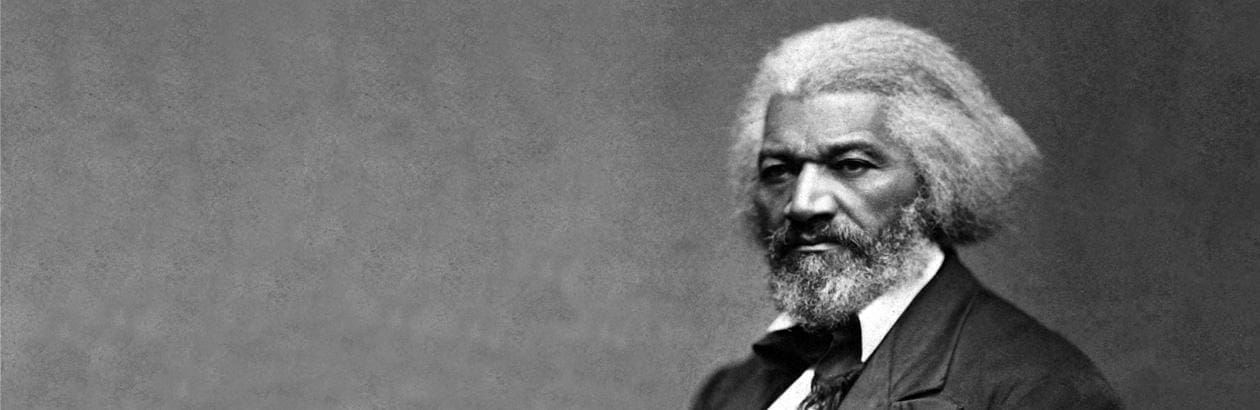

Douglass, this former slave, this Negro

beaten to his knees, exiled, visioning a world

where none is lonely, none hunted, alien,

this man, superb in love and logic, this man

shall be remembered . . . with the lives grown out of his life,

the lives fleshing his dream of the beautiful, needful thing.—Robert Hayden

Sometimes, the hinges of history swing as quietly as the turning of a page. The fate of a nation may turn on the clamour of battle, or it may turn on a thousand things more subtle, more hidden. In the story of the demise of American slave power, we all know the names of Gettysburg, Shiloh, and Bull Run, but just as important as these events was a day in 1825 when a little black boy in Baltimore learned his letters.

In learning to read, Frederick Douglass embarked on a path that would lead to his becoming the most powerful advocate of his time for black dignity. He became an icon, the most well-known face of the age, all through the force of his power as a writer and a speaker. His arguments reshaped the conscience of the country.

Language, for Douglass, had an intimate relationship with flesh—that is, with practical, lived reality. His language had the power to make people feel in their own flesh the suffering bodies of slaves; it had the capacity to motivate them to relieve that suffering.

Both the logic of his arguments and their inspiration lay in the Word made flesh. His key notion—that all men and women are children of one Father, and therefore possessed of immeasurable dignity—came from his reading of Scripture. The story of the suffering Christ, put to death unjustly by the reigning social hierarchy, was a subversion of the corrupt power dynamics of human societies, and showed that God identifies with the oppressed, marginalized, and unjustly persecuted.

Douglass saw himself as “fleshing the dream” of the one who came to “proclaim liberty to the enslaved and set the captives free.” For the Word to become flesh and dwell among us means, at least in part, for our society to be organized in accord with the truth of universal, unrestricted human dignity—it is to become a civilization of love. The ever-widening and deepening effort of Douglass to speak that word of love still reverberates in our world, and instructs us in the way to speak the Word into flesh in our own time.

The Bread of Knowledge

Sophia Auld, the mistress of the house in which the young Douglass was enslaved in Baltimore, was, in certain respects, a kindly woman, and it was she who gave the boy his first lessons in reading. Something in her husband, however, instinctively rebelled against the notion that a slave should read. Master Hugh absolutely forbade it, and Sophia soon adopted his attitude.

In a remarkable bit of psychological analysis that appeared in his first autobiography, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, written in his twenties, Douglass described the way in which slavery degrades the mind of master and slave alike. Sophia, who was natively kind and gentle, had been tutored by slavery to become a terror.

