G

God’s story opens with a poem, with rhythm and repetition, and follows the God-fearers and faithful, exiles and remnants, kings and shepherds, widows and orphans, tax collectors and fishermen, centurions and Canaanites as they—we—journey toward shalom. This story of God is unfolding in the world around us, like stained glass on the streets. “The kingdom is here,” says Jesus. It’s our work to seek it.

We live this ancient story still: wandering in the deserts of unknowing, crafting idols, wanting kings, collecting too much manna; striking rocks to find our own sources when need be; resisting temptations of glory, power, and self-creation while learning and relearning the requirements of dependence, trust, mercy, and love. “If only it were as plain as a cloud by day and a pillar of fire by night,” we think.

We seek. We sit with Jesus across from the temple watching as the widow gives her two mites—all she had to live on. Jesus notices, continually drawing our attention to the hungry, thirsty, sick, imprisoned, oppressed, poor, diseased, disadvantaged, lonely, and vulnerable. He invites us to follow him across thresholds of disdain and to tables of questionable repute. We follow him into cells of solitary confinement, where prison neighbours use fishing line to pass improvised Communion wafers to one another. We follow him into bleak, blank apartments as volunteers unload beds, couches, rugs, teapots, and school supplies—making ready a home for a young family forced to flee violence, persecution, and war. “This is the first mattress my daughter has ever slept on—she’s six,” the father says.

When we see these vignettes and sense the Spirit’s sustaining hum, does not our heart burn within us as it did for sad and unsuspecting Cleopas on the road to Emmaus?

For those becoming allergic to good news or dabbling in despair, skepticism metastasizes quickly. We have too few riveting portraits of life to the full and conviction-led, justice-serious, costly self-risking. The stories that follow were written for the weary—those aching for a vision of faith fully formed, alive, and active. A fresh illumination of Jesus’s way.

Jonathan Tate

Firefighter and founder of Food on the Stove in Washington, DC.

Photos by Erica Baker

Jonathan Tate, founder of Food on the Stove.

H

“He went in the wrong building, thinking that’s where the fire was,” says Da’Von, son of the late Lieutenant McRae. “He had to run up to the ninth floor of that building, run back down the steps, go in the correct building, run all the way up to the ninth floor of that building, give commands over the radio . . .” He trails off. “I think there were two, three rescues that day. When he came back outside, he just collapsed right in front of the building. He just collapsed, and that was the end of that.”

In small towns and sprawling cities across the United States, the leading cause of death for firefighters isn’t fire or even cancer. It’s heart disease.

Firefighter Jonathan Tate is the son of a former DC fire chief who, in nine years of retirement, had three heart attacks and cancer. “He never really got to enjoy his retirement after thirty-two years on the job,” says Jonathan. “I saw the strongest man I knew go to the weakest man I knew. He couldn’t help himself off the toilet or get from the bedroom to the bathroom without being out of breath. Between him and Lieutenant McRae, it drove me to try to make an impact in health and wellness in the fire service because it’s definitely needed.”

In the fall of 2018, Tate began Food on the Stove, an intervention to save the lives of first responders. The name is a reference to food forgotten and left to burn on stovetops, which is the root cause of most calls received by the fire service, as well as a call of its own to pay more attention to the food on the stoves of the firehouses.

Jonathan Tate responding to a call.

Engine 6 honours Firefighter Da’Von McRae’s father, Lieutenant McRae.

Firefighting is the only occupation that requires employees to cook all three meals while at work. Firefighters are professional athletes, yet the kitchen culture of the fire service has yet to adopt this mindset: Food is fuel, and the cleaner the better.

When American Airlines flight 5342 collided with an Army Blackhawk helicopter at the start of 2025, snuffing out the lives of sixty-seven souls and raining wreckage into the Potomac River, Food on the Stove responded for the responders—setting up a mobile nutrition centre for the hundreds of firefighters, police, and paramedics on non-stop shift rotations in freezing conditions for weeks.

Chef Brazil Murphy prepares dinner.

Firefighting is a physically demanding job. “Food is fuel, and the cleaner the better.”

