T

The digital realm is fragile; it hovers like a delicate film over the stubborn, raw physicality of our material existence. This fact is easy to overlook in a world where smartphones have seamlessly integrated into nearly every part of our lives and an ever-expanding range of digital services seems perfectly tuned to anticipate and cater to each of our needs. But digital images, files, and interactions are reliant on technology and infrastructure that can easily fail, degrade, or disappear with a power outage, a server shutdown, or a corrupted file. Unlike physical objects that we can feel or even restore over time, digital content exists only as long as its supporting systems are intact and up to date. The material world reasserts its undeniable presence when the digital falters, but it’s usually not long before we’ve lost touch again, swept back up by the pull of a screen. We lose the grounding force of material reality, and we’re disembodied once more.

The temptation to escape into the comfort of our devices is hard to resist. Digital technology has played a leading role in turning comfort and convenience into two of society’s highest values. Once-arduous tasks have been simplified, and distant resources are now effortlessly within reach. The digitalization of our world has transformed our routines and interactions to such an extent that it’s difficult to fathom how we ever managed without the conveniences that now seem essential to daily life.

As it has advanced, digital technology has increasingly appropriated aesthetic experience as well, recalibrating it with an emphasis on spectacle. Iconic paintings by van Gogh, Monet, Klimt, and other famous artists have been mined to produce digitally mediated encounters that transport visitors into worlds where they can physically interact with artworks. While many of these “exhibitions” use older technologies, a surge of more sophisticated interactive events is attracting large audiences through innovative technologies like augmented reality, virtual reality, and mixed reality. This is occurring across the globe, in places like the Théâtre des Lumières in Seoul and the LUME Melbourne. Both art-centred and thematic shows like Bubble Planet or Lost Atlantis Experience are transforming commercial and industrial spaces through large-scale projections, advanced sound systems, and multi-sensory installations, enveloping visitors in vivid, animated displays accompanied by narration and synchronized to music. Some even include smells.

Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel: The Exhibition is another example of this trend, and though it’s comparatively low-tech, it operates on similar principles. Like other immersive exhibits, it offers visitors the opportunity to interact with great art of the past. The show’s producer, SEE Global Entertainment, asserts that its goal is to deliver the art experience to a wide audience in a way that’s both personal and memorable. What sets this show apart is its emphasis on visibility—seeing Michelangelo’s frescoes close-up. Forgoing visual saturation to concentrate on static details, Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel is more restrained and didactic—less immersive and entertaining—than its counterparts. Yet it’s undeniably a product of digital culture, which not only provides us with innovative media but also offers continuous opportunities to customize and enhance personal experience.

The Sistine Chapel exhibition, which has been touring internationally since 2015, brings Michelangelo’s frescoes into suburban malls and other accessible venues across dozens of cities worldwide. High-powered digital cameras were used to photograph the original paintings, and the images were transferred onto large, nylon-based canvases using the Giclée printing process. The canvases were then stretched onto panels supported by steel bars and are arranged along walls and hung from ceilings, adapted to each venue. These meticulously detailed, vividly coloured reproductions of thirty-four frescoes replicate the scale of the originals in an attempt to capture the grandeur of Michelangelo’s achievement.

Marketed as an opportunity to engage with the artwork in an up-close and personal way, the show offers the comforts of a familiar environment and modern conveniences, unlike the restrictive environment of the Vatican’s chapel in Rome. For a reasonable fee, we get unlimited time to explore, permission to take photos, the comforts of air-conditioning, relaxing background music, and the option of enjoying refreshments as we stroll. Additionally, we’re provided with educational resources via QR codes, audio guides, and text panels that explain Michelangelo’s artistic process, the historical context, and the theological significance of the images on view. Why suffer the difficulties and limitations of visiting the real thing when there’s a convenient alternative? After grabbing a soft pretzel and browsing for sales, pop in to enjoy the splendour of the High Renaissance! Located in the old Sears with ample free parking.

