A

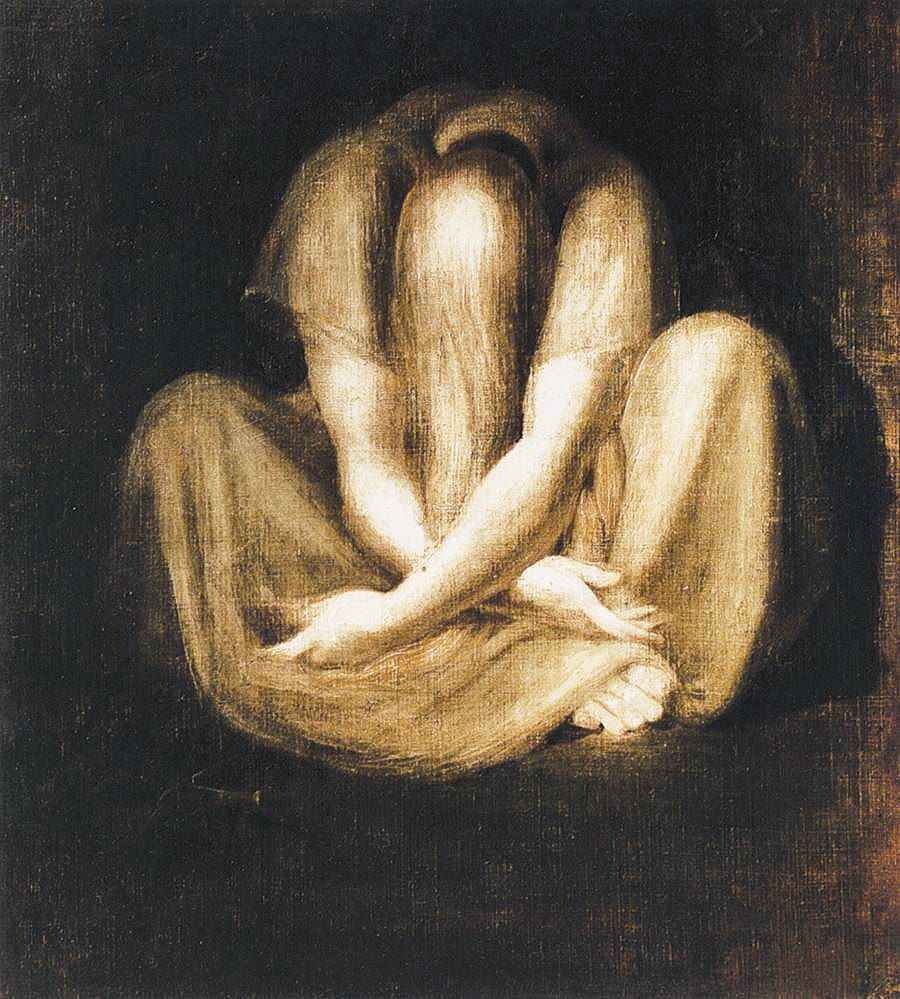

A silent retreat is like being swallowed by a whale—plucked from the direction you thought you were going, then immersed into untethered, disorienting time. Your fingers trace the gooey rib cage while dark waters slosh on the outside. Insulated and protected, you can hear muffled and softened sounds of the sea. Until unexpectedly the whale heaves and you are spit out on some distant shore.

Like other monastic orders, the Community of Grandchamp observes silence as a part of their daily practice. They describe themselves as a monastic community that “brings together sisters from different churches and various countries” for an ecumenical vocation committed to “the path of reconciliation among Christians and within the human family, and to respect the whole of creation.” Other than the Taizé prayer services sung and recited in French at the morning, noon, evening, and compline hours, the sisters carve out silence in the hours between—with an added seriousness toward the “great silence” from the end of compline at 9:00 p.m. until the morning service at 7:15 a.m. the next day. Words are permitted for instructions, meetings, and spiritual counsel; outside of these occasions, silence is tenderly held.

