T

I. Matter and Spirit

The first and most obvious answer to the question of my title is that the church is that funny-looking building on the corner.

That’s not a wholly wrong answer. A building, like a church, has an identity. It gets its identity from its walls. Walls separate. Walls distinguish. Walls discriminate. They are like the lines around a geometrical figure or the borders around a country or the definition of a term. Walls are physical lines, borders, or definitions. They distinguish “inside” from “outside.”

The church must discriminate. It cannot be another word for “here comes everybody.” In order for anyone to be “in” it, somebody has to be “out” of it.

But everybody knows that the church is also something more than a building. What is that? If you ask that question to anyone who considers himself to be “outside” rather than “inside” the church, you might get a second obvious answer, which psychologists might call a “functional” definition rather than a “structural” definition. It’s something like: “It’s where you do religious stuff, like praying and reading the Bible and singing religious music and listening to sermons—the church is for churchy stuff.”

Of course the first answer is too concrete and the second answer is too vague (as well as being circular). But there is something true in both of them.

Of course you should get a much better answer from someone “inside” than from someone “outside.” That’s true of almost everything. Lovers know love best, poets know poetry best, mathematicians know mathematics best, and comedians know comedy best (although only ponderous and scholarly philosophers with no sense of humour are allowed to write about that subject).

The only exceptions to the rule of “insider expertise” are evils, whether physical, psychological, or moral: the sober understand drunkenness better than drunks do, and the free understand any addiction better than addicts do. Saints understand sinners; sinners do not understand saints. The awake understand the sleeping; the sleeping do not understand the awake.

So what answer do you get if you ask someone who is “in” “the Church”?

You will certainly get an answer that is not as simple as our first two. That’s to be expected, and it’s not a bad thing. What may not be expected and what is a bad thing is that you will get different answers from different “churches,” and you will even get different answers from the same person. The Church is visible. The Church is invisible. The Church is “the Mystical Body of Christ.” The Church is “the people of God.” The Church is “the assembly of the faithful.” The Church is a “Magisterium,” a teaching authority. The Church is a spy operation, or a fishing operation, or a spiritual healing operation. The Church is the Ark of Salvation. The Church is a field hospital for sinners. The Church is a sheepfold. The Church is the Bride of Christ. The Church is the Whore of Babylon. The Church is “organized religion.” The Church is disorganized religion.

It would take a world-class theologian hundreds of pages to sort out and explain all those answers. I am not a world-class theologian. In fact I am not even a theologian, I’m a philosopher. And I don’t have hundreds of pages. So let’s start where the first and perhaps the greatest philosopher of all time, Socrates, started: by dialoging, by listening to ordinary people speaking ordinary language. And then let’s see where we can go from there: deeper and higher and clearer.

Our first popular and obvious answer was that the church is a building. Obviously that’s not adequate, but it’s a good starting point because it is clear and concrete. The structural walls of a building distinguish the “inside” from the “outside” in terms of space, and the activities that go on in that building distinguish the “sacred” from the “secular” in terms of time. Outside the walls of the church, space is “secular” or ordinary; inside is a “sacred” or “holy” space—or rather, a place (for “space” is an abstraction but a “place” is a reality).

“Sacred” means “holy,” which in turn means “set apart.” The very word “church” is a translation of ekklesia, which means “called-out.” There is a negative connotation here: called out from the secular, called to come out of secular places into this sacred place and out of secular time and into sacred time. There are no clocks in a church’s sanctuary. That’s why baseball is the most sacred game: It is the only major sport that does not measure its time by clocks.

But as Robert Frost wrote, “something there is that doesn’t love a wall.” Walls are “divisive.” That fear of walls is especially common in our egalitarian age, which is suspicious and envious of all hierarchy, all preferences, all “discrimination.” As Nietzsche observed about “The Last Man,” “Who wants to command? Who wants to obey? Both require too much exertion.”

