I

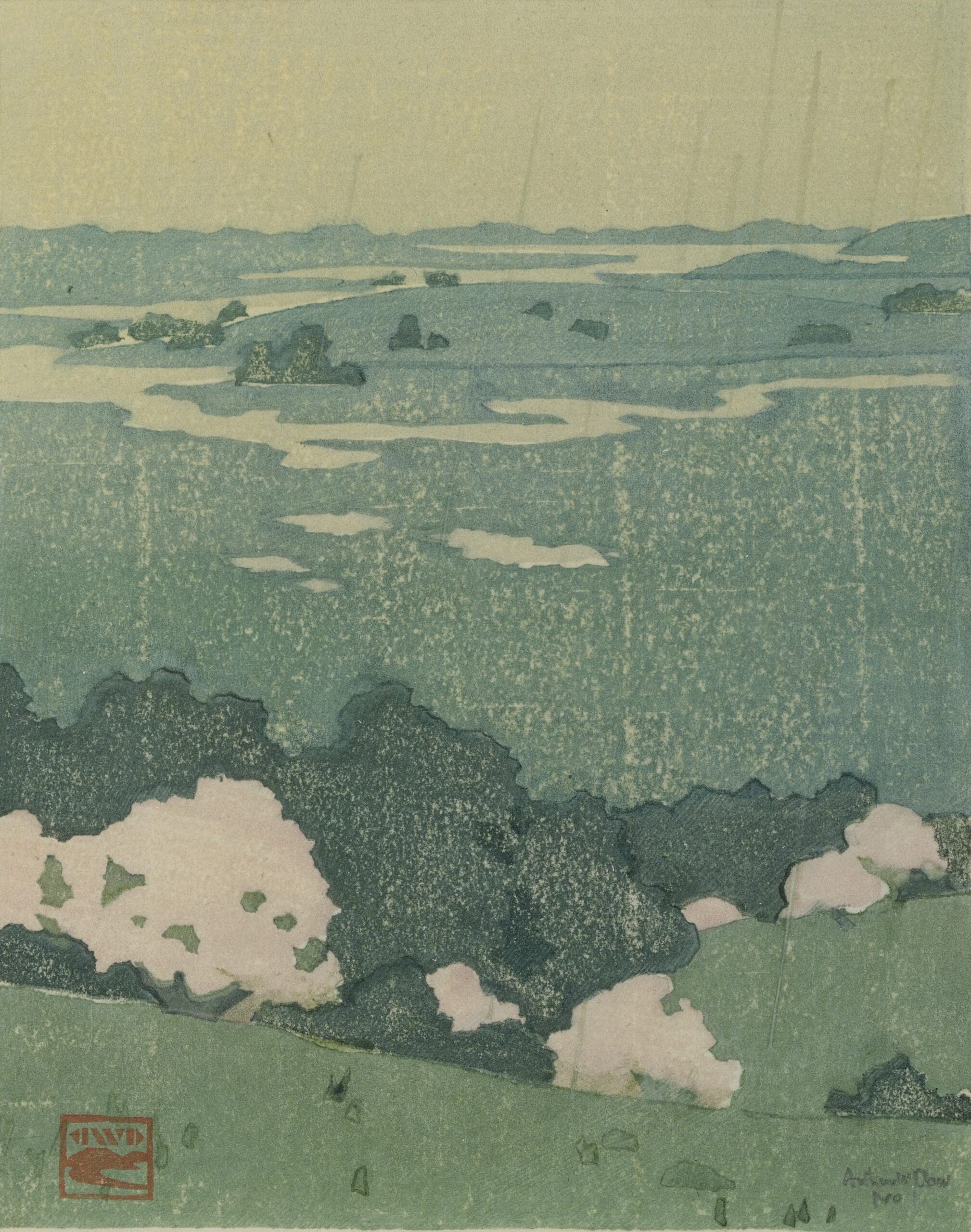

I’ve only really known a shade of my dad, like glimpsing at dead, fallen leaves to study the intricacies of a large, old tree. My dad is an addict. Addiction is like rot, a slow decay imperceptible at first, that works its way from the inside out. When you at last survey the great damage, it may no longer be the person you are surveying, but the remnants of the attack itself. I despise addiction beyond any other ailment because of this. A child who used to look into the eyes of a father grows up to look merely at the wreckage of an alcoholic. Humanity drains away as sin and despair fill the cup. A child of addiction finds himself, in the end, to be an orphan.