She had bread for the hungry, clothes for the naked, and comfort for every mourner that came within her reach. Slavery soon proved its ability to divest her of these heavenly qualities. Under its influence, the tender heart became stone, and the lamblike disposition gave way to one of tiger-like fierceness. . . . Nothing seemed to make her more angry than to see me with a newspaper.

When Sophia made this about-face, however, the boy found new teachers of his own. He met the neighbourhood’s young, poor Irish lads in the alley and asked them to teach him to read new words. He would bring bread for their bellies, and they would give him the “bread of knowledge.” It was through poor children, whose naïve attachment to truth had not yet been papered over by Baltimore’s corrupt social hierarchies, that Douglass learned to read. They often consoled him that somehow, someday he would get free.

It was not enough, of course, that he merely read, but that he read things that were true. These things made a home in the hidden parts of his soul, and, watered by his own native genius, sprouted into action.

But the written word became a trouble to him, because it revealed the injustice of his own position. Even as his expanding knowledge lit the fire of freedom beneath him, it made the hot manacles of slavery chafe all the more. He received the language of liberty and emancipation first through a set of speeches he had found by Richard Sheridan, an Irishman, on the issue of Catholic emancipation. Suddenly Douglass had a vocabulary for his own plight, and he could recognize the injustice in a new way by the dark contrast it presented to the brilliant light of liberty and dignity that is proper to the human person.

It was not enough, of course, that he merely read, but that he read things that were true. These things made a home in the hidden parts of his soul, and, watered by his own native genius, sprouted into action. He was able now to understand the word of Scripture, and it provided for him the foundation for every major argument of his life. Above all, it gave him the conviction that God identified first and foremost with the suffering, with the oppressed, with the downtrodden—to the point that the Almighty himself had become one of them. This truth helped to liberate him inwardly from mental bondage, and he soon began to teach the Bible to his fellow slaves. In time, it would become the ingredient out of which he made the argument for the downfall of slavery.

Thus, through the use of the gospel to call a society away from wickedness, the word became the liberating word made flesh. It would continue to take on flesh as the nation headed toward the hoped-for, but hardly imagined, demise of slave society. The incarnation began at Bethlehem, but it continued through history in the hearts and limbs of people like Douglass.

The Slave as Scapegoat

René Girard, the famed French sociologist, described the power of the gospel story much like Douglass did. His socio-historical framework illuminates the work that Douglass undertook. For Girard, the gospel was a subversion of the ritual violence on which almost all human society was built. It was not a story of mere historical interest, told once and then over and done with, but one whose influence could be traced throughout history as revealing the lies that oppressors tell.

Human societies, Girard thought, necessarily establish hierarchical orders. This is because the nature of human desire is imitative (“mimetic” is his fancy word): we shape our own desires based on what we see other people pursuing. If everyone is on an equal footing, desiring the same scarce goods as her neighbour, rivalries will inevitably spring up, and after that, competition, and with competition, violence. Once the violence begins, it initiates a cycle of escalating retribution, where the members of the community turn on one another in confusion and defensive aggression. Hierarchy is a way of preventing this disorder by establishing the rights and status of some members of the community as naturally superior to those of others.

In the midst of this chaos, where each is turned against the other, the parties must agree on someone to blame, or else they will tear each other apart. By an unconscious process, the community will tend to fix on a member (or a group) with a “scandalous difference” that sets them apart from the community at large. Perhaps it is a person with a disability, perhaps a foreigner, perhaps an unmarried, pregnant woman. Once this person is chosen as the “real” cause of the disorder, all kinds of crimes are attributed to her, and, in order to free and heal the community, she is murdered. The community is cleansed, and the hierarchy may reestablish itself. When people know their place, they will not compete for the same goods. This, in Girard’s view, occurs constantly in history, whether in the massacre of Jews during the Black Plague or the ritual sacrifices of the Maya.

Girard notes that even the gospel, which seems so clearly to take the side of the oppressed, has been twisted into a force for domination. American slavers themselves did this; Edward Covey, the cruel slave-breaker who haunted Douglass’s adolescence, was a devout man on Sunday, but a torturer during the week. He seemed to believe that this master-slave relationship was one intended by God. But this was an abuse of the clear message of the cross, and the likes of Douglass would show this to be so: “Your prayers and hymns, your sermons and thanksgivings, with all your religious parade and solemnity, are,” he wrote, “to Him, mere bombast, fraud, deception, impiety, and hypocrisy—a thin veil to cover up crimes which would disgrace a nation of savages.”

