As I write, my neighbourhood of Sandtown is in mourning from riots, looting, and violence that tore apart central streets in Baltimore. But we aren’t just sitting around gnashing our teeth on social media. Clean-up efforts are happening across the city. City and community leaders and youth (who have been restricted by a daytime curfew) are in dialogue, trying to discuss and process recent events. At the heart of these discussions are two questions: What can, and what should we do to overcome the deep fractures that have divided our city? And how can Baltimore, which has its own unique history of dividing lines fostering inequality, be made whole?

There is still a strong undercurrent of thought presupposing that if people in my neighbourhood would simply pull their pants up, stop injecting drugs, keep their kids in line, and get back to work we’d all be better off. I’m happy to report to anyone too scared to hear this for themselves that this sentiment is repeated every time I stand in line at my local post office, so I suspect that those who are walking around with saggy pants have heard it before too. They have almost certainly said it themselves. If simply pronouncing such self-evident truths could have fixed my neighbourhood, it would have by now. Every person is responsible for their own actions before God and their neighbours: This is a truism.

But what many armchair commentators remarking on Freddie Gray’s arrest record seem to miss is the scarcity of resources and mediating institutions necessary to connect anyone’s desire for improvement to the supports that might actually help accomplish it. Willpower is not inherited like a gene or handed out like food stamps. It’s cultivated like a garden. But Sandtown has experienced decades of scorched-earth tactics designed to cripple the community’s wellbeing, followed by decades of policies that extracted the best plants from the garden while neglecting the soil. Welfare payments and public housing keep people alive through crises, but they’re too small and too inflexible to allow people to own anything that they can capitalize on. Cultural decline, then, is a consequence of economic devastation even as much as it is a contributor to it.

The economic and often physical violence done to black communities over the years still affects Baltimore today. Concentrated pockets of poverty can be found in neighbourhoods that were “redlined” decades ago. And the city still pours money into vanity projects like casinos that perpetuate poverty by directing limited money away from historically neglected neighbourhoods.

It isn’t just a matter of what happened in the past, though. Neighbourhoods like the one my family and I have lived in for the past several years have suffered from ongoing police brutality that, combined with the day-to-day violence associated with drug dealing, creates an atmosphere of fear and mutual distrust. Poor schools, minimal job prospects, drug addiction, substandard housing, and mass incarceration ensure that new generations are no more equipped than the last to deal with the social ills that our neighbourhood faces. The people who rioted and looted experience the police and city government as a fickle cabal. Why are we surprised that they would disrespect the law when the law has disrespected them for so many years? What has happened in Baltimore cannot be defined simply as protests turning violent; it is anger without direction lashing out at the nearest pane of glass.

One of the uncomfortable facts of human nature is that individual virtues alone cannot restrain the sorts of terrible urges in which people indulged in Baltimore. Communal vice of this sort is restrained as much by our social contracts and the moral codes that communities create through social pressures and judgments. If The Wire showed us anything, it was that the official institutions that people deal with every day can be just as corrupt and untrustworthy as the gangs that roam the streets. Unfortunately, the result is that it becomes natural to take what you can get if chaos is going on around you and to respond with rage to the murder of your neighbour by agents of the state. As a young man from Sandtown recently said in a great PBS interview, “I’d rather call my neighbour than the person being paid to protect us.”

But The Wire also missed something. It neglected to take seriously the strengths and weaknesses of the smaller institutions that help people channel their anger and frustration into positive change. Yes, we saw the boxing ring in Season 3 and the after-school program in Season 4, but their presence in the story seemed primarily to be plot devices not fulcrums of change.

We have to understand that part of what makes change so hard for so many people who are trapped in systemic and personal destruction is the scarcity of communities that are necessary for moral formation.

The intermediary institutions—churches, schools, hospitals, businesses, neighbourhood organizations, or even the local offices of government programs—are given short shrift in our discussions. Small but strong institutions have grown up in these places to help people participate in moral and civic formation. But they remain stunted dwarfs because of the police and the gangs and because money is siphoned out of the community as people have to shop and work elsewhere.

