I

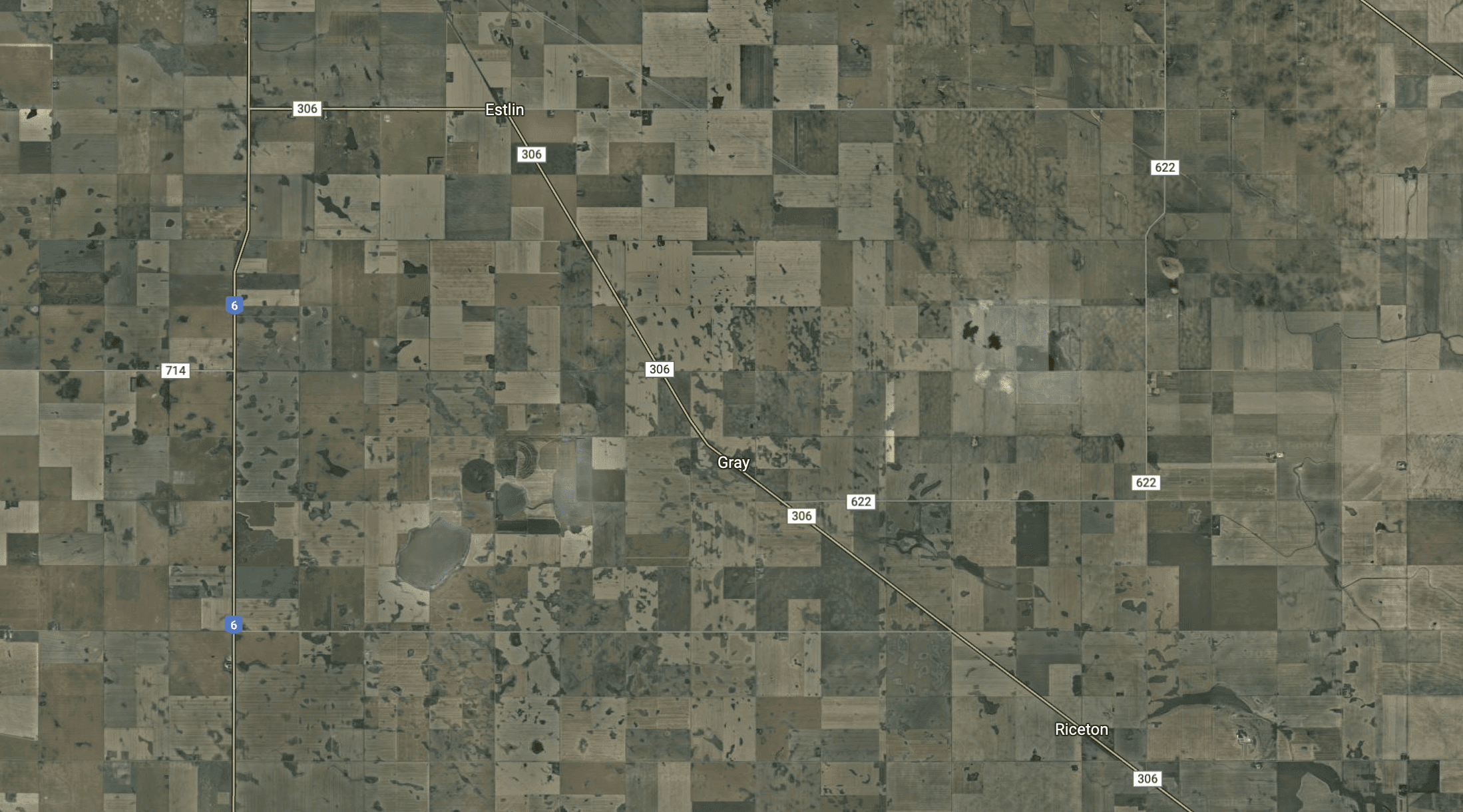

It’s easy to pick out Saskatchewan on a Canadian map. Almost perfectly geometrical, the province is unique in Canada—and one of a handful such political entities in the world. Like a tapered, baguette-cut emerald set in the middle of a gold ring, its north and south are comprised of the 49th and 60th parallels and its east and west bordered by the 102nd and 110th meridians west.

My kids, less inclined to think romantically of straight lines and right angles, call it the rectangle province.

It’s a benign example, but Saskatchewan, its southern patchwork of wheat fields in particular, is a perfect example of how states see the world.

Another example how the state sees the world—and its people—is provided by Mr. Beautiful Pants. Mr. Beautiful Pants is the real name of a real person whom I know and respect; a citizen of Canada who came to Canada from the Netherlands in the mid-twentieth century to forge a new life for himself and his family. And he did. A stalwart member of his church and his community, Mr. Beautiful Pants worked hard, paid his taxes, got married, had kids, and is now the grandfather of a whole generation of Canadian citizens who go by the name of Mooibroek.

