I

“I don’t know about the others, but I was in awe of the tenacity, durability, and fearlessness of human thought, especially that thought within which—or rather, beneath which—there loomed something larger than thought, something primeval and incomprehensible, something that made it impossible for men not to act in a certain way, not to experience the urge for action so powerful that even death, were it to stand in its way, would appear powerless.”

These words come from the diary of Aleksandr Arosev, a member of the Bolshevik Party who commanded military detachments during the October Revolution, the 1917 coup d’etat that transformed Russia from a fledgling parliamentary democracy into a dictatorship of the proletariat. Like many Russian revolutionaries, Arosev’s political career began in his teens, when he attended socialist reading groups with like-minded, peasant-shirted students like his childhood friend Vyacheslav “Molotov” Skryabin, the same Molotov who would later sign the USSR’s non-aggression pact with Nazi Germany. Their interest in Marxism was largely academic: an effort to understand the world and shape it in their image. But for some, as the above quote indicates, the seemingly omniscient philosophy also appealed to their emotions, mysticism, and spirituality—sensibilities that, in previous centuries, would have been quenched by the teachings of Orthodox Christianity.

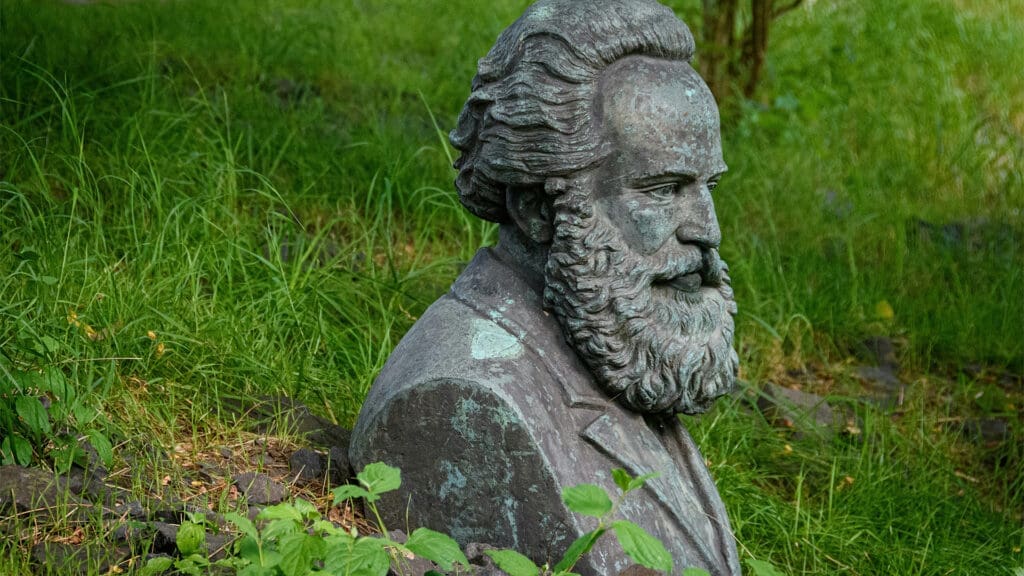

Arosev’s writings feature prominently in historian Yuri Slezkine’s monumental 2017 study, The House of Government: A Saga of the Russian Revolution, whose 1128 pages make the compelling if initially confounding argument that Bolshevism was as much a religious movement as it was a political one. Confounding because the Bolsheviks—embracing Karl Marx’s assertion that “religion is the opium of the people”—outlawed religion, destroyed places of worship, and persecuted worshippers. Compelling because, despite their virulent atheism, their faith in—and enthusiasm for—their otherwise secular ideas arguably bordered on religious ecstasy.

Bolshevism wasn’t so much a break with traditional religion as its reinvention into a faith befitting of society’s proletarian future.

