P

“People never really believe they were taken from their mother’s womb and laid on her breast,” the title character muses in Marilynne Robinson’s novel Lila. As a mother of two, Robinson likely knows that incredulity can linger on both sides of the equation, perhaps for a lifetime. I have a clear image of the moment my daughter was first handed to me, but whenever I call it to mind, it’s impossible to separate the visual memory from a visceral sense of amazement that such a moment happened at all. In her fascinating new book, Natality, Jennifer Banks—herself a mother of three and a senior executive editor at Yale University Press—lets her own sense of maternal astonishment lead her where wonder has led thinkers for millennia, to philosophy. The wisdom she uncovers has much to do with birth, as the book’s subtitle promises, and even more with what the irreducibly strange miracle of our entrance into the world tells us about the gift we have been given, not only of life but of free will.

Early on in Natality, Banks offers a moving recollection of the disorientation she felt upon returning to work following the birth of her first child in 2009. After dropping “my daughter off at a small, cramped daycare” and “passing her into the arms of another woman,” Banks writes, and with the child’s cries still echoing in her ears,

In this clash between expectations and reality, between “the outer world of meetings, conferences, opinions, and ideas” and the inner world of feedings, diaper changes, and other humble acts of care, between what is written about and spoken of and what isn’t, Banks finds grist for the mill. A single word in a scholarly book proposal—“natality,” coined by the philosopher Hannah Arendt, who remained childless—sets her off on a decade-long search for intelligent writing about birth and about what it means that we are each, even in an age of IVF and surrogacy, of woman born.

The seven thinkers Banks has compiled into what she calls “a string of natal pearls, poetically arranged,” are not equally illuminating. But even the more flawed figures—and I’m pointing squarely at Friedrich Nietzsche here—are useful in delineating where Arendt’s understanding of natality overlaps with Banks’s and with mine. Other readers might divide up the territory differently.

Five of the seven were mothers themselves, and the book’s examination of birth in its most straightforward sense—that is, as a discrete physical event—makes for sobering reading. One does not come away envying eighteenth-century women, nor their children. The chapters on Mary Wollstonecraft (1759–1797) and the daughter whom she died delivering—a daughter who would grow up to become Mary Shelley (1797–1851), author of Frankenstein—are filled with excruciating details. Alongside Wollstonecraft in Paris during the French Revolution, we see infants handed over to impoverished wetnurses and left to hang for hours in harnesses from the rafters in overcrowded cottages, “with rags stuffed in their mouths to mute their wailing.” Fully half of such children died.

Wollstonecraft was well acquainted with these and other horrors, having seen firsthand how the laws and norms of that era of revolutions, both industrial and political, could be used to prioritize male lust and male greed over the well-being of women and children. Wetnurses, Banks tells us, came into vogue partly so that wives could resume attending to a husband’s sexual needs as quickly as possible. Laws enshrined paternal but not maternal rights, forcing Wollstonecraft’s sister Bess, who suffered bouts of “phrensy” after her daughter’s birth, to abandon the newborn out of fear that if she stayed, her husband would have her locked up in bedlam. The introduction of doctors into a practice that had formerly been the province of midwives was catastrophic for women. Too often doctors were impatient and eager to prove they’d earned their fees; sometimes their interventions were conducted with instruments and hands that hadn’t been washed after coming straight from another delivery or an autopsy in the morgue. At age twenty-six, Wollstonecraft watched helplessly as her childhood best friend succumbed to illness a week after delivering a son, who soon “followed his mother into the grave.” At age thirty-eight, she herself died from puerperal fever under gruesome conditions when William Godwin, her husband and the father of her second daughter, insisted on calling a doctor to handle a complication that Wollstonecraft and the midwife were confident they could address alone. The little girl she left behind grew up to become a mother of four children; though Mary Shelley survived all four births, only one of her children lived to adulthood. The first died before she had even received a name.

A century later and an ocean away, Banks tells us, American poet Adrienne Rich (1929–2012) delivered each of her three sons under general anesthesia. Twilight sleep beats puerperal fever by a long shot, but it still sounds like a nightmare, and one that foreshadowed precisely those parts of mid-century motherhood Rich would come to chafe under—namely, the parts that expected her to be cocooned and passive, an acquiescent cog in the burgeoning techno-consumerist machine.