Monasteries have adopted silence to varying degrees over the centuries. Some take a near total vow of silence, such as the Carthusian monks; others incorporate it as a gentle disposition toward the world. St. Benedict, who wrote the first rule for monastic community in the sixth century, advised: “So important is silence that permission to speak should seldom be granted even to mature disciples, no matter how good or holy or constructive their talk.”

While silence is an ancient practice stretching back to Elijah and the desert mothers and fathers, I felt as though I were discovering something entirely novel at Grandchamp. First as a guest and then as a volunteer, I was invited into the community as an apprentice to silence.

The Community of Grandchamp emerged when a group of women were called into silence on the cusp of World War II. They began with hosting silent retreats for women in Switzerland. In 1952 the community was officially consecrated. Remarkably, they were not the only European Protestants to discover, or rediscover, silence and cloistered community at a critical juncture in the church. I became fascinated by how these pre- and postwar Protestant monastic communities facilitated healing for a devastated continent, and how silence was integral to this.

The sister who was assigned to me as my spiritual director left at my door a stack of all the books she could locate in the Grandchamp library (in English) related to my incessant questions about this relatively recent history of Protestant monasteries. As I read my way through the pile, I encountered a book written in 1962 titled Living Springs: New Religious Movements in Western Europe by Olive Wyon, a little-known, beautifully written book. Wyon gives an account for why and how these new communities had bubbled up like “fresh springs,” surfacing in the desert at a time when Christians were on the “verge of despair.”

