—Deuteronomy 7:13

P

“Phoebe,” my voice breaks into two staccato syllables. Cut in two phonetic slices of the same name: “Phoe-be.” Cut from a womb that could no longer hold her.

“Her name is Phoebe,” I hear my husband Josh’s voice carry the chorus. I imagine my voice lost in his. Had I ever heard it beyond the screaming in my mind? Perhaps it had dropped off. Or perhaps it was never there. Or perhaps it was there the whole time. In the polyphony: the metallic chords of surgical instruments, the syncopated beeping of a pulse/ox monitor set up to a rhythm of its own purposes, the oddly chipper tenor of an ensemble of residents, vocalizing “NICU,” “two pounds,” “premature.” A surreal round where no boat rows gently down that good stream.

I strain to hear the climactic note of this sterilized, necessary choir singing my daughter into the world, into this room, into a plexiglass box that would be her world for the next six weeks.

A plexiglass box, 2021’s biomedical substitute for the womb. The box could hold my child better than the circle of flesh of my own body. And yet.

For the box, I am grateful. Grateful for the paradox of neoliberalism’s technocratic fruits, which are bitter substitutes that yet save life in those emergencies when Mother Nature’s course is deadly. As it would have been for both of us.

Waiting to hear my daughter’s cry, I remember the miscarriage. I have seen early pregnancy end in the womb. My womb—hesitant to contract and release the tiny flesh and blood of a developing human. Holding on to her, clinging to her. My innards encircling her in the maternal love of my innermost being. For she will not be born into the womb of this world, but into the womb of God.

Finally, the note I have been straining to hear. Was she breathing? Whose cue was it? The surgeon? The nurses? The residents? My husband? Who will say the words that will confirm her life, her breath?

Womb-full Music

Then she does. Phoebe. She sings herself into the world. Not the mechanical, contrived polyphony of beep and scrape that had released her from my womb. Her song is monophonic, filling the room with her breath. Her ruah. Her wind. Her spirit.

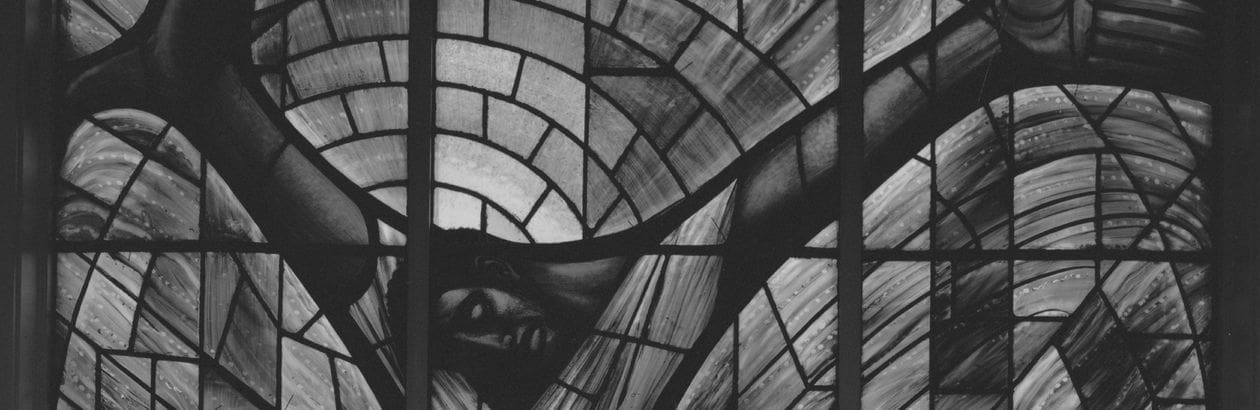

My mind drifts to Hildegard von Bingen, the twelfth-century mystic, polymath, visionary, composer, healer, saint. Her monophonic chants reverberating off stone-vaulted abbeys. It was not merely von Bingen who produced the otherworldly music. It was the interplay, the interdependence, the co-creational lovemaking between the human individual and the stone sanctuary womb that held her, soma and song. Von Bingen, born one thousand years after the New Testament’s Phoebe and almost one thousand years before our monophonic daughter, her memory enchanted the antiseptic operating room with the soundscape and imagery I needed to make sense of the unspeakable mystery of co-creation between my womb and my daughter.