My dad worked the off shift at his factory job. Occasionally I would wake up to the sound of him coming home late at night. The garage would open, the door would close, and the TV would turn on. While I could have easily rolled back over and gone to sleep, often I’d crawl out of bed, leave my bedroom, and visit with my dad. I remember he never turned the lights on when he walked in the door. One learns to exist in silence and dim light at home when working while your family sleeps. I recall this from my own time working in the same factory for a period later in my life. A son can never fully escape the calling to mirror his father. As I emerged around the corner of the opening into the kitchen, I’d see him grab his dinner from the fridge and throw it into the microwave. I’d announce myself and take a seat at the little table in the kitchen.

I was always aware and afraid of my dad’s alcoholism. The worst of the behaviour always manifested itself when my mom confronted him after whatever summit of abuse and inattentiveness he had achieved. However, the desperate longing of a spouse was perhaps not as harsh of a lashing compared to the shame brought forth by the eagerness of his child desiring to be seen. I believe this is why he never sent me straight back to bed. I relished those times when I could simply be alone with him. Initially he tried to be discreet about his drinking during these early-hour rendezvous with me, but eventually he settled into drinking unabashedly and we would just be together. He’d ask me about my day, talk to me about what was on my mind, and then eventually send me to bed. To this day, I’m not sure how long he would stay awake and drink.

Because of his alcoholism, I never knew my dad too deeply growing up. I did know that once he was drunk, I’d penetrate only a certain extent of his person. While I relished my time with him at night, I worshipped my time with him in the mornings. Being awake early with him meant I got to see him at his best. He’d look into my eyes and listen to me. Sometimes he gave useful advice or spent quality time with me on some activity. From early morning to noon, he could be a father. After that he decayed into something unrecognizable.

As time went on, my dad’s drinking and the behaviour that followed became so horrid that we fled our home almost every Friday evening to spend the night or weekend with family friends. My parents had many intense confrontations and screaming matches. I had frequent panic attacks brought on by the torment of wanting the chaos to stop and the desire to protect my mom. There is nothing more unbearable than unrealizable conviction. A child who can only beat at the shins of the monolith of danger in their life exists in shadow. That shade is a constant reminder that circumstance is pressing in. Severe anxiety engulfed me. Eventually, my mom divorced my dad and we fled our home one last time.

When I grew older and childishness fell away, I was not as easily satisfied with the morning snippets of peace with my dad. I began to understand what he wasn’t doing correctly. As a teenager with no religious background, I began to contend with the idea that there must be some ideal, a higher calling of participation with one another. At the very least, I knew my dad wasn’t pursuing whatever that was. As my curiosity about this higher participation grew, my patience for him dwindled.

Alcoholism and divorce brought our family to its knees and to a level of poverty not previously known to us. I grew angry and frustrated. It was during this time that I discovered two great fathers: C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien. I had read The Lord of the Rings and some of the Narnia series in late elementary school. At the time I thought they were just fanciful and entertaining stories. However, I rediscovered these men early in high school while exploring the fantasy section in the library. I checked out The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe and all three books of The Lord of the Rings. I distinctly remember feeling the urge to begin reading as I exited the library. I walked to the graveyard across the street from our school and sat down against the exterior wall of the caretaker’s shed to read The Fellowship of the Ring. What followed can only be described as the bloom of graceful relief, like a man coming up for air after swimming upward from the darkest depths of the sea. The weight of the ocean lifted from my chest, and I breathed in a new reality.

Like a soldier looking out at the immensity of the White Witch’s army on the horizon, or the shadow of Mordor bellowing up and spreading toward Minas Tirith, I was facing the difficult choice of buckling under the weight of disorder and evil or donning the armour of battle and engaging the great enemy. First, I discovered that these stories are metaphors for the battle we all face. Then I discovered that the underlying reality that connects our world to these stories is the demand of people’s souls that good must prevail over evil. These stories pointed me toward the idea of another realm existing. Perhaps the cultural Christianity one is exposed to in our society is merely a poor representation of the true underlying reality itself.

I was not under some pointless yoke of suffering. I was engaged in spiritual warfare. All the struggle of both my life and my dad’s life was at the hand of a very real enemy, one so cunning and underhanded that he sought not merely the poisoning of my father but also the downfall of his son. The idea chilled my blood. Generational sin is a desirable investment to the enemy we are up against. It is the gradually compounding return that he values deeply—a lesson I gleaned well from Tolkien’s writing. As Sauron tempted generations of men with the false promise of the ring, only to lead them to their downfall, so the great enemy of our world was leading my dad and me to ours. However, Sauron and Satan share their greatest fear: that we would interact with their instruments of torment in a way they would never expect. As Frodo came into possession of the ring and made it his purpose to destroy it, I might also find purpose in eventually rising above the instrument of my pain: a family crippled by circumstance.

