I

In 628 the Roman Empire was jubilant. The Romans (as they called themselves; we tend to know them as Byzantines) had, for the best part of a century, faced a rival in the east, but in a surprisingly short period of time, that evil empire had been defeated and was now disintegrating. The moment of triumph was short-lived. Within a few years, a new, unforeseen, hostile force had appeared on the empire’s southeastern border, and within a few decades it was threatening the imperial capital. The effect was shattering. Euphoria turned to disarray and soul-searching. How, and why, had this happened?

This being a more primitive time, the answer was obvious: God. “These people came by God’s command,” wrote the monk John bar Penkaye. “The Lord in his wrath . . . will stir up kings and mighty armies . . . [and] nations will be subjected before the marauding people,” a homilist bellowed in the 640s as the Arab armies marched through Palestine. Everything could be explained as divine punishment or, at least, divine permission. No surprise there was an apocalyptic smell in the air, and that writer after writer claimed they were living at the end of history. “The end-times have arrived,” Ephrem the Syrian lamented.

Such explanations, it is fair to say, are not popular today. “In old times,” writes the cliodynamic historian Peter Turchin, “such major calamities were taken as a sign that God had turned away from the ruler. . . . Today, we tend to think in more materialistic terms, blaming the government for dysfunction and failure to take effective steps to stop the epidemic.”

The manner in which historians of late antiquity (and, indeed, many other times) invoked divine judgment as a decisive factor in historical events is one of the things that marks them off from us wiser moderns. When historians today explain the fall of European empires in the twentieth century, or the impending decline of the American one in the twenty-first, they rarely deploy the language of morality and theology. Right?

The New Age of Empire

Popular interest in empire tracks a parabola. In the nineteenth century, discussion of empire and imperial topics was common. It fell steadily through the twentieth century, hitting a low point in the decades after European decolonization, but began to rise again in the 1990s and is now at its former height.

Professional historical interest tracks a similar path. The historiography of British imperialism was once essentially practical, mining the past for useful insights. As European empires vanished, so did the need for imperial instruction. Some argued that this made the discipline ripe for dispassionate evaluation. The editor-in-chief of the five-volume Oxford History of the British Empire, published in 1988–1989, remarks in his preface to the series, “The passions aroused by British imperialism have so lessened that we are now better placed than ever before to see the course of the Empire steadily and to see it whole.” There was little sense that the subject was about to explode. As it happens, the fuse had already been lit. In 1978 Edward Said’s seminal Orientalism was published, helping to popularize the discipline of post-colonial studies. A new perspective, and with it new and often opaque concepts and vocabulary, at first bewildered and then revitalized the field.

What really transformed it, however, was the emergence of an American imperial mindset around the turn of the millennium. “What’s the point of being the greatest, most powerful nation in the world and not having an imperial role?” asked the neo-conservative thinker Irving Kristol, somewhat rhetorically, in 2000. The ninety-page report Rebuilding America’s Defenses, published in 2000 by the neo-conservative think tank Project for the New American Century, argued that US military forces needed to be able to fight and decisively win multiple, simultaneous major wars and to perform “constabulary” duties across the world. It was, in effect, a blueprint for a new Pax Americana, which is what many called it.

George W. Bush had repudiated the label of “empire” during his election campaign, but when an unforeseen and clearly hostile force committed mass atrocities on American soil on 9/11, it was not only Bush and the neo-cons who embraced an imperial role for America. “The 21st century imperium is a new invention in the annals of political science,” wrote Michael Ignatieff in the New York Times, “an empire lite . . . whose grace notes are free markets, human rights and democracy.”

A decade and a half later, it was the UK’s turn. The Brexit referendum kindled a ferocious debate about Britain’s past and future role in the world, during which there was much discussion about the purpose and potential of the Commonwealth and the Anglosphere, and the UK’s role in creating, nurturing, and reinvigorating both. Moving closer to the present, Vladimir Putin invaded Ukraine in his long-standing desire to recapture a “Greater Russia”; Xi Jinping said that Taiwan was part of “China’s sacred territory”; and Donald Trump declared, in his second inaugural address, that America would now “once again consider itself a growing nation—one that increases our wealth, expands our territory.” Empire is everywhere.

