In 1976 the American bicentennial lit fires, patriotic fires, all over the country. In elaborate displays of pageantry tall ships sailed into American harbours from around the world. Baseball teams wore old-fashioned pillbox caps. The US mint flooded the market with ceremonial coins, emblazoned with revolutionary symbols. Queen Elizabeth even made a state visit in the first week of July, bequeathing to the nation a Bicentennial Bell while visiting Philadelphia. Have no doubt: Uncle Sam was riding high.

But the fires burning among America’s historians were of a distinctively warm variety. Freedom, that emblematic American ideal, had in their eyes been refined by fire over the previous decade: the fires of protest, sacrifice, and martyrdom. As the bicentennial arrived historians greeted it with stories that sizzled and cracked with a new—a renewed—vision of freedom for their country. And these were not quite the same stories that the American Revolution Bicentennial Commission had prepared for the occasion.

If the past never changes, history always does. Those who render the past always find new ways into it, with eyes conditioned by diverging experiences and shifting beliefs. If you can’t step into the same stream twice, you certainly can’t enter the past today just as historians did fifty years ago. The unfolding story, the human story, juts along in mysterious ways. Its ending looks different every day. And so does its history, for those with eyes to see. The American historians of the 1970s had such eyes: eyes trained by moral purpose and ethical hope. Having witnessed the brutal assassinations of Medgar Evers and Martin Luther King and more, having themselves marched and fought and (in some cases) bled, they proved incapable of recounting the stories—the conventional stories—they believed had helped to underwrite the ignominy of the American present. They had, they were convinced, truer stories to tell.

John Blassingame’s path-breaking book of 1972, The Slave Community: Plantation Life in the Antebellum South, archly revealed the emerging narrative shape. With theoretical daring inspired by hope, Blassingame discovered evidence of solidarity among slaves, rather than the atomizing degradation historians were then tending to see. And this was solidarity that yielded robust cultural expression: communal freedom in the face of subjugation. Three years later Eugene Genovese won the Bancroft Prize with his addition to this new freedom literature. In Roll, Jordon, Roll: The World the Slaves Made he, with yet more sophistication, thrust freedom to the fore by rendering the slave owners not the strong but the weak, the victims of self-inflicted psychic injury due to their embrace of slavery. And the slaves, in Genovese’s account, had achieved a measure of real freedom through acts of resistance, often rooted in religion. The Southern situation was inherently volatile in Genovese’s telling, the yearning for freedom destabilizing any efforts to kill it off. A new American story was spreading fast.

One more remarkable book from this era bears mention: Edmund Morgan’s American Slavery, American Freedom: The Ordeal of Colonial Virginia, published in 1975. The glories of the nation’s founding have rarely suffered a more devastating attack. With panoramic research and powerful prose Morgan detailed what can only be called the moral collapse of Virginia’s colonizing endeavour. It was only slavery, he showed, that had finally made it possible for the colony to gain political stability after decades of class conflict. It was slavery, further, that generated the economic prosperity that grounded the audacious attempt at political independence. Most troublingly, perhaps, it was slavery that furnished the everyday example to slave owners like Washington and Jefferson of exactly what oppression looked like. As Britain bore down, America’s slave owners witnessed—every time they looked out their windows—how humiliating powerlessness was. They would not be slaves.

No slavery, no freedom: this was Morgan’s claim. It was a stomach-turning message for America’s cheery bicentennial patriots. Or at least the historical profession hoped it would be: Morgan’s book won the profession’s Francis Parkman Prize and the Albert J. Beveridge Award. Clearly, these historians believed that Americans needed to remember their past differently. Gauzy and glib notions of American greatness must be shot down. Pious paeans to revolutionary geniuses must be silenced. In their place must come a truer story, corrected by better thinking, by sharper perception, by purer hearts.

These authors, in sum, wrote with spiritual admonition in view—if by spiritual we mean that which affects and directs the moral compass of human beings, the everyday orientation by which we navigate our jobs, our homes, our friendships, our minds. They were after education: the formation of better citizens and neighbours and professionals and colleagues and spouses. They wanted us to reencounter the past in hope of a better now.

This was revision with a vengeance—a belated vengeance, that is, or at least retrospective justice, if only in the retelling. Through such genesis accounts Americans might glimpse who they truly were. Revealing the snake in the garden would go a lot further toward explaining the actual history of the nation than the Edenic fantasies of yesteryear.

The church of American liberalism

For a profession that had long prided itself on objectivity, on neutral social-scientific observation, these books pulsed with unabashed moral energy, energy intended to imbue a polity with life. The researches of these historians had revealed what their own experiences as citizens had as well: that the reality of history requires an ethic of some kind, lest shame, defeat, and devastation follow. Whatever pretensions of secularity they may have held, they knew that even secularity must not preclude morality. And their work inferred as well the necessity of a common morality embraced and defended by a people. Their people.