That a whole generation of Canadians who work, live, and succeed under the moniker Beautiful Pants is an identical, but more absurd, example of how to see like a state.

I say absurd not because the name Mooibroek is worthy of ridicule. Those who know Mr. Mooibroek and his family know that he has made it a name worth of deep respect. The last name is absurd in the second meaning of the word: it “has no rational or orderly relationship to human life.”

The name—likely given by a French bureaucrat during Napoleon’s brief interlude in the Netherlands for the sole purpose of rationalizing the state’s tax rolls—is a non sequitur. What hath the flesh-and-blood Mr. Mooibroek and his family to do with beautiful pants? Nothing. What hath the 110th west meridian to do with the daily activities of citizens of Lloyminster? Not a whiff.

So why are they there?

State-vision

They are there because they help make places and people legible to the state. And “legibility” according to James C. Scott is the “central problem of statecraft.” For Scott, a professor of political science and anthropology at Yale, this problem has always been present in politics, but it is only with the development of modern tools that its true scope can be felt.

Straight borders, straight fields within those borders, and last names, have no rational relationship to human life or the way the world works except insofar as they enable the state to efficiently provide for “the pressing material interests of rulers: fiscal receipts, military manpower, and state security.”

A border consisting of thousands of islands and uneven coastline is difficult to monitor, let alone defend (just ask the Canadian coast guard in Nunavut!). Accurately taxing millions of people, a good number of whom share first names is an impossible task; in fact, accurately taxing millions of people with both first and last names is still very difficult. Best to just give everyone a number—social security, social insurance depending on your country—and be done with it.

These things, in themselves, are not necessarily problematic. But, as Scott shows in painful detail, states have rarely been content to exercise their core functions—or even benign non-core functions.

Effective public administration according to a legible grid is necessary for proper pursuit of public justice. But wedded to three additional elements, the drive for legibility can be—as Scott shows through detailed and wide ranging case studies of German forests, Irish potato fields, Paris neighbourhoods, Brasilia, forced villagization in Tanzania—catastrophic for humans and their social and natural environments.

The first of these elements is high-modernist ideology, which Scott describes as “a faith that . . . is uncritical, unskeptical, and thus unscientific in its optimism about the possibilities for the comprehensive planning of human settlement and production.” This planning tended to focus on using “state power to bring about huge, utopian changes in people’s work habits, living patterns, moral conduct, and worldview.”

The second is an “authoritarian state that is willing to use the full weight of its coercive power to bring these designs into being.” Scott notes that both the right and the left have produced their share of catastrophes, but note “there is no denying that much of the massive, state enforced social engineering of the 20th century has been the work of progressive, often revolutionary elites.” The reason for this is that “progressives come to power with a comprehensive critique of existing society and a popular mandate (at least initially) to transform it.”

The final element—of key interest to Cardus readers—is “a prostrate civil society that lacks the capacity to resist these plans.” The state, which is an important but limited institution, must be kept in check by a robust civil society. When that civil society is missing or weak, the state, possessing a “bulldozing state of mind,” will (sometimes literally) run roughshod over society.

In short, to see like the state is to be myopic. This myopia views geography, people, their customs and traditions in a way that “severely brackets all variables except those bearing directly” on the state’s interests of revenue, security, and order.

Unstable Architectonic Visions

As noted, state-vision is not inherently destructive. It is only when the state’s vision is so propelled by its own interest that it fails to align with the interests of its citizens. After all, a functioning state administration—aided by a legible society—is also capable of great good. Scott cites public health initiatives such as clean water and vaccinations as examples of the benefits brought by such vision. He also writes with a clear eye fixed on the often unjust and undignified treatment of humans in illegible societies. But, despite these caveats, he maintains that state-vision of the type described above “is not, and could not ever be realized in practice.”

Why? Because it fails to consider the complex, multi-faceted character of human life, and the incomprehensible (to states) ways in which humans live and order their lives. In other words, the programs of state intervention are (to adapt a metaphor from Scott’s study on rationalizing forestry) “living off, (or mining) the long-accumulated soil capital of the diverse, old-growth forest that it had replaced.”