Slezkine wasn’t the first to argue in favour of Bolshevism’s religious character. Similar claims had already been put forward by the likes of philosopher and theologian Nikolay Berdyaev, socialist writer Maxim Gorky, and Bolshevik revolutionary leaders Anatoly Lunacharsky and Alexander Bogdanov. While some believe that the similarities between the Bolshevik Party and religious institutions like millenarian sects and Russia’s Orthodox Church are little more than structural resemblances—the way airplanes resemble birds—others argue that the former actually grew out of and is inseparable from the latter, that Bolshevism wasn’t so much a break with traditional religion as its reinvention into a faith befitting of society’s proletarian future.

The question of Bolshevism’s religious character has helped historians make sense not only of the movement itself but also of an even bigger question: why a communist uprising succeeded in Russia when elsewhere it did not.

Bolshevism’s religious character can be illustrated on multiple levels. The highest and broadest of these is home to contemporary historians like Hans Mayar, Emilio Gentile, and Jacob Talmon, who—following the lead of German American philosopher Eric Voegelin—regard all totalitarian ideologies as secularized forms of religion, substituting God with government, Scripture with manifesto, and conversion with party membership.

One level below, one finds scholars who believe that Marxism is itself rooted in medieval Christianity, specifically in radical reformers like Thomas Müntzer, a preacher during the early years of the Reformation who used the Bible’s pleas for care and compassion as a rallying cry in his fight to free Germany’s peasantry from the shackles of feudalistic serfdom—not unlike how Russia’s socialist revolutionaries called on Marx in their struggle to dethrone the czar. “According to some,” historian and author of Russian Citizenship: From Empire to Soviet Union Eric Lohr told me in an interview, “Müntzer was the real father of the October Revolution.”

Zooming in closer still, there are arguments for why Russian Marxism is connected to Russian Orthodox Christianity. Many revolutionaries were the sons of priests, after all, and even if they rejected religion as a whole, this doesn’t mean their religious upbringing had zero impact on their worldview. “There is good research on the role of Orthodoxy shaping political activism,” Valerie Kivelson, a historian and author of Russia’s Empires, told me. “Dominant religious cultures often trickle into minority cultures.”

The Orthodox Church certainly had a profound impact on golden age Russian literature, which revolutionaries like Arosev, Molotov, and Vladimir Lenin consumed with the same fervour as they did the collected works of Marx and Friedrich Engels. Although treasured authors like Leo Tolstoy and Fyodor Dostoyevsky were banned in the USSR, its leaders did not deny their genius. Tolstoy, who popularized the wearing of peasant shirts among middle-class youngsters to show their hostility toward the landed aristocracy, particularly appealed to revolutionaries. Excommunicated from the Orthodox Church for questioning its spiritual integrity, Tolstoy outlined his version of Christianity in non-fiction essays like “The Kingdom of God Is Within You” and his final novel, Resurrection, in which a Russian prince relinquishes his land, titles, and serfs. This form of Christianity abandons ritual and hierarchy in favour of the same selfless sentiments that animated many professional Marxists. While Lenin criticized some of Tolstoy’s teachings in his essay “Leo Tolstoy as the Mirror of the Russian Revolution,” he still regarded the author as a frontrunner to his own revolutionary struggle:

Finally, there are studies like Slezkine’s House of Government, which distinguishes Bolshevism’s religious character from that of other totalitarian, Marxist, and Russian Marxist groups. Written in the same vein as Leszek Kołakowski’s seminal Main Currents of Marxism: Its Origins, Growth and Dissolution, House of Government argues that Bolshevism is akin to millenarianism, commonly defined as the belief in an impending and fundamental transformation of society to usher in an everlasting age of peace, prosperity, and justice. Further, it argues that Bolshevik anticipation of a world revolution to overthrow the global capitalist order not merely resembles but actually evolved from the Christian belief in judgment day and the second coming of Christ.

As Soviet anthropologist Sonja Luehrmann and historian of modern Christianity Todd Weir note in their review of House of Government for The Immanent Frame, “The sheer volume of materials presented by Slezkine—letters and journals as well as published speeches, memoirs, and works of fiction—leaves it hard to doubt one of his central claims: that many of the revolutionaries who built the Soviet state were animated by a fervent expectation of a radically new world, not unlike the expectations of revivalist movements.”

