I get it. Let me just start there: I totally get it.

I completely understand why a generation of Christians feels like conservative Protestantism has been keeping a secret from them: that the Bible talks about justice. As someone raised during the height of the culture wars and witness to often-ugly public vehemence, I understand the bitterness and disappointment and the desire to distance oneself from all of it. Those in authority—parents, pastors, maybe even professors—hoodwinked us into a narrow fixation on personal salvation or a very narrow set of public concerns that were portrayed as God’s favourite partisan interests.

It can be a startling revelation to learn that the ascended Lord is not only concerned with forensic justification and “law and order” in the public realm, but is equally concerned with the widows, orphans, and immigrants among us—that “the poor” to whom Jesus promised liberation are not just the poor “in spirit” but those who are really poor—those who don’t have enough money and lack the power required to master the systems that oppress them. We might still be reeling—and just a little bit embarrassed—from having woken up to the realities of systemic racism and now find it hard to un-see the overwhelming whiteness of our Christian milieu and the public face of “conservative” Christianity. This is especially true when many of those public Christian voices constantly ally themselves with the vested interests of what looks a new plutocracy. It’s hard to square all of this with the Jesus we meet in the Gospels.

On top of that, those Christians who trumpeted their “conservatism” just seemed so, well, angry. Their demeanour felt more like reactionary warfare than charitable hospitality. In many ways, their moral crusades demonized the people we went to college with and the causes our friends care about. What they decried as ominous threats and abstract menaces had names and faces for us: they were our classmates, our teammates, our roommates—and we liked them, loved them. For a host of reasons, then, we shouldn’t be surprised that the default posture for a new generation is leftish, perhaps without even realizing it.

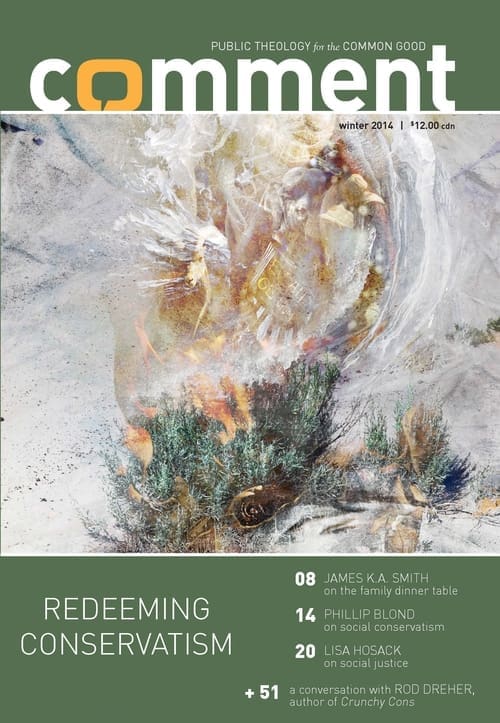

So who in their right minds would try to redeem “conservatism” today? Well, we’d like to give it a try.

If you can’t imagine anything good coming out of conservatism, this issue is for you. My hope is you’ll discover, first, that conservatism is not what you thought it was. What we’re trying to redeem is a disposition, not a dogma. We commend to you a posture, not a platform. Second, I hope when you encounter this conservative disposition, you might be surprised to find this names a sensibility you already share. Our goal is to start a conversation that “redeems” conservatism precisely by deconstructing what we tend to identify with it.

This isn’t a rewind project. This is not a call to turn back the clock to recover a fabled golden past, or to return to the Garden of some pre-1960s paradise. Such nostalgic idylls are what the poet W.H. Auden called “Arcadianism”—the illusion that we can simply return to our lost Edenic home, forgetting, as Alan Jacobs points out, that weaponized angels prevent such simplistic re-entry.