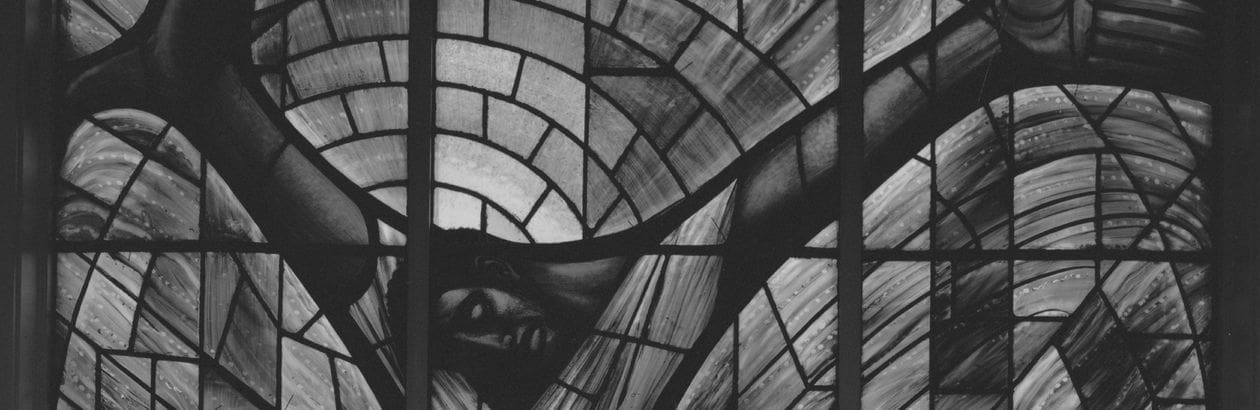

The fantasy stories to which I devoted myself, because of the thinly veiled hope of Christ wrapped up within them, began to reveal what they truly were. They were the whispers of God.

Stories that uplift the beauty of light in the darkness gave me great courage during these years. And these men wrote so profoundly on the subject. As I slowly found myself becoming a Christian, I began to understand what the ideal was. The fantasy stories to which I devoted myself, because of the thinly veiled hope of Christ wrapped up within them, began to reveal what they truly were. They were the whispers of God. And I understood that a father missing a visitation, or a desperate mother searching for security from any viable source, is not the ideal.

Unfortunately, my initial response to this call was extreme and, to put it bluntly, incorrect. I decided I had to escape my family. I viewed my family with contempt for not wanting more for us all. My epiphany should have led me to pursue the ideal with grace. But I was a child, and I responded to my reality being broken with hatred and disgust. I left home at the end of my junior year in high school, with no place to go but my car and the couches of friends. I decided that destitution and displacement were preferable to a family riddled by addiction, motivated by fear, and determined to settle for expedient comforts. Disagreements with my mom and brother about our lives drove me out the door. And our collective stubbornness permanently locked the door behind me. I never lived with them again.

However, the threads of God’s plan for us are never unravelled by our mistakes, and this time in my life was a conduit of God’s grace for me. The paradox of spiritual wealth provided through poverty is a tool only God can wield. I eventually grew less angry at my dad as I contended with the struggles of homelessness. I no longer had time to be concerned with what others were doing to me when I had to combat the barrage of consequences created by my circumstance. I still had God, friendship, and the great angel of my life, whom I’d eventually marry, to lift my wings. My dad, however, was so broken that at some point he convinced himself that flight was not in the cards for him. But I no longer viewed his sickness as a simple choice. I came to understand it as a sickness of the heart brought forth by the deprivation not just of hope but of meaningful love. It’s hard to keep misunderstanding an addict once you realize that their addiction was likely spawned from the throes of hopelessness.

Shortly after that realization I started dating my eventual wife, Lauren. It was our senior year in high school, and we had a couple classes together. Initially we were just friendly. I still remember the moment I started to feel something beyond friendship for her. I was walking in the rain to my car one afternoon. I couldn’t afford an annual parking pass at the high school, so my workaround was to park in one of the neighbourhoods that bordered our school and walk from there. As I trudged down the sidewalk, Lauren pulled up next to me and asked me why I was walking in the rain and told me to get in her car so she could give me a ride to where I was parked. We began to do this daily. During these short car rides she became aware of my circumstances.