Given this connection, it should come as no surprise that Bolshevik leaders readily adopted symbols and practices associated with the Orthodox Church. In short time, says Lohr, “paintings of saints at icon corners were replaced with pictures of Lenin. They also held self-criticism sessions in the party where people would do what used to be called confession,” reflecting on whether their actions were in line with the tenets of Marxism-Leninism.

The religious character of Bolshevism was not restricted to the conduct of its leaders. Richard Hernandez, a historian of twentieth-century Russia, reflects on the religious language of party-sanctioned autobiographies of ordinary workers like Semën Kanatchikov. One of Bolshevism’s earliest disciples, Kanatchikov grew up in an Orthodox peasant family before joining the labour force in Russia’s bourgeoning industrial sector—an experience that typified “thousands of others who would eventually turn to socialist ideas both to explain and shape their social existence.”

According to Hernandez, “Bolshevism’s public ritual and ideology had powerful subjective effects that place it in a category apart from most other secular ideologies, even when those ideologies have pseudo-religious accoutrements of their own.” He notes that many worker-writers’ autobiographies are written like hagiographies, stories of saints, with authors describing their conversion to Bolshevism as canonized theologians like Saint Augustine of Hippo describe their relationship to Christianity. For Kanatchikov, writes translator Reginald Zelnik, Bolshevism was more than a political cause; it was the destination of a lifelong search for higher truth that filled his earthly existence with purpose and “almost teleological meaning.”

Kanatchikov’s religious language is not an empty literary device but evidence that Bolshevism assumed a space in his soul that had previously been occupied by Orthodoxy.

“The pilgrim in Kanatchikov’s case,” adds Hernandez, “finds his ‘profession’ and ‘priesthood’ not in Christ but in the revolutionary movement in its Bolshevik incarnation.” His allegiance to the party wasn’t a purely logical decision made in his own self-interest; it also spoke to “affections and movements of the heart.” To this end, the historian asserts that Kanatchikov’s religious language—he likens a socialist matriarch to a “prophetess” instructing catechumens and calls a factory a temple, one to whose sounds of industry “the trumpets of hosts of archangels could not compare”—is not an empty literary device but evidence that Bolshevism assumed a space in his soul that had previously been occupied by Orthodoxy. Crucially, Kanatchikov looks back on his pre-revolutionary life in unquestionably religious terms, describing his flirtation with women, vodka, and other worldly pleasures at the expense of committing himself to Bolshevism’s transcendent values as having fallen “into sin” and becoming “possessed by the devil.”

“Class-conscious workers,” writes Hernandez, “held acts of selflessness and self-sacrifice in very high esteem. Kanatchikov’s references to virtuous suffering are numerous. He highlights martyrdom, for example, as the ultimate sacrifice a worker could make for the revolutionary cause.”

If Bolshevism rejected the existence of God—any god—their confidence in the inevitable march of history and the communist utopia awaiting at its terminus was functionally tantamount to divine providence. Moreover, their faith in their atheistic ideology arguably arose from the same place and evoked the same feelings as the priests whose idols they destroyed: concern for one’s fellow man, desire to rise above suffering and injustice, impatience for the arrival of judgment day.

For every academic who has argued in favour of Bolshevism’s religious character, there have been two, three, perhaps five who insisted that the resemblance between the party and its supposedly Christian influences were just that: resemblances.

“Yes, they read Tolstoy and Dostoyevsky,” says Lohr. “But then again, they were fervent atheists who destroyed every church and synagogue and went out of their way to declare the practice of religion—any religion—to be against the revolution.” The way he sees it, those arguing for a deep connection between Bolshevism and religion are presented with a conundrum that, by definition, cannot be solved: How can an intensely anti-religious movement possibly be considered religious in spirit?

