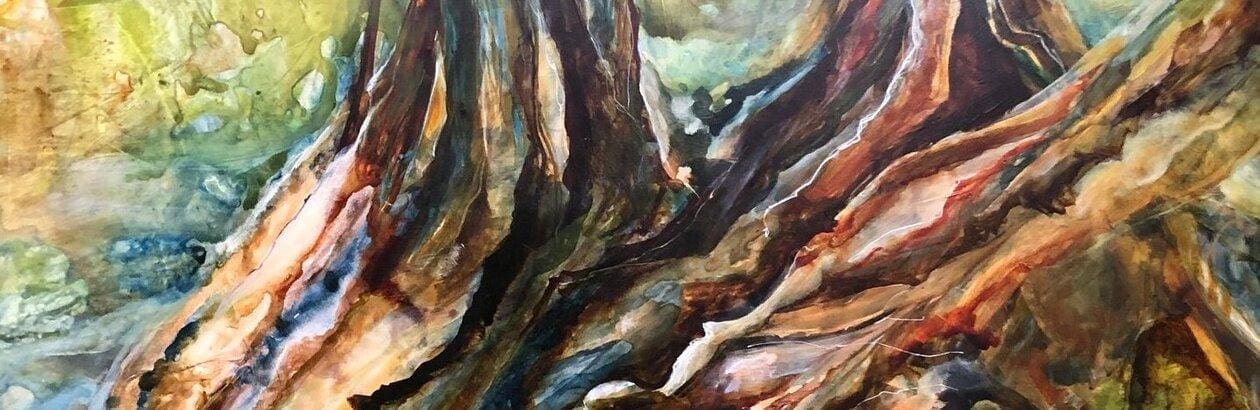

Last winter, deep into reading an article about trees in the New York Times, I found myself wondering, unexpectedly, about the connections between storytelling, social structure, and human agency. The author had made a passing remark: “Humans are not the only species that inherits the infrastructure of past communities.” It struck me that we, like trees, depend on stories of the past that stretch down into layer upon layer of soil. We are constrained by these deep stories, frustrated by our inability to define ourselves apart from them just as trees cannot literally uproot themselves from a forest. Yet they are the making of us, whether we are aware of them or not. These stories structure our lives, shape the ways we bend and grow, relate to one another, and regard our neighbours.

We are not, however, passive recipients of the stories we inherit. We are narrators, even as we are participants. We are agents, imbued with the dignity of imagination. Perhaps this is why I continually turn to literature and the great storytellers to decipher not only the ways that the past constrains our lives but also how we can break free. Indeed, the best characters are those who change, who find some thread of redemption that causes a shift, however subtle, from the status quo. Structures—the deeply rooted legacies conditioning how we live and breathe, love and move—will never disappear entirely. But, in spite of what we often witness in our day-to-day lives, they are not immovable. Persons who do the still, small work of daring to imagine change, who retool possibility out of the “infrastructure of past communities”—these are the most gifted narrators among us.

This list is one attempt to capture some of the great narrators of our age, those engaged in the courageous act of allowing new stories to emerge from the old.

Apeirogon

by Colum McCann

Leave aside this book’s meticulous literary construction. It is also a remarkable achievement as a sustained meditation on the intertwined griefs of personal and political trauma. Apeirogon—the mathematical term for a geometric shape with an infinite number of sides—defies genre as a novel, partly because of its composition and partly because of its subject matter: the conflict between Israel and Palestine. Inspired by One Thousand and One Arabian Nights, McCann narrates the story as one thousand and one distinct but interrelated vignettes. The choice to bob and weave between subjects as wide-ranging as François Mitterand’s last meal before his death, the physics behind the strike of David’s slingshot to Goliath’s head, or the contents of Yasser Arafat’s welcome basket when he arrived in Washington, DC, in 1993 may appear frivolous, even indulgent at first blush. But as the book progresses, it becomes clear that through every sidebar and tangent, McCann traces the invisible lines of an unbendable structure holding the Palestinians and Israelis in a deadly vise grip.

We, like trees, depend on stories of the past that stretch down into layer upon layer of soil.

What overlays each of these one thousand and one parts is an unlikely friendship forged through the bonds of suffering. Two everyday men, one Israeli and one Palestinian, have both lost their preteen daughters to the violence. We learn the excruciating details of both girls’ deaths, but we also learn the mundane details of the two fathers’ clawing struggle out of despair. We learn how they flick their cigarettes at the end of a long day and the direction in which they swerve their motorcycles on desert backroads. We learn about their guilt, ambivalence, academic achievements, families, and finances.