This egalitarianism is quite in contrast and in conflict with the real universe. The universe is universally particular. Only abstractions like “humanity” or “justice” are universal. All men are created equal in their essence and in their natural rights and in their eternal value, but God made us diverse; that’s why he made more than one of us, beginning with Adam and Eve. Ontological egalitarianism is in conflict with God’s intentions in creating the universe; for each of the “days” of creation in Genesis is an act of discrimination: of being from non-being, of light from darkness, of day from night, of earth (“the waters below”) from the heavens (“the waters above”), of land from sea, of life from non-life, of animals from plants, of one species (“kind”) from another, of man from animal, of male from female, and, eventually, of moral good (trust and obey) from moral evil (doubt and disobey), of spiritual life from spiritual death, of heaven from hell.

Both of our first two popular answers to the question, What is the Church? instinctively understand that the Church creates a kind of hierarchy of the sacred over the secular, that it makes a difference, that it is a difference.

There is something profound in the child’s definition of the church as “that building.” It is much too narrow, of course, but it is concrete. There is also something profound in the vague feeling that the church is “you know, churchy stuff.” It is much too vague, of course, but it hints of mystery and moreness and transcendence; of a positive kind of indefinability. You don’t just see it (the building), you sort of smell it (the “churchiness”) or feel it or taste it. It is a “spirit,” not a thing. And yet it is also a “thing,” like a horse. You either get on it or not. If you do, it changes you. You are now a rider. You become something different, more like a centaur, half man and half horse.

From these crude but helpful beginnings we develop the two deeper and more theologically adequate ideas of

- the Church as a distinct, visible institution founded on this earth by the earthly Christ, at a particular time and place, in Jerusalem in the first century AD; as something like a Jacob’s ladder from earth to heaven; and

- the Church as an invisible spiritual organism, a supernatural mystery founded in heaven by the heavenly Christ; as something like a Jacob’s ladder from heaven to earth, the new Jerusalem descending from heaven, the bridal chamber for her marriage to the Lamb.

The tension between these two images is at the heart of the confusion. Is the Church a body or a soul? Is it a body that has a soul or a soul that has a body? (And is she an “it” or is it a “she”?)

This confusion about body and spirit (a confusion that has now also massively invaded our sexuality) is the same confusion we have had about ourselves ever since Descartes opened the Pandora’s box of his two “clear and distinct ideas” of body and spirit, or matter and mind. Matter takes up space and does not think; mind thinks and does not take up space. There is nothing common between these two ideas. They are indeed both clear and distinct. But we are not. We are confused.

How interesting that we are confused when we use clear and distinct ideas but we were not confused when we did not! We no longer think of ourselves as Aristotle and Aquinas did. Both of them said that the soul is the very “form” of the body and that the body was the very “matter” of the soul. “Form” meant not “shape” but “essence” or “essential nature” or “identity”; and “matter” meant not atoms and molecules” but “stuff” or “content” or “potentiality to be formed” by the soul. Body and soul are not two beings or entities but two dimensions of one being—man—much as the meaning of a book is its “form” and the words are its “matter.” To change either one of these two dimensions is always to change the other, and the only way to change either one is to change the other.

But we post-Cartesians are haunted by the spectre of “the ghost in the machine.” We think of ourselves as haunted houses rather than works of music whose spiritual beauty and meaning is its physical sounds, and whose sound is its beauty and meaning. The relation between those two is not causal but dimensional. Pascal had to remind us that we are “neither angel nor beast” because Descartes had split us into both, into a beast haunted by an angel and an angel trapped inside a beast.

Until our eyes are healed of these two cataracts of materialism and spiritualism, or (to change the image) until we see with both eyes at once, we will not have life in the Church, for the separation of body and soul is the definition of death, not life.

Our new, Cartesian, anthropology is closely connected with our new ecclesial situation. It is no accident that Descartes’s new anthropology emerged in the century after the Protestant Reformation, which was a “spiritualistic,” neo-Gnostic protest against Catholic “pagan, materialistic” sacramentalism, which was seen as superstition, and as an antinomian protest in the name of spiritual (and political) freedom against Catholic moral authoritarianism and “legalism.” In fact, the Church is both visible and invisible. Like us. It is equally true that the Church is “the body of Christ” and that the Holy Spirit is “the soul of the Church.” The Church is not a holy house haunted by a holy ghost. Until we understand this instinctively, until our eyes are healed of these two cataracts of materialism and spiritualism, or (to change the image) until we see with both eyes at once, we will not have life in the Church, for the separation of body and soul is the definition of death, not life.

