In Judith Wallerstein’s bestseller The Unexpected Legacy of Divorce, one now-adult child of divorce remembers, “There were times when Mom would come home late from work and I’d need help with something for school. . . . She’d tell me I’d have to do the best I could on my own because she needed to study. Then she’d lock herself in the bathroom. I remember sitting on the floor outside the bathroom door, listening to her turn the pages in her textbook.” For this little girl, the closed bathroom door didn’t just mean she was alone physically; it meant she was emotionally isolated.

Families today are subject—like everything else—to the individualism of the age. Where marriage was once an institution that tied you not just to another person, but to a broader community all the way up to the public at large, today one’s participation in family life is, more or less, a lifestyle choice. Love and relationships are part of a process of self-actualization. Having children, for example, might be like any other interesting experience, like foreign travel or learning a new language. In this context, family is just as likely to present an obstacle to finding one’s true self as an encouragement to it. One might even go so far as to say the pursuit of autonomy is inherently socially isolating, and insofar as autonomy has worked its way into marriage and family, we are creating a self-perpetuating cycle of loneliness.

The Data Tell a Story

In Canada, Census 2016 marked the first time “living alone” was a larger category than all other family types. The “one-person household” made up 28.2 percent of all households in that year. The same is true in the United States. Eric Klinenberg, the author of Going Solo, tells us of the American reality that “people who live alone are tied with childless couples as the most prominent residential type—more common than the nuclear family, the multigenerational family, and the roommate or group home.”

Marriage rates are going down, and cohabitation, an inherently less stable form of partnership, is on the rise in the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom. We are officially counting other family forms now as well, evidence of their growing sample size. In Census 2016, Statistics Canada reports that “lone-parent families and stepfamilies . . . are not new phenomena. However, these families are more frequent and more diverse than before.”

At the same time, there has been an explosion in the study of social isolation. Interest in this topic likely reflects an increase in social isolation due to aging populations with fewer children to care for the elderly. Statistics Canada tells us the last time Canada reached the replacement fertility rate of 2.1 was 1971. For the United States and the United Kingdom this is 2001 and 1973 respectively. Across the globe, fertility is in freefall. In a 2016 survey, Canadians reported that they expect the number of elderly they are caring for to double (from 0.5 to 1.2) in the next ten years.

Ascendant Individualism

Freedom, independence, and autonomy are good things. But they need to be balanced with other attributes such as duty, self-sacrifice, and community. As economist Jennifer Roback Morse notes in her book Love and Economics, “libertarianism” has little place in family life, where bonds are held together by love and covenant. The family project, starting with marriage, involves the creation of a small community for children that would collapse if run purely by contract. The small society of the family shows children what it means to be socialized and contributing adults via the teaching and example of their parents and family. (Socialization, incidentally, does not mean the same thing as being “social.” Rather, socialization in childrearing means rendering children fit for society so that children can grow and mature into contributing adults who can respectfully interact with others in community, whether at work or home, with colleagues, family, or friends.) Marriage marks the start of lifelong love, and in spite of our high divorce rates, married relationships are more likely to last a lifetime as contrasted with other relationship forms, like living together. It is in the microcosm of stable family that we learn how to stick together through good times and bad, as wedding vows continue to profess.

Yet sticking together, much as we talk about it, is increasingly difficult. Individualism is deeply embedded in North American founding philosophies, so it’s perhaps unsurprising that families function today as a collection of individuals. Almost two hundred years ago the French philosopher Alexis de Tocqueville worried about ascendant individualism in his largely positive impressions of America. Jonathan Grant, author of Divine Sex, examines Tocqueville’s concerns: He worried that “American ‘individualism’ was a force that would eventually isolate people from each other.”

Building on Tocqueville’s concerns, modern psychology can now study and survey our views of identity, individualism, and family. Grant shows in his book how prescient Tocqueville’s concerns were. One psychologist by the name of Paul Vitz calls our modern outlook “selfism.” Selfism, Grant explains, “views each person as an autonomous being and often locates the source of our problems in formative relationships with our parents and sibling.” He concludes, “Within this model, true freedom involves becoming self-sufficient and freeing ourselves from the control and dysfunction of other people.”

As may be obvious, selfism cannot possibly do anything good for marriage, an “other-centred” institution. All too often today, we find adults freeing themselves from their marriages, in hot pursuit of elusive happiness goals, unaware that they bring themselves—and their problems—into the next marriage. Indeed, second and third marriages are more likely to fail than first marriages. Research also tells us that those who bear through a rough time in an unhappy marriage and stick together are more likely to be happy five years down the road than those who divorce.

