A

No longer do I call you servants. . . . I have called you friends.

—John 15:15

Aristotle uses the term “civic friendship” to describe the bonds that emerge from a sense of common purpose in a shared political project. “Citizens are civic friends,” the Aristotelian philosopher Paul Ludwig writes, “when they share an agreement about important practical matters: preeminently, they agree about the regime, their political system.” Communal commitment to a common endeavour results in a kind of general goodwill of citizens toward one another—the seeds of civic friendship. It is what allows a society to remain whole and undivided rather than fragmenting into warring subcommunities. It is also a good description of what American life so conspicuously lacks.

How, though, does a society ensure that its members do believe themselves to be in it together, with common goals and shared outcomes? In December 1961, Martin Luther King Jr. delivered remarks to the Fourth AFL-CIO Constitutional Convention in Miami Beach, and attempted to answer that question.

King was stepping into a heated and challenging situation. The AFL-CIO was plagued by internal acrimony and public hesitation regarding civil rights. King chose to address the tension directly. He told the assembled delegates that the civil rights and labor movements had to work together, because their aims were inseparable. Democracy was not complete and could not remain stable without a working public empowered to fully participate in the nation’s economic life. A voice at the ballot box represented only incomplete equality without a collective voice in the workplace. Deploying the dream motif that would later define his most celebrated language, King invited his audience to understand what was at stake. “Together,” he said, speaking of the civil rights and labour movements, “we can be the architects of democracy,” and “bring into full realization the dream of American democracy—a dream yet unfulfilled.”

In the present moment of frayed social fabric and declining faith in the American democratic project, we should listen anew to the wisdom of Aristotle and King. Civic friendship requires the widespread belief that the American experiment is a shared enterprise. Making such a grand belief possible, we learn, requires starting in a prosaic and perhaps unexpected place: the workplace. It requires recovering an understanding of the workplace as a site of cooperative endeavour rather than conflict, exploitation, and alienation. Such an understanding of work requires a renewed economics that reflects the reality of what labour is and what it does, and policy that instantiates that reality in mechanisms for worker voice and power. In a pluralistic democracy, as King understood, worker power is essential for any hope of healthy civic friendship.

Recovering the Workplace for Civic Friendship

The wider decline in faith in American democracy is accompanied by declining faith in American institutions—including the workplace. A majority of American workers experience what MIT professor Thomas Kochan calls the voice gap: the yawning distance between the voice they want at work, and the voice they understand themselves to have. Between one-half and three-fifths of American workers have less influence than they think they should on many workplace matters—compensation and benefits, but also job security, protection from abuses, promotions, how new technologies are implemented, their employer’s values, and the respect shown to employees.

The effect of this gap on workers is profound. American Compass’s A Better Bargain Survey, using a common metric called Net Promoter Score, asked workers how likely they would be to recommend their job to a friend. The number of “promoters” less the share of detractors offers a simple measure of worker sentiment toward their employers. Workers who experience a voice gap give their jobs a Net Promotor Score of -48 percent. Poor labour-management relations negatively affect job satisfactions even more strongly than objective measures of job quality like predictable hours: workers who report poor labour-management relations give their jobs a Net Promotor Score -94 percent, compared to +55 for those workers with excellent relations with management. American workers want to feel that they, their managers, and the owners of their employing business are “in it together,” and party to a meaningfully shared endeavour. All too often, they do not. As Yuval Levin puts it in the Fractured Republic, “The place and promise of work in the lives of many Americans . . . has faded.”

The workplace is an institution uniquely suited to foster civic friendship among its participants.

This represents an immense lost opportunity. The workplace is an institution uniquely suited to foster civic friendship among its participants. For Aristotle, civic friendship does not require deep affection or elevated altruism—an impossible expectation to have of all members of a society, or even all co-workers in a given workplace. Aristotle distinguishes types of friendship according to what animates them. Friendships of pleasure are based on the enjoyment friends derive from one another; friendships of virtue, on admiration for the quality of one another’s character. Civic friendship, by contrast, is a friendship of utility. Its foundation is not deep altruism toward one’s fellows but the like-mindedness that results from the experience of mutual interdependence—from recognizing the reality of a shared lot and common fate. For Aristotle, civic friendship doesn’t require me to like you all that much. It requires me to acknowledge that, as a matter of objective reality, I need you. In recognizing the stark, inescapable fact of our mutual interdependence, the value of mutual cooperation becomes clearer. This interdependence, and the value of the cooperation it points us toward, is especially applicable to our economic relationships.