Crucially, however, it isn’t just the story of empire—its objectives, strategy, and implementation—that is back. So is the question of its morality. This has never not been important, of course, not least because it is vague and marshy territory. Almost everyone who writes on empire acknowledges that the term is sprawling and possessed of almost no analytical rigour. Early in his book Empireland, Sathnam Sanghera says more or less the same thing about the British Empire: “Britain’s relationship with its colonies varied across the globe and over time. . . . The culture and tone of empire varied wildly during its history. . . . Empire was never unanimous. . . . There was no clear motivation for the establishment and development of empire.”

It isn’t just the story of empire—its objectives, strategy, and implementation—that is back. So is the question of its morality.

These things being so, offering a moral evaluation of (an) empire is a fool’s errand. And yet a cursory glance at the relevant shelf or table in any bookshop reveals many fools on many such errands. Not only is moral evaluation of (the British) empire a flourishing genre, but it is one that has already come to a strong and clear conclusion. The selection of books in my local Waterstones—Legacy of Violence, Britain’s Slave Empire, Inglorious Empire, and so on—is highly instructive. If, as the former high court judge Jonathan Sumption has written, “it is hard to think of any human institution enduring for centuries of which it can seriously be said it was all good or all bad,” then recent publishing history suggests that the British Empire is an exception to the rule.

The “Serious Shit” of Ethics and Empire

Into this atmosphere Nigel Biggar, then regius professor of moral and pastoral theology at the University of Oxford, launched a project in 2017 titled Ethics and Empire. Biggar’s project was intended “to develop a nuanced and historically intelligent Christian ethic of empire”—the Christian element was, significantly, subsequently dropped—in order to “enable a morally sophisticated negotiation of contemporary issues such as military intervention for humanitarian purposes in culturally foreign states, the cohesion of multicultural societies, and settling imperial pasts.”

The response was not immediately encouraging. “OMG, this is serious shit,” tweeted Cambridge University’s Priyamvada Gopal. “We need to SHUT THIS DOWN.” Other responses were equally hostile, if less vigorous. “Professor Biggar has every right to hold and to express whatever views he chooses,” began an open letter signed by fifty-eight academics, before going on to say, “but his views on this question, which have been widely publicised at the Oxford Union, as well as in national newspapers, risk being misconstrued as representative of Oxford scholarship.” Presumably Biggar had every right to express his views, just so long as it wasn’t in print or in public debate.

A second letter, now signed by about two hundred academics from around the world, requested Oxford withdraw its support from the project. Oxford’s Centre for Global History duly announced that it was not involved with the project. The project’s co-leader stepped down. There were delays. Biggar persisted, the project finally got underway, and six years later he published his own book on the British Empire, titled Colonialism: A Moral Reckoning.

The book’s path to publication was no more straightforward than the project’s had been. Despite his editor praising the book, Biggar received an email from the head of special-interest publishing at Bloomsbury telling him that they had decided to postpone publication (indefinitely) because “we are of the view that conditions are not currently favorable to publication.” Pressed for clarity, Bloomsbury “released” Biggar from his contract. William Collins quickly picked up the book, which was published in 2023. To date, it has sold over sixty thousand copies.

Given this messy and difficult birth, it is unsurprising that the book received mixed reviews. The commendations were glowing, as commendations are (or usually are: it’s a real shame more authors don’t take a leaf from the literary critic John Carey, who, on the paperback cover of his book What Good Are the Arts?, quoted the art critic Matthew Collings, who described it as “taxi driver bollocks”). Press reviews were more negative. While those that praised it did so for its balance, others insisted that Biggar’s moral reckoning ought to have reckoned more with racism and genocide. Reviews ranged from the loosely critical to the relentlessly hostile. A postscript added to the paperback edition responds to ten such reviews, none of which quite reached “taxi driver bollocks” levels, albeit some were not far from it.

Evaluating these verdicts and offering a reckoning on Biggar’s reckoning is far from straightforward. Colonialism is certainly more impressive than many of his critics allow. The idea that it is a straightforward defence of empire is ludicrous, as is the idea that Biggar is deaf to its sins. He is, for example, clear-eyed about the grotesque inhumanity of the slave trade, and he begins his conclusion with a list of the evils, both intended and unintended, of British colonialism, citing in addition to slavery the spread of devastating disease, economic and social disruption, displacement of natives, failures of colonial governments to prevent settler abuse and famine, racial alienation and racist contempt, policies of wholesale cultural suppression, miscarriages of justice, unjustifiable military aggression, the indiscriminate and disproportionate use of force, and “the failure to admit native talent to the higher echelons of colonial government on terms of equality quickly enough to forestall the build-up of nationalist resentment.” All these evils, he concludes, are lamentable and “where culpable, they merit moral condemnation.”