But mostly, we learn the stories they tell over and over and over again, to anyone who will listen, about their daughters. We learn that they travel together all over the world to tell these stories together, stubbornly refusing to believe that the violence that took their daughters should take still more fathers’ daughters. And by the end of the book, we learn that out of the one thousand and one stories McCann tells, this one story, of two fathers from opposite sides of a conflict who love their daughters and come to love each other through shared loss, is the story on which the thousand others depend.

Beloved

by Toni Morrison

In Beloved, Toni Morrison dares to tell a story of slavery, yes, but one that asks what happens after escape, emancipation, and so-called freedom. She opens the book with a quote from Romans: “I will call them my people, which were not my people; and her beloved, which was not beloved.” There, her narrative begins with what slavery denied at every turn and emancipation did not guarantee—belonging. In the foreword, Morrison sheds light on her motivation for writing this story and entering the “repellant landscape” of slavery, a territory that was “hidden, but not completely; deliberately buried, but not forgotten.” She contemplates “the different history of black women in this country—a history in which marriage was discouraged, impossible, or illegal; in which birthing children was required, but ‘having’ them, being responsible for them—being, in other words, their parent—was as out of the question as freedom. Assertions of parenthood under conditions peculiar to the logic of institutional enslavement were criminal.”

We are not passive recipients of the stories we inherit.

True to her purpose in unearthing this legacy, Morrison introduces us to Sethe, formerly enslaved and haunted by the ghost of her baby daughter. Sethe declares, “I got a tree on my back and a haint in my house.” A stubborn remnant of the whip’s lash, leaves and knotted branches made of dead skin stretch from the nape of her neck to the top of her buttocks. Like so many of Morrison’s characters, Sethe chafes against the constraints on her body and mind. She is stifled by stigma but imagines herself as wanted. She is wounded but wants healing. Here, writing uncompromisingly from the particularity of the African American experience, Morrison invites us to sit and listen to the painful and vital stories of people whose desire for freedom is made manifest by ghosts and scars. Beloved is a story well worth listening to again and again.

The Plague of Doves

by Louise Erdrich

Louise Erdrich’s entire body of work speaks to the subject of how we reckon with history, think generationally, and find a path toward humanizing the other. In 2016, Erdrich wrote about the Dakota Access Pipeline protests for the New Yorker. True to form, she wrestles in this essay with the possibility of forgiving the sins of the past, wondering how realistic it is to proclaim any sort of absolution for the US government’s centuries of abuse. But, at the end of the piece, she finds some resolution for her skepticism, marvelling at the compassion of indigenous youth, teenage “water protectors” who practiced kindness toward police officers standing on the opposite side of the barricade by offering them water and even a prayer.

This interplay between the crush of history and the hopeful breaking in of the future characterizes much of Erdrich’s fiction. She sets many of her novels in what I might call convergent time, where past, present, and future overlap. The opening sequence of Plague, which recounts a Catholic community made up of Native Americans and white immigrants in North Dakota praying away a plague of doves descending on their crops, derives from a real-life incident Erdrich came across in a newspaper clipping. The other real-life incident that inspired the story also took place in North Dakota. In 1897, three Native Americans, one a thirteen-year-old boy, were unjustly hung as punishment for the death of a family of farmers.

The story contemplates what happens not only to the people who lived through these two events but also to the generations after—the children and the grandchildren. Through intergenerational flashbacks and shared memories, Erdrich explores the collective guilt alive in the community many decades after the lynching. As she does in all of her other novels, she probes the often messy links between families and communities, the ways that the forgotten history is the most important history, and the unending possibility for mercy in any circumstance.

The Final Solution

by Michael Chabon

This tiny book with a title bearing the weight of the world’s evil is about a boy and his bird. The Jewish boy at the centre of the story—mute, age nine or ten—has lost his entire family to the Holocaust and found asylum with a vicar’s family in the English countryside. He is utterly alone, except for a single companion, an African grey parrot. But when the bird disappears suddenly, a new figure enters the boy’s life. This old man, hunched and frustrated with the encumbering inevitabilities of age, nonetheless maintains a reputation for eccentricity, a searingly quick mind, and powers of detection. He is never named, but Chabon makes us understand that he is an elderly Sherlock Holmes.