We learn nothing of the labour-and-delivery experiences of the other two mothers profiled, Sojourner Truth (ca. 1797–1883) and Toni Morrison (1931–2019). There is something consoling, maybe even normative, in these omissions. No one could be bothered to call the doctor for an enslaved woman like Sojourner Truth, thanks be to God: of her five children, four survived to adulthood. She herself stood nearly six feet tall, and when, after a speech in Indiana in 1858, she was challenged to prove that she wasn’t really a man masquerading as a woman, Truth bared her breast to her accusers, told them the white infants she’d nursed in infancy had grown to become better men than they, and asked if they too would like to suckle. Of this moment Banks writes, “She disrobed not to her shame, but to their shame.” About Morrison we know only that she was born at home, hospital births being for “hookers” in those days, as she later put it. Although Morrison spoke frequently of her two sons, she never publicly shared details of their entrance into the world.

Birth is an experience that happens over and over and yet never repeats, and one that somehow grows both increasingly mundane and increasingly ineffable with time, as it recedes into memory and wonder.

There is a case to be made for reticence when all goes well. And perhaps it even helps explain why birth is such a stubbornly hard subject to write about or to prepare anyone for. The ingredients are similar enough from one birth to another that a narrative account quickly becomes boring, and different enough to make predictions impossible. Birth can’t be abstracted or distilled; you kind of just have to be there to get it, and even then (take with a grain of salt my assertion here, based on a sample size of one) you never fully get it. I could tell you what I remember, but to whom, aside from my daughter and me, would it really matter? Birth is an experience that happens over and over and yet never repeats, and one that somehow grows both increasingly mundane and increasingly ineffable with time, as it recedes into memory and wonder.

Sunsets are the same way, come to think of it. Maybe every moment is. And when one somehow makes it through our thick human skulls and our muffled senses, we see reality as it truly is: a miracle, a gift.

If birth as an isolated physical event were all that Banks tackled, I would still heartily recommend the book. But of course birth is not an isolated incident. We are each born into a wider society and, if we are lucky, a culture—the former designating, if I understand the sociologists correctly, the structures and institutions in which a particular group of people live, and the latter those beliefs and practices by which they live. Wollstonecraft provides a trenchant critique of how the structures of capitalism warped a culture of domestic care, leaving women and children potentially damned either way. The institution of marriage didn’t help her sister Bess much, but when Wollstonecraft conceived her first daughter, Fanny, out of wedlock and was jilted by her American lover, she saw how without it women were vulnerable to poverty, public censure, and despair. The experience nearly drove her to suicide.

Wollstonecraft also saw how a society that distributes agency lopsidedly between the sexes can push men toward tyranny and women toward servility, cunning, and a knock-on despotism toward the servants and children in their charge. Living as she did in the Age of Reason, Wollstonecraft ingeniously fought the times on their own terms. In A Vindication of the Rights of Women, published in 1792, she argues that reason is not incompatible with half of the population (and thus that women ought to be treated “like rational creatures, instead of flattering their fascinating graces, and viewing them as if they were in a state of perpetual childhood, unable to stand alone”); nor is reason incompatible with care and affection. “The revolution she imagined was a moral one,” Banks tells us. “A father should not be out ‘visiting the harlot’ and a mother should not be consumed by ‘the arts of coquetry.’ Rather, they should both be focused on nurturing, protecting, and educating their children.” It seems slightly mad even to have to argue a point as sensible as that one, but our age as much as Wollstonecraft’s provides proof that Samuel Johnson was right about human nature: “men more frequently require to be reminded than informed.”