This is, one would have thought, a list to satisfy even the fiercest critic. But the problem for such critics was that Biggar doesn’t just offer a critique of empire. He also makes a strong case for the good that the British Empire delivered. Later on in the book’s conclusion, he credits to the empire the abolition of, and subsequent attempt to suppress, the slave trade; the promotion of a worldwide free market; the creation of regional peace by means of imperial authority; the representation of native peoples “in the lower levels of government”; attempts “to relieve the plight of the rural poor and protect them against rapacious landlords”; a civil service and judiciary “that was generally and extraordinarily incorrupt”; the development of “public infrastructure, albeit usually through private investment”; the dissemination of “modern agricultural methods and medicine”; and resistance to fascism.

As far as I am in a position to judge, this seems to be a reasonably balanced assessment. I have written elsewhere on some of the nuances of this reckoning, not least the slightly obscure question of what vantage point Biggar adopts to take his moral reckoning. However, what I want to emphasize here is not so much the question of whether he is right or wrong but what the whole, intense fury around his book and his subject tells us about where we are as a culture today. Detailed, powerful, and controversial as Biggar’s book is, it is actually the strength—the passion, the anger, the sense of “OMG, this is serious shit”—of the response it provoked that makes it such a significant cultural artifact, revealing much about our morality, theology, and civilizational insecurity. That passion is highly instructive and can, I think, be helpfully analyzed through the lens with which we started.

Back to Byzantium

We do Byzantine chroniclers, historians, and theologians a disservice if we think they imagined that “God did it” (or “God allowed it”) was really an explanation for the rise of Islam and the near collapse of their empire. The God of that empire had long been the God of the Hebrew prophets, who judged the nations according to justice. He was a God who, it was claimed, was both good and trustworthy, rather than malign, arbitrary, or indifferent.

In reality, “God did it” was a cipher for a more complex set of explanations that integrated human agency. “On account of our sins they have now unexpectedly risen up against us,” wrote Sophronius of Jerusalem in a synodical letter in 634 as Arab armies took his city. It was because of “our countless . . . grievous offences,” he repeated in a homily on the nativity delivered the same year. God allowed this to happen, remarked John Moschus in his book The Spiritual Meadow written in about 640, in order “to discipline our wickedness.” The Saracens went forth from their own land, wrote the monk Anastasius of Sinai in his Edifying Tales, “according to God’s righteous judgement.”

Sin, wickedness, offences, (un)righteousness, judgement: such concepts are unlikely to strike modern historians as any more credible than the blunt “explanation” that God did it. But to Byzantine Romans struggling to come to terms with recent events, these ideas were helpful, and potentially salvific.

Belief in God’s final sovereignty affirmed that there was an order to history, that human affairs were not simply a matter of might, but that there was a moral orientation to the world. History was not just an ancient pile of rubbish blown around by the wind. It had a direction. Moreover, belief in a God who cared about humanity (and, in particular, the faithful) meant that history had a direction with which humans could cooperate, or that they could resist, if they chose. The idea that divine sovereignty was connected, however obscurely, to human belief and behaviour afforded humans some small agency, a sense that they could shape the course of events, even (especially) when that course looked helpless. Understand the pattern of sin, failure, and righteous judgement and you would understand not only the past but also the way of the future.

There is a good argument that the incursion of the Arab armies was the point at which the Roman Empire of late antiquity changed cultural direction. The empire had experienced trauma on multiple recent occasions, but the rise of Islam was something different: a complete surprise, astonishingly rapid, and possessed of a spiritual confidence and theological coherence that made it more troubling than mere “natural” disasters.

Theologians had talked of a kind of “imperial providentialism” since the time of Constantine, a logic by which the emperor’s personal piety and his role as guardian of orthodoxy prevented, or permitted, military defeat or other forms of collective trauma. But, according to Byzantine historian David Gyllenhaal, this kind of providentialism now gave way to what he calls “pastoral providentialism,” a logic more in keeping with those Hebrew prophets who had held the people, rather than just the king, as accountable for the moral failings of the nation. God’s anger, and with it the course of history, might still be altered, but it would take collective repentance, through penitential ceremonies, petitionary prayer, and moral reform.

