W

When one thinks about locations that evoke pure sublimity—spaces that unveil the eerily beautiful combination of the universe’s vastness and human finitude—Target is probably not on the list. However, during the global pandemic, one became deeply grateful for any opportunity to experience atmospheres that were not home. In the wake of Covid-19, visiting different architectural spaces struck many as novel for quite some time. But what do these experiences of different atmospheres teach us about our lives? And more importantly, what might they teach us about worship, sacredness, and God’s presence in material environments?

The Covid-19 pandemic struck while I was in my second semester of Duke Divinity School. As a result, I found myself confined to a tiny apartment with a suffocatingly low ceiling. My courses had moved to virtual platforms, and so I, like many students, endured hours (and sometimes days) without real human contact. I even ordered groceries for curbside pickup. After the semester ended, I decided to move back home with my parents. They provided much-needed personal interaction. However, they had recently downsized into a new home, and we were now living in a rather small house. I was thus back to a truncated material environment conditioned by low ceilings. To be clear, I actually liked both my apartment and my parents’ house. In a pandemic-free world, I would have been perfectly content; but months spent in narrow spaces had germinated my cabin fever.

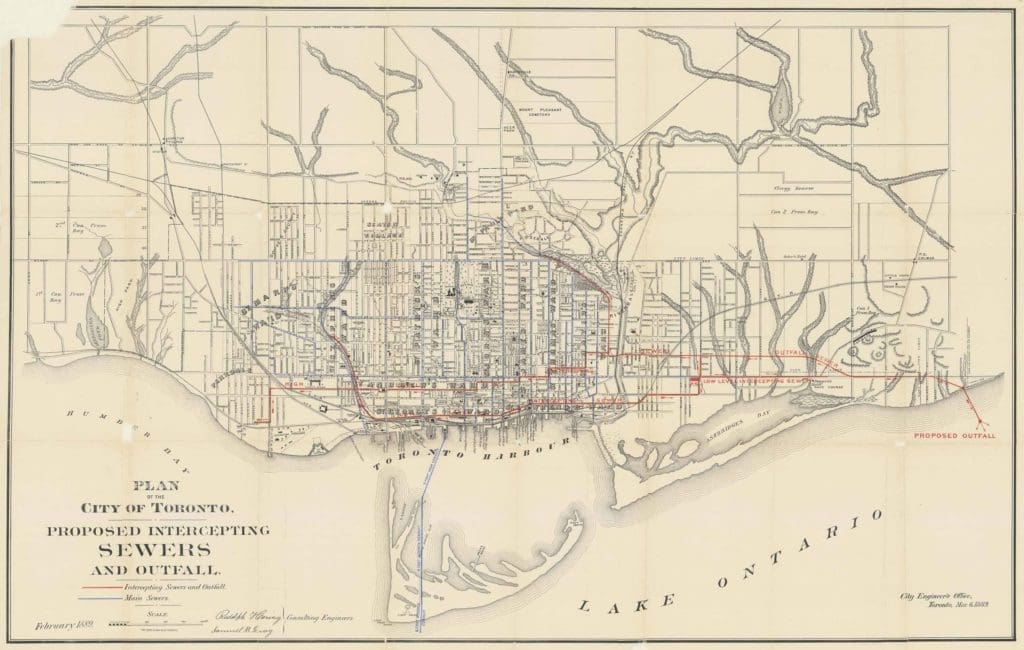

When the pandemic waned and vaccines became available, my mom and I ventured on a quest: in-person grocery shopping at Target. It was our first time in months, and it suddenly seemed dangerous and foreboding. As I cautiously traversed the aisles like Theseus through the labyrinth, I looked up and beheld a numinous vision: a raised ceiling. I gazed on the levitating light fixture and seismic ceiling tiles like the man in Caspar David Friedrich’s famous painting, Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog.

I had a more conventional spiritual experience returning to in-person church services. While in Duke Divinity School, I worked as an intern for the Congregation at Duke Chapel. The congregation worships each week in the large Gothic cathedral located at the heart of Duke University’s campus. Duke Chapel is perhaps my favourite building in the world, and when the doors had to be locked during the pandemic, I felt as if a piece of my soul was missing. But as time moved on, the doors once again opened, and I was able to return to the sacred space I loved. I cried tears of elation as I once again could walk through the aisles and be bathed in the kaleidoscope of colours pouring in through the stained glass. I gazed with admiration at the complexity of wood carvings surrounding the choir’s chancel. The vibration of the organ music reverberated through the stone atmosphere, shaking my entire body. And, true to form, I spent quite some time staring at the intricately carved arches along its ceiling, which were more than double the height of Target!

