T

He is a king, for I am no liar,

But in a battle he was maimed,

Wounded sorely, and so lamed

That naught is to be done at all.

. . .

A javelin pierced both his thighs,

And the pain doth him chastise,

Such that he cannot mount a horse,

Yet when he would have recourse

To sport or pleasure, in a boat

He is placed, and then, afloat,

Fish to his hook he doth bring;

Thus he’s called the Fisher King.

Chrétien de Troyes, Perceval

The sheer importance of a king’s physical fitness in medieval Europe is something that is difficult for us to understand, accustomed as we are to viewing the role of a head of state as political, rhetorical, inspirational, and even symbolic. But even in the late Middle Ages, a king was expected to lead his troops in battle, and to lead from the front if he could—like the unfortunate James IV of Scots, killed in battle at Flodden in 1513 leading a cavalry charge against the English. A nation saddled with an aged king, too old to ride into battle—or, worse still, a boy not yet ready to lead in person—was in serious trouble. And battle-readiness was not the only kind of physical fitness required of a king; he also had to be able to sire an heir. Physical injuries to the body of a king, therefore, especially those that prevented him fighting or rendered him impotent, were open wounds on the body of the realm itself. Indeed, the idea that a king must be physically unblemished and bodily intact is an ancient one; in the Byzantine Empire it was standard practice for usurpers to blind, castrate, or otherwise maim the outgoing emperor, who thereby became unfit to rule, and the last Merovingian king of the Franks was famously shorn of his long hair (which it was taboo to cut) before being consigned to a monastery; Pepin, the first of the succeeding Carolingians, was taking no chances.

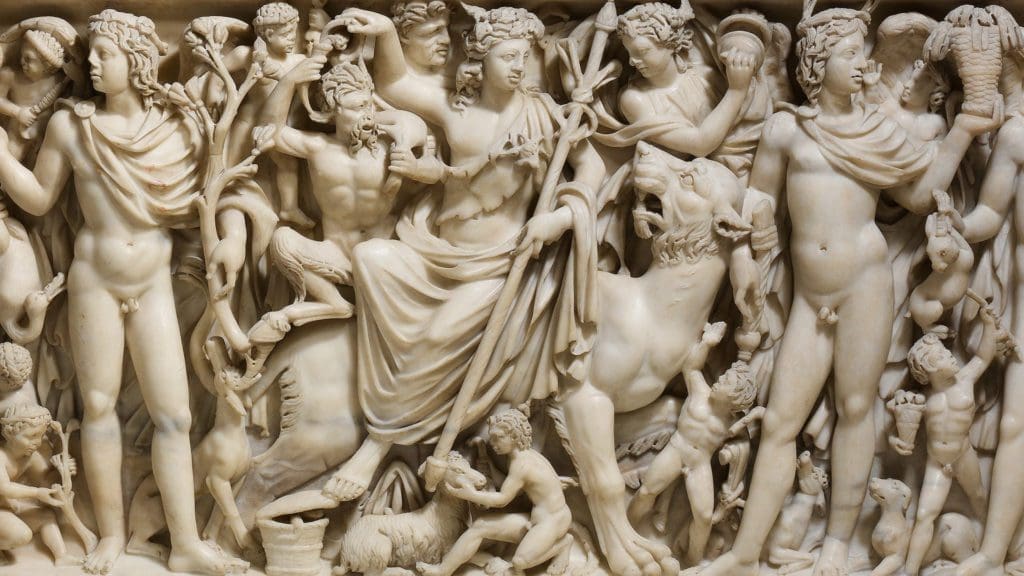

The archetype of the incapacitated king was one that haunted the imaginations of medieval people, because they knew and feared the chaos it could bring. It is an archetype whose most famous expression in fiction is the “Fisher King” of Chrétien de Troyes’s twelfth-century romance Perceval. The hero of the romance encounters a man fishing from a boat; the man turns out to be the unnamed king of a wasteland at whose heart is a splendid castle. It is during dinner at the castle that Perceval (and we, here at the very beginning of the romance tradition) first lays eyes on a magical golden cup—the Grail, whose guardian the Fisher King is.

But the Fisher King is a troubling guardian, a kind of half man, and certainly a half king: his legs having been injured in battle, he has to be carried about, and the only activity he can still do for himself is to fish from a boat. Perceval should have been the one to heal him; his healing, and the land’s, would have come about had Perceval asked him the right question. But, fearing to seem rude, he does not, keeping a disastrous silence.