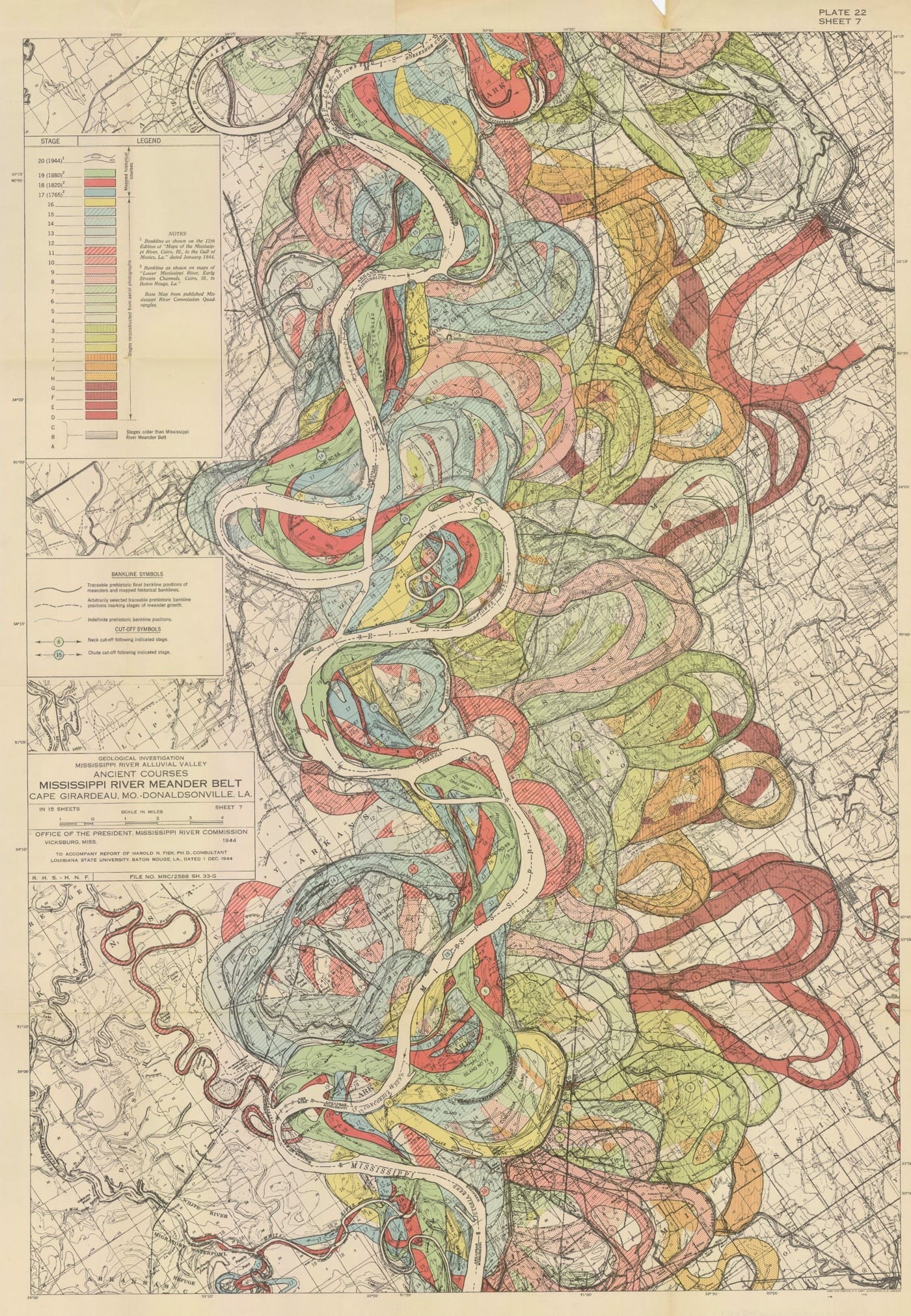

These architectonic visions attempt to supplant mētis, or the knowledge that comes from daily practice and daily life in a particular, local place and community. Scott’s definition is even better: “knowing when and how to apply the rules of thumb in a concrete situation is the essence of mētis.” It is a knowledge more likely found in a craftsman than a planner. The technical knowledge of central planners will inevitably fail because, of the three acts necessary for the making of a good life—consideration, creation, and an encounter—it fails to encounter, or even deliberately brackets, the realities, the practices, and dare I say it, the liturgies, on the ground.

Mētis is less the type of knowledge held by the US Army Corps of Engineers, and more of that needed by the steamboat captains in Mark Twain’s Life on the Mississippi (which Scott cites). You need local knowledge and practice if you’re going to get your customers down the river safely. A river like this cannot be navigated by book or universal principles without disaster for the ship and its passengers:

The Ophthalmologist’s Diagnosis

This book is extremely well-argued, and deserves to be on the reading list of everyone who wants to understand the effects that modern states have—for good or ill—on their citizens and communities. Some might argue that one is not changed by being seen—seeing is done at a distance and effects no change on the object, right?—but Scott presents enough evidence to convince the reader that the state’s vision, “by a kind of fiscal Heisenberg principle, frequently has the power to transform the facts they take note of.”

