“Now Venice, as she was once the most religious, was in her fall the most corrupt, of European states. . . . The dying city, magnificent in her dissipation, and graceful in her follies, obtained wider worship in her decrepitude than in her youth, and sank from the midst of her admirers into the grave.”

—John Ruskin

S

Since 1895, an international gathering of artists has converged in Venice every two years. Known as the Venice Biennale, it is where the nations of the world send their most fashionable cultural athletes to compete. The lagoon city, once known as La Serenissima (the most serene Republic), is the optimal arena. Even if the new art is a bust, the city, teeming with churches and paintings by Titian, Tintoretto, Bellini, and Veronese, is guaranteed to come through. But some years visitors get it all, the best of old and new combined, and this is one of those years. For starters, if the Venice Biennale is the World Cup of art, Anish Kapoor’s show at the Gallerie dell’Accademia is a game-winning bicycle kick.

The Keys of Kapoor

The British-Indian Kapoor is best known for the kind of etheric engineering that produced Chicago’s monumental Cloud Gate (aka “the Bean”). For his contribution to the 2022 Biennale, he collaborated with scientists to produce the “world’s blackest black”—that is, carbon nanotubes that reflect almost no light, mimicking a black hole and concealing topography: a twenty-first-century trompe-l’oeil.

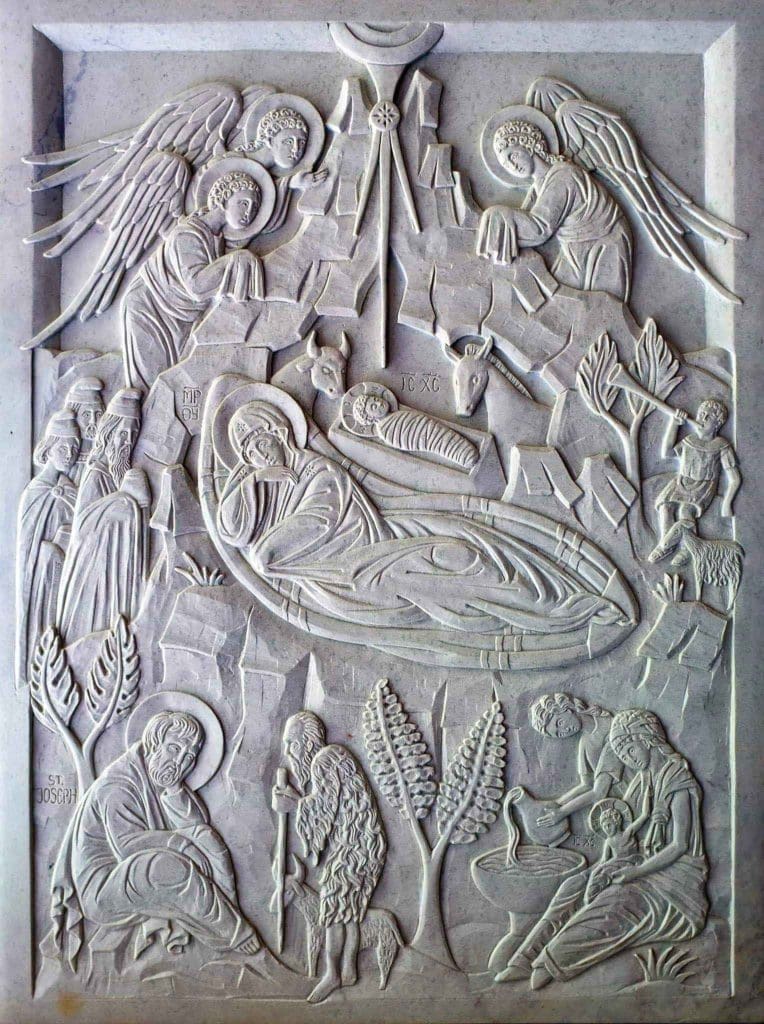

While most attention has been given to rival artists challenging Kapoor’s patent on Instagram, far more noteworthy is Kapoor’s decision to take on the lagoon city’s most important collection of art. The Marian icons in the Gallerie dell’Accademia, bored by most of the Biennale’s ephemeral interventions over the decades, seem delighted to be finally engaged. Pleased by her new gallery companion, a fourteenth-century Mary by Paolo Veneziano upstages Kapoor by allowing her divine son to leap from her apophatic womb. Christ reaches out not to curse but to bless Kapoor’s nanotech square, as if to illustrate that “the light shines in the darkness, and the darkness has not overcome it” (John 1:5).