Physical injuries to the body of a king, especially those that prevented him fighting or rendered him impotent, were open wounds on the body of the realm itself.

Later romances added a great deal more detail; the association between the Grail and Christ, names for the Fisher King, more details of his injury, and the idea that the healing of the Fisher King’s wound (although it never entirely heals) depends on the chivalric valour of the knights who serve him and the Grail. We also encounter the notion that the Fisher King’s injury was no accident, that he received it as a punishment for a sexual transgression of some kind.

Indeed, scholars generally accept that the injury to the Fisher King’s thighs is a euphemism for a groin injury causing impotence. This kind of castration was all too common when fighting or jousting on horseback, when an opponent might aim at a knight’s groin as a weak place where the plates of his armour inevitably joined. Historically, of course, royal infertility was blamed (usually) on queens rather than kings—and heirless kings like Charles II could often point to a brace of royal bastards to prove their virility. But there were cases where a king’s heirlessness and apparent unwillingness or inability to produce a male heir were sources of deep anxiety, even before the reign of Henry VIII. Edward the Confessor failed to sire any children, ostensibly because he took a vow of celibacy—and his heirlessness cost the English their kingdom. Henry I found himself heirless in 1120 when his son William Adelin drowned in the disaster of the White Ship, and he failed to produce another male heir with his second queen, Adeliza. The period after his death was known as “the Anarchy,” when, with no male heir, Henry I’s daughter Empress Matilda and his nephew Stephen of Blois struggled for supremacy. Examples like these may have been on the mind of Chrétien de Troyes when he made an impotent king the ruler of a wasteland. But why the Grail?

Romances like Perceval reflected the anxieties of their time; but they also became immensely popular works, reflecting back their fictional preoccupations onto reality. This was especially true in the late Middle Ages, when courtly culture clung to chivalric fantasies all the tighter because they were further than ever from the realities of political life. Richard II married, but apparently had no desire for children and saw himself in apocalyptic terms as a virginal perfect ruler. Perceval, and still more the second Grail knight, Galahad, were thought of as virgins; Richard would have been more at home in a romance than he was in fourteenth-century England. Sacred king or not, his cousin Henry Bolingbroke starved him to death in Pontefract Castle—Richard, like the Fisher King, had been defective in a fundamental way.

Likewise Henry VI, the hapless son of the great warrior king Henry V, seemed disinclined to marry or have children. Henry’s bouts of mental ill health became a national obsession, and in 1456 a commission of astrologers and alchemists was formed to look into a cure for the ailing monarch. An illness affecting the entire kingdom required a potentially magical as well as merely physical cure. The appearance of Halley’s Comet in the heavens in June made matters worse—in 1066, the comet had portended a change of dynasty, and Henry’s cousin, the virile Richard of York, stood ready to succeed Henry and the Lancastrians. In the event, when Henry did finally father a child, the ill-fated Edward of Westminster, it only made matters worse, exacerbating the anarchy that was the Wars of the Roses.

But perhaps England’s ultimate Fisher King was Henry VIII, blighted by his lack of a male heir and by what he believed to be the spiritual wound of marrying his brother’s wife. The comparison would not have been lost on Henry, a Tudor prince steeped in his Welsh ancestors’ Arthurian lore; and although he would undoubtedly have repudiated the similarities, Henry’s belief that a sexual transgression had cursed him, together with the unhealed jousting injury he received in 1536, and the wasteland he inflicted on so many of his subjects by dissolving the monasteries, assimilated him to the Fisher King in almost every way. In the twelfth century, during that same burst of Romantic creativity that gave us Chrétien’s Perceval, Robert de Boron had introduced the idea that the Grail was the cup of Christ, the chalice used at the Last Supper, and that Christ had given it to Joseph of Arimathea to bring to Britain. And so even Henry’s heightened obsession with his own sacrality, and claim to head the Church of England, made him a self-appointed guardian of the Grail of English Christianity: an older planting than that of St. Augustine of Canterbury’s in 597, and one that was, unlike St. Augustine’s, not given through any pope.

Like the glories of the Fisher King’s castle, the splendours of Henry’s court were at odds with the wasteland of “bare ruined choirs” that mocked his poorest subjects, deprived of the church’s charity. Like the Fisher King, Henry was condemned to spend his reign in restless searching—for a male heir, for a wife to bear him one, for the restoration of his health, and for religious truth.