A quarter of a century later, Mary Shelley intuited much about the threat that a growing scientific apparatus and worldview posed to the family. The sections of Natality on Shelley’s Frankenstein are among the most haunting in the book, not because the horror story itself is particularly scary but because it now feels so terribly prescient. Victor Frankenstein’s path to reanimating a corpse is ghastly—his intellectual overreach involves a series of macabre experiments and concomitant neglect of other realms, including what in today’s parlance would be called a healthy work-life balance—and the results are worse. “The creature is a motherless human life engineered by ambitious male inventors, born without lineage, language, or any tradition,” Banks writes. “He has emerged from the singular chamber of a male mind.” The “abandoned creature, made rapacious by his intolerable solitude,” stalks his creator, “seeking revenge upon him wherever he goes, until the creator finally reverses the direction of the chase, abandoning himself entirely to the pursuit of and intended destruction of his creature.” It all ends badly in the Arctic Ocean.

The parallels to today aren’t exact (although if we give smartphones another decade and a half to keep experimenting on our young, they might be). But they’re there: the disjunction between where we can achieve real good and where we frequently direct our energies instead; the way in which the relationship between generations has shifted from one of care, affection, and inheritance to one of avoidance, tension, and not infrequently harm. Substitute “investor” for “inventor” and the first thing that came to mind were the adolescents I sometimes try to talk to when I take my daughter to the park, the ones who tell me they’re reading a Shakespeare play in school but aren’t sure which one, or who are learning about poetry without having been issued a book; the ones whom edtech and Covid-era governance are threatening, in some very real way, to leave bereft of lineage, language, or any tradition.

By now the reader, both of Natality and perhaps also this review-essay, is in need of buoying up. And to the rescue come Sojourner Truth and Toni Morrison. Both were born black—Truth a slave and Morrison in slavery’s long shadow—and female and poor, triply inferior in society’s eyes. For a while Truth even believed the lie, rejoicing, as her amanuensis Olive Gilbert writes in the Narrative of Sojourner Truth (1850), “in being permitted to be the instrument of increasing the property of her oppressors” by bearing children for them to own. But against societal narratives of their inferiority come cultural narratives—from the family and the church—of their actual, immense, ineradicable worth. Man’s eye may not see truly, both aver, but God’s does.

Truth came to prominence around the age of thirty, after working her way to freedom in her home state of New York and successfully suing for the return of her five-year-old son, who had been illegally sold to a slaveholder in Alabama. In her autobiographical Narrative, she recalled her own childhood and how, after a day’s work, her mother would “sit down under the sparkling vault of heaven, and calling her children to her, would talk to them of the only Being that could effectually aid or protect them.” Other family members who had been sold off or otherwise taken away, her mother reminded them, sat and prayed under the same sky; in this way Truth’s mother would habitually “strengthen and brighten the chain of family affection, which she trusted extended itself sufficiently to connect the widely scattered members of her precious flock.”

In her mid-forties, Truth felt called by the Holy Spirit to leave New York City and begin life as an itinerant preacher, “testifying of the hope that was in her.” (Ironically, she took off without telling her children, who initially worried that she had lost her mind or committed suicide.) In some ways, Truth’s ministry consisted of passing on the message her mother had first given to her: to trust in a Good Shepherd who acts as a devoted mother, providing ceaseless, if sometimes imperceptible, care to beloved children who will all be gathered together in time. “God,” she said, “is the great house that will hold all his children” and the one who “sees the end from the beginning and controls the results.” Her steadfast trust in a loving, omnipotent God equipped her with both remarkable courage and a capacity for language so fresh that it hasn’t gone stale even a century and a half later. In Natality, Truth’s exhortations retain the power to shock as well as soothe.

Toni Morrison, too, springs to life in these pages as a brilliant, strong woman full of quiet faith and loud joy. Born Chloe Wofford, she grew up in a hardworking and hardscrabble family in Ohio, where her father’s only fear was being out of a job and her mother ripped eviction notices off the front door with, one imagines, a firm hand, eyes rolled heavenward, and a loud sigh, not at what her family might become but at what the landlord already was. No economic privation or racial prejudice could stop the Wofford family from seeing a new child as anything other than a blessing, and in 1989, as teenage pregnancies neared their peak in the United States, Morrison surprised an interviewer by expressing support instead of condemnation. “Nature wants it done then, when the body can handle it,” she said, adding that “she personally wanted to take them in her arms and tell them, ‘Your baby is beautiful and so are you.’”