In short, the vital elements of religion— civil religion—underpinned their project: a common creed, a holy vision, a corporate form. This American faith sponsored and enflamed their intellectual activism, their ardent efforts at moral reform. Chesterton’s quip that the United States is a “nation with the soul of a church” yet illumines, and the historical revisionism of the 1970s reveals at least one of the nation’s reinvigorated factions. Call it the first church of American liberalism, founded by enlightened philosophes and consecrated in the recurring battles for equality.

It’s not a coincidence that at the same moment Morgan was beginning work on American Slavery, American Freedom, Martin Luther King Jr. was declaring from a Birmingham prison in 1963 that African Americans would “win our freedom because the sacred heritage of our nation and the eternal will of God are embodied in our echoing demands.” Hearing such words, historians like Morgan set out to fulfill the prophecy King had made at the end of that historic letter: “One day the South will know that when these disinherited children of God sat down at lunch counters, they were in reality standing up for what is best in the American dream and for the most sacred values in our Judeao-Christian heritage, thereby bringing our nation back to those great wells of democracy which were dug deep by the founding fathers in their formulation of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence.” Morgan the historian had heard King the preacher. His duty was to take the people closer to King’s great dream, by way of the past.

Although race relations in America remain, it goes without saying, fraught, it’s worth pointing out that every January the nation officially pauses to commemorate the birth of King—the only figure born in the twentieth century we celebrate in this fashion. Critics scoff that we’ve merely replaced one pious vision of America with another—from heroic narratives of a master class to heroic narratives of oppressed classes. But the deeper story is a polity’s ongoing revision of collective memory, its canvassing of the past with longing eyes: eyes in search of a truth that leads not to despair or complacency but to hope.

Are not race relations in this troubled nation, whatever their failings, better for it?

The view from elsewhere

I turned ten in the year of the bicentennial. A cross-country “Wagon Train Pilgrimage” processed past our house in the city of Lancaster, Pennsylvania, heading toward Philadelphia. At Vacation Bible School we chanted patriotic songs by morning and visited historic sites by afternoon. My sister claims that I set up a polling booth in our house that November, requiring that everyone—including the college students who lived with us—vote. She also insists I plumped for the Republican candidate, Gerald Ford.

I myself remember no political discussions in our household, though tales of the military were always near. My dad and two of his siblings had been in the service; one of my mother’s brothers had done a tour in Vietnam, mailing us reel-to-reel tapes with bombs sounding in the background. I was mystified by the hippies and amazed when one summer day my clean-cut dad abandoned his wet look and started to use a blow drier, which matched the ubiquitous leisure suit a lot better, I suppose. It was a puzzling time to be a kid, especially a kid growing up in a seriously evangelical family.

But there was no doubt—its presence was everywhere—that we were growing up in a country. It was a womb, a matrix, a matria, if you will. The disputes of the day—the anxieties, the anguish, the anger—only make sense in this light. When in his searing 1963 epistle The Fire Next Time James Baldwin insisted on referring to the blind oppressing whites as his “countrymen,” he meant it. The “single garment of destiny” of which King eloquently spoke yet wrapped itself around us. I, at least, could feel its comforting touch. If we were not one, we were at least still convinced we should be.

But in July of 1980 my family moved to Brazil, where my parents would spend the next three decades planting churches. One of my uncles, who had been an Air Force sergeant, sent us kids to Brazil in gold T-shirts that announced that we were “Americans and Proud of It,” with a fierce eagle wrapped in an American flag. We arrived in Brazil with that pride, to be sure, and it never dissipated. In fact, in some ways it intensified. To be an American in 1980s Brazil was to be a mini celebrity, at least among ordinary folk. That was hard for a teenage boy not to like.

But this new country—which, too, was very much aware of itself as a country—had charms of its own. It quickly drew us into its embrace. It wasn’t long before I had abandoned bat and ball for futebol, and was trying to learn a language that was the obvious passageway into mystery

The culture was buoyant, the land breathtaking, the society shaky, the politics dark. Who didn’t like the food? Who wasn’t troubled by the poverty? And who didn’t feel at least some fear in the face of the nation’s governance? Even in our little international school there hung several official portraits of Brazil’s current president, João Figueiredo, the last leader of the military dictatorship that had seized power in 1964, stepping aside only in 1985. He was a general first, one simply knew, and a president second. Whatever he was, he certainly didn’t feel like my president.