The Holy Spirit is “the soul of the Church” so the Church is “spiritual.” But that does not mean it is abstract, a set of values or creeds or codes. The Holy Spirit is not an “it” but a “he.” He is a divine Person. He is the Spirit of the unincarnate Father, which is emphasized by the more mystically “spiritual” Eastern Orthodox. And he is also the Spirit of Christ, which is emphasized by Christocentric evangelical Protestants. And he is also the Spirit of the Father and the Son together in love, which is the point of the filioque clause, which was added by the Roman Catholic Church. Perhaps if the churches came together theologically on the Holy Spirit they could come together ecclesiastically and visibly too.

II. Ecumenism

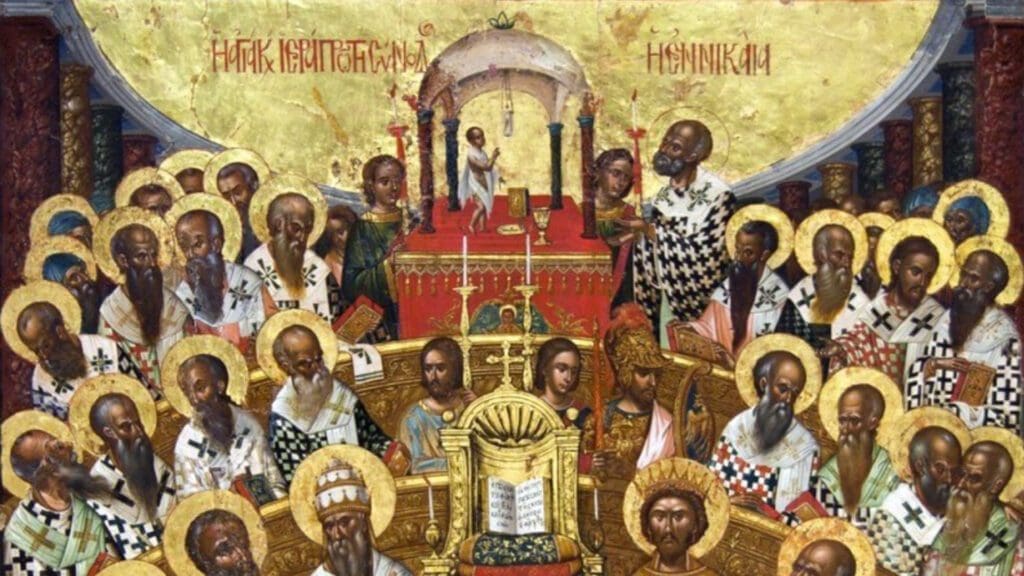

This brings up the inevitable and embarrassing fact that we have been at war with ourselves ever since 1054 and 1917. We’ve been losing the world war ever since we started fighting our civil war. The seamless garment that covered Christ’s body has been torn into shreds. What his enemies, the Romans who crucified him, did not do his own disciples did. We dismembered his body.

Following on our first point about the need to join the visible and invisible dimensions of the Church together more totally, our next point is the need to rejoin the churches and their “specialties,” their “contributions,” their charisms or supernatural gifts, together in a single visible body. For to Protestant eyes the visible Church, both Eastern (Orthodox) and Western (Roman Catholic) looks like a fireplace without much of a fire; and to Catholic eyes the Protestant and Pentecostal and nondenominational critics of the visible Church, who emphasize the “invisible Church,” look like a fire without much of a fireplace.

Our problem is painfully obvious, and I will not take the time to repeat what we already know, except very briefly. Let me list seven points about ecumenical relations that I think are so obvious that all Christians of goodwill agree to them.

- Obviously, the Church is both visible and invisible, both fireplace and fire, both body and soul. Neither can live without the other.

- Equally obvious is the fact that our disunity is a tragedy and a travesty. It is also a sacrilege, for its victim (the Church) is sacred. We are “members” of Christ not as individuals are members of an organization but as organs are “members” of an organism. We have dismembered Christ’s body; and since that body is just as real as his individual physical body, it is as grotesque as chopping off his arms and legs. It also dismembers our witness to the world, and makes Christ’s prediction that “by this will they know that you are my disciples: by the love you have for one another” into a cynical and ironic joke. It is a tremendous victory for the devil, for the single most effective principle of military strategy, whether the war is spiritual or material, is to “divide and conquer.” It also makes Christ a polygamist. When he comes again, will he marry a harem?