Giovanni da Bologna’s Madonna of Humility, directly across from Kapoor’s encased square, appears to be smirking with amusement, but I think she is actually impressed. For Kapoor offers no reprise of Kazimir Malevich’s black square from a century ago. Upon circumambulation, the concealed convexity of Kapoor’s square resembles a baby bump. When the mound is noticed, comparison to Jacobello del Fiore’s image of the pregnant Virgin just behind Kapoor’s installation is unavoidable. And her baby, if one looks closely, reaches out to bless the darkness as well. Thanks to such assistance, Kapoor’s black becomes especially beautiful, offering not despair but plenitude; not mere darkness, but a light so bright it cannot be taken in.

Kapoor’s black becomes especially beautiful, offering not despair but plenitude; not mere darkness, but a light so bright it cannot be taken in.

Still, I wonder if comparing Kapoor to Marian icons is too easy—low-hanging fruit of the womb. It might be better to understand Kapoor’s voids as a refutation. Not a complement to the Christian visual culture of Venice, which continues to draw so many art pilgrims, but a gentle chastisement. For Kapoor’s pregnant square is in conversation not only with the icons around it but also with the image that most viewers will miss just above it. Kapoor has staged his void right below an image of God the Father that decorates the ceiling of the gallery itself.

The Christian tradition at its best, while verbally referring to God as Father, insists that this Father transcends visibility or sexuality as it is humanly understood. “You saw no form on the day that the Lord spoke to you at Horeb out of the midst of the fire,” thunders Moses in the fourth chapter of Deuteronomy. “The divine is neither male nor female,” wrote the early church father Gregory of Nyssa, “for how could such a thing be contemplated in divinity?” Yet, if God the Father is not male, why then does the Christian visual tradition continue to almost universally so convey him? While virtually absent from the entire first millennium of Christianity, such imagery began to proliferate in the second millennium, largely as a result of Christian disunity. And such imagery covers Venice like the plague, especially at the Accademia itself.

Is it possible to understand Kapoor’s show as a nudge to the earlier wisdom of the Christian tradition? Perhaps each of Kapoor’s voids, which are generously peppered throughout the gallery, could be paired with misleading images of God the Father in the same galleries. For example, in Daniel in the Lion’s Den (1663–64), Pietro da Cortona depicts a greying godhead with a glowing crucifix unconvincingly emanating from his robe. It is a beatific vision fit for Pinterest, and Daniel can’t be blamed for preferring the den. Kapoor’s convex mirror installed in the Accademia courtyard, however, is far closer to traditional Christian visual restraint. The mirror’s reflections offer only architecture and sky, along with any viewers who have gathered around—divine images that are satisfyingly indirect. Even so, the patient viewer will notice that from one particular angle, Kapoor permits a statue of Christ to be elegantly reflected in the mirror as well. “No one has ever seen God; the only God, who is at the Father’s side, he has made him known,” announces the Gospel of John. Christians may have forgotten this, but Kapoor, who conceals Christ in the side of the mirror, has not.

Perhaps Kapoor’s evident reverence for the image of Christ explains why not only black but red dominates the exhibition as well. A lower-floor room brings back a Kapoor crowd-pleaser, a cannon that fires pigment into a corner, slowly piling the room with splatterings of red wax. But this evokes far more than the Venice chainsaw massacre. Most would consider it an unforgivable overreach to suggest these projectiles be understood as cannonballs of eucharistic wine charitably pulverizing unbelievable depictions of deity. But Kapoor makes the move himself. He offers a meditative white room enhanced with only a red side-wound split in the wall. The piece’s title is not exactly ambiguous: The Healing of St. Thomas. Like it or not, the red has been interpreted for us, by the artist, as the wounds of Christ.