The wars over history, empire, and colonialism that have flared up so viciously of late are about the future as much as the past.

The shift helped speed the ongoing Christianization and scripturalization of life in late antique culture, in which peasants were disciplined out of their persistently pagan habits and elites saw the plot of imperial life grafted firmly onto the biblical narrative. So-called rebuke homilies flourished, in which preachers admonished their flock—directly, severely, starkly—for the sins of their past and warned them of the need to confess, repent, and make restitution, for fear of further divine judgment.

Much of this penitent energy was directed to the visual representations of what the Romans held holy. Within about a decade of the 717 Arab siege of Constantinople, Emperor Leo III threw his support behind the arguments against the production and veneration of icons of Christ and the saints, and holy images started to be removed, defaced, and destroyed. The dispute would last over a century, waxing and waning between those who sought to retain sacred images in worship and those who now saw them as symbolic of the empire’s disastrous theological and moral failings. The combination of history, morality, and images proved to be combustible.

Rebuke Homilies and Repentance

Many people, including Biggar, have pointed out that the wars over history, empire, and colonialism that have flared up so viciously of late are about the future as much as the past. Philosopher Susan Neiman has written, “The history wars are not about heritage but about values. They are not arguments about who we were but who we want to be.” She is right.

What the traumatic events of late antique Byzantium remind us of is how exceptionally vicious the debate can be when people find themselves at a moment of intense historical anxiety, doubt, and fear. Early twenty-first-century Britain (and arguably the West) is one such place, an uncertain place, out of joint, lacking in a confidence that was once its apparent birthright. We enjoyed the fin de siècle triumph of Francis Fukuyama’s end of history. Indeed, that triumph was partly responsible for the abrupt collapse of the Soviet empire and the apparently unequivocal moral victory that followed it.

And then everything began to reel. Russia changed tack. China refused to liberalize politically. The entire Western capitalist system quaked under the weight of its own greed and mismanagement. A new, unforeseen, hostile force emerged and shed blood in New York, London, and other Western capitals. Mass immigration provoked anxious and sometimes aggressive nationalism. Liberalism began to eat itself in the groves of academic freedom. The climate noose slowly tightened. And a pandemic struck. The effect was shattering. Euphoria turned to disarray and soul-searching. How, and why, had this happened?

Not being a religious people, of course, we did not dream of ascribing any of this to the action or permission of God, or to such vague and antiquated ideas like sin, wickedness, offences, righteousness, or judgment. We have moved on from the eighth century.

But we still got rebuke homilies bringing to light our collective past and showing how wicked it had been. “Violence was not just the British Empire’s midwife,” Caroline Elkins tells her readers in the introduction of her book about the British Empire and violence. “It was endemic to the structures and systems of British rule . . . not just an occasional means to liberal imperialism’s end; it was a means and an end for as long as the British Empire remained alive.” Good governance, she insists, heading off any counter-argument, was merely a “fever dream.” The empire’s alleged “rule of law” in fact “codified difference, curtailed freedom, expropriated land and property, and ensured a steady stream of labor for the mines and plantations that fed Britain’s domestic economy.”

To be fair, many writers on the topic say that it is perfectly acceptable to be proud of empire. In his foreword to the collection of essays titled The Truth About Empire, which is effectively a three-hundred-page riposte to Biggar, Sanghera writes how “there is nothing . . . illegitimate about British historians wishing to justify and defend imperialism.” And yet you don’t have to read very far in most any modern book on the British Empire to come away with the clear impression that it was characterized almost entirely by prejudice, racism, violence, greed, exploitation, hypocrisy, and unreflective self-righteousness.

We also got a renewed pastoral providentialism. Modern rebuke homilies are clear that the sins of the nation are those of the nation and not simply of its rulers. Of course, much could be laid at the door of Robert Clive of India or General Reginald Dyer, but one of the repeating themes of modern histories of empire is how widespread the imperial sentiment was. The British people were imperialists, not just their leaders—and, in many ways they don’t even realize, they still are. These histories repeatedly reference (and display obvious shock at) the 2014 YouGov poll which reported that 59 percent of British adults “thought the empire was something to be proud of,” compared with 19 percent who were ashamed of it. This isn’t good enough. The people need to own their sin. “We badly need to understand . . . that for much of history we were an aggressively racist . . . force responsible for violence, injustice and war crimes,” says William Dalrymple. No Byzantine preacher put it better.

