A

Amid a dizzying swirl of cultural change, vibe shifts, and a media ecosystem impotent to sustain user attention because of the velocity of information it facilitates, Western cultural consciousness has managed to maintain an unwavering focus on identity. From Plato to Descartes to modern-day philosophers, whether in the academy or in pop culture, the idea of personal identity consistently finds relevance across time, geography, and category. “Who am I?” and “How do I know?” are persistently live questions.

The idea of having a true self goes back at least to Cicero, who made a distinction between individual characteristics that distinguish us from others and fundamental properties that define us at the core. This latter understanding of identity, the truth of who we are, is “one of the distinctive ideals of modern life,” writes philosopher Joshua Knobe.

How do we know our true self? How do we establish identity? In recent decades, the source of authentic identity is assumed to be found within. To know who you are, look inside, discover, and share.

Nobody knows this better than modern marketers, who have a financial incentive to capitalize on popular cultural themes and so, quite literally, cannot afford to interpret the times incorrectly. Coach, creator of luxury handbags and luggage, invites “courage to express your many selves.” ’47 Brand exhorts patrons to “let your you out.” Cosmetic providers such as Nivea (“Live your beauty”), L’Oreal (“You’re worth it”), and Bobbi Brown (“Be who you are”) appeal to authentic inner worth. “Is it in you?” asks Gatorade. “Obey your thirst,” demands Sprite. And outdoor work-brand apparel provider Ariat, perhaps more than any other, captures the spirit of modern identity: “Don’t let the world tell you who you are.”

While marketers want their audiences to express their authentic selves, they want them to do it through the frenzied consumption of their brands. What we label as autonomous self-discovery is inescapably contingent on the cultural vibes that shape our tastes and aims at a given moment. “Be yourself!” blare brand managers, echoing our dominant modern sensibility—“just do it with our product, service, or experience.”

A modern approach to identity associates self-discovery with self-creation: we don’t have a narrative; we create our narrative. Freedom is “the process of creating your essence,” writes twentieth-century philosopher Simone de Beauvoir. Decades later, Justice Anthony Kennedy, echoing her and many other influential voices, famously equated liberty with “the right to define one’s own concept of existence.”

The idea of authoring our identity, however, abstracts from relationships, commitments, and attachments. We falsely assume we have the capacity to act independently of the persons, places, and things in our lives.

Moreover, our age of self-established identity is correlated with our age of anxiety. The assertion that we have the freedom to determine our self-understanding fails to deliver on its promise of liberation. “Modern liberty and modern anxiety,” write Benjamin Storey and Jenna Storey, “are two fruits of the same tree.” A general scan of modern life overwhelmingly reflects not fulfilled lives of meaning, maturation, coherence, and purpose, but the burdens and anxieties of self-creation. Today’s anxiety is not due to conformity, says Yuval Levin. It is a function of placelessness.

What is pitched as self-defining autonomy is more appropriately understood as an identity crisis and, invariably, gives way to a crisis of authority. It is little wonder that philosopher Charles Taylor long ago characterized our modern moment as a shift from authority to authenticity. Authenticity, he writes, “requires that we discover and articulate our own identity.” Few things are more authoritative than invoking one’s personal testimony or “lived experience.” If my self-understanding has no reference outside myself, then all that is left is the self. In this reality, I alone become the standard for identity and normative action. Who I am and what I do. Among other things, remarks Tara Isabella Burton in Strange Rites, this gives rise to an intuitional, not institutional, religiosity. “When we are all our own high priests,” she writes, “who is willing to kneel?”

What We Want Out of Identity

These critiques, and many others, point to significant philosophical deficits regarding the inward reflex associated with questions of identity and self-understanding. Discovering myself may be a frequent mantra or the stuff of marketing campaigns, but the enterprise remains impractical and challenging. What, after all, do we expect to find when we look inward to discover ourselves? We experience dissonance between our beliefs and desires, intentions and actions. Bertrand Russell referred to his life as a “mass of contradictory impulses.” Our day-to-day conduct often falls short of our moral aspirations. In negotiating internal conflicts and contrarieties, which self should we be true to?