The story of the gospel, Girard wrote, was in fact the unique and revolutionary instance in which the scapegoat was revealed to be innocent and the community at large to be wicked. It unmasked the myths that justified all kinds of violence as selfish falsehoods. The power of this revelation of God as the suffering scapegoat and not on the side of the wider community did not end with Christ’s death and resurrection; rather, it was a real presence acting in human history, uncovering the lies that communities tell themselves in order to oppress their neighbours.

It would be a century before Girard would make his analysis of ritual violence, but Douglass had read the gospel well and detected the themes that Girard would later explicate. In his speech against lynching, he anticipated Girard, identifying the root of racial violence in the fear of a threat to the present class hierarchy:

The Jew is hated in Russia, because he is thrifty. The Chinaman is hated in California, because he is industrious and successful. The Negro meets no resistance when on a downward course. It is only when he rises in wealth, intelligence, and manly character that he brings upon himself the heavy hand of persecution.

When a black man transgressed the boundaries of the existing hierarchy, he became a scandal to be eliminated: “When the Negro is degraded and ignorant he conforms to a popular standard of what a Negro should be. When he shakes off his rags and wretchedness and presumes to be a man, and a man among men, he . . . becomes an offense to his surroundings.”

The only solution, Douglass thought, was the gospel solution—that is, the embrace of the “sacredness of human life.” This required an acknowledgement of universal, common humanity.

Upon the slaves, Douglass noted, slavers poured all of the guilt that was actually their own. Slavers, and later, lynch mobs, would routinely accuse black men of rape, but, Douglass wrote, “for two hundred years or more, white men have in the South committed this offence against black women, and the fact has excited little attention, even at the North.” For centuries slave masters had systematically robbed slaves of the fruits of their toil and had been unremittingly violent to them, and yet, by a twisted irony, slave society stereotyped the slave and not the master as thieving, lustful, and aggressive. Still more violence, then, was the means by which the slave society had made a lasting peace with the deceptions that lay at its heart.

The only solution, Douglass thought, was the gospel solution—that is, the embrace of the “sacredness of human life.” This required an acknowledgement of universal, common humanity:

I utterly deny, that we are originally, or naturally, or practically, or in any way, or in any important sense, inferior to anybody on this globe. This charge of inferiority is an old dodge. It has been made available for oppression on many occasions. It is only about six centuries since the blue-eyed and fair-haired Anglo-Saxons were considered inferior by the haughty Normans, who once trampled upon them.

The truth that Douglass told, about the injustice and falsity of slavery, about the dignity of all people, about the true fraternity of the human family, became the prick of conscience in the psyche of the North.

The Trade Winds of the Almighty

Over the course of the first several years of the Civil War, a dramatic shift took place in the consciousness of the country and in the consciences of its leaders. At its beginning, very few people in positions of influence were willing to consider immediate abolition; only a handful of radical Republicans openly endorsed it. Men like Abraham Lincoln and Ulysses S. Grant, who had always had a personal opposition to slavery, saw saving the Union as the real priority and remained hands-off on the slavery question. Yet in time, slavery would reveal itself to be the real cause and matter of the conflict, and Frederick Douglass had given the North a language for this newfound conviction—if they had ears to hear it.

Over the course of the war, Douglass’s rhetoric took a decidedly Old Testament turn. He prophesied, “The land is now to weep and howl amid ten thousand desolations. . . . Repent, Break Every Yoke, let the Oppressed Go Free for Herein alone is deliverance and safety!” His rhetoric consistently emphasized the war’s divine meaning.

When the Emancipation Proclamation went out, Douglass detected a change in the nation’s destiny. The ship of state would now “swing round, her towering sails . . . swelled by the trade winds of the Almighty.” This proclamation, he said, was the work of God, even if it was the reluctant product of military necessity. “You have wronged us long and wronged us greatly,” Douglass addressed white listeners, “but it is not too late to retrieve the past.” In spite of human intentions, this awful war was being transmuted by God into a work of repentance and redemption. As Joseph says to his brothers in Genesis, “What you intended as evil for me, God meant for good.” This war, in Douglass’s words, had become a “school of affliction” that would show the “necessity of a new order of social and political relations among the whole people.”

