This past Christmas, my wife Joy and I hired my fourteen-year-old nephew to do some housecleaning and put up our Christmas tree. All was routine, when out of the blue, a loud crash reverberated through the walls. My nephew ran to the other room to see what it was before casually walking back out. Joy looked up and asked him, “What was it?” He answered nonchalantly, “Oh, something fell.” “Well did you pick it up?” Joy asked. “No,” he responded, “I wasn’t the one that made it fall.”

When it comes to the issue of race in America, there are many people who see the evidence of something fallen and broken, and their response is to look at it, turn around, and say, “I’m not to blame, so I’m not going to take any responsibility for it.” Others, upon awakening to the visible and less visible realities of inequity, quickly become overwhelmed. They recognize that the problems of race were created over a 350-year period before our government said, “It’s illegal to continue in this way.” They can only respond with the question, “What in the world can I do?”

Paralysis is understandable given that the racial hierarchies in our society were built through several centuries of legislation, regulations, and policies. These structural decisions effectively created a racialized caste system, one that endures to this day and affects our interpersonal relationships whether we want it to or not. The question is: How does one become a positive agent of change for a problem that is not just personal, but interpersonal, cultural, and structural?

Taking Ownership

The first step is to understand that while not one of us alive today is to be blamed for the racialized world in which we find ourselves, we do have a responsibility to clean up the mess we’ve inherited.

The second step is to understand that people form institutions and institutions form people. Any study of a successful social movement will find an early stage of organic growth. A gap will exist between what is and what ought to be, and at some intensified inflection point people will come together to solve the problem. What begins informally slowly but surely begins to solidify into a structure, which eventually demands a more formal set of systems, norms, rules, and roles. You might call this the three trimesters of institutional pregnancy.

An important task of the maturing person is to seek understanding of how the various institutions we are a part of have shaped us—both in their unique gifts and in their unique brokenness.

Since the Vietnam War, Americans across class, race, and ideological worldview have grown steadily distrustful toward institutions. The debate often focuses on trusted sources of authority, how much authority and responsibility a particular institution is given, or how much authority and responsibility we should give to individuals. Rarely do people recognize the dance between people forming institutions and institutions forming people.

The reality is that each of us is forming and being formed by a multitude of institutions at once: our family, our community, our faith community, our educational institutions, our place of work, our local, state, and national government. An important task of the maturing person is to seek understanding of how the various institutions we are a part of have shaped us—both in their unique gifts and in their unique brokenness. Whether we are to be blamed or not, there is always an invitation to take responsibility for transforming the institutions we are a part of into reconciling communities.

This leads us to the third step: to embrace the vision of your community becoming a reconciling community, and to learn and then implement the practices that bring this vision to life.

A community is a group of people linked by a common purpose and rhythm of life. In a reconciling community, the community acknowledges the depth of brokenness in our world and actively participates in God’s invitation to bring healing to the brokenness. The transformational journey to become a reconciling community and bring healing to our world must happen holistically.

We live in a day when too often people surround themselves in echo chambers of their own worldview. As I endeavour to work against this in my own life, I find myself listening and dialoguing with people on both sides of the aisle. Although there is a lot of attention being given these days to conservative fundamentalists, I’ve discovered that there are also liberal fundamentalists and that both increasingly share a similar character profile. Each party sees the other as the enemy. Rarely do they self-examine as rigorously as they critique their perceived opposition.

For those who approach this work as Christians, it’s important to recognize that the Christian understanding of transformation happens from the inside out, not the outside in. The Christian perspective acknowledges that there is sin and brokenness “out there” while also acknowledging its presence inside each and every one of us. The practice of self-examination paired with the prayers and practices of transformation allow us to become the kind of people who can transform our community and institutions in a positive and productive way.

I am a part of a Christian community in my neighbourhood in Richmond, Virginia. We live, work, and worship together in a one-and-a-half-mile radius. We are committed to pursuing the work of reconciliation over decades. As pilgrims, we journey together through the mountains and valleys, twists and turns that are inherently a part of engaging in reconciliatory practices across differences of race, class, and culture. Hope is gradually being realized in this container of commitment and bounded geography, but we are not immune to national news stories needling their way in and reshaping internal dynamics.