When the boy first discovers his avian friend has vanished, he looks for him on his own, climbing the roof of the vicar’s home. Holmes observes this scene, watching the boy finally agree to come down and land precariously in the arms of a neighbour who holds him as he wails from a broken heart, the first true noise he has made since he arrived. Holmes witnesses the boy’s pain, the grief upon grief that he cannot speak, and he resolves—age be damned—that he will restore the bird to his boy. What once would have been a small task for a brilliant detective becomes monumental for a man whose faculties are less intact, but Holmes’s last act as a detective will prove one of tikkun olam, a small act of repair for a boy whose world has shattered entirely.

Sing, Unburied, Sing

by Jesmyn Ward

Grief has marked Jesmyn Ward’s life repeatedly, visiting her through the ravages of Hurricane Katrina, as well as the sudden losses of her brother and, recently, her husband. And so grief has also become an abiding theme in her stories, which are set in a fictional town on the Mississippi Gulf Coast, where members of her family have resided for generations and where Ward now lives. In the Faulknerian tradition, Ward uses characters who live in our own times to explore themes that spring from the soil of the Southern United States. Yet that necessitates mining deep, generational pain often hidden from the immediate consciousness of her characters but ever-present in their choices, the constraints on their lives, and their relationships.

Morrison invites us to sit and listen to the painful and vital stories of people whose desire for freedom is made manifest by ghosts and scars.

Sing, Unburied, Sing, which won the National Book Award in 2017, is no exception. In this novel, through the eyes of children—one alive and one long dead—we experience the effects of the criminal justice system on three generations of one family. A trip to and from the Mississippi State Penitentiary exposes family secrets, and Jojo, our thirteen-year-old protagonist, must grapple with who he will become in light of these revelations.

Ward is particularly gifted at creating singular voices for her characters, and in the opening paragraph we meet Jojo as he prepares to help his grandfather slaughter a goat. He says, “I try to look like this is normal and boring so Pop will think I’ve earned these thirteen years, so Pop will know I’m ready to pull what needs to be pulled, separate innards from muscle, organs from cavities. I want Pop to know I can get bloody. Today’s my birthday.” On the journey that ensues, in learning to listen to his family, to himself, even to the departed souls that haunt his world, Jojo does indeed earn his thirteen years.

What You Have Heard Is True: A Memoir of Witness and Resistance

by Carolyn Forché

Carolyn Forché’s memoir about her time in El Salvador during the years leading up to the country’s civil war, which lasted from 1980 to 1992, pulses with the dire refrains of Leonel, the stranger who appears on her doorstep armed with butcher paper to diagram a map of his country on her kitchen table. He is there to convince her that she must see and know what he sees and knows: that the Salvadoran people stand on the verge of the abyss. He is not wrong. The war about to ensue will cost his people nearly one hundred thousand lives—many of them disappeared, many of them brutally tortured, many of them poor and young.

Leonel knows almost nothing about Forché, except that she is a poet, but he remains confident she will attach herself to his desperate mission. He comes with a litany of facts: El Salvador “is the most densely populated country in the isthmus and among the poorest in the hemisphere.” He tells her that “one in five children die before the age of five, and eighty percent of people have no running water, electricity, or sanitation.” He speaks of men and women who “make their living harvesting coffee and cotton and cutting cane, moving from harvest to harvest,” and who rarely, if ever, see more than a dollar a day for their labour.

Holmes’s last act as a detective will prove one of tikkun olam, a small act of repair for a boy whose world has shattered entirely.

They begin at her kitchen table, then traverse frantically from one end of El Salvador to another. Leonel repeatedly tells Forché to “connect the dots.” He says, “Look at this. Remember this. Try to see.” This book testifies to her fidelity to his request. Indeed, Forché sees and remembers the indescribable: mutilated bodies, abduction conducted in the light of day, the delusional rantings of a sociopathic military official. But she also witnesses the immovability of the campesinos, the protections afforded among friends, and Monseñor Óscar Romero at work, blessing the bodies laid before the altar where he preaches. There, he reads the names of the dead—every last one of them—over the radio waves each week, until he must join these departed souls.