The iconic status of the Sistine Chapel makes it hard for us to see it for what it is, even more so in today’s digital landscape.

My first exposure to this concept was in late 2017, when an earlier version, titled Up Close: Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel, made a stop at my local Westfield mall in Los Angeles. The exhibition was on a national tour that included a prominent appearance at Westfield World Trade Center at the Oculus in New York City. Stumbling on it by chance, I found the unexpected fusion of art history with retail space, framed as an immersive experience, audacious. The show was an unexpected interloper in our local temple of commerce. But I was left cold, a common complaint levelled at immersive shows. In this particular iteration, the images were featured on multi-sided, light-filled displays, with explanatory text on strips along their edges. As with the current version, audio guides supplemented the show. But aside from the scale and lighting, which were strangely reminiscent of transit-shelter ads, I didn’t find the experience qualitatively different from browsing through a coffee-table art book at a Barnes and Noble.

Yet I enjoyed seeing the images at scale, and there’s no question that these shows offer something of value to those who haven’t been to—or can’t get to—the Sistine Chapel itself. The cost of access, however, is the recontextualization of the work as commodified experience. And the promotional hype and commercial mediation divert attention from what actually gives Michelangelo’s frescoes their enduring power.

Ironically, the iconic status of the Sistine Chapel makes it hard for us to see it for what it is, even more so in today’s digital landscape. We rarely grasp the whole, as the ceiling is often reduced to a series of isolated, conveniently accessible images in art history books, websites, and commercial reproductions. However, experiencing the real thing in its original context offers anything but comfort.

First, there’s the often-commented-on physical difficulty of viewing the ceiling itself. Covering a vast space over sixty feet high, viewers must crane their necks and, often, experience visual fatigue from looking upward for extended periods. Add to this Michelangelo’s use of complex perspectives and foreshortening, which can create visual distortions, making it hard to interpret the figures and their spatial relationships correctly from different angles. The natural lighting in the chapel can vary, sometimes casting shadows or creating glare, complicating the viewing experience. And, as the Sistine Chapel is one of the most visited sites in the world, the sheer number of tourists can make it difficult to find a good vantage point or to concentrate on what’s above you for long.

Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel: The Exhibition purports to provide a remedy. The convenient availability of true-to-life-scale digital representations means a comfortable and controlled experience, allowing us to explore Michelangelo’s masterpiece despite our physical remove. This allows us to learn a little about Renaissance art and expand our cultural knowledge more generally.

Don’t get me wrong. Digital reproductions are incredibly valuable, especially when they fuel the pursuit of learning. But it’s important to acknowledge their limitations and supplement them adequately with further study. I get a thrill out of the virtual tour of the Sistine Chapel on the website of the Vatican Museums, which allows for a 360-degree, high-resolution walk-through of the entire space. But the compositional design and its content remain a puzzle unless you delve into the complexities of art and religious history, including the chapel’s purpose as the site of the principal papal ceremonies and the place where the Sacred College of Cardinals elects popes.

Encountering the actual frescoes on site does something more. It prompts us to consider how our beliefs about our own place in the divine plan are formed.

Encountering the actual frescoes on site does something more. It prompts us to consider how our beliefs about our own place in the divine plan are formed. Standing beneath Michelangelo’s ceiling, awe leads to an awareness of the profound role of images in shaping our concepts of God, the stories of the Hebrew Bible, and the vision of Christ’s return on judgment day.

This is what happens through the phenomenology of authentic engagement with an artwork, in the sensory and experiential aspects of a direct encounter.