Conservatism, as we mean it, is not a recovery project; it’s a preservation project. The point isn’t simply to defend the status quo; the point is to preserve traditions, institutions, and practices only because—and only when—they foster flourishing and societal health. This is also why we need to rethink a rather uncritical embrace of progressivism: what looks like progress and liberation might actually be burning down the structures and scaffolding needed for the poor and vulnerable and marginalized to thrive and prosper. If you’re a progressive, every fence looks like a corral. But those same fences might also provide protection, so losing them isn’t always liberation—it can also expose us to new threats. In this issue, Brian Dijkema considers an example: while liberal elites demolish longstanding sexual norms, they nonetheless continue to live by them, and it is the poor and vulnerable who bear the brunt of such “progress.”

In a recent National Affairs essay, “The Conservative Governing Disposition,” Philip Wallach and Justus Myers emphasize that conservatism is not a doctrine or even a defined set of positions; it is a disposition, a temperament. “When existing institutional structures are incompatible with liberty or justice,” for example, “conserving them is rightly seen as illiberal or unjust. Although conservatism is centrally concerned with mitigating the disruptive effects of certain kinds of social changes, it does not aspire to preserve the status quo just as it is.” Conservatism isn’t about protecting the status quo; it’s about what Philip Blond calls social conservation, preserving human beings and their relationships so that they can become what they were made to be. What’s dangerous—and increasingly disastrous—about progressivism is precisely its refusal to recognize something like human nature.

Wallach and Myers describe the conservative temperament as its own kind of hopefulness. Since “conservatives seek to conserve and improve what is good in their societies, acting as responsible stewards of their social inheritance,” they address problems “by building on the best of what they have.” So conservatism is actually rooted in a sense that there is something worth conserving. Indeed, “there is something inherently sunny about conservatism, and it best suits those who believe that their own societies are complex, flawed, but ultimately worthy of appreciation.”

Consider this issue an invitation to a hopeful project of social conservation for the common good. Indeed, we might put it even more starkly: if you care about justice, you might want to be a conservative.

Such conservatism is not an against-ism. The sort of social conservationism we’re advocating isn’t reactionary or defensive; it is constructive and forward-looking and can be, at times, prophetic. Roger Scruton succinctly captures the point in his book, How To Be A Conservative. “Conservatism starts from a sentiment that all mature people can readily share: the sentiment that good things are easily destroyed, but not easily created.” In the name of justice, we too often get knee-jerk progressivism that erodes and destroys some of the best gifts handed down to us for tackling injustice. “The work of destruction,” Scruton observes, “is quick, easy, and exhilarating; the work of creation is slow, laborious, and dull.” But such creative conserving work is germane to securing the goods necessary for the poor to prosper.

“It is not about what we have lost,” Scruton points out, “but about what we have retained, and how to hold onto it.” This is the sort of progressive—or better, prophetic—conservatism to which Paul exhorts the Thessalonians: “Do not despise prophecies, but test everything; hold fast to what is good” (1 Thessalonians 5:20-21). A “redeemed” conservatism is a desire and willingness to hold fast to what is good for the sake of the shared goods we call “society.”

Of course, “Hold fast!” is also a nautical imperative in the midst of storms: secure the rigging, grab hold, and ride it out. In this sense, we might think of the church as an ark in the midst of stormy cultural seas—a nourishing, preserving centre from which we are sent as emissaries of both conserving conviction and audacious hope. In our interview in this issue, Rod Dreher calls this “the Benedict Option”: committing ourselves to faith communities that are preserving sanctuaries of ancient biblical wisdom, not so we can hide from culture or retreat to some nostalgic past, but precisely so we can then be salt and light.

As Pope Benedict once testified, the Lord’s Table is “the school of charity and solidarity that should make us more attentive to the many people who struggle to procure their daily bread. He who eats of the bread of Christ cannot remain indifferent before those, who also in our day, are deprived of their daily bread.” When passion for justice is intertwined with “updated” faith, we merely get assimilated progressivism. In the years to come, it might be the “conservative” church that looks revolutionary.