J

There was a time when educators became famous for providing reasons for learning; now they become famous for inventing a method.

—Neil Postman

Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Immanuel Kant, William James, Friedrich Nietzsche, John Dewey, A.N. Whitehead, C.S. Lewis, Jacques Maritain, and Hannah Arendt all wrote essays or whole books on education. These major thinkers decided education was an important topic to weigh philosophically. Today we write handbooks for teachers. We debate policy. We aggregate best practices. We use school to score points in culture-war battles. When we debate the shifting ways we try to understand the world, education waits for the crumbs to fall from the tables of adjacent arguments. An area formative for everyone’s life, the highest-stakes environment for everyone’s kids, the arena where all of us come of age, education doesn’t feel like a serious topic for all serious thinkers to explore. It is a realm of technical problems, not imaginative ones. We assume we know what education is for. The task is simply to make it happen better. We engineer tighter ships with no idea where they ought to be sailing, or why.

It’s different at the college level. A wave of compelling books presses for the meaning of higher education: William Deresiewicz’s Excellent Sheep, Andrew Delbanco’s College: What It Was, Is, and Should Be, Martha Nussbaum’s Not for Profit: Why Democracy Needs the Humanities, Roosevelt Montás’s Rescuing Socrates, Frank Bruni’s Where You Go Is Not Who You’ll Be, Mark Edmundson’s Why Teach? and Why Read? We have no equivalent wave of books celebrating and pushing and trying to inspire the life of the school experience before college. Instead, education-conference schedules are filled with workshops on uses of AI, on well-being strategies, on techniques for differentiation, on leading through change, on building safe spaces, on so many techniques and practices grounded in what is called with articled reverence “the research”—but none on the meaning of the life we’re supposedly educating students to embrace.

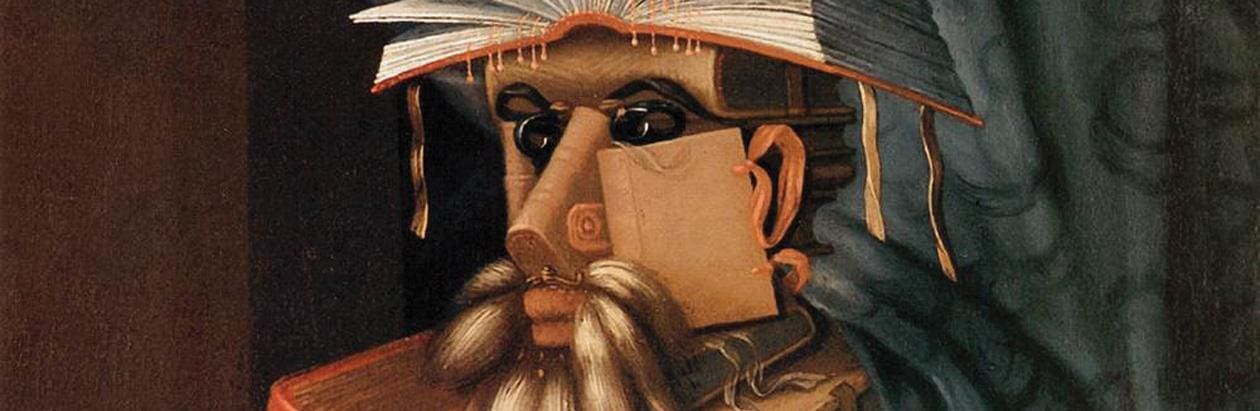

The Triumph of Technique

In an interview with Jonathan Haidt on his New York Times podcast, Ezra Klein observes a moral and imaginative hesitation in discussions about kids and technology:

Education has its own version of that parental hesitation. I think what Klein is exposing is that we are confident inside technical frameworks and disoriented outside them. And so we turn metaphysical or moral or imaginative dilemmas into technical problems because we think we understand how to navigate those. Jacques Ellul argues that our modern preference for technique results in a commitment to means and the near-absence of ends. Where technique reigns, the only end left standing is an implicit one: being successful at what technique can be successful doing. We measure but we don’t aspire. Technique is so ubiquitous—we’re like the two young fish in David Foster Wallace’s famous Kenyon College address who don’t even know what water is. According to Ellul, we are swimming in technique, and we barely register the implications. Schools have strong views about twenty-first-century skills but no point of view about the kind of life a young person should consider good for its own sake. Because we don’t wade into those waters, we treat education almost as a hackathon, a code to crack, a problem to solve, a system to optimize.