Here, it begins with a sense of place. Michelangelo’s frescoes are designed to harmonize with the chapel’s architecture. Since he embedded his figures within painted architectural features that appear strikingly real, it’s difficult to discern where the actual roof ends and the artwork begins. The overwhelming presence of the imagery within the spatial and structural features of the chapel is one way visitors are drawn into absorption. Furthermore, Michelangelo’s ceiling, featuring scenes from the Old Testament, and his altarpiece, depicting the last judgment, exist within a larger scheme of paintings. The contrast between his work and that of the other Renaissance masters, including Botticelli, Ghirlandaio, Perugino, and Signorelli, which cover the northern and southern walls—devoted to the lives of Jesus and Moses, respectively—highlights the varied artistic interpretations of biblical themes within the Catholic tradition. This larger context prompts us to reflect on the complex relationship between art and theology.

Within the sacred context of the Vatican—the heart of Catholic worship and authority—the Sistine Chapel melds these artistic and religious elements, deriving power from both to create an environment where the physical presence of the artwork invites contemplation in the midst of profound aesthetic experience. This form of immersion, in contrast to the commercial type, encourages us to consider the eternal themes Michelangelo explores, such as divine perfection, existential longing, and the human condition, making the site-specific experience a uniquely powerful and transformative engagement with faith through images.

Digitizing the Sistine Chapel frescoes seems to allow broad access, but to what? A simulation doesn’t preserve the actual work; it disseminates surface effects. While the original space challenges us physically and perceptually to alter our viewing habits, its reproductions are packaged for easy consumption. The unique experience of the original is traded in for innumerable copies that endlessly circulate in our media ecosystem. These images are ephemeral and lack the presence—and thus timelessness—that only the physical frescoes in real space can convey. With the loss of original context comes the loss of deeper meaning, as the images become floating signifiers to be appropriated for commercial ends or turned into memes.

Specificity and a sense of place serve to remind us that every religious artwork (indeed all art) is an interpretation that reflects its cultural context, its historical period, and the power dynamics that led to its creation. (Here we might recall Michelangelo’s tensions with Pope Julius II.) While striving to depict eternal truths, Renaissance artists were influenced by the specific interpretive framework they internalized in their own time and place. As Jacques Maritain aptly states in his classic text Art and Scholasticism,

Art does not reside in an angelic mind; it resides in a soul which animates a living body, and which, by the natural necessity in which it finds itself of learning, and progressing little by little and with the assistance of others, makes the rational animal a naturally social animal. Art is therefore basically dependent upon everything which the human community, spiritual tradition and history transmit to the body and mind of man. By its human subject and its human roots, art belongs to a time and a country. That is why the most universal and the most human works are those which bear most openly the mark of their country.

Understanding Michelangelo’s work must begin within the context of the Holy Roman Empire immediately before and after the Protestant Reformation.

For the viewer as well, reception of the image and its influence on one’s understanding of the divine is contingent on ever-shifting cultural and historical perspectives. After all, we can only process what our conceptual framework can handle. But while we are limited by the conceptual frameworks we adopt or inherit, always seeing only part of the whole, the Sistine Chapel overflows with meaning. It stands as a testament to human ingenuity and creative interpretation, and experiencing it in its fullness can inspire renewed enthusiasm for Scripture. And despite what we contemporary viewers may regard as idiosyncrasies in Michelangelo’s vision of Genesis, the prophets, and the last judgment, his frescoes succeed in gesturing to the transcendent. Much of their impact, in other words, stems from a profound otherness that’s foreign to both secular culture and mainstream Christianity.