How can self-creation be authentic when our supposedly self-originating choices are predominantly governed, formed, and suggested, as Edward Bernays writes in Propaganda, by “[people] we have never heard of”? Marketers and moguls both reflect and stoke the desires of their target audiences, pulling the less visible wires that marionette unwitting consumers.

And even if we are free to choose and self-create, we understand our manufactured individuality not as fixed but as fluid. Writer Alok Vaid-Menon, for example, uses words like “scavenge,” “assemble,” or “collage” to describe identity, suggesting a process of creation and re-creation: “I quite literally gave birth to myself.” Philosopher Susan Bordo likewise describes the human body as “a medium of culture.” Viewing ourselves as a tabula rasa for self-definition, however, comes with a trade-off. Assuming self-creation is fluid (after all, creativity is not a constant), identities cannot escape the problem of persistent instability.

So, what to do? If inwardness is an unhelpful direction when raising questions of our self-understanding and stability, where should we turn?

Asking “Who am I? and “How do I know?” can quickly collapse under the weight of contestable responses. Philosophical attempts to define a person are mired in complexity, often invoking Christopher Nolan–like sci-fi conundrums to complicate our understanding of identity and raising more questions than answers. We are more likely to understand and ascertain selfhood by changing the question. Not “Who am I?” but “What do I want?” Specifically, what characteristics do I desire for my identity? In establishing a sense of self, what outcomes am I ultimately after? Describing Taylor’s work, Adam Gopnik writes, “What matters most in life to actual people . . . is not the standard liberal question ‘Who am I?’ but the richer humanist question ‘Where am I going?’”

Whatever else we want in our identity, we desire durability.

Is there a fundamental feature that, regardless of background, class, culture, ethnicity, political affiliation, or religious commitment, is universally desirable when it comes to identity, in addition to whatever else we may want? I think there is. Durability. Specifically, we want a robust, durable sense of self, sense of worth, and sense of action.

A durable sense of self is sturdy and does not ebb and flow with changing circumstances. Like a sea stack in the ocean, unthreatened and unmoved by the caprice of the wind and waves around it, a durable self is fixed—a firm, unchanging, genuine article of individuality under dynamic and variable conditions. Our sense of value is durable when it can be described as only loosely correlated with social approval, achievement, or adulation as well as failure, ridicule, or disappointment. “I am enough,” declares the person with a secure sense of worth. We all admire those who consistently demonstrate meaningful action—doing the right thing at the right time for the right reason—undeterred by social cost, uncertain conditions, difficulty, or the threat of failure.

Whatever else we want in our identity, we desire durability across these dimensions.

A Durable Identity: The (Continued) Need for Roots

So how do we come to apprehend and cultivate a robust sense of self, self-worth, and meaningful action? It must first be said that modernity’s inward turn to achieve self-discovery undermines the very forces that secure a durable identity. These are attributes acquired outside ourselves, not something we construct in isolation. People “weave their stable selves out of their commitments to and attachments with others,” writes David Brooks. “Their identities are forged as they fulfill their responsibilities as friends, family members, employees, neighbors and citizens.”

Brooks is speaking to an old-school way of thinking about identity, an understanding of self that is primarily defined by social roles and context. In this line of reasoning, a durable self is the opposite of an inward-to-outward movement. One particularly robust articulation of this comes from twentieth-century French mystic Simone Weil, a Christian who “belonged to a species so rare,” writes Christy Wampole, “it had only one member.”

