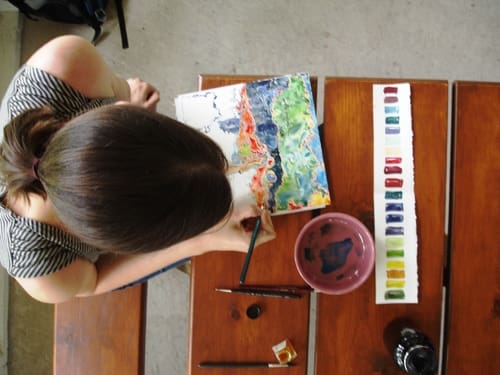

Stephanie Gehring is a writer, painter, teacher, and scholar-in-training. She holds an MFA in Creative Writing from Cornell, and her poetry has been published in The Fiddlehead, Poems and Plays, Folio, Meridian, and Ruminate.

Stephanie Gehring is a writer, painter, teacher, and scholar-in-training. She holds an MFA in Creative Writing from Cornell, and her poetry has been published in The Fiddlehead, Poems and Plays, Folio, Meridian, and Ruminate.

In your work, what are you creating, and what are you cultivating? (In Andy Crouch’s vernacular, what new culture are you making, and what good culture are you conserving and nurturing?)

Stephanie Gehring: When I was thirteen I had a drawing teacher who told me over and over that drawing is seeing. Today I am a writer, and those words feel as true about writing as they are about drawing. What I hope to cultivate is an increased capacity for attending, for seeing. I do this by making things with my words which I hope are worth my readers’ attention—things that have layers of richness that repay careful reading, or even re-reading. Things you can sit with. I also do it by paying loving attention in my work to my own story, to the lives and stories of others, to the particular material world (of fried-egg sandwiches, of willow-oak trees, of potholed streets with buses on them).

The new culture I am making is an attempt to say hold still and look at this. This is intricately linked to conserving and nurturing what is good and worth looking at; it is also intricately connected to an awareness of evil and suffering. What I believe about Christ makes it possible for me to believe that the world’s goodness is everywhere capable of speaking to me about God; and it also makes it possible to believe that the places of deepest damage (in me, in others, in creation) are places where God is tenderly present.

Who is the “public” for your work—who is it for, and how does it affect the lives of those who engage with it?

I’ve found my public chooses me more than I choose it. It’s mostly adults, though; and I might say it’s the kind of adult who finds the magazines The Sun, or Image, interesting. So far it has included church people and non-church people, academics and non-academics, people in the literary poetry world and people outside it. My best readers have been also my friends, and sometimes I have made new friends through writing; if it is not too abstract, I might say my ideal reader is someone who would like to make a friend through reading, in the way that one can be friends with a person by reading words on a page.

Why do you do what you do?

Because it is what I am made to do, and because I love doing it. It has been a slow process discovering this, and not a bolt from the blue or a thing I have known all my life. The process of discovery is ongoing, and has happened through reading books, through taking time to try things (should I be a painter? should I be a writer? should I be a teacher? should I be a scholar?). Most of all, however, it has come from being seen by people who have taken time with me and made space for me (by listening, or by giving me scholarships or food or space to live): from my parents to teachers to friends to mentors who have adopted me long-distance. These people have said, “You would not be good at that. Why are you trying to do it?” And they have said, “You are good at this. Keep doing it.” Or they have said, “Try this; I think it would be good for you.” Or, “I don’t know whether you should do this. Do you like it?”

|

What skills, proficiencies, and virtues does this work develop in you?

Patience, honesty, the ability to hold still, the ability to see what is really there (in myself or around me) rather than responding always to what I thought was there. The ability to notice God at work in unexpected ways, the ability to let other people be themselves and not try to force them into the shapes that will best meet my needs. What I do teaches me that saying “there is not enough time” is heresy; if God made the days twenty-four hours long and made me needing to spend nine of them sleeping, then it is not God who is telling me to fill each one with twenty hours of work. Also, my work teaches me a willingness to make something and throw it away and make it over, to let go even of my favourite part of a thing if it is not serving the whole.

These capacities are “developed in me” by my work sometimes in that it makes me repeatedly aware how deeply I lack most of them most of the time.

What five books would you recommend to someone interested in understanding or pursuing the sort of work you do?

Four Quartets by T. S. Eliot (for re-reading slowly and without any particular goal in mind, and for trusting that you are capable of understanding what you need to understand in it, and that next time it will be more. Also, if you don’t love philosophy, begin with the second section).

The Writing Life by Annie Dillard (for ruthless advice, beautifully put).

The Road by Cormack McCarthy (for tenderness set in the midst of atrocity).

The Man Who Was Thursday by G.K. Chesterton (for an irrepressibly, outrageously glad writer meditating on Job).

Gravity and Grace by Simone Weil (for a ferocious and compassionate intellect giving aphoristic reports on glimpses of the world and of God; useful even—or maybe especially—when her conclusion is not one with which you can agree).

What do you do for fun?

I sometimes do improv comedy (badly and gladly) with a group of friends and no audience. I watch Youtube videos with my housemates. I cook, and eat food with people. I listen to music, if possible with people who love it and can tell me why. I go for very long walks, with people or alone. I listen to birds. I buy roses. I watch movies (a recent favourite is The Secret of Kells, which leads to another thing I do for fun: I am learning to draw Celtic knots). I draw and paint and do calligraphy. And recently I started playing the piano, which I hadn’t done in fifteen years. I’m very painstakingly (just for myself and no one else) learning Beethoven’s Moonlight Sonata (which, as a teenager in Germany, I called the “Moonshine Sonata” to my visiting American uncle).