Both of my stories illustrate something called “atmosphere,” a phenomenon easier to grasp through experience than to articulate with theory. Atmosphere is an affective surplus within space that is generated by a sentient creature interacting with a material environment. Through the staging of the material environment around us, we can generate moods, affects, and ways of inhabiting space. Though we might use other words such as “mood,” “ambiance, or “vibe,” most of us are aware of the presence of atmosphere. We are conscious of how uncomfortable it is to sit inside a dentist office with its swirling, drilling noise, unpleasant odours, and burning fluorescent lights. Conversely, we are aware of the tranquil atmospheres of a well-cultivated botanical garden or the rapturous delight of an astounding cathedral. Atmosphere is a key component of how we navigate through life because it permeates the architectural spaces and material environments in which our lives take place. Like an astutely designed stage in a theatre, atmospheres can be cultivated toward specialized ranges of emotions and responses. They can influence us toward feeling relaxed, safe, excited, fearful, or, in the case of shopping malls, ready to buy something.

As I cautiously traversed the aisles like Theseus through the labyrinth, I looked up and beheld a numinous vision: a raised ceiling.

Now that the world around us is once again open, many are recognizing the importance—dare one say, the necessity—of atmosphere. Atmospheres help us become embodied and embedded within our material surroundings. In this sense, they can be invoked toward good ends, such as encouraging relationships, fostering peace, and giving people experiences of art and beauty. The power of a well-staged atmosphere to foster desire can likewise be used toward commercialism or, as in the case of fascist architecture, to prompt fear and intimidation for an aggressive nationalism. Thus, by understanding the reality of atmosphere, one can gain greater agency regarding how to stage one’s material environments according to one’s goals and values. Likewise, one can be aware of how atmospheres might be weaponized to devious ends.

Though not everyone gazes at the ceiling in Target with the mystic rapture of Moses encountering the burning bush, most people can cite instances of being “caught up,” astounded, awestruck, overwhelmed, or enchanted by beautiful atmospheres. For many, such experiences happen in sacred spaces such as churches, cathedrals, and chapels. If one interviews enough people about why they love their church, answers will often include facets of the atmosphere: the stained glass, the music, the icons, the architecture, the incense, and especially the warm and welcoming sense of community with others. The spaces in which we worship are vital to the practice of worship itself.

Certainly not all church atmospheres are the same. The holy sublimity produced by a Gothic cathedral cannot be emulated by the wooden chapel of a small, rural town. However, both of these atmospheres can be beautiful, and both spaces can be means used by God to bring us deeper into faith. Atmospheres are created, cultivated, and maintained by sentient agents, and certainly the Holy Spirit is the most important agent within the creation of sacred atmospheres, using the material means to draw us closer to God, the body of Christ, and even creation as a whole.

Though not all church atmospheres are the same, there are some common virtues of faith and dispositions of discipleship that churches should seek to encourage as they stage their atmospheres. It might seem like I am asking too much of atmosphere, but a sacred atmosphere ought to encourage one’s love of God, love of neighbour, and love of all creation. The scriptural warrant for love of God and love of neighbour comes from Mark 12:30–31, in which Christ says, “You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your mind and with all your strength.’ The second is this, ‘You shall love your neighbor as yourself.’ There is no other commandment greater than these.” The imperative to love all creation comes from both the Old and New Testament. In Genesis 1–2, humanity is tasked with being stewards and caretakers of God’s creation. Churches must therefore cultivate and encourage a way of being stewards in the world that treats environments, plants, and animals in accordance with the promised future reality of God’s redemption that is breaking through into the present all around us.

Atmosphere is a key component of how we navigate through life because it permeates the architectural spaces and material environments in which our lives take place.

Initially, this all might sound like vague, ethereal platitudes. But the imperatives to love God, neighbour, and all creation present vital questions for how churches stage their atmospheres. For example, can a church’s atmosphere be considered truly loving of neighbour if it has not made proper accommodations for people with disabilities? If the space itself is not accessible to wheelchair users or those using walkers, then the church is not properly loving its neighbour. Perhaps the space itself is accessible, which is a great thing, but one must also ask if the atmospheric staging encourages human connection and the fostering of community. Is the lighting bright enough to see those with whom we are meant to develop a community, or is it so dark that one cannot see the others with whom one worships? The latter case can result in fostering a more privatized, individualistic experience of worship, which is not the picture of the church envisioned by the authors of Scripture.

Finally, the call to love all creation challenges churches to think about whether the building is being used in ways that honour the environment. Beyond discussions around clean-energy use, the need to love all creation should also inspire churches to consider how the cultivation of gardens, outdoor prayer spaces, and indoor plants creates an atmosphere that stewards creation well.

It has been almost two years since I was flabbergasted by those impossibly high ceilings in Target, and I have shopped in Target several times since then. Admittedly, I’ve yet to respond to any atmospheric feature of their store with more than mild intrigue. But the way the morning sun illuminates the stained-glass images in my church still fills me with awe each Sunday. Though Target no longer holds the same sublime impact it did in the wake of my sheltering in place, sacred spaces still fill me with gratitude for the beauty and glory of God. Atmospheres that encourage love for God and create an environment for hospitable Christian community fill me with thanksgiving and a love for life that make it hard to do anything but worship.