcomes, despite whatever efficiencies it may yield. Berry continues, “If individuals or groups have the temerity to oppose an actual item on the agenda of technological process because it will damage a community, the powers that be will think them guilty of luddism, sedition, and perhaps inanity.”

Rates of loneliness in the United States nearly doubled between 1990 and 2020. Such trends can only prompt one to consider what surveys will reveal in 2050 unless an alternative is clearly identified and championed. Public health professionals—and all those who take interest in the goods of friendship and social connection—must learn to work together to reanimate communal life, often by removing the technologies that have for too long prevented the opportunity for friendship.