Through faithfulness to deep conviction, one visionary firefighter has woven together philanthropy, local entrepreneurs, neighbours, and other first responders to cure the heart of the fire service. “I’ve never been more optimistic about making our vision—ending heart disease in the fire service—a reality,” says Tate. “And in the process, we’ll show the world what love looks like.”

“Engine 6, respond for the call,” a dispatcher’s voice cuts in, call lights flashing and sirens screaming. “North Capitol Street and New York Avenue West. Medical local L-S response. Engine 6, respond for the call . . .”

In a snap, he and his colleagues are full tilt out the door, down the pole, in the truck, turning the wheel one more time, on their way to save a life.

Steve and Mary Park

Co-founders of Little Lights in Washington, DC.

Photos by Dave Schmidgall

Steve Park, co-founder of Little Lights.

A

As rampant violence and addiction placed Washington, DC, at the top of all the worst lists thirty years ago, Steve and Mary Park planted themselves at Potomac Gardens—a notorious public housing complex referred to by the Washington Post in 1991 as one of the city’s worst open-air cocaine and heroin markets.

Steve and Mary weren’t the first to show up, but they’re the ones who have stayed, meeting families and children in the daily realities of their needs. From after-school homework club and one-on-one tutoring to awesome summer camp and awkward middle school, the Parks raised their own two kids alongside an ever-expanding village family.

The Potomac Gardens, Washington, DC.

Little Lights centre.

Little Lights centre.

Cierra was one of them. She grew up in the Gardens and met Steve and Mary as a four-year-old in 1998. As she looks through old photos, Steve is in nearly all of them: at six as she was learning to read, at thirteen when she became a tutor, at both her high school and college graduations. All the major moments, “he’s been there.”

Sheldon had just moved into the community and was struggling as a single dad when he met the Parks. “I needed food, I needed diapers, I needed wipes. They gave it to me and didn’t want nothing for it,” he said, still incredulous nearly twenty years later. “It takes a village to raise a family—Mary raised half of the people that’s on this team. None of us are related by blood; we just related by loving God. I call it heaven.”

Cierra Peterson now leads the tutoring program.

“We learn from the people we serve,” says Steve. “We listen to their stories, learn about community, about struggle, and we’re humbled.”

Mark Andersen and Tulin Ozdeger

Co-directors of We Are Family in Washington, DC.

Photos by Steve Jeter and Jake Rutherford

Volunteers gather for delivery day. Photo by Steve Jeter.

D

Delivery days have begun the same way for more than twenty years: dressed in a black hoodie and jeans, Mark Andersen greets volunteers at a local church with an energetic pep talk about the importance of caring for neighbours. The motley crew swiftly fills bags with grocery staples before pairing off to make the rounds, each with a list of homes to visit.

“We want to build a caring community around our seniors, so they don’t feel forgotten or alone,” explains Herb Price, a We Are Family volunteer.

Mark’s wife Tulin brought operational excellence to the mostly informal process when she left her job as a lawyer and became co-director. Even through the pandemic, when the risks for seniors were at their height and loneliness at its deepest, Tulin’s planning precision ensured not a single delivery was missed.

Food must be divided before delivery. Photo by Jake Rutherford.

Volunteers pack meals into vans for delivery. Photo by Jake Rutherford.

Since 2004, We Are Family has provided monthly grocery deliveries to DC’s low-income elderly residents. Their work is based on one guiding principle: “that we see each other as sisters and brothers, and recognize that we have a responsibility to take care of each other,” Mark says.

After graduating from Johns Hopkins University, Mark nurtured his rock-and-roll aspirations as a participant in DC’s politically charged punk movement. In 1989, he stumbled onto a job at Emmaus Services for the Aging, a faith-driven safety-net organization for DC seniors.

During his ten years at Emmaus, Mark found himself at the unlikely intersection of religious ministry, punk rock activism, and black communities in DC. “I was a youth activist, but the opportunity presented itself and I grabbed it—maybe more to the point, it grabbed me—and here I am thirty-five years later,” he reflects.