What if there was a different way of viewing the ordering of life?

Wombs are not tiny boxes, not a static, staccato cube. They are not made of Malvina Reynolds’s ticky-tacky; they are not all the same. They are not made by man, for man, but by God, for God. A circle. A sphere. A cosmic egg. Von Bingen’s Responsory for the Virgin goes, “[The Virgin] whose womb / divinity most holy with / its warmth has flooded so / a flower has sprung within it. / . . . And so the sweet and tender shoot— / Her son— / Has through her womb’s enclosure / Opened paradise.” And in Hymn to the Virgin, von Bingen lyricizes, “Your womb rejoiced as from you sounded forth the whole celestial symphony.”

Von Bingen understood that the womb was not an inanimate vessel. No, the womb is alive and vivifies our spiritual imaginations toward the very essence of God—a co-creative being whose name is Love. Whose character is compassion.

Phoebe. From my living flesh she came. From the womb of God she came. With her own womb—where the cells that could one day become my granddaughters live—she came.

Phoebe. Radiant One. From Old.

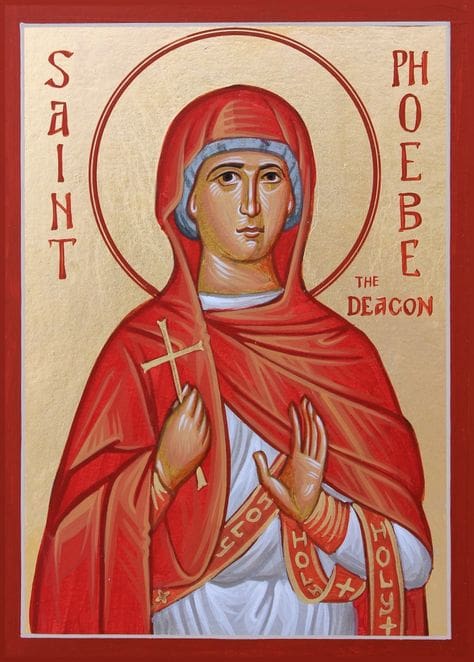

Your mother named you after the biblical Phoebe of first-century Mediterranean society. The sister, the patron, the diakonos, the emissary of Paul—a spiritual mother in the early movement of Christ followers.

Your father named you after Phoebe, a first-generation titaness of Greek mythology. Daughter of Gaia and Uranus. Grandmother of Apollo and Artemis. Arguably, a spiritual mother of the pantheon. A spiritual grandmother to lunar goddesses like Diana.

You hold both within you. Within your innermost being. Within your own womb. Spiritual mother of early Christianity and spiritual grandmother of elemental goddesses.

Daughters of the Flesh, Mothers of the Spirit

The premature birth of Phoebe in the summer of 2021 offered another paradox whose power we still contemplate.

The inadequacies of my physical womb had opened me both to deep shame and to deep curiosity. My womb, in terms of its productivity, had failed. It had not proved itself to be a safe and compassionate place for my still-developing child.

But something less visible begged to differ. Had it failed? Was the telos of a womb only the measurable quantifiability of its physical fruits? What happens when physical wombs fail, remain barren, birth children already born to heaven, birth children who fail to thrive, cease menstruating, grow tumours? Were wombs to be measured by what and how much they produced?

“I totally reject the idea that you are not a mother unless you have children of your own,” wrote Catholic philosopher Alice von Hildebrand. “Motherhood is not only biological maternity. It is spiritual maternity. . . . Pray to God that he sends you spiritual children.”

Wombing History

What does it mean to understand the spiritual essence of the womb, not merely at the functional level, but at the soul-being level?

Sister Margaret is a Japanese American nun who has committed the last forty years of her life to serving Christ in a small community of women religious outside Baltimore, where we live. Sometimes her nurturing processes seem needlessly delayed; as we volunteered to cut the precious milkweed from her garden this past summer, it often seemed like we were gathering more weeds than milk. Through the patient caregiving she offers to every created thing—from monarch butterfly to plant tendril to my curly tendrilled two-year-old—life blooms into its intended plenitude. She often hums to us about the milkweed feeding the butterflies, the butterflies feeding our souls—a circle of loving-kindness, that interdependent “with-ness” of being held in the maternal matrix. Not unlike Joshua encircling Jericho seven times before the walls came tumbling down, the circling activity, which is the womb’s way, does not pin down, but submits to the cyclical nature of life.