“I would say that it all has to begin with the definition of what ‘secular religion’ is,” Michael Khodarkovsky, a historian and author of Russia’s Steppe Frontier: The Making of a Colonial Empire, 1500–1800, told me in an interview. “The Bolsheviks rejected any traditional religious faith but were fanatical idealogues who had their own set of beliefs. Does that make it a secular religion? Not for me, because religion implies the existence of a deity, and the Bolsheviks deified ideas, not superhuman entities.” For Khodarkovsky, the subjective experience of revolutionary struggle is not convincing or—at the very least—quantifiable enough to reasonably qualify Bolshevism as religious in character.

According to his detractors, Slezkine’s hypothesis also falls apart on closer inspection. In their review, Luehrmann and Weir accuse the author of cherry-picking his evidence, choosing “comparative cases so remote from the history of Bolshevism as to foreclose any investigations of mutual influence.” Instead of comparing the movement’s religious undertones to other Russian or even German socialist groups, or other faiths in the Russian Empire, like Catholicism or Judaism, Slezkine takes readers on a “transhistorical romp with stops at Mormon Utah, the Taiping rebellion, and the congregations of Apostle Paul,” hurting the believability of his argument in the process.

Most damningly, says Lohr, Slezkine fails to ascertain what separates Bolshevik millenarianism from other twentieth-century political trends. “You could make the same argument for any kind of extreme movement in the world. You could apply it to the Nazis, who also had an end point of history in mind, a vision of the end times.” The same, he adds, goes for Bolshevik co-opting of religious symbols and imagery. “All the liberal parties in Europe at the turn of the century co-opted religious aspects,” he explains. “The conservative parties co-opted them even more explicitly, perhaps, mainly for the reason that pretty much everyone who grew up in the nineteenth century was religious and raised in a religious context, so it’s not surprising to find that sort of language and symbolism as in political movements, even extremely anti-religious ones.”

Luehrmann and Weir further discredit the Bolshevism-as-secular-religion argument by looking at possible reasons for the argument’s emergence. Although introduced by Berdyaev, Lunacharsky, and other eyewitnesses to the October Revolution, this line of reasoning took off during the Cold War. This was for good reason, the two argue, as Western historians during that time “cast both ‘religion’ and ‘communism’ as irrational alternatives to liberal democracy and post-Fordist capitalism.”

Although looking at Bolshevism through a religious lens can help us see the movement in a new light, it also turns a blind eye to different viewpoints. Slezkine’s chapter on the impact of Russian literature, Luehrmann and Weir continue, “speaks to the role of fictional narratives in the Bolshevik experience” while leaving out other, more conventional and more plausible explanations for revolutionary action, such as “frustrated nationalism or social marginalization.” Slezkine rather conveniently glosses over the wealth of decidedly anti-religious golden age literature that spoke to young Bolsheviks. Even more important than Tolstoy’s oeuvre, for instance, was Nikolay Chernyshevsky’s 1863 novel What Is to Be Done?, about a woman whose quest for economic independence leads her to start a sewing cooperative. Though not up to the same literary standards as War and Peace or Anna Karenina, What Is to Be Done? inspired up-and-coming revolutionaries by painting a concrete picture of what a socialist utopia might look like.

Most influential of all was a minor character named Rakhmetov, a nobleman who—not unlike the prince of Tolstoy’s Resurrection—gives away his inheritance and travels across the country working various manual-labour jobs to “make himself loved and esteemed by the common people.” His passion for self-improvement and discipline, unconnected to the teachings of any religious creed, inspired several prominent revolutionaries. Imitating Rakhmetov, Lenin picked up weightlifting and swimming, while Sergey Nechayev, anarcho-communist and nihilist, slept on a bed of nails. In pre-revolutionary Russia, Rakhmetov quickly became the model for many young Bolsheviks.