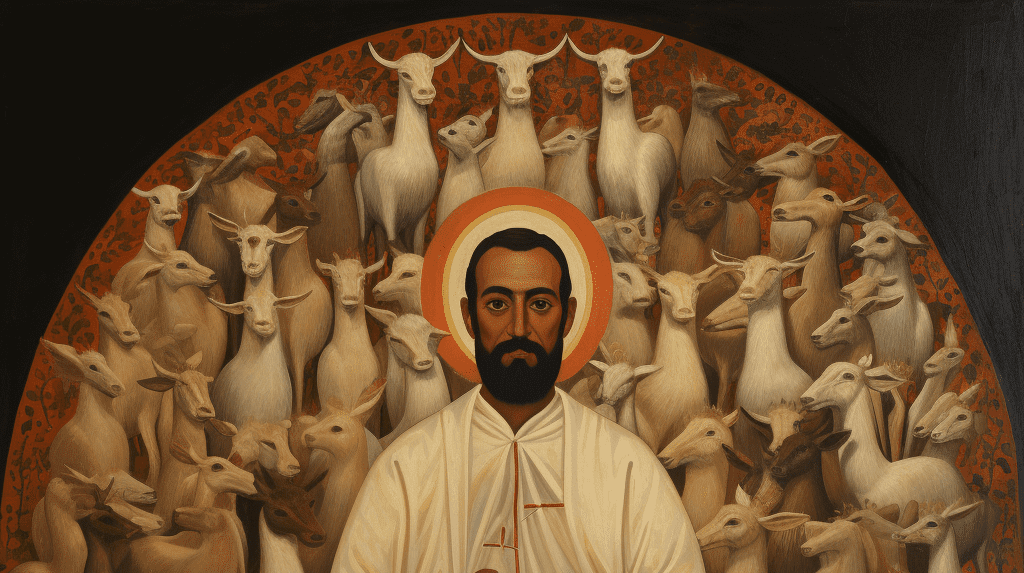

Michelangelo’s figures defy conventional norms. Take Christ’s beardless face in the Last Judgment. It clashes with centuries of established religious imagery, making him appear more like an idealized Roman emperor than a figure of humble sacrifice. This charged, massive body with its undersized head disrupts familiar notions of divinity and sacredness, presenting instead a vision of Christianity that resists easy categorization and conventional understanding. Michelangelo’s bodies, with all their androgyny, bulk, and exaggeration, seem almost alien to us. They possess a strange blend of power and elegance that makes them feel as if they belong to a different realm, one that both fascinates and troubles us with its atmosphere of intense, transcendent energy.

Michelangelo’s figures seem to strain against the boundaries of their earthly existence, as if their very musculature is an expression of the soul’s longing for union with God.

Michelangelo’s personas also shift the focus of identity from self-perception to divine perception. In our society the construction of identity often revolves around concerns with self-image and social approval. This can lead to a kind of self-idolatry, where the body becomes an object of constant scrutiny, which we attempt to mold in pursuit of an idealized version of ourselves. Michelangelo’s figures suggest a different source of identity, one that’s found not in the mirror or in the gaze of others but in the eyes of God. They symbolize the divine force that enlivens the world, but also the perfection we seek as we grapple with the weight of our mortal state. Michelangelo’s figures seem to strain against the boundaries of their earthly existence, as if their very musculature is an expression of the soul’s longing for union with God. Their energy is directed not toward self-aggrandizement or the pursuit of earthly perfection but toward transcending the limitations of the human condition.

Thus, the physical power of Michelangelo’s men and women becomes a symbol of the divine potential within each of us. These figures represent not just physical strength but a spiritual vigour—a latent power within the human form that can be fully realized only in communion with God and the energy that animates all of creation. His heroes, prophets, sibyls, and ignudi signify that true identity—in its universality, in its holy state that transcends male and female aspects—is not something we construct for ourselves but something we discover through our relationship with God.

Michelangelo’s figures can also be seen as reflective of our potential for divine transformation, for the overcoming of the flawed, temporary state of our flesh. In the divine gaze, we are seen as our fullest, most glorious selves—as selves that transcend the limitations of time and participate in an eternal reality. This divine perspective challenges us to see ourselves not as isolated individuals striving for perfection in the eyes of the world but as beings whose true worth is found in our connection to something greater. In this way, Michelangelo’s work becomes not just a portrayal of the human form but a profound meditation on the nature of human identity and its ultimate source in God.