It was the summer of 2013 when the story of Trayvon Martin started to dominate the national news cycle. The case was in Florida, where a “stand your ground” law allowed you to kill a person if you felt scared or feared for your life. George Zimmerman had been a self-appointed neighbourhood watchman, saw Travon walking down the street one evening in early 2012, thought he looked “suspicious,” and fatally shot him in the chest.

The verdict of George Zimmerman’s acquittal came out on a Saturday night. The next morning, the atmosphere in our Sunday worship service was thick with grief. For those in our community who were more conservative and supporters of the Second Amendment, they saw this story as political. For others in our community who had experienced the unfounded fear of their body because of the colour of their skin, they saw this event as a pastoral concern. In a diverse church with little shared experience around the circumstances that had faced Trayvon, finding common ground was near impossible.

Earlier that same summer, our church had focused on the lament psalms, inspiring several in the congregation to write a song called “Purge Me.” When Zimmerman’s verdict came out, it seemed an appropriate time to debut it. After the preacher preached, the interns performed the song, and when they finished singing, a silence fell over the church. After some minutes, a wailing of tears broke out, followed by a chorus of congregational crying. The crying turned into prayer, and in the midst of one of the prayers I heard a blonde-haired, blue-eyed white sister pray in the midst of tears. It was that tearful prayer that became the balm to my wounded soul from multiple humiliating police stops and drug searches that I had experienced as a black man who has never touched drugs in my life. That day as a church, we didn’t debate politics or the legitimacy of our Christianity because of our political views. That day we practiced being a reconciling community by doing what the apostle Paul says in Romans 12:15, to “mourn with those who mourn.” As a result I received the kind of healing I didn’t even know I needed.

Removing the Splinters

As Christians, whether conservative, moderate, liberal, or progressive, our antennae should go up when we hear someone say, “The problem is those people over there!” While this may be true at some level, and while Christian theology and practice make room for bringing correction to another person, in Jesus’s most famous sermon, he encourages his followers to examine oneself before one tries to correct another person.

Reconciliation is spiritual formation.

“Why do you look at the speck of sawdust in your brother’s eye and pay no attention to the plank in your own eye?” Jesus asks in Matthew 7. “How can you say to your brother, ‘Let me take the speck out of your eye,’ when all the time there is a plank in your own eye? You hypocrite, first take the plank out of your own eye, and then you will see clearly to remove the speck from your brother’s eye.”

Four years into our marriage, Joy and I found ourselves in a bad place and went to see a marriage therapist. I didn’t think we needed a lot of work; I fully expected the therapist to agree with all of the things I thought were wrong. I assumed that with a little correction “for Joy,” we would be on the way to a thriving marriage. Of course, my self-absorption soon crashed into reality. It gradually dawned on me that the only way for me to transform my marriage was to transform myself, a realization that has to be the starting block if reconciliation (within a family, a neighbourhood, a place of worship, an educational institution, a place of work, a government) is to be realized.

Some years ago, I founded an organization called Arrabon, which equips institutions and individuals with the five pillars of building a reconciling community. The first pillar is to understand that reconciliation is spiritual formation.

When it comes to the area of race, I understand the hesitancy many feel about using the framework of “reconciliation.” There is a presupposition behind the word which suggests that in order to engage in reconciliation there has to be (1) an established relationship and (2) a fracture in that relationship creating the need for reconciliation. One person might say, “Hey, I haven’t done anything racist, so therefore I don’t have anything to reconcile.” Another person, though they understand the systemic and social nature of race relations, says, “Europeans, indigenous people, and Africans were never equal in their relationship with one another here in the United States, so we don’t want to reconcile that relationship. The most we can do is engage conciliation.”

Conflict resolution is a basic human need.

If the word “reconciliation” is being defined within that framework, then yes, we don’t want to use the word. At Arrabon, we define reconciliation within the biblical narrative of Genesis 1—the world was whole, good, beautiful, and diverse, but brokenness entered the world, as we read in Genesis 3, and God has been in the work of reconciling all things ever since. Understanding reconciliation in that framework allows us to see that conflict resolution is a basic human need. It helps us to understand that God is always inviting humanity to partner with Jesus in the reconciling of all things. Hopefully we are agents of healing to others in that invitation, but often, when we receive the invitation from God to engage the brokenness of our world in a transformative way from the inside out, we are formed spiritually in a way that forms us more in the likeness of Christ.