How then, do we evaluate the transformative effects of state-vision? How do we answer the excellent question posed by Scott himself: “To the degree that such thin maps do manage to impress themselves on social life, what kind of people do they foster?”

Scott’s diagnosis is bleak. State vision creates a

This neurosis is true across a host of institutions, including the state itself. Looking at these characteristics, and then comparing them to, say, voter turnout, the quality of parliamentary debate, the health of civil society, low birth rates, or even the state of workforce participation in our North American context, one has to ask: Are we being burnt by the magnifying glass of state-vision?

Of course these bleak stats must be placed alongside other statistics which suggest that we are living longer, have higher incomes, and are more educated. But, it is, I think, fair to question whether these are sustainable or if they are congruent to the type of results that occurred when German foresters first rationalized their forests and introduced new species that would produce mass quantities of lumber. The first century was a tremendous success, but it was only in the second century that the full scope of the poverty of the soil was revealed. America is 237 years old. Canada is 146. Are we “living off (or mining) the long accumulated social capital” of our nations?

I think we might be. I’m not an alarmist by any means, and these trends can always be reversed, but there are three examples that I would offer in defence of this claim. The first is the state of education in Canada and the US, the second is our understanding of markets and the economy, and the third is the state of religious freedom and discourse in our two countries. The combined relationship of these factors with our state supports, I think, those who are concerned about the long-term prospects for prosperity and peace.

An example from the institutional point of view of schools illustrates the point well. Education, and the shape of the schools that provide it, is one of the most contentious issues in Canadian and American public debate. While there are notable—and hopeful—examples to the contrary, both countries tend to view education, and therefore schools, as being in the service of the state and its goals. Both tend to see schools as being at the service of the economy and the state. Don’t believe me? Listen to recent Canadian debates about education in the trades, or consider the size of Harvard’s endowments and the culture that has grown up around America’s elite schools. It is a rare occurrence indeed to hear a politician speak of schools as places of character formation or of the deepening of wisdom. Instead, they are training grounds for the modern economy. Where deeper questions about the purpose of education are asked, they too are posed with a view to the interests of the state. Where Canadian schools—usually religious schools—attempt to maintain their freedom from central state schemes, they have faced the full brunt of the coercive power of the state. The same fate has befallen other religious institutions that attempted to work outside of the directives of the state in America.

Scott notes that what state “designers had in mind . . . was to design a shape to social life that would minimize the friction of progress.” But the difficulty with this resolution “is that state social engineering was inherently authoritarian.” In these cases above, the state attempts to forcibly smooth the friction posed by religious institutions—it starts with the schools, but recent decisions surely pave the way for churches to come next—and their unique perspectives, gained from thousands of years of practice, habit, and thought.

Could it be that liberalism, rather than a check on the power of the state (as Scott suggests it is), is actually a regime unsuited to the deep complexities of human life?

Seen in this light, might the stats of higher living standards and increased longevity be better seen as themselves in the interest of a state that prefers its citizens fat and content? Might we be living in, as the great political theorist Sheldon Wolin aptly puts it, the Great Satiety?

The Ophthalmologist’s Prescription

It’s no surprise that Scott’s prescription for state-vision is a greater appreciation for mētis in all institutions. He is, interestingly enough, calling for a return to the old-fashioned notion of state-craft. Governance that shows concern and care for the institutions and people within the state, rather than an intensive (that term is Jonathan Chaplin’s) imposition of the state into all areas of life. Families, schools, businesses, the land should be considered on its own merits, and the practices inherent to these institutions should be recognized, and when challenged, in a way that respects their traditions, histories, and insights. He states that

In other words, he recommends that the state junk its old glasses and put on a pair of multi-focal glasses as it goes about its business of making laws and executing justice.

This is all music to the ears of those familiar with Christian social thought. It is recognition that civil society, even when it serves a public purpose of, can never be reduced to the state’s purposes, even the purpose of restraining the state.

It is notable, however, that Scott spends very little time speaking about religion and religious institutions in his text. The absence is so jarring because the book is shot through with examples of the state’s unsettling of social habits, aesthetics, rhythms, and fundamental beliefs of citizens and their institutions. This book is, as our beloved editor would likely note, a giant allegory for the replacement of certain cultural liturgies with others.

If one were to quibble with the book it would be that, in searching for prescriptions, Scott overlooked the massive dose of medicine that has cured—or at least mitigated—some of the worst symptoms of state-vision: religion. While he could also justifiably point to cases where it has exacerbated the symptoms, religion, and particularly Christianity, has been a thorn in the side of the grand scheme of many a state intent on creating the world in its image—those long gone, those recently deceased, and those still with us. Why? Because it is the embodiment of metis—the practices of the living, not the dead, that has reflected for thousands of years on how to make the state work for man, not man for the state.