We lack a compelling shared image of what school is for because we lack a shared image of what a human life is for. We settle inside a default vision we’re confident isn’t contested, which is simply that students should be equipped to be successful. What we mean by educational success is using that equipment well to get credentialed for later success. The world is something we navigate and analyze. It is a linear, logical proposition. The whole journey of school becomes skill and credential acquisition. Alexandre Lefebvre calls this view of life “an unending tournament.” Your self, in that framework, is “an asset to invest in.” Young people today are told they need to be their own brand. That’s what we assume we all are, or else we’re afraid to say what we really think: we have no idea how to describe it any differently. Or else we have our idea and it’s demoralizing to confess. An education designed to produce efficient life seems destined instead to breed cynicism and emptiness. And we know what happens to vacuums in nature and in culture.

Education in the Meantime

Our accounts of what happens in school are also narrow and technical. To borrow the image John Stuart Mill used to describe the problem he saw with his own education: we are building well-equipped ships with rudders but no sails. It’s the reverse of Søren Kierkegaard’s parable of ducks in a duck town waddling into a duck church, where a duck preacher declares that God has given them wings to fly—they can fly—and the ducks all say amen, then waddle out of church. There’s almost no lift in accounts about school. We’ve turned the profession of teaching into an execution office, and our end game, despite every heroic teacher’s best effort to preach flight, is success at waddling.

The limitations are glaring. When AI chatbots were first introduced with some fanfare (and panic), the questions school people started asking involved how we were going to integrate these tools, as integrate them we all assumed we must. How were we going to teach their responsible use? How were we going to guard against the wrong kind of shortcuts they would no doubt introduce? What, in other words, were the right new techniques? We are less equipped to ask, What about these tools do we want, and why? What are the trade-offs measured against? How will we decide when inefficiency is preferable to efficiency because something larger is at stake? We also feel the limitations of technique in responding to world events and crises, tragedies and pandemics. We fall into reactive mode quickly. Lacking what Henry David Thoreau called “a bottom that will hold an anchor, that it may not drag,” we grope for a vocabulary to describe a kind of technique for teaching in the absence of larger ends. We think we don’t need an end, or else we’re unsure how to even formulate the challenge of an end. Instead we convince ourselves that describing the dynamic itself is enough. We say we are adaptive in the face of whatever comes. We’re more hesitant to ask what kind of conditions are and are not worth adapting to. Because how would we know? We are nimble, we say; not, We are lost. What we do while we wait for clarity we call being resourceful. We poeticize technique with the language of TED Talks, treating energetic description of the process as a good-enough version of the absent end. We whistle awkwardly and equally past playgrounds and graveyards.

We lack a compelling shared image of what school is for because we lack a shared image of what a human life is for.

Students have not chosen the larger context in which they are being educated. Neither have teachers. But if our reality is that our society simply does not have broad, shared clarity about what an education is for, or a human life, or a community for that matter, at least part of our job is to navigate being inside this tough transition. Sometimes we’re right at inflection points, and the fundamental questions of what education is for are contested—and rearranged. But we also may find ourselves teaching in a long meantime, when the stakes and the shared understandings are drifting and straining. Sometimes the virtue we need is courage to engage in contest, sure, but there may be times when what is called for is patience to abide. Some moments call for prophecy; others (more often) require wisdom. We might crave clarity and urgency, but what if a kairos is sometimes a meanwhile? Pressures on the larger modern liberal experiment are pressures on the assumptions that have guided liberal schooling too—not the techniques but the assumptions behind the whole enterprise. We don’t explore those assumptions enough. We also don’t realize how much pressure they’re under. We may need to churn these dilemmas for a while. The framing of the meaning and purpose of an education deserves our best attention, and the attention of our best thinkers. We can hope the philosophers won’t leave us alone. Poets either. We can hope some William James sets out to speak to halls full of teachers about the beauty and the momentousness of what they really do. But in the meantime, we shouldn’t only be busy figuring out chatbots and predicting needed skills for what we tirelessly call an unpredictable future.

In the meantime, we can at least try to describe school with more nuance, more poetry, more life. Education involves imagination and artistry and philosophy and ritual. The best form to capture its life and its meaning is probably not argument at all, in the end. We are not trying to create a new manual. We are not reverse-engineering anything. We should not spend the day in explanation, Ralph Waldo Emerson said. What if we tried spending it in portraiture? Or singing?

Thirteen Ways of Looking at School

With a nod to Wallace Stevens and his poem about a blackbird, here is a non-exhaustive list of ways to look at school with some imagination, in this meanwhile that we’re in. Anyone hoping for a syllable or two about good techniques or slam-dunk arguments about the Western crisis will be sorely disappointed. I am churning too, and doing school work in the meantime. What exactly is it that all this schooling is for, and what can it do when we educators find ourselves between big shared understandings?