What if the cosmos consisted not of linear timelines nor of hierarchical pyramids ascribing value to different life forms, but of humans participating in the dance of collaborating spheres?

Western democracies are sloughing through the twilight of movement-building strategies built primarily from masculine emphases on quantification and scale, visibility and punchlines. Such impulses should not be cancelled. But it is worth opening our eyes to the role that spiritual mothers also play in nurturing the seedbeds of social change—gestations of relationship and wrestling that patiently nurture the quiet before.

Her silver visage in the wat’ry glass

Decking with liquid pearl the bladed grass.

—William Shakespeare, A Midsummer Night’s Dream

We were aware of our daughter’s namesake intwined in Christian and Hellenistic encounter. The apostle Paul recommended the highly esteemed Phoebe of Kenchreai to a group of early disciples in Rome: “I commend to you our sister Phoebe, a deacon of the church in Kenchreai. I ask you to receive her in the Lord in a way worthy of his people and to give her any help she may need from you, for she has been the benefactor of many people, including me.” But it was the cast-aside line in Shakespeare, with its lunar reflections, that awakened a fascination to know more.

Joan Campbell’s Phoebe: Patron and Emissary illuminates how, in first-century Mediterranean society, Phoebe’s designation as a “sister” among non-related individuals suggests that they embraced her in the fullness of familial human dignity. These early Jesus groups formed fictive families that sought to embody loving-kindness to one another, as image bearers of the divine. Through her spiritual maternity, Phoebe played an innovative role in shaping an emerging, relationally based social institution, the early church, as both a diakonos and as a patron. Phoebe’s societal values and perceptions would likely have been deeply rooted in the physical landscape of Kenchreai—both the human social structures and the natural environment. Kenchreai, surrounded by arid barrenness, was known as a location of relative fertility and abundance of fresh water and of crops. In antiquity, it housed an icon of Artemis, a sacred site dedicated to Isis, and a temple to Aphrodite. The presence of these pre-Christian deities seems particularly synchronous given that the biblical Phoebe could well have been named after the Hellenic titaness Phoebe, spiritual grandmother to a plurality of elemental deities.

—Mother Elizabeth Ann Seton

It was the witness trees, the ash in particular—known through folklore to be protectors of newborn babies—that called us to her. In COVID-time, mothers of younglings desperate enough to leave the house gained superhuman powers scouring event boards to find outdoor, family-friendly activities. So it was to the shrine of the first American-born saint and foundress of Catholic schools in the US, Elizabeth Seton, that we headed to see the ash trees that serve as the last living witnesses to Seton’s life and guardians of the spiritual seeds she planted.

Mother Seton converted to Catholicism as a young, widowed mother and founded the first US order of Catholic women religious, the Sisters of Charity, as well as schools and social-service organizations. As Seton was cultivating the Sisters of Charity and a school in rural Maryland, both her family and Catholic leaders challenged her with how she would balance her duties to her five young children with her growing responsibilities to her spiritual children. Seton developed a creative new model, drawing from the Ursuline tradition, where religious sisters would only make vows for one year at a time. The un-avowed were permitted to live with the community as boarders. Seton’s maternal instincts led to an innovative community of spiritual sisterhood in which women committed themselves to service for one-year intervals, much like a faith-inspired AmeriCorps, almost two hundred years before its inception. Seton saw the beauty and provision of her Creator through his natural creation on St. Mary’s Mountain and in St. Joseph’s Valley (the names Seton called the surrounding area). Seton sought to pass on her eco-spirituality to her daughter Anna Maria, gifting her a copybook filled with Seton’s poetry. Seton wrote to her daughter, “Those even that examine the beautiful order of creation are suited to fill the mind that is making acquaintance with their great Author. . . . I must leave it to You to finish what I have begun.”

—Harriet Tubman

While walking a little-trod trail, a mitten-shaped leaf. Mitten-shaped like my motherland, Michigan. Waxy verdancy. A question. An answer. Sassafras.