- Of equal obviousness is the fact that the solution to the problem of our divisions is not obvious. In fact it seems impossible, for it is about truth, and truth cannot be compromised. “With God all things are possible,” but violations of the law of non-contradiction are not possible even for God, because they are not things at all, they are nothings. Meaninglessness does not magically turn into meaning when we add the words “God can do this.”

- One other thing that is obvious is that we all need to listen better to each other—“better” meaning more coolly and open-mindedly and honestly and humbly, and at the same time with more heat and fire and love and passion. And that we need to do this with the right primary motive: not primarily for the sake of reunion but for the sake of truth and to fulfill the will of our Lord.

- It is also fairly obvious that we should begin with, and focus on, what we already agree on, the positive things, as the foundation for dealing with what we do not agree on. It is equally obvious that we cannot ignore our disagreements and that we must view our disagreements in light of our agreements, not vice versa.

- It is also obvious that we must identify and remove the obstacles that impede our task; and that those obstacles include both moral and intellectual sins, on all sides. Among our moral sins are our cowardice, our lust for approval, and for the pleasure and self-satisfaction of superiority and victory over our rivals. And sometimes also the opposite, subtler errors: our recklessness, our masochistic lust to be condemned and rejected so that we can play the self-satisfying role of martyr.

- The single most important way to overcome our tragic divisions is also obvious in principle but far from obvious in practice: insofar as we surrender and submit to the will of God, insofar as we follow the baton of the one Conductor of our large and squabbling orchestra, we will play in harmony (though not in unison), for we know that harmony is his will, and therefore our disharmonies all stem from our disobedient wills.

But our wills follow our minds—we can will only what we understand, or think we understand—and our minds sincerely differ about what is true. That is the basis of the problem. And the basis of the solution is that the mind follows the will as well as the will following the mind. And this gives us an opening, a hope.

St. Thomas says that although the will always follows the mind as the “pull” of its final cause, it is also true that the will moves the mind as an efficient cause, as a “push.” Jesus implied that when he said to his critics who asked him how they could understand his teaching and how they could know it was from God: “If your will were to do the will of my Father, you would understand my teaching, that it is from him” (John 7:17). Hearts and wills can educate minds as well as vice versa. As Pascal says, the heart has reasons; it has an eye in it. Thus we need to purify our hearts, our wills, our intentions, our loves, in order to purify and clarify our minds.

But this makes things harder rather than easier, for it means that the way to the high and holy, difficult and demanding goal of understanding each other so as to overcome our disagreements is something that is in itself even higher and holier, more difficult and demanding: to become saints.

But it is just here, in what seems to be the hardest requirement, that we find hope. For there are great saints in all the churches. We have spent much time and effort in sincerely listening to each other’s theologians; perhaps we should spend more time and effort in sincerely listening to each other’s saints.

