H

How do we act in a reality we cannot name?

This question has become the haunting motif of my days. Everywhere I go, I hear a looping disorientation: spikes of urgency, sharp and vertiginous, followed by long stretches of quiet in which daily life hums along and the world seems, on its surface, fine. Especially in democracies grappling with their own fragility—pressed by rising populist revolts and their push for recognition, shadowed too by ecological distress that flares and fades from view—there’s a rhythm of crisis and forgetting that leaves many of us grasping for bearings reliable enough to make discernment, and the committed action that flows from it, possible.

The air is thick with world-historical questions of moral urgency, but they circle in a whirlpool of inconclusion. Is it time to draft a new Barmen Declaration? Is Trump evil, or just a narcissist with instincts honed for leverage? Are we witnessing the long-overdue judgment of a corrupted elite, or the uncoiling of something more ancient . . . and dark? How do we stay human with AI in our midst?

In swirls like these, not yet clarified by the onset of a widely shared catastrophe, the instinct is to search for precedent. We search for historical parallels to orient ourselves and discern the proper response: Is this 1930s Germany? Soviet Russia under Brezhnev? Latin America in the 1970s? Eastern Europe in the early nineties? We return to Orwell, Arendt, Bonhoeffer, and Huxley. We reach for the big words—“fascism,” “nationalism,” “authoritarianism,” “resistance”—each one, in my context, feeling increasingly credible. Warnings worth heeding.

But the more I listen across the layers of my own nation, the less confident I become in using these terms: each sketches part of today’s disturbed terrain but risks reducing the texture of a surprisingly resilient civil society to the fatalistic simplifications of political type. History, stubbornly, has a way of fusing old patterns into new arrangements, scrambling familiar scripts and morphing into something that tests—yet again—the human capacity to choose the highest good.

And so we are left with questions not just of perception but of judgment. At what point should one dissent, and how, and with whom? How does one form a conscience capable of choosing rightly when dark forces are on the rise? Can dissent do more than resist—can it bear the seeds of something new?

—

These are fraught questions for North American Christians, whose relationship to the word “dissident” has see-sawed in recent decades. For much of the twentieth century, to be a Christian dissident was to stand athwart totalizing power—power that, though configured differently regime to regime, bore a recognizable odour inside the nation: a false orthodoxy cloaked in righteousness, enforced through fear and the invisible violence of compliance.

We remember Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn and Irina Ratushinskaya, Václav Havel and Mária Wittner, Dietrich Bonhoeffer and Sophie Scholl, Óscar Romero and Dom Pedro Casaldáliga, Howard Thurman and Fannie Lou Hamer. The threats they faced differed in kind—some stood before tanks and trials, others against a tyranny of thought and sanctified perversions—but the calling was the same. To be a Christian dissident was to speak truths that pierced the atmospheric lie, to stand as a still point of eternal reference before a repressive machine intent on remaking the social order on its greedy, paranoid, or utopian terms.

Christians in the West simply do not agree on what constitutes totalizing power, nor which evils deserve resistance.

But for those shaped by forty years of culture war, the landscape feels unhelpfully diffuse. Christians in the West simply do not agree on what constitutes totalizing power, nor which evils deserve resistance. Our spiritual antennae are not tuned to the same frequencies. It’s not that the signs of danger are hidden, but that we do not read the signs in the same way.

This is the impasse that shaped the curatorial burden of this issue. My own hunger to explore this notion of “holy dissidence”—in dialogue with the older, more contested word of “remnant”—arose from a spiritual nausea I couldn’t shake in the early months of Trump 2.0. It wasn’t only the pace and pattern of institutional destruction that unsettled me; it was the witness of self-professing Christians seeming to applaud one rapacious spirit after another, sulfur seeping through the likes of alleged predator Pete Hegseth, open racist Stephen Miller, Christian nationalist Russell Vought, shadowed soul J.D. Vance.

With so many public servants I esteem and with whom I worship in Washington, DC—friends who have dedicated their lives to defending the widow and the orphan—it was wrenching to see their work not only gutted but also recast as subversive to the new order. It felt at times as though Jesus himself were on trial. “Who do you say that I am?”

By mid-February, I was inarticulate with anguish. If this is the moral atmosphere now sanctioned by vast swaths of those checking “Christian” at the ballot box—an atmosphere where right-wing ideology is bizarrely enforced with Soviet-style tactics—where, then, does one go? How does one speak? I found myself straining for language, searching for a word to capture the underground I sensed growing restless in our troubled Western context—a subterranean stirring of souls craving a pre-political space of gathering and ressourcement, where they might resist tyranny on the one hand and the corrosion of spiritual elitism on the other.