I was taking a course that was just a smidge too woo for me. I was supposed to open myself to cultivating a new relationship with a non-human life form that was presenting itself to me. “Woo,” I sarcastically uttered to myself, rolling my eyes. And yet. Sassafras.

A quick Google search led to an NPR article on how Harriet Tubman partnered with sassafras’s roots and many other elements of the natural world throughout her life. Tubman cultivated sassafras as a medicine and supported herself by selling root beer made from it, along with fresh baked pies. Born on Maryland’s Eastern Shore and known as a mother on the Underground Railroad, in 2022, people around the world are celebrating two hundred years since Harriet Tubman’s birth. She was enslaved for twenty-seven years before self-liberating to Philadelphia. She travelled back to the South many times in the forthcoming years, eventually helping over seventy people—many her own kin—safely self-liberate to the Northern states and Canada.

In midwifing the journey from bondage to freedom, Tubman partnered with the natural landscape of Maryland’s Eastern Shore. She learned to navigate by the night stars, to imitate the sound of a barred owl, to forage sassafras roots as medicine, and to traverse the intricate waterways that eventually led to freedom. In Harriet Tubman, Moses of Her People, Tubman’s friend Sarah Hopkins Bradford emphasizes Tubman’s intimate companionship with her Creator. Bradford writes, “She seemed ever to feel the Divine Presence near, and she talked with God ‘as a man talketh with his friend.’” Later in her life, Tubman shifted her efforts from leading her people to freedom to cultivating the social and humanitarian institutions necessary to care for those freed persons. Tubman was a spiritual mother even to her own elderly parents, who served as inspiration for her founding of a charitable home for aging African Americans to prepare for their final journey into the hands of their Creator.

Over time, the great spirit of the land felt [Mother Bear’s] sadness, recognizing her dedication and love for her children. With a tremendous gust of wind, the spirit brought the cubs near shore, raising them out of the water as two magnificent lands, placing them forever within the watching and caring eyes of Mother Bear.

—Kathy-jo Wargin, The Legend of Sleeping Bear

Leelanau. Land of the Sleeping Bear Dunes. Land of my childhood summer vacations. Upper left of the Michigan mitten. I knew the earth, the big lake, the sandy slopes by name: Leelanau. And yet, not until rereading a children’s book about Sleeping Bear Dunes after Phoebe’s birth did I ask the question that would lead me to Jane Johnston Schoolcraft: Who was she? Leelanau?

