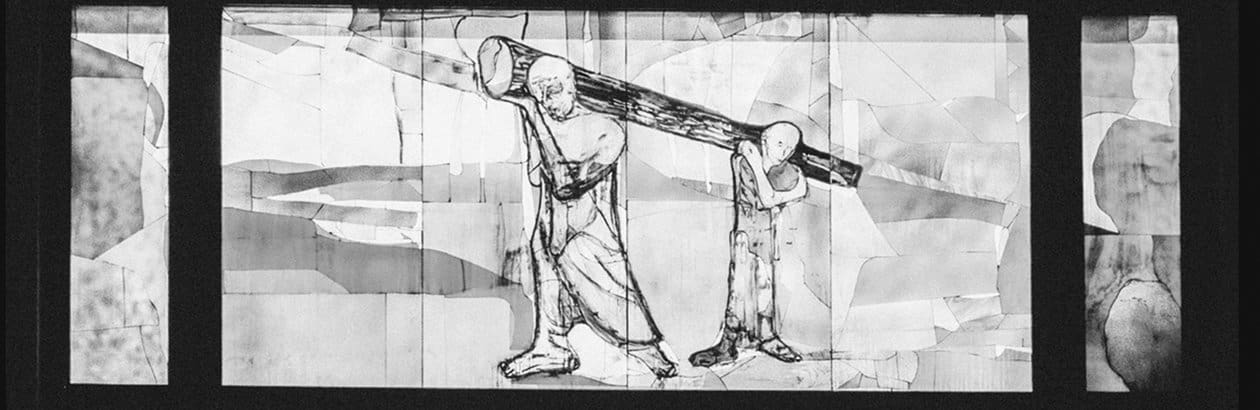

Remembering is complicated. But one thing is certain: when you try to recollect something, you enter like Jacob into the confessional with God. Whether you’re remembering a major historical episode or a minor personal experience, you are wrestling with the Truth of what took place at a certain a time, and you are by nature a deceiver.

We tend to sweeten past successes and happy moments, to preserve them intact. We tend to blame others for old failures and ongoing troubles, because we find it hard to admit we ourselves may be complicit in evil. We are disposed to play heroes, or worse, to judge ourselves to be innocent scapegoats. Since life is normally a mixture of good and evil, memories and telling the history of things are apt to be a confusing mess of slanted, untrustworthy recollections.

A drastic contemporary solution to this problem of falsifying memory is to pretend we have next to no historical baggage. A prevalent pragmatistic spirit also helps cultural leaders and followers alike to practice cultural amnesia. We put traumatic past events like the nineteenth-century slave trade, the Great Depression, the atrocities of Dachau and Auschwitz in museums for storage and occasional ceremonial visits, and we barefacedly focus all our attention and energy on solving our current problems. It’s the future that counts!

Such unawareness of how God lets the past inhere the present prompts us to make superficial, self-exonerating, jump-start judgments: Generals try to end war between long-standing ethnic animosities by making smart bombs that kill with greater precision; leading entrepreneurs mean to reduce the number of poverty-stricken workers by giving the corporate market free rein, which only promotes survival of the fittest few. That human hate is not mitigated by technology and that greed outlasts benevolence are realities worth remembering.

Reliable remembering, in my judgment, will have a wrestled, repentant character and carry a redemptive quality and patient spirit, whether it be personal memory, the conscience of an institution, or the company of God’s adopted children.

When I remember well the good events in my lifetime, I am thankfully overwhelmed in recognizing the role others close to me played in their fruitfulness. When I remember well the evil of which I am guilty, I cringe, without excuses, shamed, confused, while pleading with my Lord somehow to overturn its bad consequences, maybe even by my remedial service.

When a nation recalls its complex history, it needs to confess explicitly its nation-forming sins as well as blessings, and cast the whole project as an unfinished development to be driven further by the norm of restorative justice— there are deep wounds still needing to be healed before congratulations are passed around about accomplishments.

When God’s people as church tell what happened before its current riven unity, remembering its Pentecostal institution, the course of faithful witness, heresies, recurrent hypocrisy, martyrdoms, crusades and reformations, enduring diaconal ministries, a holy remnant, it boggles one’s consciousness. The pockmarked history of the communion of saints past, present, and forthcoming will be redemptive if its story invigorates one’s gratefulness to be still wrestling at Jabbok. Church history is not a tale of woe or of victory, but is a story that prompts a community of persevering sinful saints to live in patient, certain expectation of the risen Christ’s return to bring a final shalom.

The hardest matters to remember redemptively, I find, are the times when you have been physically and emotionally abused or had intimate secrets betrayed by someone else. Only God has the option of forgetting what is on the historical record. We people, however, are enjoined to bathe our remembering in forgiveness, which entails, I believe, laying down your life, that is, offering up to the evildoer your “rights” to punishment. Followers of Jesus Christ—because we shall be everlasting!— are called to take hold of God and pull for the grace to mimic the Eucharist: reclaim the dread memorable past event by reenacting consciously your survival of the curse as an opening to be grateful to the God of Jacobs to serve the enemy.

All true remembering will bless you—violated person, Holocaust survivor, persecuted church—with a telltale limp.