How long will it be until we are completely forgotten? Three generations? Four? After that, most of us will become nothing more than a faded smile on a photo that some unknown descendant will glance at with a passing curiosity: Who was this man? Our enduring significance is one of the greatest illusions we have while breath is in our lungs and strength is in our limbs. Soon enough, every one of us will fly forgotten as a dream. Our fears, hopes, sorrows, and whatever hard-won wisdom we’ve cobbled together will dissipate like a mist. “Meaningless,” we hear the Teacher from Ecclesiastes intone. No sooner have we become accustomed to the audacious ongoing fact that we are, then suddenly: we are not.

This haunting, humbling fact is a source of deep-seated historical dread. It permeates even the mightiest cultures. In ancient Greece, for example, the fear of being forgotten lurks just below the surface of their obsession with kleos. The term, usually translated as “glory” or “renown,” also had to do with what others said about someone after they passed. It had to do with how, or if, one was remembered. Only great men and women—the strong, eloquent, wise, beautiful—would live on in human memory. Achilles is one such great man. In The Iliad he expresses well the tension he felt as a hot-blooded Greek warrior on the eve of battle:

If I hold out here and I lay siege to Troy,

my journey home is gone, but my glory never dies.

If I voyage back to the fatherland I love,

my pride, my glory dies.”

We know Achilles’s choice and his fated end. Shot in the heel, he’s brought low, limping to his death. Yet his memory lives on. Millennia later, his deeds pass across our lips. But this once coveted immortality, we soon discover, is of little consolation to the man of war. When we come across Achilles again in The Odyssey, it’s as a chastened shade in the Underworld. Achilles instructs Odysseus, his comrade-in-arms at Troy, that it would be

better to break sod as a farm hand

for some poor country man, on iron rations,

than lord it over all the exhausted dead.

Achilles does not want to be remembered by the living but re-membered with the living. He would give anything—even a life of ignominious slavery—to enter such membership again.

Membership. To be a part of a greater whole. Many members, one body. When newcomers seek membership in our church, we ask them to share their story. These stories are never about the strong, eloquent, or beautiful demigods of classical epic. Rather, new members reveal their weakness, shame, and brokenness. These are what they bid us remember: how they have battled addiction and anxiety for years without success; how they bear the scars of abuse, self-inflicted and at the hands of others; how they have wandered without direction; how they have been directed by darkened hearts. If you listen long enough, you know that membership in a church is membership in Christ’s body, broken. And breaking all the time. If we are the feet and legs of Christ, then he has chosen us to limp through this world.

Sometimes I think the church should have a sign on its door: “The People Who Limp.” In the Old Testament, God’s people were the Israelites, the posterity of Abraham, Isaac, Jacob. Israel is the name given to Jacob, but only after he contends with God on the eve of possible war with his estranged brother. (Did he, like Achilles, debate heading back to Laban to live out his life in safety and obscurity?) In the story, Jacob holds his own in the wrestling match, but the angel—who turns out to be God himself—delivers the coup de grâce, touching Jacob’s hip, distorting it. It’s a dismemberment, of sorts, and the turning point in Jacob’s—and the people of God’s—life. From this point on he is Israel: the man who contended with God. But he is no Greek warrior. I like to imagine that for the rest of his days people recognized him, Israel, as the man with the limp. He probably leaned on a cane.

To become disciples of the living God, our understanding must become faith, our will must become love, and—most intriguingly—our memory must become hope.

Israel is God’s man and God’s people. Singular and plural. Israel is the second generation of the answer to the desperate prayers of Abram and Sarai. If you have struggled with infertility, you know how desperate and anguished such prayers can be. You know there are as many ways to wrestle God as there are ways to limp through this world. In their very advanced years, Abram and Sarai had likely reconciled themselves to the deep sorrow of their inability to bring about new life. They were just another broken, elderly couple. Who would remember them?

Yet God comes to them and promises that not only will they have a child, but they will have many children, whose number will exceed the stars in the heavens. Abram, the “exalted father,” becomes Abraham, “father of many.” If kleos is one way to beat back our mortality, children are another. In some ways, God’s promise would have sounded like immortality in Abram’s pagan, human ears. He would birth a mighty people. His name would never be forgotten. Abraham would eventually die, but not before the birth of a son. Isaac, son of the laughter who ended the nights of sorrow. Isaac, son of the laughter at a God who is as audacious as he says he is.

Around the sixth year of our marriage, such laughter was hard to come by. At that time I hated hearing the story of Abraham and Sarah, not to mention Jacob and Rachel, Hannah and Elkanah, and Elizabeth and Zechariah. God seems to have a thing for infertile couples. They are, if nothing else, fertile ground for the miraculous. Yet almost nothing is more disheartening than the story of infertility ended while yours languishes on indefinitely. Children had been a dream of ours early on in our marriage, but our first six years were riddled with niggling uncertainties, then invasive tests, countless appointments, surgery, emptying our admittedly small savings account, and waiting, waiting, and waiting for what would be one disappointment after another. What started as an unpleasant possibility became an all-consuming fact: we could not have children.

When we joined our church several years ago, this was our story. This was our small part in the body, broken. It was how we had learned to limp. In stilted prose, we shared what the pain of these years felt like and how the deepest hurt during that time was not really that our family line would stop with us, or that we would be unknown in our old age, or even that we felt insufficient as a man and a woman. All of these troubled us to varying degrees, but the numbing dread came in the dead of night when we just couldn’t shake the haunting suspicion that God had forgotten us. Where was he? Did he hear us? My God, why have you forsaken us? Silence.

