M

Most of us treat Christmas as one brief day. It consists of equal parts gift opening, playtime for kids (perhaps matched by naps for tired parents), a big meal, and maybe a football game. I call that—as many would—a splendid day. It’s even better if there’s snow outside and a fire blazing.

But it passes quickly. By day’s end, we’re fully ready to be online again, and we each do our part to conclude fittingly this holiday that commemorates a most improbable strategy for redemption—that is, we redeem our iTunes gift cards for albums with one or two bonus tracks.

Maybe a church service is involved; maybe not. Some may consider themselves lucky to attend on Christmas Eve instead—light a few candles, sing some carols, and keep the actual Christmas day free. More time for family, of course. Don’t get me wrong: I am not knocking Christmas-Eve vigils, even vigils that end by 8:30 p.m. No humbug here. Singing Isaac Watts’ enduring verses of Joy to the World makes me feel positively high on holiday cheer, even when the singing is poor (as mine incontrovertibly is).

I have not yet set fire to anything when holding a holiday candle, although this year, just before the service, my pastor raced down the side aisle and his flowing robe fully swept across the flame I distractedly held. I did not take for granted this little Christmas miracle, which prevented this hard-working, unnoticing priest from suddenly catching fire.

But having said these good things, it might just be time to give our own Christmas celebrations the calendar equivalent of a bonus track or two. We treat the holiday the way vendors handle their folding tables at the end of farmers’ markets: after December 25, we fold up Christmas and stick it deep in the trunk of our regard.

Unsurprisingly, commercial impulses drive this attitude accepting of a “collapsible” holiday: we must pack away Christmas and the peace and good will it invites because we cannot delay the onrush of after-Christmas sales. And since the holiday fell on a Sunday in 2011, the new week further hastens that quick dispatching of Christmas. Stores opened early and the maelstrom of returns commenced. And although New Year’s came quickly, and children continue to enjoy holiday breaks from school, for most of us, it’s back to work, and to the routine. It’s back, too quickly, to what church calendars refer to as “ordinary time.”

We treat too much of our time during the year as ordinary, and are too willing to allow “common time” to return and reduce Christmas into a single day’s hurrah.

These days, Christmas Day itself is in jeopardy. Our local stores have regular hours, and for our family, it stands as solemn holiday observance simply to keep the cars in the driveway for the entire day. Yet even if we preserve it, making the day feel qualitatively different, that one-day luxury is not really Christmas. So why have we become so quick, when it comes to something awesome like Christmas, to settle for an abridged version?

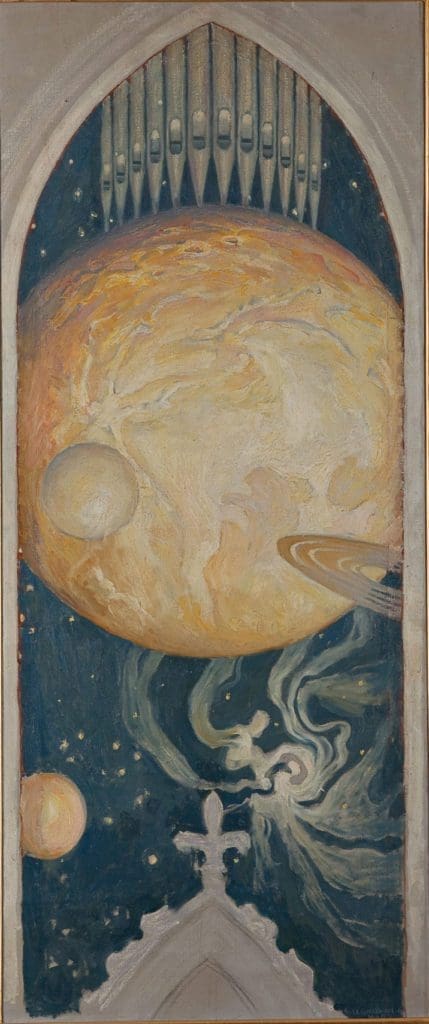

For many Christians, Christmas is a season, and I’m not talking about the hustling shoppers’ rave marketers call “the Christmas season” that begins on Thanksgiving Day and ends just before whenever your own family opens presents. The real season begins on Christmas morning, and it does not stop there. It’s called Christmastide. Most familiarly, it’s the “Twelve Days of Christmas,” with oddball leapers leaping, those five, massively drawn-out rings, and so on.