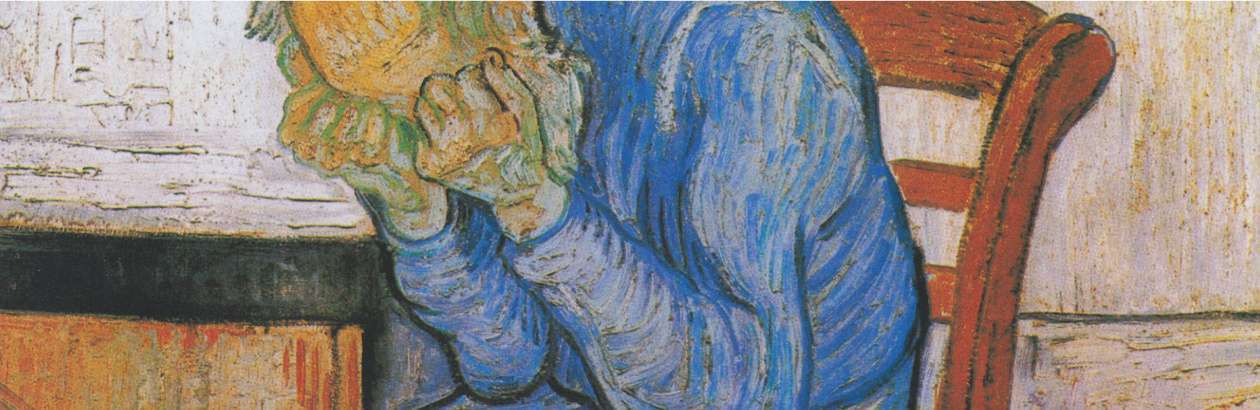

Every year a couple stays married, every disagreement they navigate and certainly every child who is born creates a legacy of strengths for that couple that is at best diluted and, at worst, destroyed if the marriage fails. Barbara Dafoe Whitehead, author of The Divorce Culture, puts it this way:

An elderly couple, married for fifty years, is likely to enjoy a substantial body of social and emotional capital, generated through their long-lasting marriage, which they can draw upon in caring for each other and for themselves as they age. Similarly, children who grow up in stable, two-parent married households are the beneficiaries of the social and emotional capital accumulated over time as a result of an enduring marriage bond. . . . As family bonds become increasingly fragile and vulnerable to disruption, they become less permanent and thus less capable of generating such forms of help, financial resources, and mutual support.

The Many Paths to Isolation

It is this lack of stable, and permanent, bonds that is the mark of social isolation in modern families. This lack of stability occurs in several different ways. I will name but three. First, some find it difficult to form a family in the first place. The “success sequence” involves finishing school, then getting married, then having children. The order is important, and it was once understood without speaking about it. This shared path from adolescence into adulthood and families of our own no longer exists. One successful and dynamic friend is envied for her hectic but rewarding work life alongside other hobby and volunteer commitments. Yet she says simply this: “I hate going home and being alone.”

Others will find isolation within their own family, and this makes up our second example. Mothers, for example, can feel isolated after having a baby. Most women are taught over years of schooling that meaning in life is found outside family in the paid workforce. In this context, a small baby is a distraction from what really matters. One new mother says she is depressed, alone and anxious at home, and eagerly awaiting the relief of a return to work. Who can blame her? If social networks are difficult to find outside the GDP-enhancing work world, then being home with a child means a lack of community at the time when it is most essential. (A lack of community outside work is a health concern for men as well.)

Finally, if one baby is isolating, there is little incentive to have another. Whether for this reason or a myriad others, the stats tell us we are simply not reproducing. For decades, families in North America have been shrinking. Bigger certainly isn’t always better, but where social isolation is the problem, smaller families in purely practical terms means fewer people to connect with, fewer people to come to gatherings, and fewer people to take care of Dad when Mom passes away and Dad needs care. This also means fewer people to pay into social welfare nets, resulting in an existential crisis of who will cover costs when the tax base is disappearing. There are clear reasons why Toys “R” Us went under—and most of us believe it’s because we are all shopping online. That’s part of it, but it’s worth noting any toy-related business is relying on a dwindling customer base, something Toys “R” Us alluded to in their closing press release: “Most of our end-customers are newborns and children and, as a result, our revenue are dependent on the birthrates in countries where we operate. In recent years, many countries’ birthrates have dropped or stagnated as their population ages.” Other outcomes include changes in city planning, with less space for parks and more for one-bedroom condos. Children today are mostly cost, not benefit, and the expensive and generous family policies in many nations, including an assortment of benefits, have failed to tease the total fertility rate up to replacement levels.

The Sexual Revolution: Delivering on Isolation and Loneliness

Many of these family changes are wrapped in the mantel of the sexual revolution. While it is hard to pinpoint the start time for the sexual revolution, many agree the advent of the birth control pill, approved by the FDA for widespread use in 1960, is a good marker. Look for a person for whom sex means marriage and most likely babies for whom you are responsible, and for whom divorce is not normal. That person will almost certainly have come of age before the 1960s, which makes this an obviously aging demographic. Fewer and fewer are aware of living in more stable family times, when having sex meant getting and staying married, even though that came with baggage of its own.