But there is more to the Fisher King than just political allegory, and he is older than his twelfth-century chroniclers. He is a figure who looks back, deep into Celtic myth and legend, as well as forward to the martially or sexually defective kings of history who might be compared to him. In the old Welsh tale Culhwch and Olwen we hear that one of Arthur’s warriors, Teithi the Ancient, becomes sick and feeble because he was cursed never to have a haft remain on his knife. Like the Fisher King, Teithi is a king who allowed his kingdom to become waste—although, in Teithi’s case, he allowed it to be inundated by the sea. Kings who disregard their responsibilities, in the Celtic tradition, are punished with debility, or with an accidentally self-inflicted death suffused with bathos, like a ruler in Adomnán’s seventh-century Life of Columba who accidentally cuts himself with a knife, causing his death, after St. Columba prophesies that a companion of his journey would cause his death. The man cuts himself when startled by the noise of another man fighting nearby, while sitting in a boat—foreshadowing the centrality of a boat to the Fisher King’s story.

The sacrality of kingship, for whatever reason, is deeply bound up with the health of the king. Perhaps it is because, as Shakespeare well understood, the burden of kingship is itself a kind of debility.

The sense that the monarch’s or the heir’s health not only reflects the health of the nation but might be healed by magical means persisted. Queen Victoria’s reclusiveness, obesity and mobility problems in later life caused nineteenth-century journalists great anxiety, and as late as 1880, when Edward, Prince of Wales (the future Edward VII), lay ailing at Sandringham, two ladies of the court supposedly consulted with a local wisewoman in the Norfolk village of Flitcham and revived the heir to the throne with homemade mandrake wine. Twenty-two years later, the king’s poor health brought more anxiety—this time about whether he would be fit enough to undergo the prolonged rituals of the coronation. In the end, Edward VII’s coronation went ahead—but his grandson Edward VIII was never crowned, never anointed. This, combined with rumours of sexual dysfunction and an unhealthy relationship with Wallis Simpson, rendered the Duke of Windsor an unsatisfactory monarch (and even ex-monarch) in more ways than one. Queen Elizabeth II’s robust health and vitality, her many children, carried the country through the difficulties of decolonization; when King Charles III was diagnosed with cancer in 2024, the shadow of an ailing king portending an ailing nation once again hung over the country.

The sacrality of kingship, for whatever reason, is deeply bound up with the health of the king. Perhaps it is because, as Shakespeare well understood, the burden of kingship is itself a kind of debility. Lear becomes like a madman, Macbeth becomes the victim of his own destiny, Claudius is unable to prevent the breakdown of his family. And in the history plays, Shakespeare portrays a series of late medieval rulers who all, in one way or another, become victims of the heavy crown they wear. Even the martial glory of Henry V is tinged by the suspicion that a flame so bright can only burn for a short while. For the task of a medieval king was, in many ways, an impossible one. Frugal and prudent policies preserved a kingdom’s finances but potentially unmanned a king whose fate was to become a grey administrator, like the shrewd Henry VII. But the quest for martial glory was immensely expensive, as well as destabilizing to a kingdom destined to be ruled by regents in a king’s absence—as Richard I and Henry V found out. There were no easy solutions to the moral dilemmas of kingship, either—was Richard III right to supplant his nephew Edward V, given that a grown man had a better chance of leading the country in a time of instability and war? In most cases, a founding sin blighted the destiny of every dynasty—the Lancastrians’ murder of Richard II, the Yorkists’ murder of the saint-king Henry VI, the stain of illegitimacy on the Beauforts and Tudors.

Perhaps the Fisher King’s physical debility merely makes manifest the political, psychological, and moral debility of absolute power. There is a long cultural tradition of ascribing uncanniness to physical defects, from Shakespeare’s hunchbacked Richard III to Bond villains, which is liable to bring uneasiness in an era of disability rights.

But perhaps it is a mistake to read the legend of the Fisher King as a dehumanizing effort to stigmatize disability; after all, the Fisher King’s mysterious injury makes him a far more memorable character, and renders him dependent for his continued health on the feats of the knights of the Grail. The Fisher King’s very unworthiness, like St. Paul’s “thorn in the flesh” (2 Corinthians 12:7), makes more poignant the weight of his mission as guardian of the Grail.

In the end, the meaning of the Fisher King’s injury rises above an allegory for medieval political anxieties about the health of the body politic, or even the archetypal significance of its Celtic antecedents. For if the Grail guardian’s debility is the unhealed wound of sin, then we are all the Fisher King; we are all waiting for the coming of the knight who will ask us the right question.