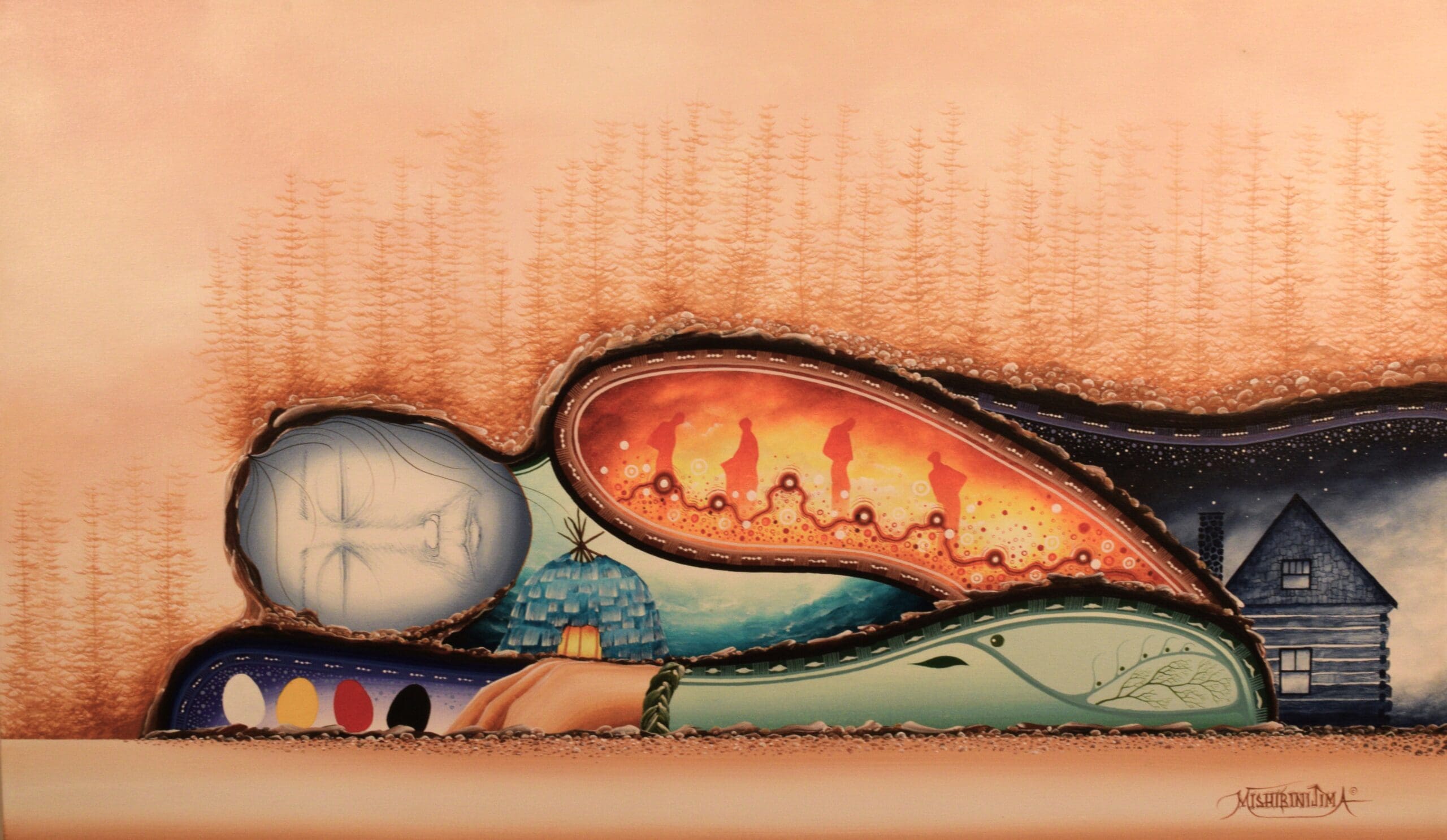

Jane Johnston Schoolcraft (her English name), or Bamewawagezhikaquay (her Ojibwe name), or Leelinau (sic) (her pen name), was born in 1800 in Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan. Jane, or Woman of the Sound the Stars Make Rushing Through the Sky, is considered to be the first Native American literary writer and poet. She wrote at least fifty poems, ten songs, and eight oral Ojibwe folktales. Her work served as source material for Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s Song of Hiawatha. Schoolcraft seeded an awakening to Native American culture and literature that still has not yet received its full due. Not until 2007 were her complete works published, in an edited volume by Robert Dale Parker.

In A Psalm, for mercy, and confession of Sin, addressed to the Author of Life, in the Ojibwa-Algonquin tongue, Schoolcraft addresses God as “Merciful spirit, great author of life, abiding above, / Thou hast made, all that is made.” Ojibwe folklore and spiritual stories shared by her mother and the luminous characters of Shakespeare and other English literature, pulled from her Irish father’s library, filled Schoolcraft’s childhood imagination. She also proved an invaluable partner to her husband, explorer and cultural anthropologist William Rowe Schoolcraft, whose fame has regrettably eclipsed his wife’s. Together they produced the Literary Voyager, a journal of the first written Native American poetry, songs, and folktales. Parker notes the underlying maternal values of the Ojibwe, even in their approach to trade: “When they traded or negotiated treaties to get rum, they described the rum as ‘milk,’ hence connecting it to the maternal.” The primary social institutions Schoolcraft participated in during her lifetime—home education, faith community, fur-trade networks, even the founding of a literary journal—were porous in their boundaries between each other and fluid in their (mostly) mutually supporting roles. Family connections bound them all together.

Schoolcraft demonstrated her intimate connection with God in the landscapes of her youth. In her poem “Lines Written at Castle Island, Lake Superior,” Schoolcraft explicitly references her motherland as a sanctuary against encroachment of Western civilization: “Here in my native inland sea / from pain and sickness would I flee / . . . Lone island of the saltless sea! / How wide, how sweet, how fresh and free / . . . Ah nature! Here forever sway / . . . No pride of wealth; the heart to fill, / No laws to treat my people ill.” On the theme of her homeland, in “Lines Written Under Affliction,” Schoolcraft writes, “Or, how could a beautiful landscape please, / If it showed us no feature but light? / ’Tis the dark shades alone that give pleasure and ease, / ’Tis the union of sombre and bright.” Schoolcraft, who was often ill in her young adulthood, saw in the craggy, wave-battered coastlines of northern Michigan the interplay of dark and light, suffering and pleasure, that cultivated an organic, animate connection to God.