Weil prioritized obligations over rights. Today, we extol the necessity of rights in a liberal-democratic context. Weil, however, associates rights not necessarily with social-contract arrangements but with responsibilities to one another. “A right is not effectual by itself,” she writes, “but only in relation to the obligation to which it corresponds.” In other words, rights cannot be apprehended by abstracting from our day-to-day particularities. She believes that political, economic, and social rights are meaningful when understood in relation to our contextual commitments. Western democracies can give us rights, but they cannot tell us what they are for; they must be animated by obligations. And obligations emerge from embeddedness, from a thickly webbed network of relationships, community, and tradition.

In her book The Need for Roots, Weil asks readers to imagine a country that fails to meet the material needs of a large portion of its citizenry. Naturally, we would judge this country to be dysfunctional. It does not meet the needs of its members. But, she writes, “just as we would call dysfunctional a society that fails to meet the needs of the body, equally dysfunctional is a society that fails to meet the needs of the soul.”

Intuiting our need for a more capacious definition of social progress, Weil offers a critique of societies that define human flourishing in narrow, material terms. We have a good sense of what nourishes the body, but what about our souls? She outlines a host of soul-enriching qualities such as order, responsibility, tradition, place, transcendence, freedom of opinion, and truth. For Weil, these “needs of the soul” are fostered in rootedness.

This rootedness includes language; our storied history; the associated practices of tradition, family, and kinship ties; and our sense of place. While serving the needs of the soul, these roots forge stable and durable identities. Just as the roots of a tree anchor it into the earth, absorb nutrients for growth, and protect against environmental threats, our sense of self is anchored and fortified when embedded in a mosaic of shared historical, cultural, familial, and place-based norms. Accompanying these roots are responsibilities, commitments, and moral obligations. As a colleague once put it to a group of students, “If your community does not obligate you, it is not a community.”

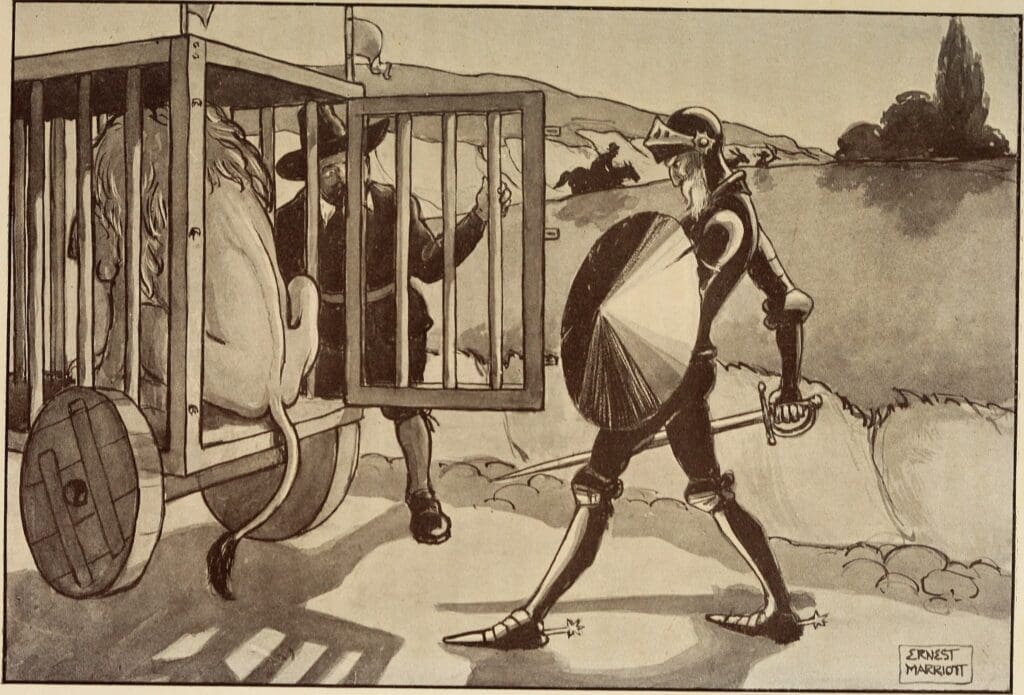

The Old Testament book of Jeremiah contrasts those who advance a self-reliant philosophy of life with those who trust in God. The former, says the prophet, are cursed. Here is how Eugene Peterson puts it in The Message: “He’s like a tumbleweed on the prairie, out of touch with the good earth. He lives rootless and aimless in a land where nothing grows” (Jeremiah 17:6). But those who seek transcendence, fostering trust in God over self, are blessed. “They’re like trees replanted in Eden, putting down roots near the rivers” (v. 8).