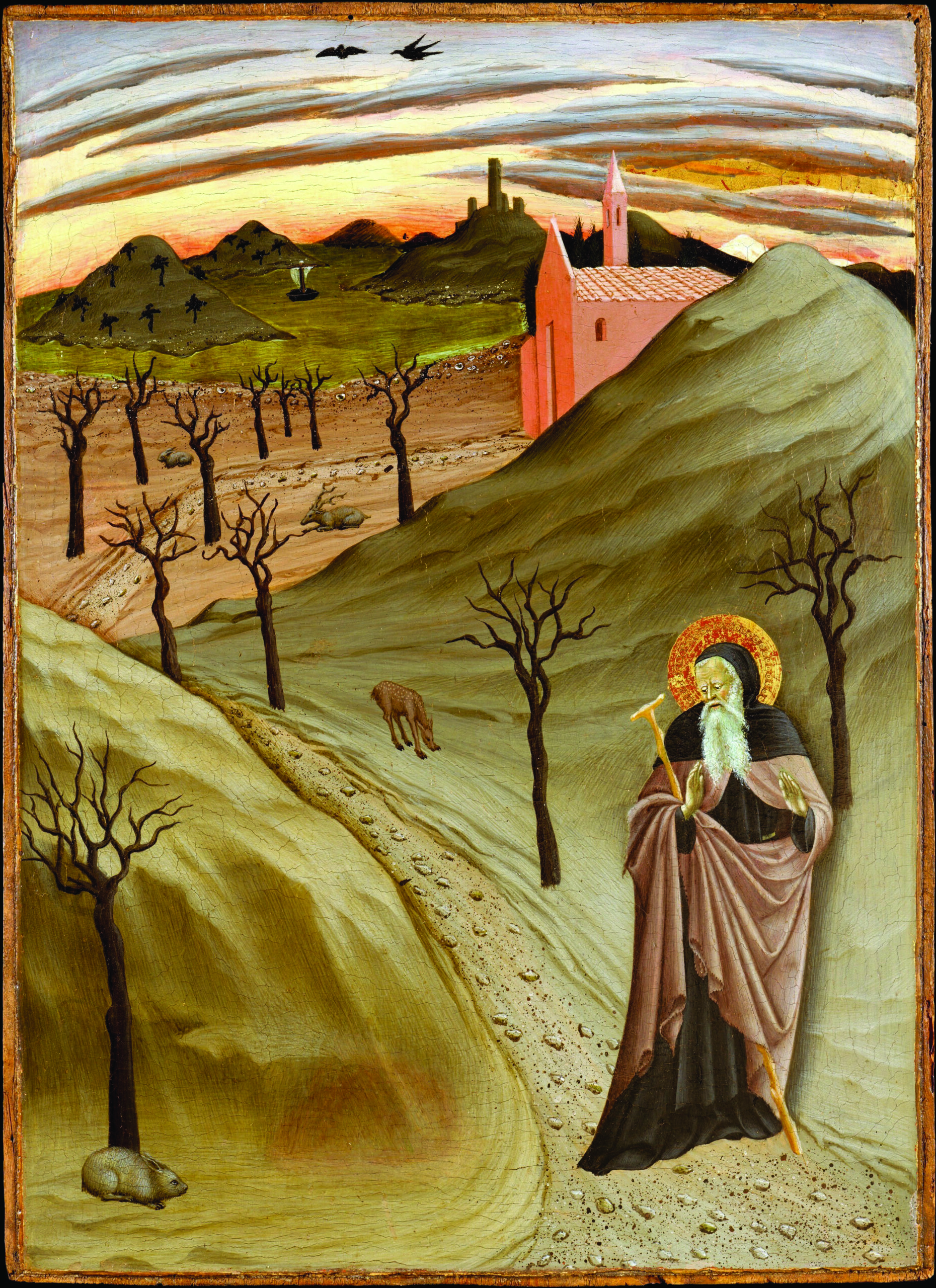

Beginning with St. Anthony of Egypt, one of the first desert fathers to journey into the literal wilderness, Wyon sketches the ebb and flow of monasticism up to the unlikely Protestant communities. After the Reformation, Protestants eschewed any practices that looked, smelled, or felt like Catholicism for several centuries, until a few Protestants in England from 1833 to 1845 started the Oxford Movement for religious and political reasons. Blending evangelicalism and Catholicism, the movement gave birth to Anglo-Catholicism and a renewed interest in historic church practices such as monastic life.

As Wyon writes, “The foundation of religious communities was the natural outcome of the [Oxford] Movement,” with the first Anglican sister since the Reformation taking a vow of poverty, chastity, and obedience in 1841. Several women’s communities then sprouted—inspired in part by Florence Nightingale. By the late 1860s it was recognized that the church needed “something new,” and at different points in history, that “something new” often took the form of creative and ordered Christian community. The Oxford Movement cracked open a monastic revival, expanding to other Protestant traditions in Switzerland, Germany, and France in the twentieth century.

There was, in the aftermath of World War II in Europe, and is, today in America, a novelty to silence and the trappings of monastic life that bubbles afresh in a world wrought with noise, disconnection, and violence.

Why were these ancient practices of silence and monasticism appearing like fresh springs? According to Wyon, it was because “‘renewal’ always comes when we return to the source, to Jesus Christ himself. But all through the course of the history of the Christian Church, this return to the source means going into ‘the desert.’ It is there, in solitude and silence, that the voice of God is heard; it is there that the river of prayer is born, that prayer which is the life-blood of the Church.”

There was, in the aftermath of World War II in Europe, and is, today in America, a novelty to silence and the trappings of monastic life that bubbles afresh in a world wrought with noise, disconnection, and violence.

What Is Silence?