As Douglass preached this message, Lincoln’s mind turned toward the eternal too. His language was increasingly filled with an awestruck sense of the magnitude of the divine plan at work. In the tragic crucible of the war, he grew to see the events as a matter not of political expedience but of providential justice, and it was in this frame of mind that he penned his “Meditation on the Divine Will.” It’s possible that Douglass himself had influenced Lincoln in this change, though we have no precise record of the ways in which Douglass’s writing and speaking affected the president in this respect. We know he followed Douglass’s work with admiration, and we know they met and talked warmly on several occasions, but we do not know the full extent of their conversations or mutual influence.

Even as Douglass remained disappointed by Lincoln’s hedging over slavery at the beginning of the war, he was overjoyed at the powerful and prophetic poetry of the Second Inaugural Address. It echoed nothing so much as Douglass’s own message, and was perhaps the finest speech given by an American president:

The Almighty has His own purposes. . . . Fondly do we hope—fervently do we pray—that this mighty scourge of war may speedily pass away. Yet, if God wills that it continue, until all the wealth piled by the bond-man’s two hundred and fifty years of unrequited toil shall be sunk, and until every drop of blood drawn with the lash, shall be paid by another drawn with the sword, as was said three thousand years ago, so still it must be said “the judgments of the Lord, are true and righteous altogether.”

To be sure, many, if not most, in the North remained beholden to habitual prejudice, but the influence of Douglass and of the war was real. At the beginning of the war, Lincoln was a gradualist and Grant was ambivalent. As the conflict trended toward its end, both had become firm in the conviction that slavery must end forever, and end now.

At the proper moment in history, there had risen up a Douglass, a man with a sense of divine justice, moving torturously, imperfectly, toward the truth of things. Douglass—and eventually Lincoln alongside him—perceived himself to be an actor in a divine drama, overturning a wicked system. None of the men and women who effected the liberation of the slaves were perfect, none free from error or meanness, but many saw themselves as acting a part in a providential plan to make right what humankind had made wrong. Can we argue with them?

This Man, Superb in Love and Logic

Today, of course, we are aware that the moral grandeur of abolition was not followed by anything rosy or idyllic. Prejudice continued to reign in North and South alike; black Americans remained a scandal to an old form of white hierarchy, and they were met with ongoing violence and prejudice. We are aware that such things continue to this day.

Douglass himself was painfully alert to this fact, but the healing message of the gospel continued to work in his heart and to work out of his mouth. In public, he crusaded against the continuing injustice toward his fellow black Americans. In private, he was ridding himself of the burden of hatred and vengeance.

Prior to and during the Civil War, Douglass, hot with righteous anger, called for the blood of slave owners, urged men on to battle to crush the unrighteous. He praised and admired the murderous campaigns of John Brown, whose cause was just even when his means were not; though he could never bring himself to join in them.

But hatred, too, can be a kind of bondage. We can feel the weight of it as we walk; we chafe under the fetters that bind us to it. If we are not free of it, it can wear away all that is tender and leave behind only exposed and painful wounds. Justified as Douglass was in anger, hatred was something different, and he wanted to rid himself of it.

In old age, Douglass would come to desire reconciliation with those who had been his “masters.” Anger and bitterness had become their own trial, and he hoped now for healing. He was with his first master, Thomas Auld, Sophia’s brother-in-law, on his sickbed as he neared death. The two men held hands. Thomas wept, and shook, and wept. Douglass’s voice caught in his throat and he stood, for once, speechless. Of course, Auld did not deserve Douglass’s forgiveness, but deserving is not the point of forgiveness. The message of the gospel had penetrated so deeply into Douglass’s heart that he now sought to see the image of God even in the sinful, broken, and wicked. Douglass told the dying old man that he considered them both to be victims of an evil system. Auld agreed to its evil with remorse. They parted on terms of affection.

Frederick Douglass had been all these many years making the Word effectual in the flesh of history. The Word that revealed the dignity of every human person was his word for breaking the chains of slavery. That Word, which Douglass saw as replacing ego and greed with love and righteousness, had enveloped him to the point where he could act in accord with those chilling words uttered from under the rough and bloody beam of the cross: “Forgive them, Father, for they know not what they do.” What he had received and what he had preached was nothing other than the impossible, essential, and childishly simple commandment: love thy neighbour.