This gives the workplace enormous power to nurture civic friendship and model it to society at large. St. John Paul II understood the potential of the workplace to contribute to civic “togetherness” in this way. In 1981 he wrote, “It is characteristic of work that it first and foremost unites people. In this consists its social power: the power to build a community. In the final analysis, both those who work and those who manage the means of production or who own them must in some way be united in this community.

The precondition of work’s community-building capacity, John Paul II teaches, is the understanding that capital, management, and labour are parties to the same endeavour—parties that need one another—whether they wish to be or not. Such an understanding requires an economic theory rooted in reality as it actually is, rather as economists might wish it to be.

The Great Divorce (of Labour and Capital)

An Econ 101 textbook, informed by the orthodoxies of free-market fundamentalism, will likely tell you that labour is an input of production. Like other inputs, labour can be purchased and sold, reorganized, downsized, or discarded as the service of maximal shareholder value may require. But labour is clearly not like other inputs. Workers assume personal risk alongside investors—often greater risk. Workers bring invaluable insights to the process of innovation and production. They have perspectives that can improve corporate strategy to the benefit of all concerned. Workers are better understood not as inputs but as co-creators of economic value alongside management and investors.

In short, “labour” is simply another term for “people.” As Oren Cass argues in The Once and Future Worker, “People are not products” and are not “created for the purpose of selling their labor.” Far from being a faithful account of how the world really works, market fundamentalism requires extreme intellectual gymnastics, fit to make an Olympian wince in pain. It takes serious commitment to sustain the fiction that workers are somehow other than what they obviously are: human beings who not only possess inherent dignity and moral worth but are also essential partners in the process of value creation, on which management and investors fundamentally depend.

The contortions demanded by the economic priesthood are not merely mental. American economic policy has engaged in a sustained, decades-long effort to bend the real world to fit its pretenses that capital and labour need not be interdependent within the context of political communities. Healthy capitalism recognizes that all parties to the economic engine have appropriate relationships to another, defined within the contours of the societies they occupy. Healthy economic policy thus establishes structures to protect and promote those relationships. Recent decades of economic orthodoxy has done the opposite, and attempted to divorce labour and capital from one another in contravention of what healthy capitalism requires.

This is most obviously true in the case of globalization and unfettered free trade, which is premised on the disposability of labour by the capital that occupies the same national community. If local labour costs too much, cheaper factor inputs can be found elsewhere, and whole productive enterprises offshored. No matter that this is generally not so much wage arbitrage as oppression arbitrage, and that international labour is usually cheaper due to that country’s own indulgence in a view of labour as exploitable. The promised economic gifts of globalization have not materialized for working people. Nor has globalization’s offer of cheap consumer goods and globally monochrome consumer “culture” in exchange for widespread economic degradation and social fragmentation proved politically sustainable. Both Democratic and Republican politicians have been obliged to distance themselves—at least rhetorically—from their party’s prior enthusiasm for globalization in light of the American voting public’s widespread anger at its consequences.

American workers have been sent the clear message that they are not at all full participants in a shared enterprise, but every bit the disposable inputs market fundamentalists tell them they are.

Financialization has also assaulted the inconvenient truth of labour and capital’s interdependence, beginning by redefining the meaning of economic value. Value need not refer to productive activity. It can instead mean whatever speculative financial activity the market puts a price on, and be elevated out of the messy, physical world in which most workers are to be found. Such gymnastics allow financialized capital not only to ignore the importance of production to a society but also to lionize its own extraction of value at workers’ and local communities’ expense by redefining it as a positive economic contribution.

These economic contortions deliberately ignore the boundaries that hold labour and capital together in their proper, healthy relationship. As attempts to ignore or evade basic truths usually are, the effort has been destructive. The scriptural passage so often invoked in wedding ceremonies warns that what God has joined together no one should put asunder. A similar warning applies regarding what economic reality has joined together. The attempt to forcibly divorce labour from capital and liberate capital to seek its own best fortunes elsewhere has broken the parameters that define healthy capitalism, and left capitalism’s children much the worse off. American workers have been sent the clear message that they are not at all full participants in a shared enterprise, but every bit the disposable inputs market fundamentalists tell them they are.

A better—that is, a more truthful—economics would push policy in a very different direction. It would recommend trade policy that rejects the idea that society benefits from cheaper and more plentiful goods, if the price of those goods is abandoning workers and shipping their livelihoods across the sea—especially to abusive, oppressive, and dangerous regimes. It would recommend tax policy that unapologetically promotes actually productive activity that can economically anchor local communities, and financial regulation that holds firms responsible when workers and communities pay the price for their speculative choices. Rather than relying on tropes about “work Americans won’t do” and “worker shortages” to paint working people as lazy, a better economics would seek to understand what workers do require to consider a job worth doing, and whether employers are creating their own labour shortage by ignoring capable job applicants. And it would demand that policy give workers a collective voice in the workplace.