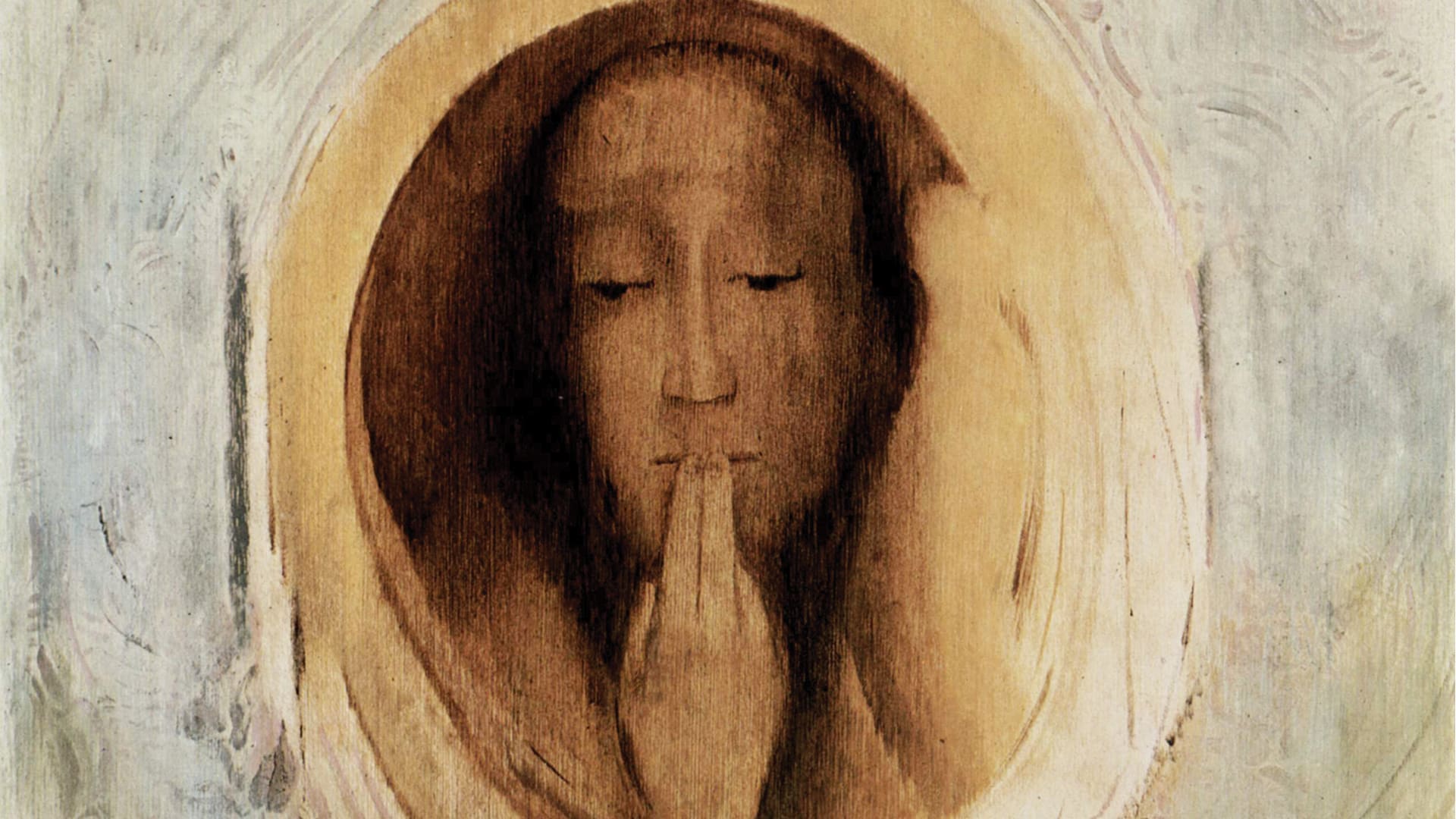

Before even getting to what silence might offer the church today, it must be asked: What is silence? To describe the ineffable nature of silence is nearly impossible, but a few themes emerged during my three-week apprenticeship.

Silence is laborious. Most guests arrive to Grandchamp tired, and if they don’t, the silence quickly tires them. Silence is heavy at first. The weight pulls down on the sinews of the neck, straining to allow the noise of distractions and the burdens shouldered to pass through one at a time. The sieve of silence clogs on occasion—a walk pats the interior clog loose. When it comes to the last interior obstruction, a blast of breath guts the rest.

Silence is a desert. The silence felt empty. I felt empty. Prayer felt empty. When I told this to my assigned spiritual mentor, she said that I arrived ready for retreat, standing on the edge of a vast and empty desert. Even though I tried to travel light, the luggage in my hands would soon become too heavy. I would have to drop the bags one by one as I journeyed through a measureless exile.