When Glynn Harrison wrote his book A Better Story: God, Sex and Human Flourishing in 2017, he intended it to ensure that Christians know why Christian sexual ethics tell a better story about human beings and our flourishing. To his credit, he begins with substantive detail on how and why Christian churches have failed on the issue of sexuality by creating and promoting a culture of shame and hypocrisy about sex. “Christendom’s dysfunctional attitudes to sex helped create the discontent that triggered the [sexual] revolution and propelled it forwards,” he writes. Christians, the very people who claimed to have higher standards, were ill-equipped to respond to rising autonomy and authenticity. Yet Harrison does another clever thing, which is to ask questions about whether the sexual revolution has succeeded by its own standards. Are we all living happily ever after? Are we having lots of free love? Has the lack of structure in family life propelled us to new heights?

The answer there might be funny if it weren’t so sad. Harrison quotes an Oxford statistician who has studied sex lives and attitudes toward sex:

At [this] rate of decline . . . a simple, but extremely naïve, extrapolation would predict that by 2040 the average person will not be having any sex at all. I rather suspect this will not be the case, but this still leaves the crucial question: why is there less sex going on?

In short, the sexual revolution, which intended to bring more freedom to have more sex without shame or guilt, is failing to deliver in precisely that category. It all sounds terribly lonely.

So many aspects of the sexual revolution were pitched specifically to women under the auspices of freedom. While there can be no doubt that some women were repressed or restrained in traditional family life, the solution has swung the proverbial pendulum too far. Not all reforms done with feminist intent actually achieved freedom for women. The historic passing of no-fault divorce is a classic example of an anti-family and anti-woman act purportedly done for women. A 2017 book about they myth of the good divorce called Torn Asunder highlights that the men who introduced no-fault divorce in California in 1969 were “not particularly concerned about the welfare of women.” They instead wanted to “reduce fraud, ameliorate husbands’ alimony burdens, and streamline the divorce process into a less controversial, more perfunctory proceeding.” What many fail to realize is that the advent of unilateral (no-fault) divorce created an environment where a man no longer needed to stand by his wife and children. Marriage, as it turns out, constrains men too.

The constraints of marriage, applied equally to men and women, had some benefits for both. Today’s era of free sex does not serve men well either. Not every guy gets the girl, let alone any girl—as evidenced by the waning amount of sex we are having. Here, many men and some women turn to pornography and get trapped in that lonely screen-interface addiction.

The failure of the sexual revolution for women is such that scholars now discuss the paradox of increasing unhappiness for women in particular. The paradox refers to the objective reality that women’s freedoms are greater now, and yet female happiness declines. One journalist writing recently in Oprah details the very lives of women falling apart. She calls a friend to ask about people to interview: “Do you know anyone having a midlife crisis I could talk to?” Her friend replies: “I’m trying to think of any woman I know who’s not.”

The Search for Something Different

Rising social isolation cannot be blamed exclusively on family trends. Certainly, this essay gives scant consideration to economics, which without any doubt play into our isolated malaise.

Still, it takes something of a wilful blindness not to see connections between our ideological commitments to individualism, sexual freedom, and small families and the effects of those commitments on loneliness and isolation, including waning social connections and the rise in living and feeling alone.

In Adam and Ever After the Pill, author and social commentator Mary Eberstadt likens the will to disbelieve that the sexual revolution has wrought pain in people’s lives to the academy’s inability to see anything negative about communism or Soviet Russia during the Cold War. Yet it may just be that beauty will rise from the ashes. Many of those most willing to believe there are isolating effects to recent family trends do so out of the pain of experience.

If there is one thing you cannot say about Samantha (not her real name), a mother of four children under five, it’s that she is lonely. Wishing she had more time for sleep or desiring a quiet moment, yes, but lonely, no. It is in the disarray of her life, in which she and her husband tag-team care of their children, that one sees a hopeful thread. The hopefulness lies not only in the fact that she has, by today’s standards, a large and thriving family and a marriage that is very much together after ten years, but that she also needs and receives help. A single person is needed here—to step in and watch the kids for a couple of hours. To bring a meal. To provide adult conversation.

This kind of family may be the minority, but they are out there. Neither does it take four kids under five. One will do the trick. If people are isolated, they need look no further than their own street for finding community. Some organizations aim to facilitate that community and act as a bridge. Take for example Safe Families. This chapter-based organization, which is expanding from the United States into Canada, acts as family for people who are isolated. Perhaps a single mother gets sick and needs to go into treatment. Via Safe Families, she can find an approved safe home in the community who takes care of her children while she gets better. The single mother doesn’t need to worry, and once she is better, she encounters friends beyond the family who took her kids who are there for lasting relationship. This type of agency also lessens the load of the Children’s Aid Societies, which are over burdened as it is.

Other groups have sprung up to empower people to go and spend time with those at the end of life, dying in palliative-care homes. This might seem daunting at first, but the Dying Healed program helps people find the courage and teaches the right listening skills to be there for someone at the end of life.

For some, family breakdown engenders the search for something different. Though there are many obstacles in today’s world to living a different family existence, there are almost limitless opportunities to begin pouring into others and, by so doing, creating the loving relationship we ourselves lack. In time, there will be more willingness to discuss and listen to “a better story” about family, leading out of isolation and into community.