Years later, as in graduate school I began to study Brazil’s history, I came to grasp more fully its particular ordeal. I began to see that, as in America, its people, with a kind of religious verve, had taken up the task of scouring the past on a quest for answers, in search of hope.

Its ordeal was so different and yet similar to America’s. Brazil’s European founders had slaughtered its indigenous peoples too. They had also disfigured the lives of millions of Africans in their quest for power and wealth. But unlike the United States, Brazil had no tradition of revolutionary heroics in a dramatic war for independence, and few liberating ideals with which to console (or blind) itself in the face of its dark past. In Brazil’s story of independence, the Portuguese crown, chased out of Iberia by Napoleon, simply moved from Portugal to Rio in 1808. Fourteen years later Portugal and Brazil amicably separated, and the king’s son stayed behind in Brazil to rule a constitutional monarchy that lasted through most of the century. And this monarchy accomplished socially what it had intended: In the words of the historian John Chasteen, it propped up “the social hierarchy that kept the slave-owning elite in charge.”

The fact that foundational texts in Brazil’s literary canon are preoccupied with the destructive effects of this longstanding hierarchy says much about its heavy presence in the national soul. In 1865 José de Alencar, seeking to illumine the mythic, tainted origins of the Brazilian people, published the novel Iracema, an allegorical tale of a tragic romance between Iracema, the beautiful daughter of a tribe’s spiritual guide, and a Portuguese soldier named Martim. The narrative’s insistent march toward the death of the love-starved girl, who even after their marriage could never fully win the heart of her European husband, makes of their motherless son the first Brazilian child. This is not a story of moral triumph. Rather, it seeks a way to make sense of pained longing and persisting alienation.

Still, Brazil’s elites ingested the conceit of Progress as fully as any other cohort of nineteenth-century Westerners, viewing the subjugated peoples as inferior in all ways that mattered and so destined for a dwindling, decaying end, at white hands if necessary. Among them was a writer named Euclides da Cunha, whose Os Sertões, published in 1902 (and translated as Backlands: The Canudos Campaign), was his unparalleled account of the nascent Brazilian republic’s suppression of a rebellion in the backcountry of the state of Bahia.

As the monarchy was passing into history, tens of thousands of Bahia’s poorest—and darkest—had in the 1890s converged to form Canudos, a centre of resistance to the modernizing republic, following a charismatic religious figure named Antônio Conselheiro. But the republic could no more tolerate such resistance than Virginia’s English could live with Indian scorn. And as Virginia’s indigenous peoples had centuries before, the backlanders of Bahia proved wily, brave, determined—and, shockingly, victorious, at least in the face of the first three campaigns. For the fourth an incredulous da Cunha accompanied the army, covering the final battle for a São Paulo newspaper.

This time the republic’s troops, rolling out the latest artillery in ruthless fashion, finally destroyed the city, at the cost of at least fifteen thousand lives. But da Cunha’s narrative, brilliantly expansive in scope, records his remarkable shift in perception, even in consciousness, as the campaign moved toward its brutal end. He, a modern intellectual (a Comtean positivist, in fact) who in the early passages of the book fully supports the “mission” of forcing “these rude and backward fellow citizens into the mainstream of modern life and into the life of the country,” finds himself stunned by their character, their courage, their knowledge. He comes to see them as “our worthy fellow citizens,” and begins to imagine the possibility of another Brazil, one that would welcome people of such evident spirit and understanding. Together they might discover a new path forward.

“History is not deceived by the rhetoric of the defeated,” da Cunha warns his readers, the urban white elite who falsely saw themselves as victorious. In the end, his hopeful observation proved true. Da Cunha’s vision, tentative and inconsistent, of a different Brazilian future eventually helped to make possible another way to redeem the nation’s past, despite high-minded aristocratic opposition. By the 1960s new political movements were emerging, populist in spirit and boasting vibrant artistic and intellectual expression, which even the dictatorship had trouble suppressing—though try it did. Violently.

One instantiation of this new way of conceiving the past occurred in 1981, as the dictatorship was losing ground. In a grand public event in the historic city of Recife, Brazilian priests conducted a Mass, the “Missa dos Quilombos,” that would, they believed, help “create a new history,” in the words of one participant.