To use philosopher Michael Sandel’s language, these forms of rootedness are not attributes that stand apart from the self; rather, they define the self. They are, he says, “constitutive” of who we are, what he calls a “situated” self. Similarly, for Taylor, roles, goals, and ethical norms come from integrated experiences of community, not the placelessness of an isolated self. In Sources of the Self he writes, “My identity is defined by the commitments and identifications which provide the frame or horizon which I can try to determine from case to case what is good, or valuable, or what ought to be done, or what I endorse or oppose.”

Of course, not all communities, traditions, and associated practices constitute a morally exemplary self-understanding. Honour killings are also place-based, familial, and traditional. True as this is and abundant as the examples may be, the solution to unhealthy or harmful forms of community, relationship, and interdependence is not so much to uproot as it is to re-root into a better context. To uproot a person or a people would be akin to uprooting a plant and dumping it on a table—a “destruction of physical links with the past and dissolution of the community,” says Weil.

In modern North America, a variety of forces serve to disembody, atomize, and isolate us—uproot us. The forces of consumerism, digitization, social media, waning institutions, and a general dismissiveness to memory and tradition leave us unmoored. And we see the effects. So-called deaths of despair have skyrocketed in the twenty-first century. In recent years, the two characteristics most frequently expressed by men before suicide are “worthless” and “useless.” An overwhelming share of young adults describe persistent sadness or hopelessness. Modern life increasingly accommodates solitary living arrangements that erode meaningful interaction in exchange for a blanket sense of uninspired languishing. But solitude is not an inescapable affliction of modernism or a phenomenon unique to Covid, writes Derek Thompson. It is a preference that is rewiring our civic and psychic identity. “And the consequences are far-reaching—for our happiness, our communities, our politics, and even our understanding of reality.” A recent National Progress Report found that America is nearly without rival when it comes to GDP per person but woefully behind in terms of household stability, violence, inequality, fatal overdoese, depression, suicide, and anxiety. One of the authors of the report, Frederick Hess, attributes the disparity to “the weakening bonds of community and the degree to which Americans feel less rooted in close-knit bonds of faith and family.”

Being uprooted is like being on a ship without a rudder. You drift where the current takes you. A durable identity is impossible to realize in such conditions. This loss of orientation, says Taylor, contributes to an unstable sense of self. “The portrait of an agent free from all frameworks,” he writes, “rather spells for us a person in the grip of an appalling identity crisis.”

Rooted: Recapturing Place-Based Identity Formation

Early in my career, my family lived in a drafty rental property in northern Indiana. One chilly February night while my wife and I were asleep on the main floor, my five-year-old son came to the top of the stairs, moaned in pain, and projectile-vomited so violently that it cascaded down the wooden stair planks and covered the surrounding walls. My wife, who was also under the weather, has a revulsion to stomach sickness. I knew that getting out of bed meant a long and uncomfortably cold solo effort of cleaning vomit and bleaching the house.

But I did. And why did I do it? Not because I am virtuous. Not because I consumed an energy drink or some other external stimulant. Not because I could post about my actions online to curate a favourable image or garner likes. And certainly not because I felt like it.

I spent those early-morning moments attending to my son and cleaning up his stomach contents because I am a husband and a father, and that is what husbands and fathers do. It wasn’t so much a choice as a predetermined response to relational obligations that comport with being a parent and spouse. Actions, durable actions, inhere in the responsibilities associated with our socially embedded self-understanding. In many cases, there is no choice in the matter. Weil is said to have admired a reply given by a young sailor who performed an act of extraordinary bravery. When asked how he managed to do it, he responded, “Had to.”