Silence eventually softens. I drank coffee in a bowl with the other guests. The first morning a few tears streamed down my face. The darkness of the room rested in wait for the sun to rise over the distant mountains. Only the sounds of those eating their breakfast and the grandfather clock were mixed in with the silence. The slow morning light met the candlelit room. Under the blanket of silence, the ring of the bell to announce prayer, or the surprise of laughter, or the song of a bird are all the same—gentle tugs, lifting the corner of the blanket to let in light and air.

What do these laborious, desert-like, and soft elements of silence provide? Silence primes individuals and communities to simultaneously experience withdrawal and revival. Deep wells, new and old, are carved out within. The slow emptying of noise and distraction fills the wells with fresh waters. This process of emptying and filling creates time and space for a tender return to oneself and to God.

Jonah’s journey—sailing through a storm, descending into the belly of a whale, and then being spat out onto a gritty shore—has felt proximate to my experiences of silence. So Jonah will be our guide as I explore what silence offers individuals and the church today.

Fear: The Storm

But the Lord hurled a great wind upon the sea, and there was a mighty tempest on the sea, so that the ship threatened to break up. (Jonah 1:4)

The sound of the storm was no mere whisper of winds. It was a “mighty tempest.” Jonah was on the run and afraid. The voice of the Lord was not heard over the roar of the sea.

The winds of our time howl, creating dervishes of distraction and fear. It is loud and disorienting. It is hard to see very far.

We are sailing through a loud, chaotic storm. As we find ourselves tossed along the waves of our time, we have to ask ourselves: What do we lose when we do not take time to be silent and still before the Lord?

The church over the last few decades has often appeared to be in competition with noise and distraction—Netflix, video games, and social media—responding to these with a flashy yet fading era of fog machines, movie sermon series, and pastoral cults of celebrity and entertainment. Church has become a produced spectacle, vying for attention. Just last year I attended a Christmas service in rural Montana with a rock band show, laser lights, and even snow-blowing machines puffing real snow onto the stage. I watched as the snowflakes melted on top of TV screens. The scene was a contrast to the silence that I imagine settled in the manger after the final cries of childbirth—humble sounds of a newborn baby suckling, animals breathing, an occasional whinny.

Predicting the effect our industries of distraction would have on our spiritual lives, Fr. Thomas Merton in 1966 reflected on the Holy Family being told there was “no room.” He writes that we live in a time of “no room,” where life is crowded out because of the “anguish” technology has caused by dominating time and space, leaving us “dazed by information [and] drugged by entertainment.” The result of this frenetic, noisy energy is that “there is no room for quiet. There is no room for solitude. There is no room for thought. There is no room for attention, for the awareness of our state.” Eventually, there is no room for ourselves, no room even for God.

The cost of leaving no room for silence is high. We are kept “ignorant of the deeper reality of God as the ground of our being,” the fruit of which is an “alienation from God, from self, from others,” writes Fr. Martin Laird, a priest in the Order of St. Augustine and author of Into the Silent Land. This alienation leads to a loss of a coherent self—an inability to make sense of who we are within a story and an estrangement from our own self. Disconnect from the ultimate story is detachment between Creator and creation.

How then do we reclaim who we are and cultivate attention to know who God is? Like Jonah, who volunteered to be cast into the deep, a plunge into the dark waters of silence is required to save the ship and its crew.

Silence: The Belly of the Whale

For you cast me into the deep,

into the heart of the seas,

and the flood surrounded me;

all your waves and your billows

passed over me. (Jonah 2:3)

In the belly of the whale, did Jonah sleep? For three days Jonah could not run from God, from himself. He was forced to rest in the unfathomable quiet of the deep, a silence and descent to a depth like death.

In our alienation from God and ourselves, how do we seek return? Laird describes the process as a “surrender” and something that cannot be “acquired” but must be “realized.” Truly, it is like dying, a “letting go and letting be” to arrive at an “awareness of God.”