And, just when it seems there is no more to see and remember, decades later, Forché welcomes another stranger from El Salvador into her home. Like her, he has a mandate to remember what he has seen. Taken in by the military and brainwashed, he operated as a henchman during the war, and he has come to the United States to testify to the terrible crimes he and his superiors committed. That is, if anyone cares to listen. When he grows discouraged at the prospect of American officials taking him seriously, he remarks, “People think that what happens to someone else has nothing to do with them. They think that what happens in one place doesn’t matter anyplace else.” Ultimately this man leaves, having never found an audience, and, as someone who committed crimes against humanity, without any prospect of safe haven. His is yet another life consumed by unnecessary violence. Yet, in writing this account, Forché brings forth his unheard testimonies along with many others, so that we also may see and remember.

The Underground Railroad

by Colson Whitehead

Colson Whitehead’s novel The Underground Railroad is a stomach-churning, honest account of the machinery of slavery—and, shockingly, the machinery of freedom. For, yes, liberation is also a machine in this novel. It is a train, and it is a system of relations, and it is so harrowing that survival becomes a relative term. Here, Whitehead brilliantly complicates the way we tell the story of how people escaped slavery. Harriet Tubman goes unmentioned. Instead, we follow our protagonist, Cora, who travels from state to state with a brutal slave-catcher hot on her heels.

Moses agonizes over the question all humans face: Who am I?

At each destination, Whitehead renders the realities of racism and its violence slightly differently. By treating Georgia, South Carolina, North Carolina, and Indiana as different worlds run according to slightly different logics, he uses distinct settings to tease out different aspects of the systems of oppression Cora endeavours to escape. But he never veers too far from historical grounding to allow us to miss that the structure he describes is our own, the one we inherited and perpetuate in our own time and conditions. In one passage, a character casually notes, “The ruthless engine of cotton required its fuel of African bodies. Crisscrossing the ocean, ships brought bodies to work the land and to breed more bodies. The pistons of this engine moved without relent. More slaves led to more cotton, which led to more money to buy more land to farm more cotton.”

While Whitehead’s work focuses on the inescapable complicity of nearly every aspect of society in the system of slavery, the sense of movement that throbs through the novel undermines the temptation to hopelessness. By movement, I mean the literal, clandestine, willed-into-existence flow of people toward liberation. Cora never stops, never rests, moving from one place to another by any means possible, determined never to settle until she arrives in a place where she will flourish. Through Cora, Whitehead has given us a picture of hope in motion.

Moses: A Human Life

by Avivah Gottlieb Zornberg

Unlike the other books on this list, this book is not a work of fiction or memoir, but it does treat the story of Moses’s life as literature, a story to be taken seriously. In Western culture, Moses is perhaps regarded as the ultimate Great Man. Rescued by a trio of women and raised as a prince of Egypt, Moses redeems his people, leading the Israelites to the Promised Land. He is exceptional in every respect, triumphant over forces of evil and oppression. Yet, in this book, Avivah Zornberg, Torah scholar and author of numerous books on Genesis, Exodus, and Numbers, returns Moses to the source text and its commentary, refusing temptations to portray him as a Great Man by embedding him once again in a particular time and place, as a human who is not so exceptional, who is mired in an identity crisis, and who lives out of crippling fear.

Zornberg places Moses’s life in dialogue with philosophy, psychology, and political science, but she also draws from the deep tradition of Jewish midrash, employing the Talmud and other ancient rabbinic interpretive texts. In doing so, she allows us to see him anew, recontextualized in the Jewish storytelling tradition. “Beginning in the experience of muteness and solitude,” she says, “Moses moves toward a difficult and singular encounter with the singularities of his people.” Here, Moses agonizes over the question all humans face: Who am I?

Fundamentally, Zornberg tracks Moses’s emergence from death to life. In her telling, Moses at the burning bush remains “submerged”: “He lives within closed spaces, hidden in his mother’s house; in the box, in the river; in the palace; burying the dead Egyptian in the sand; hearing God calling from within the Bush, hiding his hand within his bosom. God urges him to ‘bring forth’ what is incubating within him: to utter, to redeem, to expose to the light. . . . Everything is at risk, to the limit of life itself.”

Reading Moses as dependent, weak, unable to speak, yet “becoming,” Zornberg defines human agency as dynamic, emergent, and relational, particularly with the divine. She argues, “The hazard of idolatry is the wish to have an object perfectly adjusted to our needs. . . . If God is kept in mind, however, the desire, precisely, for an achieved perfection must be frustrated. In this way, we remain—always incomplete, within and without—hot in pursuit of the infinite.” Told as a story of relentless surrender, Moses’s life becomes a model for our own lives, for what it might look like to live from an identity and personhood that is always in formation, shape-shifting alongside the structures that constitute our lives.