Worker Power and the Meaning of Participation

The result of labour and capital’s divorce has been the degradation of worker voice and power. Due to the ease with which workers can be replaced, a legal environment hostile both to union organizing and to experimenting with new kinds of organizing, and the contemporary labour movement’s own tone-deafness regarding what workers truly want, very few American workers have collective representation at work. Six percent of American private-sector workers are union members. This lack of voice is not only tolerated but largely expected. Why else would it have been such shocking news when the Amazon Labor Union won its unionization drive in Staten Island in April 2022? That is not how that story usually goes.

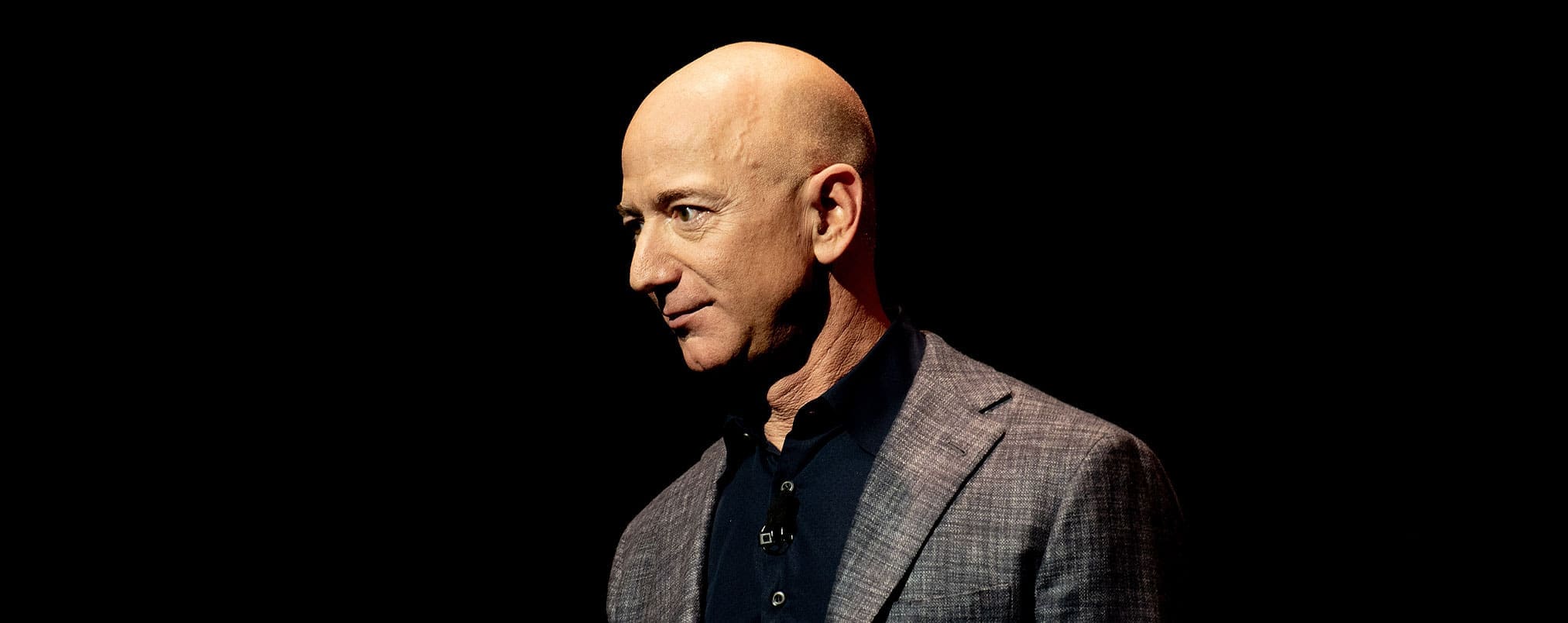

Aristotle and King tell us that degraded worker power is not compatible with civic friendship. A future in which workers understand themselves as powerless at work—as subjects to what Elizabeth Anderson provocatively calls the “private government” of unaccountable employers—suggests a view of workers as less than full partners in economic life. This vision of workers seems to be precisely what some corporate leaders have in mind. The comedian Jon Stewart recounts being at dinner with Barrack Obama and Amazon founder Jeff Bezos, and hearing Bezos describe a future in which “workers’ primary task was to deliver goods and services” to the ultra-wealthy. Stewart suggested this was a recipe for revolution; Obama sensibly agreed. The social shape of work matters. An economy premised on servility, especially atomized servility in which workers cannot speak collectively, is inherently democratically unstable.