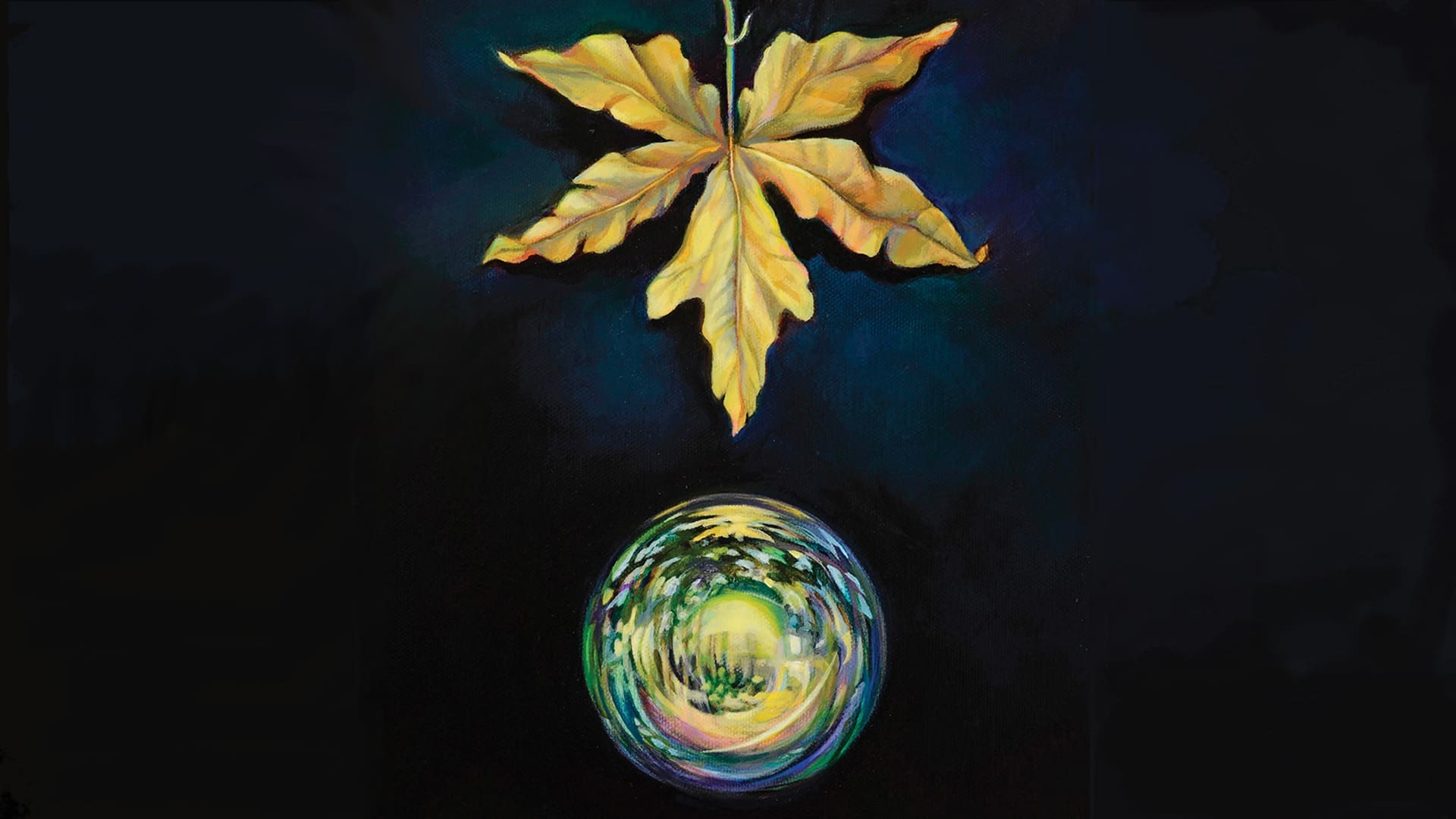

“It Will Not Pass Away” by Susan Savage, 2010

But what would such an underground look and sound like when the overground so aggressively lays claim to the same symbols? How do you fight not just a bad argument but a tone of voice and an ethos—what our tradition knows as principalities and powers?

Welcome to the “soft” turf beneath the hard headlines of this moment. What this issue offers is the beginnings of a searchlight for the shadowy catacombs where many of us find ourselves—not always able to explain how we arrived, only that the air above ground smells cheap, untrustworthy, and spiritually unsustainable. Our authors offer a series of dispatches from below: a diverse witness—past and present—drawn from those who have always refused, and still refuse, to mistake “Christian culture,” “Christian civilization,” or “Christian values” for Christ himself—refusing to bow to the idols and unrepented histories such phrases too often conceal.

I invite you to come with us into the flickering crypt. As we all try to speak and act within a hollowed-out stage of language, amid the deteriorating scaffolds of meaning that attend our (and every) hinge of history, it’s important to remember that truth still has a face. That face belongs to a person, Jesus of Nazareth, who beckons us into places where the disciplines of attention, silence, shared tables, and truth-telling can take root again. And it just may be underground that we will find him, and get clear, once more, on where he is going.