We hold identities, but those identities hold us.

Social responsibilities are anathema to modernism’s penchant for an unencumbered self that associates liberty with a lack of restraint and an expansion of choice. “Don’t let the world tell you who you are.” But if durability is what we desire from identity, perhaps that is precisely what we should do. Our forms of embeddedness—sibling, parent, spouse, friend, congregant, colleague, member, partner, associate, teammate, and so on—limit what we can do. They challenge modern notions of freedom and moderate choices. They constrain, guide, regulate, and govern beliefs and practices.

And they obligate. Giving advice to new college presidents, a seasoned administrator once said, “In your role, there will be events you won’t want to attend. But the ‘president’ must attend them, and the president will take you with them.” Similarly, in her book The Two-Parent Privilege, economist Melissa Kearney outlines a data-driven account of disadvantages associated with children raised in non-two-parent households. “I think we need to reestablish the social convention or norm of two-parent households for kids,” Kearney said in an interview. “And [a] person pushed back on me and said, ‘Norms restrict individual freedom.’ And I think that is exactly right. And that’s the conversation we should be having. Yes, it restricts your freedom to decide you are committed to a family, to a child you raised. And even if that’s difficult, that’s what you’re going to do.” We hold identities, but those identities hold us.

Counterintuitively, these constraints are a source of freedom. In a poem to his wife, Wendell Berry writes, “What wonder have you done to me? / In binding love you set me free.” Another poet, Vera Pavlova, writes, “I am in love, hence free to live.” These voices recognize a paradox that belies modern notions of freedom and identity: liberty is associated with meaningful attachment. “The bound life is the freer one,” writes Kirsten Sanders. Perhaps the desire to liberate the self from situational commitments is not so much emancipatory as it is an act of uprootedness, making us susceptible to isolation and fragility. “A tree whose roots are almost entirely eaten away falls at the first blow,” says Weil.

My sense of self, my self-worth, and my actions are bound up in the storied framework of relational commitments, interdependence, and community. A durable self requires us to part with a self-authoring and autonomous anthropology. Identity is not discovered or created; it is established. And as we are uprooted from day-to-day relational commitments, values, and practices, not only do we lose these networks of meaning, but we lose self-intelligibility too. Like the Velveteen Rabbit, we become real through our social roles and their associated commitments.

Practically speaking, this sense of identity means nothing less than involvement. Our families. Our relational ties. Our roles as church congregants, PTO members, rotary attendees, or Little League coaches. It may mean engaged involvement in a family reunion, a game night with friends, a potluck meal, caroling at the nursing home, staying all night in the hospital room, facilitating an intervention, or cleaning up vomit late at night. And it means showing up—proximate and personal—to the humanizing contexts that bind and root our sense of self and cultivate an interconnected, interdependent life of meaning. A wedding. A funeral. A retirement party. A work promotion. A prayer gathering. A suicide call. Involvement means presence, fully inhabiting the storied spaces that have come before us and will persist long after we are gone.

This critique of the inner self as the only true self should not come at the expense of individuality—those personality traits, physical attributes, gifts, passions, and quirks that make us distinct from others. Appealing to a rooted life is not synonymous with snuffing out human particularity or collapsing differences between persons. But neither is recognizing or expressing individual characteristics the same as being rooted in enduring qualities of tradition, place, and story.

This is the paradox of identity: to forge a durable self, we must focus less on ourselves and instead commit to socially situated contexts and sense-making institutions that draw us in, name us, and obligate us. We are persons over individuals—defined not simply by internal self-understanding but by a bonded web of meaningful associations. This understanding may translate poorly to the pop-culture mantras or marketing campaigns that encourage an inward journey of self-discovery. But it does something else, something more important: a rooted life provides a realizable pathway toward a robust, durable identity. That, after all, is what we really want.