Those twelve days traditionally culminate today, on Epiphany, which celebrates the three wise men’s encounter with the Holy Family. The word literally means “to make manifest,” and the event signifies the newborn Christ being revealed to these distant travelers, and thus to the whole world. In the Anglican calendar, there’s even more Christmas beyond that, but Epiphany marks a festive high point. It can serve as a post-holiday time of comfort, too: many find meaning in this Epiphany prayer from Common Worship: “lighten our darkness now and ever more.” (Even better, we could take a page from the church calendar of Orthodox believers, whose Christmas season begins on January 6.)

We treat too much of our time during the year as ordinary, and are too willing to allow “common time” to return and reduce Christmas into a single day’s hurrah. I realize the workaday must necessarily prevail. Prince Hal, in Shakespeare’s Henry IV, says it well: “If all the year were playing holidays, / To sport would be as tedious as to work.” Holidays are the exceptional days, but they can last more than one day.

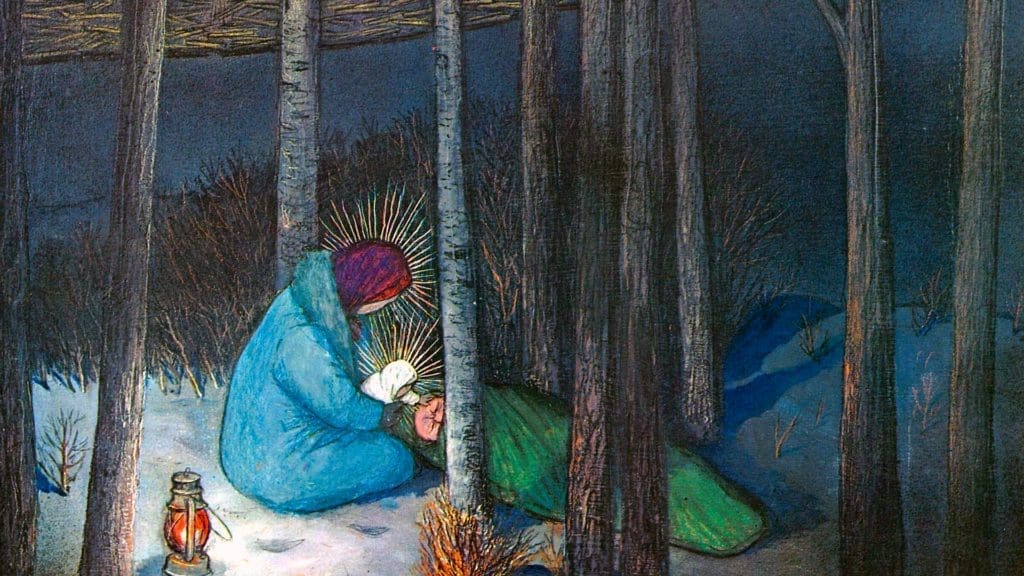

For those freshly interested in “still-Christmas,” then, those not yet ready to relegate the holiday to oblivion, you now have permission to remain merry, or hopeful, or simply to take a deep breath at long last. Perhaps the true spirit of Christmas can become more inhabitable now that gifts are given and turkeys cooked, the travels survived or the relatives gone.

And if you’re into it, then prepare yourself: the available holidays begin happily to pile up. Candlemas, which commemorates the presenting of the infant Jesus in the temple, occurs on February 2. It is so called because Simeon declared the child the light of the gentiles and glory of Israel, which led parishioners on this day to bring candles to be blessed. (In Chicago, where I live, that’s the time of year when everyone really needs a holiday anyway.) Or, in the pre-Vatican II Roman Catholic calendar, there was the Feast of the Circumcision on January 1, the eighth or octave day of Christmas. Which early Christians came up with this, marking a circumcision with a feast day?!

It is one of those paradoxes that, for Christians, makes all the sense in the world. During this ongoing Christmas season, we celebrate Jesus’ birth and its most modest circumstances (shepherds, swaddling clothes, manger), while simultaneously professing his victory over the world’s brokenness—this Man of Sorrows who eventually triumphed. It’s the paradox that made those wise men rejoice, as the King James Version has it, “with exceeding great joy.” It is worth celebrating a little while longer.