Raising her own two sons as a single mother, Morrison was candid about the challenges she faced, but also undaunted. She initially tried writing in a locked room, and when that didn’t work, she wrote while her kids played around her or while they slept. In an anecdote I found oddly heartening, Morrison recalled “writing around some vomit her son had left on the page. She simply needed to get that sentence down before she forgot it. The wiping up could wait, but the sentence could not.” Morrison didn’t try to shut her children out; she took reality as it is, inconveniences and all. In life as in her fiction, she accepts the existence of chaos and evil with an equanimity I’ve admired before and, like Truth, with courage and a joy that flames out in humour even in the darkest times.

Morrison’s fictional oeuvre centres on birth. Her first novel, The Bluest Eye, opens with a pregnancy, and her last novel, God Help the Child, closes with one. In between, Banks argues, her fiction is animated by the conviction that “what you do to children matters. And they might never forget it.” Beloved, Morrison’s most popular book, though never my favourite, finally became intelligible to me after reading excerpts from her interviews alongside Wollstonecraft, for reasons it will take a slight detour to explain.

It goes without saying that no mother, nor father, is an island: ideally the birth of a child forces you to acknowledge, if you hadn’t already been in the habit of doing so, that other people are real, valuable, and worthy of your time and energy. This is true, to greater and lesser degrees, even of people you don’t know very well at first, and for one particular subcategory of that demographic—newborns—it applies even when your reserves of time, energy, and patience are lower than you’d realized they could go. In her introduction, Banks muses on why twenty-first-century Americans talk much about death (though not necessarily in sound ways, I’d add) but rarely about birth. She provides a number of good reasons why this might be the case. I’ll add one more, which is that even the fact of our mortality is somehow not enough to strip us completely of delusions about our own agency and power, as the push to normalize euthanasia shows.

Birth, by contrast, leaves one with zero illusions. This alone may go a long way toward explaining why pregnancy is often romanticized and the postnatal period ignored. It’s not just that the “graphic physicality” (as Banks writes) of birth and its immediate aftermath make it a tricky subject to broach at dinner parties or around the watercooler. It may also be simply too painful for most people to think deeply about how vulnerable any infant is—and therefore how vulnerable we all once were. How we needed someone to do for us what we could not yet do for ourselves and how, at least sometimes, they didn’t.

“In everyone there sleeps / A sense of life lived according to love,” Philip Larkin writes in his poem “Faith Healing”:

By loving others, but across most it sweeps

As all they might have done had they been loved.

Morrison seems to have been in the lucky quotient of those who grew up feeling loved, and certainly in adulthood she saw the ability to nurture as an essential bridge connecting the generations that preceded us and those who will come after. Such “ancient properties,” she said, act as “tar” holding “something together that otherwise would fall apart.”

So, yes, clearly she knew—as parents today sometimes forget—that birth must take us outside ourselves. But Morrison also knew that it is possible to err in the opposite direction too: to go so far outside ourselves that we are left empty and hollow. In Beloved, Sethe’s infanticide—based on the real-life story of Margaret Garner, who escaped from slavery in Kentucky and killed her own daughter when the family faced recapture—is not love but the kind of knock-on despotism that is also self-loathing and self-sabotage. In Banks’s telling, “‘A woman loved something other than herself so much,’ Morrison marveled when she was writing the book. ‘She had placed all of the value of her life in something outside herself.’”

Birth must take us outside ourselves. But Morrison also knew that it is possible to err in the opposite direction too: to go so far outside ourselves that we are left empty and hollow.

The hollow man or woman is as incapable of a “life lived according to love” as the solipsistic one. By attempting to shift what belongs to us as parents and individuals onto our children, we risk turning them into puppets and, in the process, becoming puppets ourselves. While we try to work our children’s strings, someone or something else is likely working ours—possibly, Beloved suggests, the devil himself.

Morrison doesn’t damn Sethe for her desperate act, but she doesn’t let her off the hook out of pity either. And she doesn’t imagine that her protagonist’s salvation can be worked out easily or alone. Beloved ends with Sethe’s surviving daughter, Denver, and other local women outside her house praying and paving the way for her redemption and restoration to the community and to God—if she will have it.