And we got a summons to repentance, which, if it is to be true repentance, needs to be serious, matched with action, a genuine striving for atonement. Leaders and institutions are summoned to say they are sorry, to apologize for the wickedness of the past. Christian ethicist Michael Banner has suggested “a national day of mourning.” Some institutions have pledged payment for their involvement in the slave trade. The “Brattle Report,” whose official title is Report on Reparations for Transatlantic Chattel Slavery in the America and Caribbean, estimates that the UK’s true debt is approximately $24 trillion, part of a bigger Western debt of somewhere between $77 trillion and $108 trillion. Repentance is necessary, and repentance must be serious.

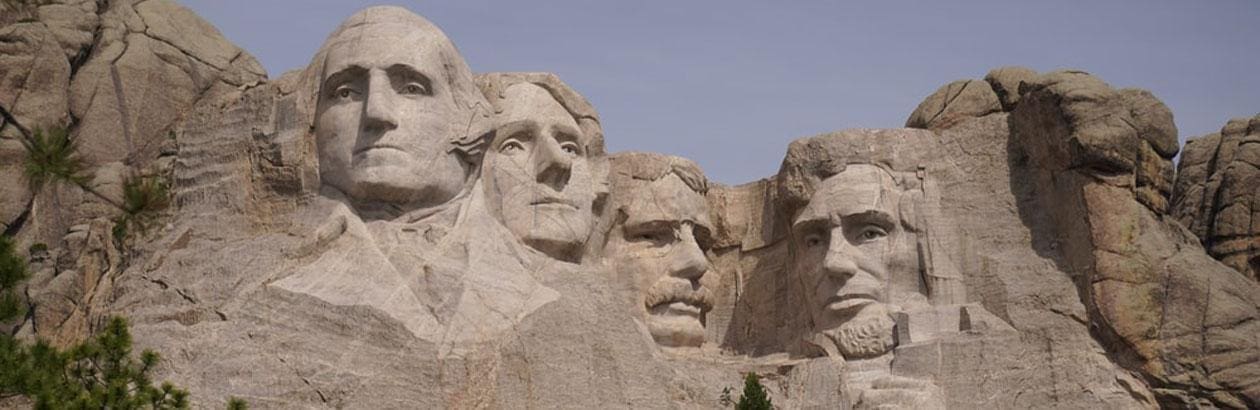

And of course we got our very own movement of iconoclasm. True penitents have taken to the streets. They have pulled down or defaced statues of the figures who were heretofore held as almost sacred but who are now perceived as icons of our sinful past. It is only by cleansing our present of our past that we can face the future.

Seeing Clearly amid the Fog of War

Despite what this might sound like, I am not passing judgment on these calls. There is a fair amount of suffocating self-righteousness and liberal self-loathing in these modern-day rebuke homilies, calls for national repentance, and demands for statue removal, but that doesn’t mean they are always wrong. Many a thundering Byzantine preacher might have been hypocritical or morally simplistic, but that didn’t necessarily render their homilies mistaken either.

Indeed, there is, equally, something a bit morally grotesque in the way the British have, at least until recently, celebrated the abolition of slavery but said comparatively little about the century-long period in which around three million African men and women were abducted and worked to death. Not without justification did the historian Eric Williams complain, in his 1944 book Capitalism and Slavery, that “British historians wrote almost as if Britain had introduced Negro slavery solely for the satisfaction of abolishing it.” It is thus hardly outrageous to call for a museum of colonialism, as Dalrymple has done, or to seek to pinpoint the amount that British families, institutions, and stately homes owed (and owe?) to descendants of those slaves. When people are culpable, repentance is necessary.

But we must also acknowledge what we are doing here. The empire wars are about the future direction of the country, and they have acquired their virulence because they are taking place at a moment of geopolitical uncertainty and anxiety, when history seems to be changing its tracks. Ultimately, people are disagreeing not about how good or bad our forebears were, but about how good or bad we are—indeed, about who we are and where we are going. No matter that the country is less religious now than it has been for a millennium. This is a religious argument, every bit as much as it was in eighth-century Byzantium, and there is no sign of its letting up soon.