Today we have four children. Like I said, no one who is currently struggling through infertility loves hearing the stories of infertility ended. But the story we wanted people to remember—the story that all the broken members who have joined our church want remembered—is not simply about the joy of a struggle ended, but about peace found in the midst of struggle. Months before we discovered we were expecting twins, we had come to rest in the assurance that with or without children God remained unchanged. He is who he says he is. Always. We held that. And if we were his, then barren or otherwise, we had our work to do.

In a wonderful little book on discipleship, Rowan Williams draws on St. John of the Cross to reflect on how the theological virtues—faith, hope, love—are simply the maturation of basic human capacities. To become disciples of the living God, our understanding must become faith, our will must become love, and—most intriguingly—our memory must become hope. “Hope,” Williams writes, “is hope in relation to that which does not go away and abandon, relation to a reality that knows and sees and holds who we are and have been.” When the church hopes it is not an irrational leap in the dark, but a trust that the God who acted before will continue to be that God forever. Believers are people who hope in a God by remembering his great deeds. They look ahead in hope by looking back. It’s why the Old and New Testament are replete with God’s imperatives to remember. Remember you were slaves in Egypt. Remember I delivered you. Remember my law when you enter the land. Remember to keep it. Remember my body, broken for you, and my blood poured out. Remember I will come again. Remember you are broken. Remember you limp through this world, so do not get too comfortable in the rebellious kingdom. Remember you limp so you might remember to lean.

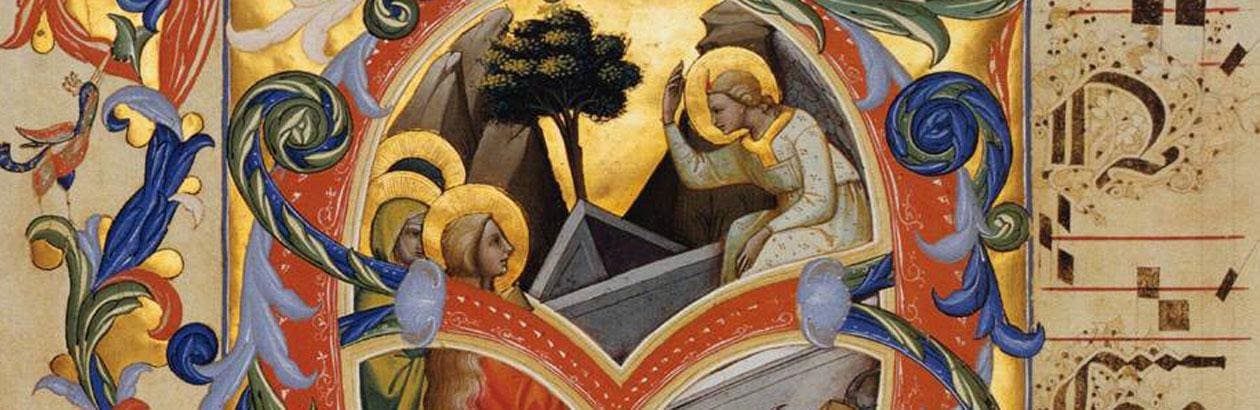

When Virgil guides Dante through the broken masses of hell in the Divine Comedy, the anxiety of being forgotten is palpable. Many of the damned are curious to know what others are still saying about them. They are desperate for Virgil and Dante to speak their names among the living so whatever glory and renown they had on earth might still be spoken for a few centuries longer. One of the most beautiful, consolatory subtleties in the Christian epic is how this anxiety of being remembered disappears in Paradise. In Paradise, no one worries about how their legacy is passed on by their fellow creatures. The shades in heaven rest in the knowledge that their Creator has remembered them. Here is the peace to counter Achilles’s and all secular, pagan dread in the face of death. Because when the Being who is love and life and mercy remembers you, when he tells you that your name is carved into his hands and he has numbered the very hairs on your head, you are not merely an idea flitting through a mind. When God remembers us, he summons us into membership again with the body, resurrected, whole, and holy. To be remembered by God is to be translated into a new being. Body healed. Sin forgotten. Life eternal.

I told him how God’s power came despite our weakness. God erupted into our lives, and Eli and his three siblings are answers to prayer. I want him always to remember this.

We named our firstborn Eli, which means “My God.” The name is a bittersweet memento. On the day Jesus’s body was broken he cried out, Eloi, Eloi, Lama Sabachthani. “My God, My God, Why have you forsaken me?” It is easy to forget the profound mystery that the God we worship knows the primal dread of alienation from God. I don’t pretend to understand it. But Christ knows the heart-palpitating shudders of our darkest of nights. What sets us apart, then, is not that we will never rage and wrestle with the God who makes us—God’s people remain Israelites—but when we do, our struggle is prefaced by the foolish wisdom of declaring, hoping this God is “mine.”

This past Christmas Eli asked me at bedtime to tell him a story about something from a time before he remembered. I told him our story, which is also now his story. I told him how God’s power came despite our weakness. God erupted into our lives, and Eli and his three siblings are answers to prayer. I want him always to remember this.

Of course, my son wasn’t there. He has to take our story on trust. But isn’t this the case every time God’s people are asked to remember? The body, broken, is held together by the faithful sharing of such stories. We need to tell and retell them. They join us one to the other, encouraging us to look back in wonder at how God has acted for his people—individually and collectively—and to look ahead with anticipation and hope for where he will show up next.