- Making a dense net. Spanish philosopher José Ortega y Gasset writes, “So many things fail to interest us simply because they don’t find in us enough surfaces on which to live.” What we have to do, he goes on, “is increase the number of planes in our mind, so that a much larger number of themes can find a place in it at the same time.” A parallel image is of the mind as a net that builds capacity to hold more and more connections in its cells. School increases those planes and densifies those cells. This isn’t about simply knowing a lot of things so you can star at trivia night. It’s about building a rich internal framework for gathering new knowledge and new experiences. You want a nimble mind, but you also want what novelist Thomas Pynchon calls “personal density.” The cultivation of this density—dense learning—is the long game of school.

- Inheriting traditions and big bodies of knowledge. It used to be more obvious than it is now, but one of the main roles schools play is passing along an accumulation of prior learning. Richard Rorty, a university professor, not a high school teacher, argues that “education up to the age of 18 or 19 is mostly a matter of socialization—of getting students to take over the moral and political common sense of the society as it is.” Rorty acknowledges that some challenges to inherited common sense can be appropriate in high school, but he thinks college is where the real action of critical thinking happens. Since all the way down the educational ladder schools emphasize the development of critical thinking more than anything else, including inherited common sense, Rorty’s scheme feels like a drastic oversimplification these days. Still, it is a good reminder that you need to know a lot of things to be thoughtfully critical about anything—and maybe also that critique is not the end game of school.

- Meeting people who know more than you. One of the best things about school is that it offers you a sequence of accidental mentors. I say accidental because every student’s biography shapes who and what they respond to, and every teacher’s biography shapes what they have on offer. These aren’t scripted exchanges of expertise; these influences are unpredictable encounters. But the encounters show students what they can be and also introduce ways to understand the world that don’t simply exist inside students already. My favourite account of a teacher’s impact this way comes from Jerome Bruner, who describes a childhood teacher inviting him “to extend my world of wonder to encompass hers.” In a glorious summary, he says his teacher was “a human event, not a transmission device.” We should write that on the lintels of the doorpost of every classroom: Enter Here for a Human Event.

- Being pointed to books to read. How many teachers have changed a student’s life through the simple act of introducing a book or an author? This happened to me. My eleventh-grade English teacher kept me back at the end of class one day and handed me a collection of short stories. “I think you’ll like this book” is all she said and had to say. I devoured the book that very afternoon. Why? Because she customized this recommendation. There was no announcement to the class suggesting this good book—she handed it to me. I think you will like this book. In his memoir Teacher: The One Who Made the Difference, Mark Edmundson describes a high school teacher doing the same for him, holding him back after class, recommending The Autobiography of Malcolm X. His teacher said, “I think that you would get a lot out of that book.” Edmundson’s commentary is moving: “This took me by surprise, this business about myself.” The book recommendation is the teacher’s secret weapon for provoking self-discovery. Reading is the path we offer students for building expansive inner worlds while the outer world fractures around us.

- Experiencing community. Note that I didn’t say learning how to be a member of a community. School is its own community. We miss this dimension when we describe school as a training ground. Dewey challenged the training mentality of school as “mere preparation.” I’m tempted to say a healthy school community, with its rites and rituals and shared experiences, helps students become whole, or helps ground them for their later roles in larger communities, but I want to avoid any whiff of the instrumental or transactional. School is the form of community that surrounds young people in their formative years. It sustains their coming of age. In that capacity, it is an end in itself, a dwelling. Be in it.

- Practicing pluralism. Arendt describes school as a “halfway house”—not quite home, not quite world. It is, she writes, “the institution that we interpose between the private domain of home and the world in order to make the transition from the family to the world possible at all.” Like the world, this in-between space is full of variety and difference. Dewey called schools laboratories for democracy, and we might add that they are playgrounds of pluralism too. The introduction of disparate experiences and perspectives creates the condition not only for learning to live well with others but also for figuring out what you yourself might want to be and do inside the rush of possibilities you didn’t even know existed.

A focus on technique can leave school feeling like a place that studies recipes without ever preparing and enjoying real meals. All telescopes, never a star.