Civic friendship rests on an understanding of mutual interdependence and the utility of cooperation.

Civic friendship, by contrast, rests on an understanding of mutual interdependence and the utility of cooperation. This requires policy that facilitates mutual economic cooperation rather than the subservience of some to others. As the political scientist Dominique Déry argues, Aristotelian civic friendship depends on “rules that structure fellow citizens’ interactions so that . . . some citizens are not always sacrificing things for others.” These structures reflect and protect the understanding that all parties concerned are full participants in their common endeavour.

Those structures must therefore include mechanisms for worker voice and power. Even Adam Smith and John Stuart Mill, so frequently cited by libertarian and neoliberal economists, understood that individual workers would always inevitably be overpowered by employers if left alone and isolated. “Upon all ordinary occasions,” Smith points out in the Wealth of Nations, employers “have the advantage in the dispute, and force [workers] into a compliance with their terms.” Mill understands that “the labourer in an isolated condition, unable to hold out even against a single employer . . . will, as a rule, find his wages kept down at the lower limit,” while workers “sufficiently organized in Unions may, under favourable circumstances, attain to the higher.” Mill is not ambiguous as to which outcome is morally and socially preferable, adding that “whoever does not wish that the labourers may prevail . . . must have a standard of morals, and a conception of the most desirable state of society, widely different from those of . . . the present writer.”

Thus does John Paul II conclude that the workplace’s capacity to build healthy community cannot be realized without collective worker organizations:

In the light of this fundamental structure of all work—in the light of the fact that, in the final analysis, labour and capital are indispensable components of the process of production in any social system—it is clear that, even if it is because of their work needs that people unite to secure their rights, their union remains a constructive factor of social order and solidarity, and it is impossible to ignore it.

Perhaps the late pope also understood what Aristotle knew: that civic friendship can grow into deeper and less utilitarian forms of friendship. Worker organizations provide the structures that allow workers and employers to meet as equals and partners, making workplace civic friendship possible. But they can also connect their members at the interpersonal level—not only as members of a common workforce with shared concerns but also as members of a common community. Precisely in giving workers the practical ability to represent their interests—that is, the ability to fully participate as partners in economic life—collective voice and power contribute to a stable and healthy social fabric, and offer workers a chance to experience the dignity, meaning, and social cohesion that can come from solidarity.

From Servants to Friends

In the fifteenth chapter of St. John’s Gospel, Christ paradoxically declares that he no longer calls his disciples servants, but friends—if they “do whatever I command you.” This statement in isolation seems flatly self-contradictory. How can friendship be conditioned on subservience? But the paradox resolves quickly in the light of his command’s content, issued in the same breath. “This is my command, that you love one another.”

Achieving the lofty goal of civic friendship must begin with accepting the practical, even mundane fact of our economic interdependence.

For the Gospel writer, the only One with legitimate authority to demand subservience instead wields that authority to joyfully dismantle the idea that we can ever legitimately demand subservience from one another. Thus the path to becoming no longer merely servants of God, but God’s friends, lies in obedience to that great commandment that we first regard one another as friends—as human persons equal in dignity and value, none of whom may dominate another without doing violence to the image of God each one bears. I am not—and cannot be, we are taught—reconciled to ultimate reality without first recognizing the more immediate, earthly reality of my interdependence and equal standing with other people.

So too in economic and civic life. Achieving the lofty goal of civic friendship must begin with accepting the practical, even mundane fact of our economic interdependence. This acceptance is what characterizes healthy capitalism. Policy that attempts to ignore, deny, or end-run this fact and treat workers as disposable inputs only fractures society further, and increases the likelihood of democratic breakdown. The workplace can be a site for nurturing civic friendship—an ideal site, if we let it be. But this will not be possible without allowing work to be a truly mutual and shared endeavour, in which all parties participate fully and share power between them.

The necessity of economic participation to civic stability is something King clearly understood and loudly proclaimed. The philosopher Tommie Shelby summarizes King’s view bluntly:

This understanding is why King “not only fought against discrimination as an evil but for civic participation as a good,” and why he linked participation in democracy with participation in economic life. Only from such soil, King implies, can something like Aristotle’s civic friendship emerge.

On October 7, 1965, King tried yet again to appeal to the labour movement with this truth, this time at the Illinois State AFL-CIO convention. He again tied democratic stability to economic security. The bright future of a unified American republic, he said, was to be found in both civil and economic participation, for the first cannot endure without the second—and the second requires workers to have a real voice in their own economic fate. Then, and only then, King promised, “the brotherhood of man, undergirded by economic security, will be a thrilling and creative reality.”