“Blessed are those who have not seen and have believed,” Christ says to Thomas after Thomas inserts his finger into the wound; yet Christian art history has not been satisfied with faith. Instead it offered to atheists the very image of the god they (rightfully) don’t believe in, trading uncreated light for a bearded old man in the sky. The scandal is such that one might even interpret the entirety of modern abstract art not as a haphazard burst of mid-twentieth-century creative energy but as an attempt at correcting Christianity’s visual caricature of the Christian God. But if abstract art is medicine for the church’s swollen visual culture, it required Anish Kapoor to most directly administer the dose.

One might even interpret the entirety of modern abstract art not as a haphazard burst of mid-twentieth-century creative energy but as an attempt at correcting Christianity’s visual caricature of the Christian God.

In short, when Kapoor’s pools of darkness are put in conversation not just with the Marian icons that surround it but with the images of the Father throughout the gallery, Christianity is reminded of ancient Jewish wisdom, and Venice—the city famous in this history of art for colore—is audited by infinite blackness. Tired iconography is not rehearsed but refreshed with complex refractions of heavenly light. Spasms of red, moreover, offer the unbelief of Thomas, and of our hypermodern world, an opportunity to heal. Like the Muslim who holds the keys to the Holy Sepulchre to keep it from warring Christian factions, Anish Kapoor has offered divided Christians the corrective they could not offer themselves.

Anselm’s Ladder

But if Anish Kapoor sets his sites on a theological critique, Anselm Kiefer’s show at the Doge’s Palace takes aim at Christianity’s political abuses; and by challenging Venice’s political history, Kiefer indirectly undermines the Venetian ambitions of contemporary powers as well. Kiefer is most well-known for his grizzly recollections of Germany’s national failures. Figuratively and sometimes even literally, he paints with sackcloth and ashes, which makes him the right artist for this job. Kiefer interrupts Venice’s soliloquy about its own splendour just as he has for his native Germany; and the Ducal Palace, which John Ruskin called “the central building of all the world,” is stronger for it.

If Venice was the “great theater of her own myth,” the Ducal Palace is centre stage. To visit Kiefer’s show therefore requires wandering through room after room of Venetian triumphs painted by the city’s most famous masters after a 1577 fire. Kiefer’s choice of rooms for his intervention, the Voting Hall (Sala del Scrutinio), is not insignificant. Venice’s conquering of Christian Zara (modern-day Zadar, Croatia) was one of the most embarrassing episodes of the Crusades—practice for the infamous sack of Constantinople in 1204. But now, Kiefer’s work conceals Tintoretto’s The Conquest of Zara (1584), conforming the Ducal Palace much more closely to the principles of Christ. (To be sure, this was also accomplished three hundred years ago, when the Orthodox artist Panagiotis Doxaras deconstructed Venice’s Ducal Palace at the Church of St. Spyridon on the Greek island of Corfu, but few people know their art history anymore, so Kiefer must suffice.)

Despite what viewers might have come to expect, or imagine they are supposed to expect, from Kiefer, there is little cynical about this installation. Again it was Ruskin, the great British student of Venice, who taught us that “the function of ornament is to make you happy . . . the expression of man’s delight in God’s work.” In the same way, Kiefer’s ornamental arrangements of zinc, paint, lead, gold, shoes, and shopping carts make modern viewers (at least this one) happy as well.

Kiefer exaggerates the winged lion flag of Venice not to mock Venice’s maritime empire but to tell the truth about it. When the flag is fully unfurled, so are the sins that Venice concealed from view. Her sins, however, are exposed not to be exhibited but to be forgiven. The red figures beneath Kiefer’s re-creation of the Ducal Palace appear, at first, to be grim reapers bearing sickles. But they might also be references to that event alluded to in hundreds of Venetian paintings: the last judgment. To see bodies emerging from the sea cannot help but reference “when the sea shall give up their dead” (Revelation 20:13).