In his writings, the philosopher William Desmond discusses the concept of the “overdeterminate,” particularly in relation to works of art. He explains that a work of art is unique and rich with meaning, offering an inexhaustible depth that no finite analysis can fully capture. While art historians can analyze and interpret the attributes of Michelangelo’s ceiling and altar wall, no analysis can definitively exhaust its meaning. As a unified whole, it manifests a surplus of meaning. Contrary to the imprint left on a viewer’s mind after seeing the Sistine Chapel show, Michelangelo’s figures do not constitute isolated moments. They form an interconnected vision of divine creation. The ceiling and altar wall pulse with an intensity we cannot fully comprehend, confronting us with the mystery of existence. Each form, each scene contributes to a larger narrative that reflects the excess of God’s creative power—a power that flows outward, taking us with it. Entering the chapel, we’re challenged to embrace the inexhaustible richness of the sacred.

The images must be understood as a totality, because as they transmit the abundant outpouring of God’s spirit through their excess, they also immerse us in the human drama. Michelangelo’s transformative vision draws together time and space, heaven and earth. His figures act and commune as a group, inviting us into a radical Christian perspective where the body becomes the site of deep interrelatedness and participation.

Why wouldn’t these images challenge us? Their sense of otherness stems from a view of the human condition that we have largely forgotten.

Art and entertainment can both evoke powerful responses. Yet they establish different relationships with their audiences. Great art challenges and stimulates through its complexity and the depth of its message. Entertainment is meant to be more immediately gratifying and less demanding. Where art plays with ambiguity, pushes boundaries, confronts difficult truths, questions assumptions, and leaves us unsettled, entertainment tends to soothe, providing comfort, escape, and predictable resolutions that reinforce existing beliefs. While art engages our intellect, entertainment aims for temporary diversion. Of course, art and entertainment are not always this distinct. Many popular films and music incorporate complex themes or produce a strong emotional charge. And art can also provide elements of entertainment through its craftsmanship, beauty, and emotional resonance. The boundaries between the two are fluid, and their overlap is often what makes a cultural product widely admired.

But the Sistine Chapel exhibition currently touring shopping malls across the nation erases distinctions between art and entertainment by packaging aesthetic experience as a commodity. Just as digital media blurs the lines between high art and popular culture—placing a symphony and a streaming TV series in the same competitive space or showing an opera in a multiplex—this show fragments Michelangelo’s overwhelming achievement into easily accessible digital reproductions disconnected from any sense of place. In doing so, it subordinates the artwork’s complexity to the logic of convenience and spectacle. This shift feeds our desire for self-fulfillment, providing a sense of having “experienced” art without the deeper, demanding engagement the original works invite. While art traditionally challenges us to reach beyond ourselves, the Sistine Chapel show domesticates Michelangelo’s work for easy consumption, aligning with the priorities of digital consumerism and seductive product design. It turns what for many is a pilgrimage to a sacred site into an accessible, repeatable, and purchasable experience, catering to consumer desires for instant gratification.

The shift toward spectacle centres the viewer’s experience and desire for entertainment in contrast to the original intent of the art. The frescoes, originally meant to evoke awe and spiritual reflection, become objects of visual pleasure, allowing viewers to consume a diluted version of the sacred without personal or spiritual investment. This reinforces a culture where the self, rather than God, is placed at the centre of the experience, diminishing the meditative and reverential purpose of the original works.

Of course, getting to Rome isn’t easy. I’m grateful for the unforgettable experience I had visiting the chapel as a young man. But even if one can’t manage the trip, there’s always books and articles, documentaries, lectures, courses, and the aforementioned virtual tour, accessible to a worldwide public thanks again to digital technology.

When it becomes clearer to us that exhibitions like Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel are consumer-driven, we can appreciate all the more how true art challenges us to abandon our desires and consider what it’s offering instead. With the real Sistine Chapel, it’s an otherness that reawakens us to wonder as it teaches the importance of creative interpretation in the revelation of spiritual truths.