In Praise of Minor Leaders

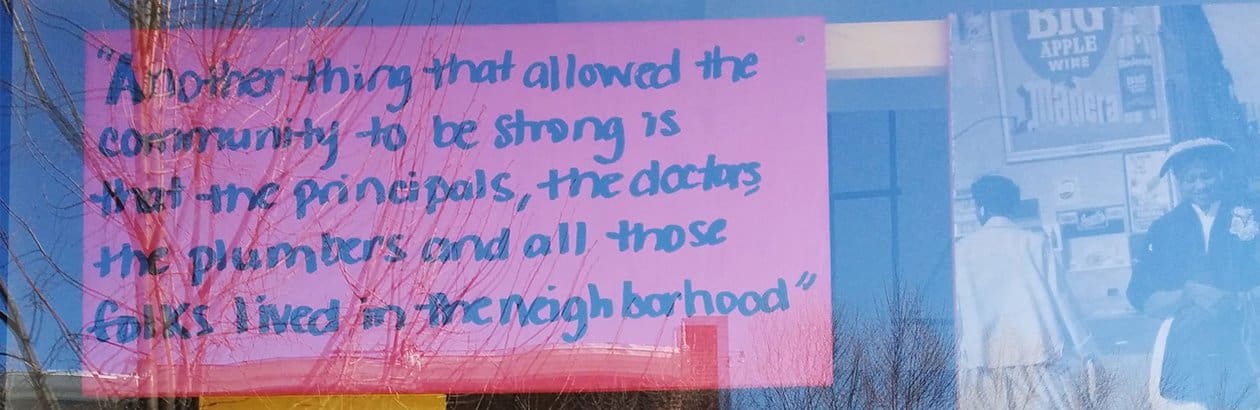

One of the opinions I’ve heard from people who grew up in my neighbourhood and lived through the Civil Rights era is that their community used to be more tightly knit and healthier, but that the end of segregation meant that some of the best citizens moved out. Once they were free to go, the doctors, teachers, and lawyers left with their families.

To this day it is viewed as a “success” if one can get their family out to a house in the county. No one thinks that going back to segregation is good, yet it was better for the neighbourhood in general when people of different classes lived more closely together and looked out for one another. This statement obviously makes people uncomfortable, but it illuminates how powerful conceptions of community are and how destructive it is when there is no incentive for people who are privileged to stay in a place that needs them to be neighbours.

Those who have stayed when they could have left do not particularly resent those who have “gotten out,” but they are quite frequently exhausted by the work of trying to support those who have not been able to do so. Every community needs a phalanx of people who take minor leadership roles and simply care for their neighbours. They stand between the established leaders and help mediate what is good and worthwhile to the vulnerable while keeping predators from within and without in check. Without these folks to stand in the middle, though, more people can become vulnerable or predatory.

While white people like me who grew up in the more affluent counties and moved into Sandtown are the lead in news stories, the people truly worth applauding are those who could have left but stayed, or those who moved from a slightly nicer neighbourhood to a worse one. These folks are my friends, my mentors, and my leaders. They are the ones who drove around the neighbourhood as the riots went on to make sure everyone they knew was safe. One of my neighbours, whom I’ve worked with for a number of years through our church, told me about how she was criticized by her family for choosing to live in Sandtown when she moved in during the 90’s. Her response then (and now) was: “If everyone who can get out leaves, who will rebuild?”

Obviously people with resources moving to areas of need is not the only solution, but it is part of the solution because our ability to empathize and learn from—and perhaps eventually help)—people who are struggling is directly correlated to our proximity to them. There are some people who have served my neighbourhood for many years without moving in, but they’re here often enough that they’ve exposed themselves to the risk of loss. Whether that’s sacrificing time and energy wasted on a project that didn’t play out, getting their car broken into while they worked down the block, or feeling the pain of people they would otherwise be insulated against caring for by cultural forces that cast black people in the inner city as “other.”

All Hands on Deck

Most essays like this one have ended with “I don’t know how to fix it.” While I have only spent five years here, my neighbours have some pretty clear ideas. Plant some gardens to employ people coming home from prison. Help fathers learn to be providers and role models. Teach kids art. Advocate for better policing. Teach and tutor kids. Renovate vacant houses or build new ones. All of this has been paired with preaching and teaching through churches, the institutions that have stayed and done so much to help people weather the storms of the last several decades. We understand that personal renewal has to be paired with systemic change, which is why the Christian Community Development Association (of which our churches are members) stands on the principles of relocation, reconciliation, and redistribution. However, in the fight against the destruction caused by poverty and violence, we need more hands on deck and more policy decisions that incentivize neighbourliness. We need more people living here and loving one another matched by larger efforts to reinvest in the community. We also need capital to tear down or repair vacant buildings, start businesses, and provide jobs to the thousands of men who want to work but can’t find any work beyond dealing drugs.

In the Civil Rights era, we had the theological resources to address the injustices that people were suffering. People with social, cultural, and economic power were simply afraid of what would happen when the barriers built by centuries of racism were torn down and the hurting people on the other side were allowed to mingle freely. What we face now is a similar (though not identical) circumstance wherein we have physical barriers and distance between those who have material resources and social capital and those who need both in order to climb out of poverty. The Gospel has the potential to be the gravitational center for hope. Churches in places like Sandtown are abundant and many would welcome people who are willing to take the time to sit and listen.

This is not simply a matter of the rich and powerful sacrificing for the sake of people in poor urban communities. It is also not a matter of poor urban communities since many rural places and even many suburban places need more good neighbours working with local churches. But we need to come to terms with the fact that exercising ourselves in service and challenging ourselves by frequent, intimate exposure to another culture’s expression of faith is a means of discipleship. It also a testimony to the watching world that Christ’s sufficiency transcends our cultural impetus to protect ourselves from “those kinds of people.” We don’t need an elite corps of radical Christians, we need faithful believers with power and privilege to simply spread out and join with brothers and sisters who don’t have the same resources we do.

What will hold us together is what has held the people in my neighbourhood together for so many years: loving one another and worshipping God. What will inculcate these values in people who lack them are institutions reinforced by people with privilege who come in to listen to and serve under local leaders. What will keep these institutions from drowning in a sea of government neglect and street-level violence is accountability and transparency from civil servants. What will transform us is the hope that God’s Kingdom is coming. We will follow the Holy Spirit to the front lines of His advance, and continue the slow work of restoration with the builders who have been there for decades.