This might seem a forced interpretation, were it not for Kiefer’s unavoidably central empty tomb. It is almost as if Kiefer is alluding to the now destroyed Venetian replication of Jerusalem’s Holy Sepulchre that once stood nearby. The tracings around the coffin simultaneously reference the circumambulating of Easter pilgrims and, as a friend suggested to me, the crown of thorns as well. Kiefer thereby replaces Tintoretto’s celebration of Venetian conquest with the earlier, and more lasting, conquest over death. It was, after all, the risen Christ who emboldened the first Venetians to raise a city from a lagoon. This is the humbler Venice that was quietly preached by her friars and more recently by Ruskin. This is the Venice that, well before Kiefer, had long been undermining her own myth.

Kiefer’s inclusion of menacing U-boats is a reminder of the modern naval warfare that Venice’s maritime empire did not endure long enough to see. Just above these submarines, however, is the humble heavenly chariot, another direct evocation of the hereafter from an artist who, at seventy-seven, certainly has the hereafter on his mind. Each cart is filled with different materials, almost as if to reference the apostle Paul’s remark that our earthly accomplishments comprise “gold, silver, precious stones, wood, hay, straw” (1 Corinthians 3:12). On that day, “each one’s work will become manifest, for the Day will disclose it, because it will be revealed by fire” (v. 13). Kiefer’s chariot asks us what Paul does: Which of our works will last?

Then there is the exhibition’s central moment—a ladder rising from the lagoon. To be sure, the ladder might be understood as a ladder to nowhere, just as Kapoor’s blackness might be understood as a blackness of despair. But a more natural interpretation—consider the paintings that enhance the lagoon’s countless churches and museums—is that it is the ladder of Jacob. Jacob’s words after seeing the ladder apply to Kiefer’s exhibition, and to Venice, as well: “Surely the Lord is in this place, and I did not know it” (Genesis 28:16).

Even so, it is increasingly difficult to discern that presence in the city of Venice itself. The armies that could not conquer her have now been replaced by hordes of tourists who have. What the Ottoman warships could not accomplish the cruise ships, compounded by climate change, will. The vanity of the Biennale culture—artists’ promo videos run on loops in gallery fronts featuring them in Ferraris and on Jet Skis—is tediously obscene. But Kiefer reminds Venice, and the global tourist class that constitutes her real residents, of the swampland from which she began following the fifth-century Lombard raids.

It is a mark of Ruskin’s gift that the best commentary on Kiefer’s swamp paintings may have been made more than a century and a half ago by Ruskin himself:

If the stranger would yet learn in what spirit it was that the dominion of Venice was begun, and in what strength she went forth conquering and to conquer, let him not seek to estimate the wealth of her arsenals or number of her armies, nor look upon the pageantry of her palaces, nor enter into the secrets of her counsels; but let him ascend the higher tier of the stern ledges that sweep round the altar of Torcello.

Indeed, Kiefer’s ladder may also be a reference to Venice’s ancient church of Torcello, whose campanile can still be ascended today. To travel the way there, past pilings enhanced with miniature votive chapels, is to travel to Venice’s fenland conception, when her faith was comparatively pure. The gold of Torcello’s mosaics, and of the earliest ones at San Marco, and the gold in Kiefer’s installation, only indirectly refers to God’s glory, without daring to show God the Father himself.

Kiefer’s message, to me at least, is as apparent as the city of Venice is beautiful. Her famous Marriage to the Sea, once annually renewed by the doge with dazzling ceremonial flair, has faltered. The more enduring partner in the arrangement is pummelling the city with increasingly devastating floods. I may have knelt at St. Mark’s dampened tomb in my sneakers, but my children may need to venerate the Gospel writer’s remains with snorkels and flippers instead.

Still, despair does not behoove us. “And I saw the holy city, new Jerusalem, coming down out of heaven from God, prepared as a bride adorned for her husband” (Revelation 12:2). Venice’s hope, and ours, is a better and more lasting union—a marriage to the sky.