Building and Being

The word that the Pentateuch first uses for compassion is rakhum, closely knit to rekhem, the Hebrew word for womb: “And he passed in front of Moses, proclaiming, ‘The Lord, the Lord, the compassionate and gracious God, slow to anger, abounding in love and faithfulness, maintaining love to thousands, and forgiving wickedness, rebellion and sin” (Exodus 34:6–7).

The womb-full compassion of the Hebrew Bible ties directly to mother and child, but need not be exclusively gendered. Scripture describes men as having their wombs moved. In Genesis, when Joseph first sees his beloved youngest brother, Benjamin, he is moved in his inner-space (43:30). Although many translations say “bowels,” womb is arguably a more accurate translation. The word is rachamim, translated as something like “maternal care” or “tender loving kindness.” From our vantage point, translating this word as “bowels” does not quite capture the essence of this passage. Wombing just might. Wombing is how God gestates his people and holds them. How God moves us to compassion for others.

Ignoring the force of spiritual mothering in the world leads to distorted images of God that perpetuate dehumanizing cosmologies, materially reductionist ideologies, violent philosophies, and totalizing political worldviews. When we only associate the image of God with biologically male bodies, then women become less than image bearers and somehow less than human. And when we only associate the gifts of God with traditionally male vocations, we degrade the very image of God reflected through women. These animating beliefs birth societies that eliminate the role of spiritual motherhood. They offer women no opportunities to lead with compassion and nurture.

Phoebe, Elizabeth Seton, Harriet Tubman, and Jane Johnston Schoolcraft all served as spiritual mothers—nurturing the relational root systems of emerging social movements—the early church, abolition, education for girls, and a Native American literary cultural awakening. Many of these social movements emerged, strengthened, and even peaked within these women’s lifetimes, before starting the cycle anew to include even more people.

What if there was a different way of viewing the ordering of life? An orientation toward the wombing of social movements as opposed to a chronos-time, mechanistic approach to social change provides the spaciousness needed to look beyond our own lifetimes for transformative healing to come through future generations.

And even through my own imperfect, physical wombing, I have learned to pray a prayer that emanates from my innermost being: Make me a womb of love in all the areas in my life. Of the womb of individual human love, expressed through mothers, fathers, and primary caregivers. Of the womb of civil society, kin networks, faith communities, schools, civic groups. And of the womb of the earth, her fecund soil constantly birthing new life that sustains all of creation.

Reverie

That apocryphal night

Of me and I of it

As snow sealed the roads

My father tarped the house

And she, upstate,

Alone at the hospital,

On the elevator,

No, not alone,

a nurse

Cooing her

And Conducting.

Reading the stars in her eyes

“Don’t worry, child. Hush Honey.

All is okay.”

Her voice echoing down the long hall of time

Starched white, dark skin, eyes shining—

I cringe at the mystical magical trope—

Eyes as . . . mirrors

Sweat beads.

Her body rolls and cramps

Eyes undulate wide and clench,

Then sag.

The red sea beginning to lurch

A first sphinx step toward exodus

Together, they, joined

By the impossible unknown

Of that November night

Waves

Expectant and fearful

Following the stars and a column of fire

Not a railroad, but

A rhizomatic path toward freedom.

And now

Coal stacks billow bituminous

Darken the driven white

Dilate the iris

Obscuring the deep pools of night

Pray for the road of anthracite

And now when the storm comes

And the covers are thrown off

And the echo arrives

And the waters have crashed back

And now begin to rise,

When I alone in antiseptic halls,

Knowing something is about to be birthed . . .

Memory drips and smokes.

Will we flicker out,

Lost in the terrible furnace light?

Will we immolate ourselves in a shining truth?

Or will we clarify that which is impure?

Redeem and anneal us,

Suited for a perfect task.