The word for this delicate balance of internal and external agency, of responsibility for others and for oneself—as best as I can determine anyway—is grace.

Here we come to what might be called the metaphysics of birth. Chloe Wofford took the name Morrison through marriage, but she acquired the nickname Toni years before that, when she converted to the Catholic Church at the age of twelve and chose Anthony of Padua for her confirmation saint. Banks’s brief introduction to St. Anthony omits one detail from his life that likely appealed to Morrison: a mystical experience he reportedly had while staying at the home of a wealthy benefactor. The host, surprised to see light glowing from under the door to St. Anthony’s room at night, opened it to discover the saint, deep in prayer, holding the infant Jesus in his arms as the two gazed at each other with evident love.

Hannah Arendt, surprisingly, also had a soft spot for the infant Jesus. I’ve given short shrift to her ideas here, not least because they deserve to be encountered more fully through Banks, who gives an impressively readable introduction to parts of both The Origins of Totalitarianism and The Human Condition. Arendt asserts that “the supreme capacity of man” is the human ability to “begin,” by which she means our ability to deviate from the status quo, to do something new, potentially even something that has never been done before. This capacity to begin, she says, is “ontologically rooted” in natality, which she defines as “the fact that human beings appear in the world by virtue of birth.” Men and women, she believed, “are not born in order to die but in order to begin”; this beginning is what differentiates human action from mere animal behaviour. Though Arendt did not subscribe to the Christian faith (nor to any other faith), she felt that the joy, possibility, and hope implicit in natality were best captured by the verse in Isaiah presaging Christ’s entrance into the world: “Unto us a child is born.”

How exactly Arendt understood humankind’s capacity for novel action to spring from the fact of our birth has long puzzled philosophers, and it remains mysterious by the end of this book too. Banks admits to sometimes feeling frustrated that Arendt never writes about women or pregnancy or children; her concept of natality is alive and humane, but decidedly lacking in graphic physicality. To counter Arendt’s lack of interest in the body, Banks sometimes goes too far in the other direction, by lapsing into prurience (eavesdropping on writers’ explicit love letters made me uneasy) or by deeming the inclusion of birth imagery a condition sufficient to qualify a piece of writing as “natal.”

Banks’s celebration of “beginning” in general—that is, as a gerund derived from an intransitive verb—also unnerved me. Surely the direct object matters in this context; surely it makes a difference what one begins to do. Supposing that it doesn’t can lead to the kind of directionless ruminations on offer in the epilogue, which show the limits of stringing natal pearls together without a clear trajectory. The seven thinkers she’s assembled, writes Banks, “were all shaped by birth and they in turn have shaped our collective understanding of what it means to be born human. With verve and imagination, they showed how each person, in simply being born, creates an opportunity for history to begin again.” That is true enough, as far as it goes, but Banks offers few normative or moral conclusions from the evidence she lays before us. She does helpfully introduce Arendt’s metaphor of “deserts and oases,” from The Promise of Politics. Large swathes of human existence have always been arid and uninhabitable, Arendt argues. The danger of modernity is that instead of encouraging us to build new “fields of life” through friendship, love, intimacy, and privacy, it expects us to eat sand and like it. But the only way to see all seven “visions of natality” as “oases,” as Banks does, is to divorce birth from telos, our physical beginnings from our ultimate, eschatological ends.

So one lesson that emerges from this book, somewhat accidentally, is that the human capacity for beginning doesn’t mean you can go absolutely anywhere with equally profitable results, and it also doesn’t mean you can start from nowhere. Morrison was adamant that her birth did not “cut her off as a separate piece from a whole cloth.” She took pride in being part of a larger tradition of strong, brilliant matriarchs who were bringing about a “slow but ‘miraculous walk of trees’ from the valley up into the mountains”—that is, gradual “but ‘irrevocable and permanent change.’”