Bolshevik thoughts on and legislation regarding the Russian Orthodox Church after the party’s 1917 coup further discredit the notion that Bolshevism was in any way inspired or indebted to Christianity, least of all its Slavic offspring. In The Oxford Handbook of Russian Religious Thought, Vera Shevzov, a historian of religion and a professor of Russian and East Asian studies, points out that Bolshevik leaders, far from finding inspiration in Orthodox doctrine, regarded the church as both an ally and an enabler of the late czarist regime. Upon seizing power, writes Shevzov, the Bolsheviks “not only homogenized Orthodoxy into the mix of ‘traditional faiths’—all pinpointed for eradication—but also relegated Orthodoxy to the position of least desired and most hazardous within that mix.”

Ultimately, says Lohr, scholars explore Bolshevism’s religious character to answer a much larger question: why Marxism succeeded in early twentieth-century Russia while in other countries during the same period it did not. “Berdyaev, himself somewhat of a Christian socialist, concluded that there was something about Russian culture that made it predisposed to this outcome.” Other observers agreed, but where they settled on the country’s long-standing tradition of autocracy—a tradition that continues to this day—or its unique location as a bridge between Europe and Asia, belonging to neither, Berdyaev believed the Soviet Union was born from the unlikely yet powerful union between European Marxism and Russian Orthodoxy.

For people like Lohr, this belief is difficult to stomach. “I tend to agree with historian Richard Pipes that, in the years leading up to the October Revolution, Orthodoxy didn’t have much of a theological side to it,” he contends. For most Russians, he explains, their age-old faith wasn’t a vehicle for rigorous scrutinization of human nature and the proper organization of society, the way it had been for, say, Tolstoy. Instead, it was routine, ritual: a servile but comforting adherence to commands and customs that went back further than the average villager knew or cared to remember.

Many Bolsheviks had an intensely private relationship to their political ideology—an ideology that, much like Orthodox Christianity, was equal parts idealistic and genuine, metaphysical and experiential.

“The apathy of the Russian population in the face of Bolshevik dominance is in part explained by the lack of a deep and vibrant theological tradition,” Lohr continues, “which is in stark contrast to Christian opposition to Marxist movements in Germany, where people actually died for their faith. The tragedy is that it was precisely at the turn of the twentieth century that the Russian Orthodox Church itself began to really become interested in the social dimensions of the gospel and get involved in Russians’ material lives. The church undertook a series of deep reforms in 1917 that might have really transformed the Orthodox Church, and there was a lot of excitement about returning to that series of discussions in the 1990s. Then, of course, the cretins running the Orthodox establishment crushed that hope and reapplied the older, pre-1900 tradition of cooperating and collaborating with the state.”

Both then and now, he argues, Orthodox traditions in Russia were fundamentally incompatible with Bolshevik revolutionary sentiment, preaching passive acceptance of the status quo and condemning any attempt to change the fabric of civilization.

At the same time, poetic passages like the ones written down by Arosev demonstrate that many Bolsheviks had an intensely private relationship to their political ideology—an ideology that, much like Orthodox Christianity, was equal parts idealistic and genuine, metaphysical and experiential. In the wake of the atrocities committed by Joseph Stalin and his immediate successors, it can be easy to forget that first-generation Bolsheviks like Arosev wholeheartedly believed in the validity, integrity, and benignity of their cause, and that this unwavering belief was as instrumental to their rise to power as any social, economic, or political conditions that bore witness to that rise.

Discussions of Bolshevism’s religious nature reveal that the definition of religion is itself contested. Lohr’s defining religion as requiring belief in a deity would exclude large segments of Buddhism and many Hindus, among other religious movements. If religion is defined, as some scholars do, as a collection of “beliefs and practices that generate social cohesion” and “orientation in life,” then Bolshevism could certainly be classified as a faith: a creed that filled its early followers with all-encompassing meaning and purpose to the same degree and emotional intensity that Orthodox Christianity served their pious forefathers. If the arguably religious nature of Bolshevism does not provide a definitive answer to the massive role this movement played in the twentieth century, it should at the very least be considered an important part of the puzzle.