Mark still speaks with visible frustration about the way DC has forgotten long-established citizens. “These are people who have accomplished truly significant things in the face of extraordinary obstacles,” he says of the senior community. Many faced legal segregation in the 1950s, witnessed riots in the aftermath of Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination in 1968, and lived through DC’s reputation as the nation’s “murder capital” in the eighties and nineties.

Photo by Jake Rutherford.

Photo by Steve Jeter.

Over the years, We Are Family’s delivery list has grown from fifty in 2004 to more than a thousand people in 2025. Easter Brown, the vice chair of We Are Family’s board, and a senior living at the Golden Rule Apartments near North Capitol Street, says those deliveries have been a crucial resource and a welcome glimmer of hope. “A lot of people lost their jobs, and a lot of people don’t have money,” she says. “But the fact that they can see some groceries every month, that’s a blessing.”

“It makes me feel so delighted to know that someone cares, that they go out of their way to care for the needy, for the hungry,” says Jacqueline Twitty, a grocery recipient and long-time DC resident, “because that is what we are to do, to look out for one another—for the destitute, for the homeless, for the sick, for those who don’t have family.”

Mary Brown

Co-founder of Life Pieces to Masterpieces.

Photos by Whitney Porter

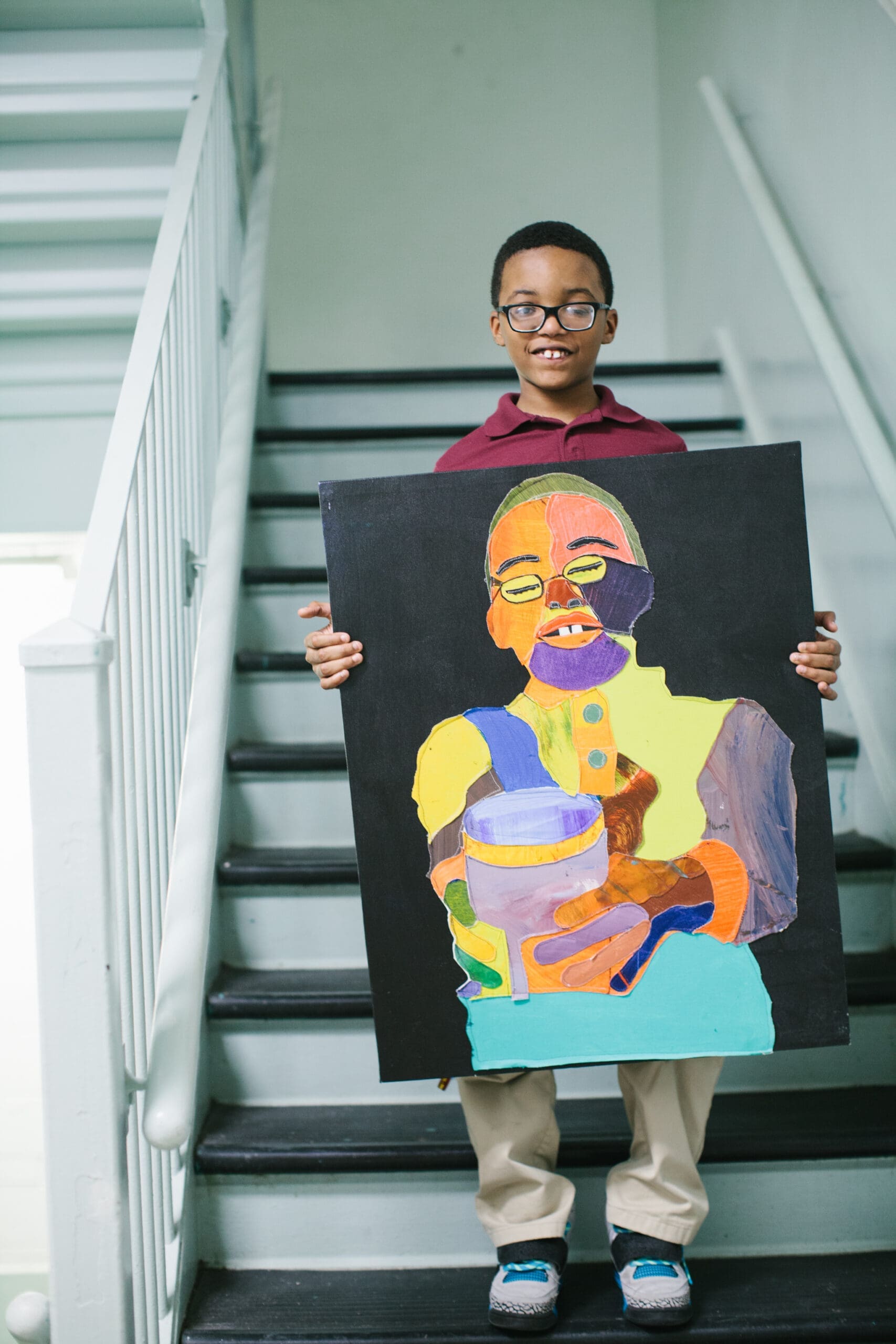

Artwork done by Life Pieces to Masterpieces participant.

T

Tory’elle Coleman was four when he first witnessed a homicide. He was playing at the park outside his home, then pop-pop-pop-pop-pop, a man running, cops in pursuit, and a body crumpled on the ground bleeding out behind them.

Street-wise, we might say, Tory’elle knows which bus stops are trouble, when, and why. He has testified on gun violence to the city council and shared his ideas for violence prevention with WMATA, the local transportation authority. He is seventeen years old and a junior at Phelps Architecture, Construction, and Engineering High School. He began attending Life Pieces to Masterpieces as a kindergartner and is now a junior mentor co-leading a class of seven- to nine-year-olds growing up in neighbourhoods like his.

Christian, a Life Pieces participant with his mentor.

Life Pieces after-school program.

“In order to be a leader you got to be a follower sometimes,” says Tory’elle, “and you got to follow the right people’s footsteps. You know, following Brother Moe’s footsteps or Barack Obama’s footsteps, that’s how you really do it.”