The two thinkers in Natality who attempt more drastic breaks with the past meet with dire consequences. For Adrienne Rich, honouring the sacredness of the individual’s “will to change” meant announcing to her husband that she’d rented her own New York City apartment and that from then on “the boys would stay with him.” Three weeks later her husband, fearing she’d gone insane, shot himself and left Rich with three sons to raise on her own and an emotional wound that never healed. All her life, we’re told, she would become enraged if interviewers asked about her late husband.

Nietzsche, meanwhile, though he apparently loved Christmas as a boy, sought a clean break with traditional religious mores. What he replaced them with was (like Rich) an elevation of the individual will and (unlike Rich) a descent into actual insanity. “His sense of human power grew in reverse proportion to his personal and professional failures,” Banks observes, as Nietzsche crafted an increasingly convoluted Dionysian religion. He confused his friends by signing letters “alternatively, ‘The Crucified’ / ‘Nietzsche’ / ‘Dionysus,’” and, after being institutionalized, he left others with the difficult work of caring for a madman who screamed (“considerable priapic content,” the medical notes laconically observe), “paced, drank his urine, smeared his feces on the wall, and slept on the floor.”

By the end of the chapter, I was not persuaded that any amount of birth imagery in Nietzsche’s writings would result in my edification as a mother or a human being. Nor could I tell whether Nietzsche’s madness had produced his philosophy or the other way around. Banks, however, takes his writings at face value. She gives space to ideas that struck me as incoherent, unsound, and antithetical to what Arendt meant by natality: Nietzsche’s preference for Dionysus over Jesus; his desire to do away with “the ‘wretched belljar’ of human individuality” and return to a “mysterious primal Oneness”; the Faustian bargain he proposes in The Gay Science, where a demon asks readers if we’d like to be perpetually reborn on earth and the courageous answer is, supposedly, “You are a god and never have I heard anything more divine”; his love-hate, attraction-repulsion oscillation toward and away from women and physical birth. By the time Zarathustra was marrying eternity, birthing lightning bolts, and cutting “the umbilical cord of time,” I was making mental lists of all the childless male writers from whom I have learned a great deal. (Philip Larkin made the list.) When Banks quotes Thus Spoke Zarathustra with approbation—“‘I say unto you: one must still have chaos in oneself to be able to give birth to a dancing star,’ Nietzsche wrote, with tumultuous depths and uncanny insight”—I could see the tumult, but not much else. His take on self-creation and self-re-creation is as old as the hills, going all the way back to the serpent in the garden.

But Nietzsche and Rich were right, at any rate, about the importance of the will. They were wrong in divorcing it from the intellect (or perhaps from belief in an objective, ordered reality). A key part of what Arendt’s concept of natality so brilliantly intuits is that birth entails the bringing into the world of not only new bodies but also new souls.