While it is a position of surrender, silence is, as I mentioned, paradoxically laborious. It requires effort to rein in scattered attention, to cut back the overgrown weeds of our lives. It especially requires effort the first time—to overcome fear of the deep waters—and then the strength to jump in again and again through many storms.

Once we arrive to silence, we collect ourselves, our identity in Christ. Similar to how the Jewish rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel describes the architectural feat of Sabbath, silence is a discipline that reminds us of our “adjacency to eternity.” And when we settle into the belly of the whale, we are granted “an opportunity to mend our tattered lives; to collect rather than to dissipate time,” says Heschel.

It is there, at the bottom of the ocean in womb-like care, that we are finally able to hear. Laird explains how a moment in silence eventually arrives that reveals “we are one with God the more we become ourselves, just as we are, just as we were created to be. The Creator is outpouring love, the creation, the love outpoured.” We are reunited with ourselves and with the Creator.

Silent attention makes God’s people ready; a room inside us is prepared for the arrival of Christ.

When we are returned, something more happens in the silence. Room is made for an Advent-like disposition toward the world. In silence, the world waited in exile for the arrival of good news, stewing in a complex web of emotions of hope for redemption and lament over a broken world. Silent attention makes God’s people ready; a room inside us is prepared for the arrival of Christ. Merton writes, “Hence the Great Joy is announced, after all, in silence, loneliness and darkness, to shepherds ‘living in the fields’ or ‘living in the countryside’”; it is announced to “the remnant of the desert-dwellers, the nomads, the true Israel.” Silence as exile prepares Christians to walk in desert tracks and, like the shepherds, come to a location where we are ready to receive and share in the fullness of the good news—clearly and triumphantly.

This call is one for individuals and the church: go to silence. In this quiet darkness, individuals and the church are returned to themselves and Christ, being equipped for the desert journey and the sharing of the good news.

Transformation: A New Shore

And the Lord spoke to the fish, and it vomited Jonah out upon the dry land. (Jonah 2:10)

Jonah is spat back onto dry land. Sand embeds into his skin and the sun blinds his eyes. Jonah has been brought back to himself. He is no longer on the run from the work the Lord has called him to do. He picks himself up and walks into Nineveh.

Back on the shore, we must reckon with the sexual abuse scandals that have perforated the church, an idolatrous relationship with politics, and the rising numbers of those who have left the faith entirely. Like the church in Europe after World War II, ecumenical communities of men and women, through the practice of silence, can guide the American church to return to herself and to Christ. The former prioress of Grandchamp, Sister Minke, recounts this process in their own community with these words:

In the merciful gaze of Christ, we can lay ourselves bare in all our fragility, with our limitations, our weaknesses, our sins. And we can gradually let Christ separate us from all that is not truly ourselves, and receive from him our true image, raised from the dead with him. We must learn to die to all that is motivated by our egocentric self, our “old self” (Rom 6:6) which weighs down our actions and our relationships; a journey of purification and peacemaking when we keep silence within.

As we look to the signs of the times, this work has already begun in the United States—the sins and shortcoming of the modern church are being peeled back. A silent revival is stirring. The recent revival at Asbury University was noted as subdued and quiet-like. Anecdotally, I keep encountering individuals who have led groups of students or adults through silent retreats, incorporated intentional silence as a spiritual discipline, or expressed thirst when I began to share about my experiences with silence.

In my own life, I hold silence on most Sundays after church—it still feels laborious, but it is getting easier. I also co-led a silent retreat this year and plan to co-host two more in the coming months. But what is great about silence is that you can start as small as you need; beginning with ten minutes a day will feel like a dunk into deep waters, a momentary return to yourself and to God.

The historic practices of the church juxtapose our noisy and distracted world in such a radical and countercultural way that any impulse to “compete” with the same entertainment tactics becomes mute. It is a silent and humble revival that will water with fresh springs the deserts we have created in our lives and in the church.