Eventually we grew closer and began to date. A parent can only imagine the horror of having their only daughter bring over her giant, homeless boyfriend for dinner. The humour we find in it now is as palpable as her parents’ worry was then. However, Lauren’s mom and dad were as gracious to me as one could possibly hope for given the circumstances. At times her parents cautioned her about the seeming seriousness of our relationship. Lauren insisted that they did not understand me, that they didn’t see my potential, and that she was going to marry me. What must be understood is that Lauren is no naive woman; she has no interest in the ramblings of young love. Her statement carried the certainty of one who saw beyond the veil of circumstance and into the promise of redemption. I will be forever indebted to her faith in me. It was the belief of this little saint that gave me the courage to take up arms against the dragons of my fallen nature and opened a deeper insight into God. We married a couple years after high school, despite the concern of many and with the support of very few.

As I grew closer to God and began living out my faith more seriously, I found that I had the ability to withstand more. I could work harder. I could work longer. I could be patient. I could be tactful. I could survive. I could succeed. I could escape the circumstances constructed by my family and its consequences and erect a structure of stability for my own family. I had the foundation of Christ and personal choice bolstered by divine intervention to aid in the task. As the bitterness of childhood faded, the joys of raising my own family and showing them truth overtook everything.

As I survey my life today, my wife and children are well cared for and provided for. They have security, stability, and the benefit of a husband and father who sees their faces clearly, because I view them, to the best of my ability, through the lens of Christian responsibility. My ever-growing gratitude that God has helped me offer this boon to my family only further helps me understand my dad’s compounding misery and increases my hope for his supernatural healing, that one day he, too, will awake to the divine.

The greatest lesson I learned from him, however, hasn’t come as a result of him casting aside addiction and committing to a clean and sober life. Quite the opposite, unfortunately. I recently confronted my dad, as I have on countless occasions, and pleaded with him to seek treatment. This time, though, he responded to me honestly—probably for the first time in his life. I was prepared for a series of empty, surface-level promises: that he would abandon the path he was on and right his course. But this was not his response. Instead he told me it was time to let him go. He was doomed, he told me. And he didn’t want to upset me anymore by causing me to cling to the idea that, one day, he would wake up with the urge to be sober. He told me he was too old to pursue anything different now, that he planned to spend the rest of his time enjoying the things he enjoys and no longer contending with the misery and guilt of trying to do something that he believes he cannot do.

I was distraught. Despite his faults, my father has always remained an example of toughness, hard work, and his own unique brand of strength. I thought he was being a coward. I told him that to give up on something far greater than the empty relief of forsaking conviction would be more miserable than consistent relapsing amid genuine effort. He said he had no desire to discuss it further and to let him go.

It’s hard to keep misunderstanding an addict once you realize that their addiction was likely spawned from the throes of hopelessness.

I left the conversation at a loss. I didn’t know what to do. So I did what all sons do when confronted with darkness. I went to my mom. My hope was that she would push me to pursue some kind of righteous action. Her advice, however, was like a snowstorm in spring: unexpected and perhaps disordered, but still beautiful in a sense. She told me to let him go. To find a way to come to terms with the likelihood that this will be his legacy. She reminded me to be thankful for my deliverance from the circumstances of our lives and my childhood. She told me to abandon the state of suffering I continued to subject myself to by continuing to hope for him. Most meaningfully to me, she cried for my heartache. It was a beautiful moment of maternal support. But while a snowstorm in spring may be unexpected and beautiful, that doesn’t mean it’s ideal. There is a disorder about such a storm, and there was a sort of disorder about this guidance.

I left the conversation unresolved as to what my response should be. I was in tears at the thought that I should begin to mourn, not just the loss of a real father, but the loss of my father’s dignity and purpose. My mom was heartbroken at the thought of me eagerly waiting for his deliverance, knowing it had led me to so much sorrow and disappointment over the years. I started to believe that perhaps she was right. My dad at sixty years old has little more in this life than what he came into the world with. He has no home of his own, no material wealth, and no spiritual life. He seems more determined to drink as years of struggle and consequence have compounded. I was very close to accepting my mom’s invitation to move on from the level of accompaniment I have committed to with him over the years.

But then I remembered a portion of an essay written by my great teacher and spiritual father C.S. Lewis. He writes the following in The Weight of Glory:

It may be possible for each to think too much of his own potential glory hereafter; it is hardly possible for him to think too often or too deeply about that of his neighbour. The load, or weight, or burden of my neighbour’s glory should be laid daily on my back, a load so heavy that only humility can carry it, and the backs of the proud will be broken. It is a serious thing to live in a society of possible gods and goddesses, to remember that the dullest and most uninteresting person you talk to may one day be a creature which, if you saw it now, you would be strongly tempted to worship, or else a horror and a corruption such as you now meet, if at all, only in a nightmare. All day long we are, in some degree, helping each other to one or other of these destinations. It is in the light of these overwhelming possibilities, it is with the awe and the circumspection proper to them, that we should conduct all our dealings with one another, all friendships, all loves, all play, all politics. There are no ordinary people. You have never talked to a mere mortal. Nations, cultures, arts, civilization—these are mortal, and their life is to ours as the life of a gnat. But it is immortals whom we joke with, work with, marry, snub, and exploit—immortal horrors or everlasting splendours.