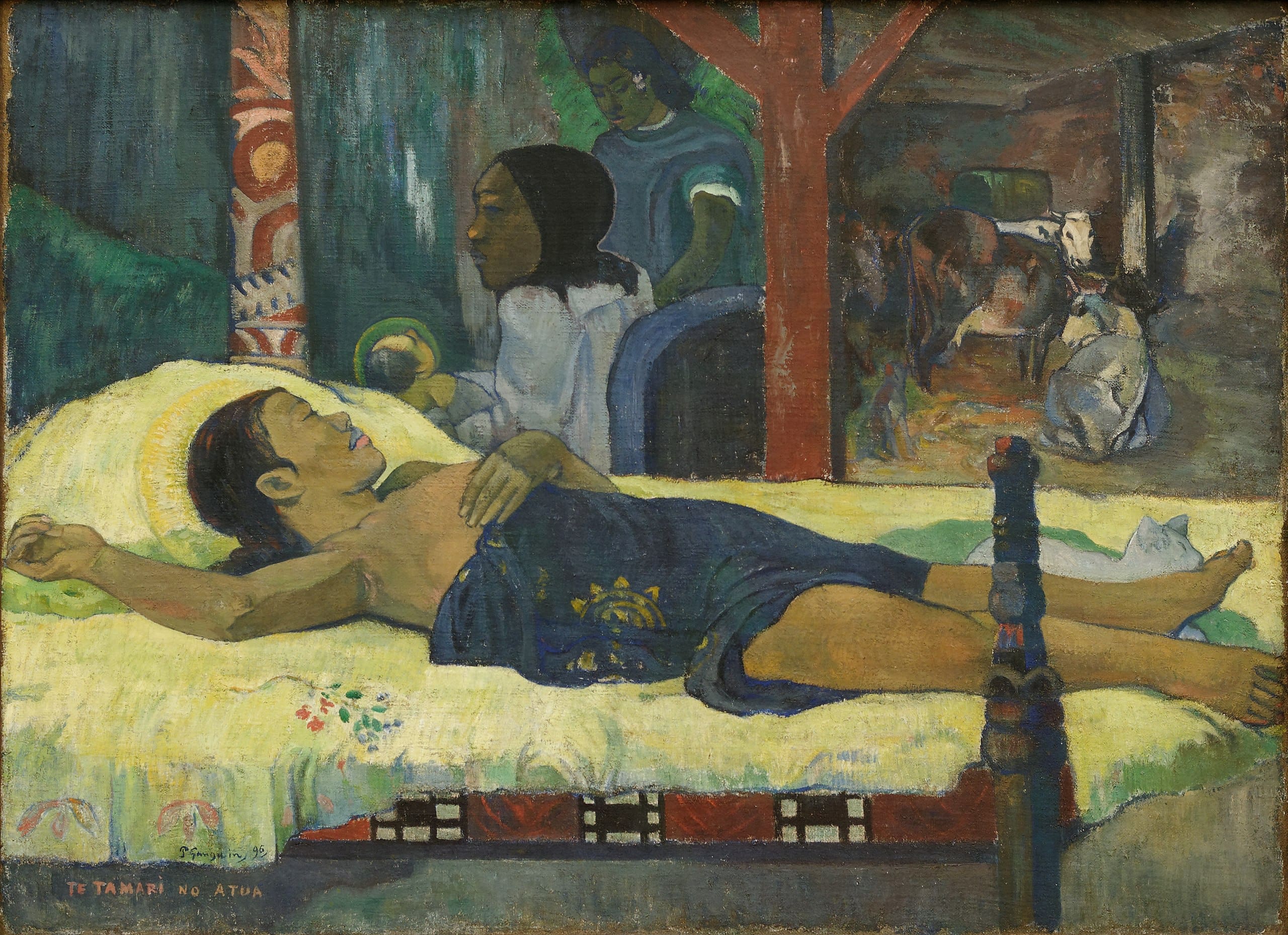

In this respect, I would argue—contra Banks and even contra Arendt—that the paradigmatic moment of natality in the Gospels is not even really the nativity, which the early church fathers unanimously agreed set no precedent whatsoever for births that followed. (The simile they settled on to illustrate how Mary could remain a virgin after birth is that Jesus emerged from her womb as “light passes through glass without harming the glass.”) The real template for understanding what natality invites us each to do comes before that, with the annunciation.

When the archangel Gabriel appears to Mary and tells her about God’s plan to come into the world, she possesses Morrison’s equanimity in spades. Mary isn’t fearful or doubting like Zechariah, nor is she hasty like Eve. She asks one clarification calmly—about how the Messiah’s birth is to be accomplished while preserving her virginity, which she’d already dedicated to God; notably not about how to avoid being stoned to death when the community learned she was carrying a child that didn’t belong to her betrothed, Joseph—and then gives her calm assent. “Behold, I am the handmaid of the Lord,” she says in Luke’s Gospel. “May it be done to me according to your word.”

That God should invite us into his plan for the salvation of the world in this way is wonderfully strange. He could do it all instantly himself, but for some reason he gives us a chance to help. Strange, too, that he gives us such tragicomic bodies and fallible wills to accomplish this end. “It’s all strange,” Lila muses in the same passage of Robinson’s novel. The way her son arrived on earth, the blue of his newborn veins through too-thin skin, “that blue that was never meant to be seen,” the slant of light in the room as he was born. “It is so strange that it belongs in the Bible, with the seraphim and the dry bones.”