Looking Outward with Curiosity

The second pillar for a reconciling community is to engage in the practice of increasing your cultural intelligence. Culture is a shared pattern of beliefs, values, assumptions, and behaviours that distinguish one group from another. Cultural intelligence is the skill to relate and work effectively in culturally diverse situations. As our country becomes more and more diverse, one’s capacity to engage gracefully and humbly with those from different backgrounds becomes paramount. Too often people settle for talking past one another, doubling down on their preferred way of communicating instead of taking a moment to pause and strategize on how to be more effective in communicating across differences. Increasing your cultural intelligence will help you increase the cultural intelligence of the institutions of which you are part.

The third pillar is learning the many different narratives that one community—your community—holds. A person’s demographics has a significant influence on his or her experiences. People can witness the same set of events, recall the same set of facts, but have a completely different perspective of a situation based on their demographics. A person with economic resources has a very different set of experiences from one who is economically poor. Men and women have different experiences because of gender dynamics. A person of one racial category or ethnicity has different experiences from another because of what certain racial and ethnic categories mean in certain scenarios. Learning to lean in and hear the different narratives of your community increases empathy, understanding, and trust.

Having laid the foundation of these three pillars, participating in cross-cultural collaboration becomes a lot easier (the fourth pillar). Too often collaborations fail because of a lack of commitment to work through conflict or failure to put in the work to understand different expressions or viewpoints. Creativity and innovation emerge when people are committed to doing the hard but rewarding work of participating in cross-cultural collaboration. Homogeneity can yield efficiency, yes, but a lack of diversity often leads to monotony and eventual stagnation. We are in a desperate time today. We need innovation. We need people from different points of view working together to solve intractable conflicts and problems 350 years in the making.

This leads us to our fifth pillar—engaging in reconciling culture-making. We are here today because of the culture that was made yesterday. If we want to see something different tomorrow, we have to create new culture today. Imagination is the difference between what is and what could be. We need more people and institutions willing to stare at what is broken, and, instead of casting about and asking, “Who is to blame?” turn to one another and ask, “What can we do to make this better?”

We can and should sharpen our tools. Being grounded in spiritual formation and hopeful imagination in a collaborative community is the foundation to creating a future worth fighting for.

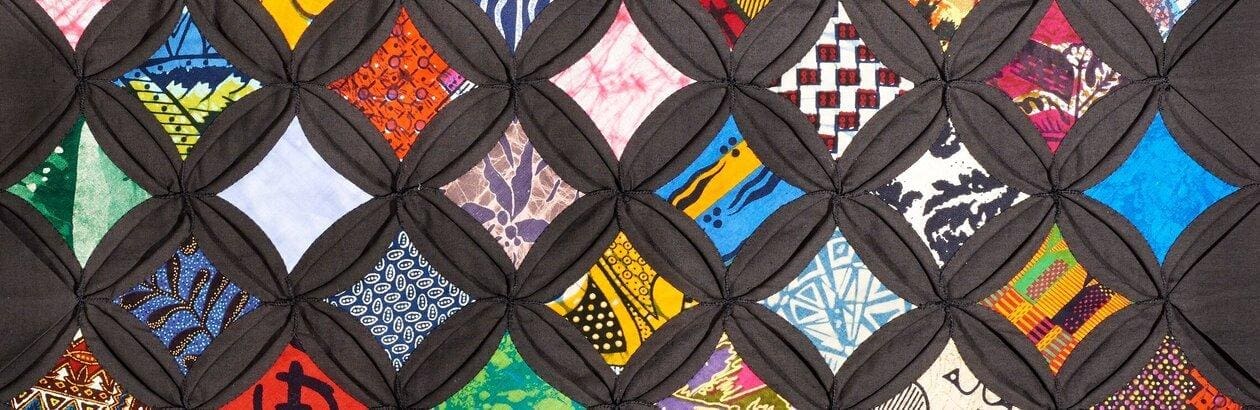

Image: Cathedral Window Quilt by Viola Canady, 1992. Anacostia Community Museum Collection, The Smithsonian Institution.