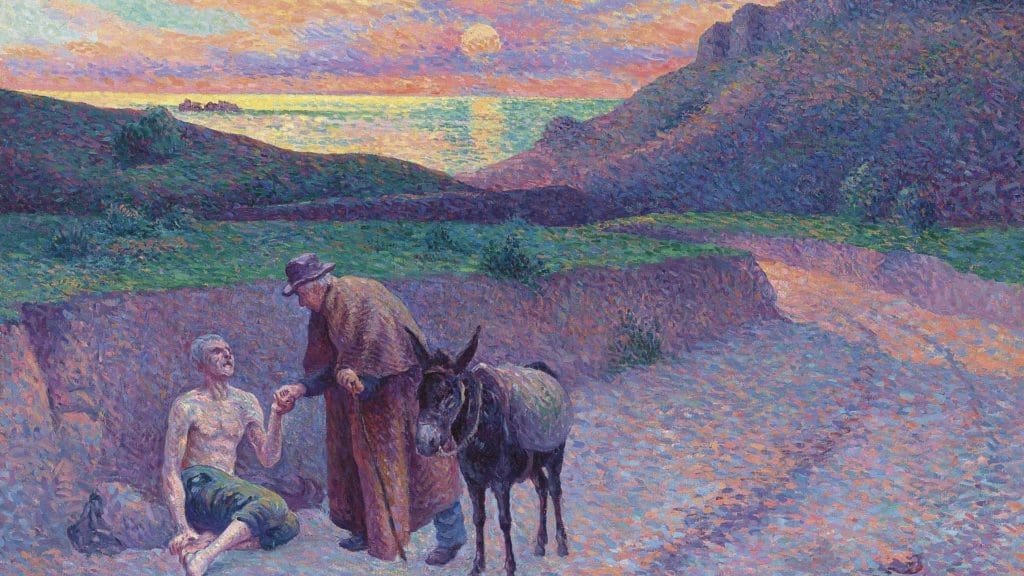

Honest and faithful Catholics and Orthodox must admit that the heretics are often more saintly than the orthodox. Universalists, Black Baptists, Quakers, the Bruderhof, Pentecostals, those who are the farthest from and the most suspicious of Catholic theology, liturgy, and ecclesiology—these are some of the most saintly. (If you doubt that, just listen. Those birds can sing!)

Rather than speculate about what bad causes produce the bad effect of heresy, let’s ask what good effects could come from the sanctity of the heretics. What would happen if we listened to them? What would happen to them if they listened to our saints? (They already do that to us much more than we do it to them.)

Two effects would result from this cause. The first effect is obvious and clear and certain and well known and not controversial; the second is the opposite. The first effect is that we (and they) would be inspired and inflamed to love and serve and obey our common Lord much more totally and completely and selflessly and passionately and effectively. Our persons and our lives would be significantly changed. And the second effect would be that since our persons and our lives as a whole would be changed, and since our minds are an essential dimension of our persons and our lives, therefore our minds would be changed too.

How?

In ways that we do not yet understand, for they have not been changed yet!

So let’s exchange preachers. Let’s listen to each other’s most inspiring teachers in our church services and our retreats and conferences.

But we must listen with the right motive. The right motive is not primarily to understand our opponents’ theology or their complaints, good as that motive is. The right motive is also not primarily to solve the ecumenical problem, the problem of disunity, though that is a very good motive too. But there is something much better and prior. Let us listen with the simple intention of becoming more saintly, more Christlike, more in love with and in the service of our common Lord.

So these speakers and preachers and teachers should not be theologians and apologists, controversialists and debaters, necessary and honest as these enterprises are and absolute as the will to truth is. Nor would they be sociologists and psychologists and “facilitators” who ignore our distinctive differences in order to unite us; “people persons” whose job is to “bring people together.” The first kind of teachers change minds without changing hearts, and the second kind change hearts without changing minds. The first kind specialize in truth and tend to bracket love; the second kind specialize in love and tend to bracket truth. We need more. We need a unity of head and heart. We need a unity of our own organs before we attain the unity of our churches.

That’s certainly far from an adequate solution, but it’s a beginning. As the ancient Greeks sagely said, “Well begun is half done.”

III. Threes

To be complete as the Church, and to be complete in our ecumenical enterprises as described above, we need to strengthen all three of the fundamental dimensions of the Church. These correspond to the three fundamental distinctively human powers of our own human nature, which is the nature that Church is divinely designed for: the will, the mind, and the heart.

It is the mind that knows the truth. It is will that chooses the good. And it is the heart that loves the lovely and the beautiful and the joyful.

This three-faculty psychology is common sense, and is common to thinkers as diverse as Plato and Freud. These are the three things we all seek without limit: truth, goodness, and beauty. These distinguish us from the beasts. They are the heart of every human civilization and culture.

Thus every religion has a creed, a code, and a cult (or a culture); words, works, and worship both private and public; a theology, a morality, and a liturgy, or a “spirituality.”

Thus God instituted three offices and ordained three office-holders in his first Church, ancient Israel: prophets, kings, and priests.

Thus our great epics typically have three heroes, three protagonists: Gandalf, Aragorn, and Frodo in The Lord of the Rings; Ivan, Dmitri, and Alyosha in The Brothers Karamazov; Hooper, Quint, and Brodie in Jaws; Spock, Captain Kirk, and Bones McCoy in Star Trek; and John, Peter, and James in the New Testament.