Brother Moe—Maurice Kie—was one of the first seven boys to join Life Pieces back in 1996, when Mary Brown and Larry Quick got it started as an art program. Seven years old, Moe lived with his mother and older brother at the top of the hill in the Lincoln Heights housing project of northeast DC.

“I would see killings. I would see people being beat up like it was nothing. Drug dealers everywhere. Someone siccing a pit bull on someone because they didn’t pay. And you still have to be a child while all this is happening, with violence all around,” says Brother Moe.

Tory’elle Coleman displays his self-portrait.

More than two thousand young men have been part of the program for some period of time, and many are still connected, still mentoring, still volunteering, still leading. Including Brother Moe.

“The main thing I always think about, it’s called ‘the purpose,’” says Cateo Hilton, a young leader alongside Tory’elle. “And it’s: Our purpose is to provide opportunities for African American males ages three to twenty-five to discover and activate their innate creative abilities to change challenges into possibilities.” For Cateo, this means consistently achieving honour roll. For Tory’elle, this has meant speaking out on issues of public safety and gun violence. For both, it means setting a positive role model for others and leading by example.

“It’s hard,” says Sister Mary. “For the older boys, it’s just heavier. The older you get, the heavier it gets, because you are fully aware of everything . . .” She trails off. Every single one of their high school students has witnessed or experienced gun violence firsthand.

“All of them have experienced the underbelly of humanity firsthand,” says Sister Mary. “I tell the boys: ‘At the end of the day, showing love and compassion will take you much further.’”

Mary Brown, co-founder of Life Pieces to Masterpieces.

Every day makes a difference. The level of intentionality required to draw the boys out of those dark moments and bleak headlines, helping them process difficult emotions and complex realities in a healthy way—well, that’s the programmatic side of the Life Pieces model. That’s their art—creating a safe space and nonviolent path, lined with support and positive role models to ensure these boys have a chance to show up fully and share their best with the world.

“Mary Brown really is black history. Every day has been the same person for the past thirty years: passionate, loving, caring, supportive. It’s unmatched,” says Brother Moe. “Everybody tell her to take a break, but she really is giving her life to supporting boys so they can have a chance.”