T

The sociologist Zygmunt Bauman once declared that globalization makes us either tourists or vagabonds. There are wealthy adventurers passing through for a thrill, and desperate locals hoping for a crumb from the in-flight tray table.

A third category, the pilgrim, does not seem to have made it into Bauman’s account, and yet it should have, for pilgrimage is the aboriginal form of travel of which tourism is a recent deformation. Pilgrimage, of course, permeates the Bible. The Hebrew word hag is a command (Exodus 23:17), and its neglect is a source of corruption (I Kings 12:28). To take away pilgrimages to Jerusalem from the Biblical accounts of the life of Jesus would be to gut them. No pilgrimage, furthermore, would mean no Pentecost. Christ’s charge to the Samaritan woman that “the hour cometh, when ye shall neither in this mountain, nor yet at Jerusalem, worship the Father” has proved not an abrogation of the pilgrimage tradition but its expansion, only multiplying the holy mountains where the Father is worshipped “in spirit and in truth.”

The tourist seeks interesting places. The pilgrim seeks to realize the way that a particular place freshly articulates the truths of faith. Hence the pilgrim, like the tourist, can be deeply impressed by the scale of the Parthenon, but equally overwhelmed by Mars Hill just below, where Paul’s message, then mocked, would soon make of that Parthenon a church. The pilgrim, like the tourist, will be awestruck by the Roman forum, but struck all the more—looking out at the mushrooming church domes over the Eternal City skyline—that the forbidden religion overcame imperial might. Pilgrims, like tourists, can’t help but be affected by the pyramids, only to then sense the shattering contrast of the Sinai wilderness, where the man-made pyramids are dwarfed by far larger natural ones, and where Pharonic splendour is both tempered and judged.

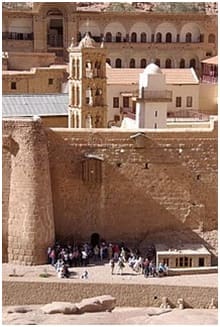

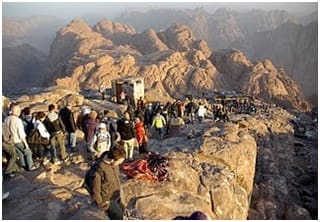

Though a historic place of pilgrimage, Mount Sinai today is threatened by tourism. Ease of access and luxurious guest quarters have transformed it into a tourist destination in only the last few decades. PBS television specials on St. Catherine’s monastery have done much to publicize the unique significance of the monastery’s architecture, icons, and manuscripts, but have also contributed inevitably to the traffic. On my recent pilgrimage to Sinai, some of the people I spoke with were like ghosts. They are professional adventurers, having just come in from touring the Arctic Circle or backpacking the Sudan, relating with enthusiasm a recent triumph of visiting a place you’ve never heard of and will probably never hear of again. Sinai was (just?) next on the list. I described to one of them the significance of the trip for me as a pilgrim, and offered, upon request, a rough sketch of the book of Exodus. They appeared interested, puzzled at its unusual significance, intrigued enough to say that perhaps on the next trip they’ll read the Bible a bit. Of course, God’s mercy rains down on both the pilgrim and tourist, and one can sense here the set up to a riff on the prodigal son, where the tourist gets the blessing, and the self-righteous pilgrim—already fulfilled—gets nothing at all. But just as the story of the prodigal son does not endorse prodigality, mass tourism at a place as special as Sinai is still a shame.

Those who tend the holy sites know how to sort out the pilgrims from the tourists. God help those who fake it, but pilgrim status—the willingness to worship—is the backstage pass. As tourists are ushered out, pilgrims are permitted to stay. Go to Sinai today and you will be escorted up the mountain by accommodating Bedouin (stopping for Snickers and Twix at the myriad Bedouin-run snack booths along the way). After witnessing the sunrise with literally hundreds (perhaps thousands) of fellow travellers, you will descend back to the monastery and be crammed through the lower levels of the compound during visiting hours, rushed through the church and museum, and then quickly escorted back to your luxurious accommodations.

But send even the slightest signal that you are a pilgrim and everything changes. Perchance you will speak at length with the monks (easy to do, as one speaks eleven languages); or witness, for example, the saintly combination of penetrating intelligence and childlike joy in Father Justin; or be permitted to stay for a service (far too much of a commitment for the tourist); or even stay overnight within the monastery. It’s not that the monks wouldn’t extend such hospitality to the average tourist; instead, it’s that the average tourist is not interested in this level of engagement.

At one of the services at St. Catherine’s sixth-century Church of the Transfiguration, a cadre of Russian pilgrims piled in for the liturgy, just after all tourists uninterested in to participating were politely asked to leave. The service began with the veneration of the relics of St. Catherine, after which a ring was received, a ring that instantly distinguished the pilgrim from the casual visitor. Worship began, and hours later, when the elements suddenly emerged through the Royal Doors of the iconostasis, the reverent Russians collectively hit the deck. Would that more of us sinners would dive for cover like that. These were, after all, pilgrims. When, during the same service, one of them underestimated monastic vigilance and slipped out a forbidden video camera, one young monk noticed the disruption. With a disappointed smile, he gave him a look that silently asked, “You’re not a tourist, are you?”

Because of the bond of pilgrimage, a visiting American Protestant, for example, will likely find more in common in conversation with a Bedouin Muslim or observant Jew than with a casual American tourist who is checking off one more exoticism on their “places to see before you die” list. Sinai proves Bauman right: Our globalized world is divided between tourists and vagabonds, between the mobile rich and those who facilitate their play, between the Sinai tourists plugging for a monorail and the Bedouin who cater to them. But with a small measure of devotion, any tourist or vagabond can grow into a pilgrim (just as any pilgrim needs beware lest they devolve into a tourist). Such pilgrims—staffs in hand—will continue to look upon both tourists and vagabonds with puzzlement, wondering why it is they still have on their shoes.