- Gaining skills, equipment for later work. What is usually seen as the very heart of what school is for I tuck here in the middle. To lean against an instrumental view of any young person, to say that the goal of their education is not simply filling their toolkits to go get a job, is to defend the attention of school to the whole life of a child. But that’s not to ignore a responsibility to help them become mature adults. Part of maturity is strength. You become strong by learning what you don’t know and by practicing what you don’t know how to do. Part of maturity is autonomy. School needs to equip students with what they need to move on from it. But let’s call that equipping work building a rudder, and let’s acknowledge that while an education does need to have that rudder, it also needs to lift sails and chart interesting routes on interesting seas.

- Enjoying a moratorium. Let’s ride that image of navigation. Let’s stay on that boat and climb up the masthead to the lookout’s perch, the crow’s nest described so lovingly by Herman Melville in Moby-Dick. Following his narrator up to that high vantage, Melville paints a picture of “unconscious reverie,” of “sublime uneventfulness,” of enchanted staring, all of which is a counter-note to the instrumental, skills-acquiring, résumé-building work that school can be seen to exist for. Some dimension of school has to be a protected space. Figuring yourself out and listening for your place in the world are not paint-by-numbers tasks. You do a lot of things other people ask you to do well in school. You also need some reasonable space and opportunity for what Henry James called “wondering and dawdling and gaping.”

- Experimenting, trying on new selves. We sometimes imply, or state outright, that the aim of education for students is to find their passion. Without care and nuance, this framing can mislead students into thinking a passion is already inside, waiting only to be released. A self is there, waiting only for recognition. A better description might be that, in school, students are trying out various relationships to the world around them. They are experimenting with what they want to value, both socially and intellectually. This is Ralph Waldo Emerson: “Around every circle another can be drawn.” School, in this light, is attention to this rippling out of interests, of responsibilities, of possibilities, of concerns. It is attention to what is outside you and what is not you.

- Rehearsing discipline. Why do we insist on asking students to buckle down on long tasks they have no interest in? Because it habituates them to be able to buckle down on the task that they eventually do become deeply interested in. The concentration required to read a long book carefully transfers to other work that requires real stamina. Staying with something, revising it, iterating on it, develops the muscles you will need to master the thing you care about. Writer Greg Jackson calls this habit “the long cultivation of skill.” To do something well is not simply a matter of choosing the right thing to do, expressing your passion. Instead, Jackson writes, you must make “hundreds of right choices in a row.” School practices that. I would have every student read everything at least one author wrote—the field doesn’t matter—just to practice this long attention.

- Experiencing wonder and astonishment. School is not primarily an arena of technique. It is a place of rich encounters. A focus on technique can leave school feeling like a place that studies recipes without ever preparing and enjoying real meals. All telescopes, never a star. There should be wonder and lift and life in every classroom. I’m inspired by the poet Mary Oliver’s note that her work was “mostly standing still and learning to be astonished,” and I’m chastened by Peter Sloterdijk’s claim that most scholarship now has assumed “a campaign against amazement.” (He calls the social sciences a “resolutely wonder-free zone.”) One of the purposes of school is to inspire students, to wake them to the world. A wonder-free skill set is a boat with one oar, rowing in circles.

- Feeling claimed by something. In his memoir, composer Jeremy Denk describes his childhood discovery of Mozart in these striking terms: “The growing, climbing notes were mapping onto me.” How different that is from “I developed a passion for Mozart!” David Brooks has called this “the capacity to be seized.” Dutch educational philosopher Gert Biesta has written that school is, perhaps, “a place of revelation.” This is all startling language, and it points to the catalytic work of school, which sets up conditions for the world not only to be discovered by young people but to actually lay a claim on them. School is where you learn that the things that are going to matter most to you are things that come to you. That great cheerleader of going your own way, Henry David Thoreau, wrote in his journal, “The theme that seeks me, not I it.”

- Receiving seeds that grow later. Thoreau also said of his time at Walden Pond that he “grew in those seasons like corn in the night.” In the night, when no one is watching what is happening. The paradox of the most successful school: you can’t see the real effects of what you’ve done until long after the fact. So we measure short-term growth and call it what we can, while the real work takes its time and happens a long way away from us.

There should be a final lesson about the incompleteness of these thirteen lenses, or the forever incompleteness of educational technique, and maybe also about the extraordinary stress and difficulty and generosity of teaching in the meantime. My final word, my final wish really, borrows language from Clare Carlisle’s biography of Søren Kierkegaard. For this Danish philosopher, she writes, “philosophy was not a swift trade in ready-to-wear ideas, but the production of deep spiritual effects that he hoped would penetrate his readers’ hearts, and change them.” School should be a community cultivating similarly deep, lasting effects and not, what it must so often feel like to young people and to their long-suffering, unsung teachers, a mobile dispensary of ready-to-wear skills—and endless, endless fiddling with techniques.