Lewis’s words came to me like the charge of unexpected reinforcements in the face of defeat; their truth bolstered my soul as the sound of thousands of horses charging across the plains bolsters an exhausted foot soldier. Christ’s great calling lifted me yet again in this moment of despair. Remember your fairy tales, I thought to myself. I breathed deeply the grace of God because I was gifted the strength to stand amid darkness and trudge forward. I have been called forward by the reminder that my dad’s glory might be hanging in the balance. My willingness to carry the weight of his “potential glory” on my back in anticipation of his awakening to it may be the eventual key to his metamorphosis. His awakening would be contingent on his exposure to the one true reward: the providence of the patient love that is the very essence of Christ.

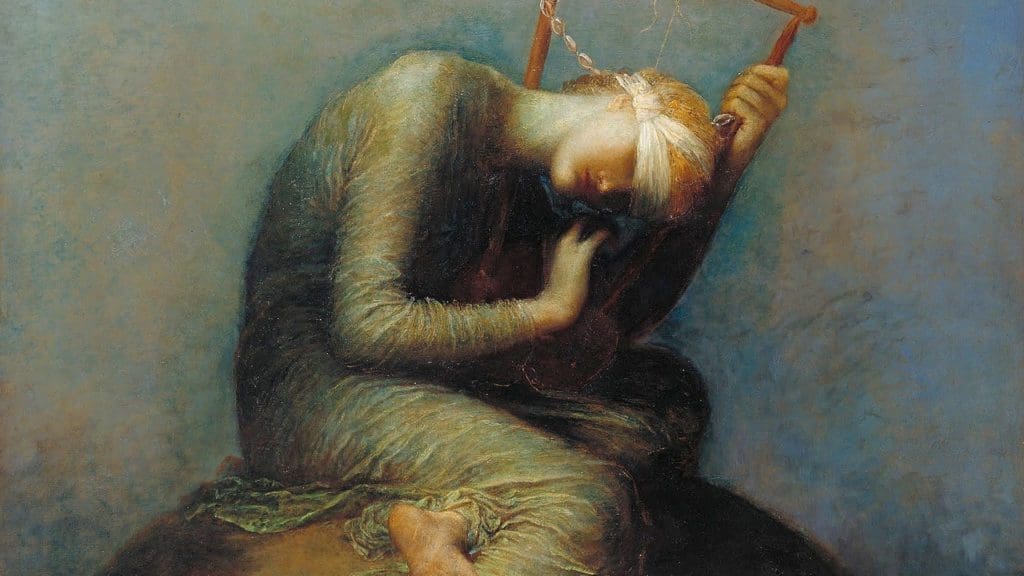

I used to be under the impression that providence is delivered through power, but this is not so. Providence comes through poverty. Power is what is unleashed through the hope of Christ on behalf of us poor, lost souls. Our desperate poverty compels us to strike at the harp strings of this life, clinging to the possibility of some ringing sound of hope. The reverberating beauty that follows is Christ’s response to our desperation. The empty, still air becomes filled with the miraculous, and all will stop to admire in the end.

And for this I cannot, and will not ever, abandon hope for my dad. As Samwise Gamgee thrusted Frodo onto his shoulders to attempt the final climb up the slopes of Mount Doom, we as Christians must be willing to answer the same call. The scent of strawberries blossoming in the Shire made the trek worth it for Sam and Frodo. Even the scent, or whisper, of my father one day seeing the far, green country Tolkien wrote of is worth all the potential misery the enemy can thrust at me as a consequence for this great hope.

Despite my father’s attempt to teach me that it is time to abandon hope, he continues to be the primary avenue for wisdom and strength that God has chosen to communicate through in my life. Desperation breeds a desire for truth. Truth is the only thing in this life that matters in the face of despair. So I will continue to climb this mountain with my dad. Whether he likes it, or even realizes it, or not. And when his knees buckle and he falls to his face, he will at the very least not be alone. The question will be whether he allows his son, reinforced by our Lord, to carry him the rest of the way. If he does accept it, it will be a glorious occasion. The great old tree will be restored. The orphan will, at last, be face to face with his father.