War disrupts social capital. It inevitably alters the social fabric within which individuals function. Of course, without a doubt, there are countless physical effects of war. These are easy to see and, sometimes, easy to rebuild. But rebuilding a society—its fabric, ability to function, or its social bonds—is a much heavier task.

Physically, the carnage of war is evident on infrastructure—on bricks and mortar. In London, England, the old buildings still hold the damage of war, their sides pock-marked with remembrance of bombs dropped during the Blitzkrieg. The holes were never filled in.

In Amsterdam, the hiding place for Anne Frank and her family remains preserved. The walls—covered with thick panes of plastic to preserve its history—tell the story of a family who so hoped to make it through the dark days of the Holocaust.

Infrastructure tells a story of war through damaged buildings and ravaged roads. So do the bodies of men and women marked by it—missing limbs tell the stark reality of loss. A man’s slow movement speaks of someone pained by the scars of shrapnel.

But beyond the stark physical damage of war, the carnage of war insidiously appears in society, corroding our capacity to create and sustain flourishing cultural institutions. Most unexpected are the lost social bonds a society needs to thrive. Robert Putnam argues that communities that thrive have ample social capital: they build connections, norms, and have preferential treatment for members of their society. On a practical level, they have social clubs and systems of exchange (a cup of sugar, a good book)—all of which allow individuals to thrive. An absence of social capital has negative effects. In Italy, Putnam found that regions with low social capital had higher corruption, less stable governments, and were less economically viable.

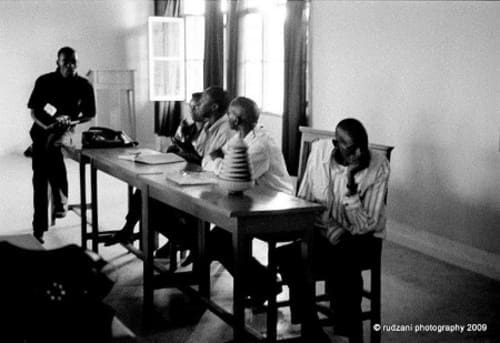

War leaves behind a society of fractured trust. At the end of Rwanda’s genocide—which resulted in the murder of 800,000 Tutsis—the state set up gacaca courts to speed up prosecution and to foster reconciliation among citizens. Prisoners confessed to their crimes. Victims shared stories of pain and massacre. After confession, many prisoners were sent home, often without additional sentences but perhaps with community service orders. Victim and perpetrator often found themselves living in the same community with only memories of the carnage of war between them. Returning neighbours were no longer neutral inhabitants in a community. They were enemies who had slaughtered victims’ families. Victims were reminders of the evil committed by the perpetrator. Perhaps they continued to fuel the hatred of the perpetrator. Regardless of the underlying emotions and sentiment, any systems of trust and community that existed before the war were shattered, and a new reality of a further fractured community of distrust exists.

|

Likewise in Cambodia. A society of trust is required for social capital to thrive, but many of the men and women who held positions of authority in the Pol Pot regime remain in positions of power in the government. It means Cambodians feel like they cannot trust their government.

Rwanda and Cambodia can be lessons to us for Syria or Libya. Hundreds of thousands Syrians have been displaced to refugee camps. At present, this breach in systems of community or norms has undoubtedly hindered the ability of individuals to maintain or build social capital during displacement. Upon return to their communities, social bonds will be undoubtedly changed. So, during a time of rebuilding, not only will local and national governments be required to deal with broken infrastructure, they’ll be required to create an environment that advances social capital for communities.

One practical step is to invest in institutions that foster the benefits associated with family and community. Churches, in particular, come to mind—these act as bastions of protection, shelter, community, brotherly love, compassion, and sharing. During war, these institutions have found themselves in the line of fire. In Syria in October, 2013, a bomb was placed in a confessional box at one of the world’s oldest churches. Car bombs have been planted outside churches. These institutions become targets because their destruction will weaken people, their connections to each other, and, ultimately their resolve—for survival, for victory. Rebuilding these institutions in the aftermath of war become symbols of hope and restoration for community.

It is well known that the end of war can leave an entire country with diminished capacity to function, create, and contribute to its own rebuilding. War plagues the mind, often appearing as post-traumatic stress disorder. When war has happened, an entire nation or people group can suffer from debilitating PTSD. Cambodia is likely one of those countries. With millions of Cambodians murdered, the victims, their children, and countless orphans grew up in a traumatized nation.

Theary Seng, in a research presentation in 2007, noted that fear is a common symptom in Cambodians—blocking creativity, engagement, and a “healthy life.” These individuals fail to be engaged in life around them—they may fail to raise healthy, well-rounded children, or may fail to be a good wife, husband, son, or daughter. Their disengagement can fragment the nuclear family—a critical component of a thriving society. On a national level, these individuals may fail to contribute their creativity and craft to society—components critical to rebuilding. When governments, social institutions, and NGOs collaborate on rebuilding a country, it should be a requirement to ensure that the populace is emotionally and psychologically healthy.

Here it is important to mention that war obviously disrupts the economy, virtually wiping out international and national trade. With infrastructure damaged—roads, stores, and factories, for example—it is nearly impossible for the country to provide the needs of its populace, much less engage in external trade. As a result, the country is plunged further into economic despair and its people are without opportunity or ability to make or earn a living. Suddenly, poverty becomes a reality and survival the only option.

Not only that, governments will be required to address the “lost” years spent in refugee camps—years when social capital is largely defunct and practical social services are less available. The United Nations estimates that a new baby is born to a Syrian refugee family every hour. Many of those children will not receive birth certificates. In the years to come, without a birth certificate, these children—perhaps by then young adults—will be vulnerable to a host of abuses, including human trafficking and other forms of exploitation. These children need birth certificates. Moreover, about 500,000 Syrian children are at risk of contracting polio because of missed vaccinations due to the civil war. These children need vaccinations. These practical items need to be addressed at the end of a war. While it may take years for these effects to be seen, they will appear in society eventually—human trafficking could increase exponentially, or an outbreak of polio could wipe out a generation. While NGOs will work hard to fill in the gap at refugee camps, citizens will return to their country and their governments will need to deal with the repercussions of these missed practicalities.

Because war happens at a distance, it is easy to forget the innocent citizenry it affects. Our ability to forget is evidenced in our response to pleas for help for Syria. When Haiti was stuck by the tragic earthquake, Oxfam raised $38 million to help Haitians. In comparison, it has only been able to raise $700,000 for the people of Syria. Evidence indicates that responses to natural disaster are higher than response to “man-made” disaster. Yet, in both scenarios, innocent individuals are affected by circumstances outside their control. Innocent victims of war did not invite war into their backyards. External forces made war a reality.

When the war ends, the citizenry will pick up the pieces and try to rebuild a shattered society. But because the lasting wounds of war affect just those aspects of humanity we need to “make culture,” we can see what others need to come alongside and join the work of rebuilding social architecture. As North Americans, most of whom do not bear these wounds, we have both the culture-making capacity and the resources to help our global neighbours. We can ask for investment by governments and other NGOs in programs that focus on rebuilding social capital, providing psychological counselling to citizens dealing with post-traumatic stress disorder, or providing lapsed social services to those who need it. These would all be critical first steps in the recreation of social capital, enabling a traumatized people to rebuild the capacity to once again make culture. Those of us invested in North American social architecture should love our global, war-torn neighbours by enabling them to do the same.