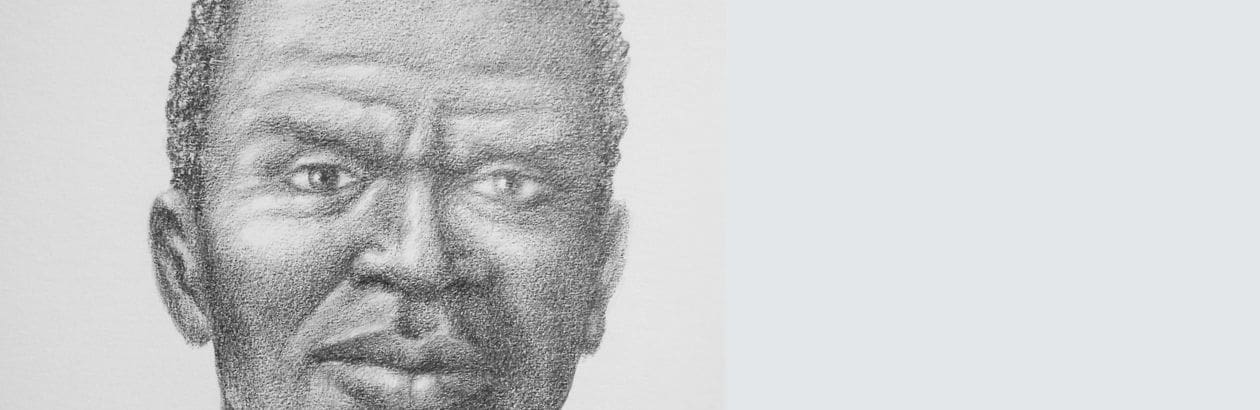

The occasion was the anniversary of the death of Zumbi dos Palmares, an escaped slave whom the crown had killed in 1695 while he was leading a community of fugitive slaves—communities known in Brazil as quilombos (among which scholars count Canudos). The power of this Mass in the nation’s consciousness—some eight thousand attended, and it was covered widely in the media—was enhanced by the participation of Milton Nascimento, the singular Brazilian singer-songwriter intimately identified with the people of Brazil. Afro-Brazilian himself, Nascimento composed the music for the Mass, weaving into it sounds and rhythms and words from the depths of the nation’s history, African, Indian, European.

In a song that he sang as a solo as the Mass began, he proclaimed a new basis for union, and a better reason for hope.

In the name of the Father, who made all flesh

the black and the white

both with red blood

In the name of the Son, Jesus our brother

who was born dark

of Abraham’s race

In the name of the Holy Spirit

the banner that waves

for the reveling Negro’s song

Today across Brazil actors and singers continue to stage this Mass, accompanied by dramatic interpretation, celebrating and commending its vision of a new people, gathered in the name of the God who, in Nascimento’s lyric, makes us “free by the Law of Love.” The Mass places Brazil’s history of depredation and triumph within the story of the cross. Even our own soul-stinging violence and heartwrenching pain, it proclaims, can be redeemed by this love, flowing from beyond history into time.

Brazil’s ordeal is far from over. But the nation’s origins don’t look like they did in 1950, let alone 1900. Its story is being retold. Zumbi dos Palmares is today a national hero. The people, back in control, have twice elected a factory-worker president. The nation’s new constitution protects the historic quilombos. Thanks to devotion to a common set of ideals, a true hope, however endangered, proceeds from the nation’s past, pushing its people forward.

Remembering well

King was right: We do have a sacred heritage. Every people does. But it’s not because our pasts are blameless—that could not be clearer. Nor is it because every nation is “great.” Rather, it’s because in the past each of our ancestors, every single day, received a holy gift: life itself, given moment by moment by God. Our pasts are sacred, in short, because life is. What did those who came before us do with this gift? Did they treasure it? Regard it with reverence? Make good on its hope?

These are questions the answers to which we, who today receive this same startling gift, need to know. We need to know these answers about our past for our own spiritual orientation, for our own hope of prosperity, for our own pursuit of the good.

As we look back, we don’t look back alone—something of which we’re particularly aware on historic national anniversaries, which make possible a collective reckoning that is difficult to achieve. On such occasions, we look back, we realize, as a we, as communities constituted for the public good. And if we have factions—liberal, evangelical, Catholic, secular, conservative, green, and more—then perhaps we also have hope: the hope that the goods each coalition preserves might lead to clarifying debates about how those goods have fared in time—and about whether they are, in fact, goods at all.

Our factions help us remember, too, that while life is sacred, systems of government are not, whether democracy or any other. Democracies, like all structures, finally stand or fall on the quality of life breathed into them, sector by sector, soul by soul. This is the citizenry’s calling: to breathe forth institutional life.

Christians, as they consider this calling, might take another cue from the singersongwriter Milton Nascimento. In a recent song, he recollects how he, having discovered his vocation, “wed himself to his people.” In doing so, he says, “the streets of the country” became “his altar.” Today, “the city is happy with the voice of its singer / the city wants to sing along.”

Sometimes the songs die out and the marriage fails. But it doesn’t have to. As King knew, a shared sense of a sacred past can help forge a union. True, the sense of a sacred past may also land you in jail. But that just might lead to freedom too.