Thus the East has three great cultures: India, which specializes in mystical wisdom and contemplation; China, which specializes in practical moral and political living, whether Confucian, Taoist, or Communist; and Japan, which specializes in art and beauty. Of course these are great oversimplifications, but so are road maps and the rules of grammar.

And among the churches, Protestants are the most propositional and biblical and creedal (that’s why they split into thirty thousand denominations), Catholics are the most moral and practical and legal and political, and the Eastern Orthodox are the most mystically beautiful and liturgical.

These are proper “specializations” and not in themselves a cause of division. What is a cause of division is differences in creeds, not in codes or cults.

Not differences in codes because there are none. The natural moral law is known to all. And all the world’s religions have very similar and very high moral demands for displacing the selfish ego and practicing the universally known virtues of charity, justice, mercy, compassion, understanding, honesty, humility, courage, self-control, and wisdom.

Nor are differences in cults a cause of division because they are a glory, not a scandal. Each religion already has a diversity of cultic practices. Theories, philosophies, and ideologies rival each other as contradictory claims to truth, but arts and practices that embody spiritual beauty do not rival each other.

Since it is creeds that divide, many would-be “reuniters” ignore, downplay, deny, or denounce creeds. But this is to ignore one of the three essential dimensions of human nature and of religion.

Our civilization seems simultaneously irrationalistic and rationalistic. The seesaw extremes reinforce each other. We academics, who tend to rationalism, usually assume that creedal differences must be our starting point and focus. But perhaps we should look first at what people do in fact usually begin with, which is the third of the three dimensions we have distinguished—namely, the heart, and love, and the search for joy. Beauty is the ambassador for truth and goodness; we fall in love with the beauty of a theology or of a morality first—and the same is true of a religion.

Perhaps the primary cause of the decline of religion in Western civilization is not its lack of theology (and truth) or its morality (and goodness) but its art (and beauty). Christianity no longer moves our hearts because it no longer moves our arts. Our pictures are not moving pictures. They are still shots. And they are in black and white.

The Church should fire half its bureaucrats and employ artists instead.

Our culture is ripe for aesthetic evangelization. It is a culture of robots. An overwhelming percentage of our educational investments are in the STEM courses, while the arts and the humanities are dying. One more Shakespeare, one more T.S. Eliot, one more Tolkien, one more Bach, one more Rembrandt, one more Dostoevsky, one more Notre Dame cathedral might bring us “farther up and farther in” than anything else. This is a crucial mission field. The Church should fire half its bureaucrats and employ artists instead. No one was ever converted by a committee, but many lives were changed by music. Damon of Athens said, “Let me write the songs of a nation and I care not who writes its laws.” We should have not just missionaries of truth and of goodness but also of beauty; not just of wisdom and of works but of wonder. For wonder is the beginning of all wisdom, and wisdom is the beginning of all good works.

IV. What’s New?

What’s new today for the Church to think and act about is not the COVID-19 lockdown. That’s not radically new. There have been pandemics before, and there will be pandemics again. This one only changed the placement of a few billion bodies from the streets back into the homes (and that was only temporary) and the placement of a few trillion dollars, which is a triviality compared to changing the placement of eternal souls. Let’s not commit the fallacy of the traveller in the passenger seat: always seeing the nearest telephone pole along the road as the one that is looming largest and most important. Largeness is not produced by looming. As the saying goes, “He who marries the spirit of the times will very soon become a widower.”

But there is something genuinely new in the world that needs a new response from the Church. It is the phenomenon of the single fastest growing religion in the world, which is not Christianity or Islam but the religion of irreligion, of indifference, of “whatever.”

It is not a return to paganism. That would be progress. Paganism was religious. Paganism was convertible. Paganism was marriageable. Paganism was a virgin; Christendom was a married woman; modernity is a divorcee. A divorcee does not go back to being a virgin.

They are winning. We are losing. Ten times more people exit the Church than enter it in most countries in Europe, and six times more in America. The situation has been turned upside down. We are now the threatening outsiders, the barbarians at the gates. The barbarians long ago entered the city and control the universities and the media.

This is a new opportunity. Every other revolution has become old; we the Church are the only answer to “what’s new?” We not only have the goods, we have the good news. Every other revolution has become part of the establishment, and the only radical revolution left is orthodoxy.

In this “new age” we need a “new evangelization,” but not because there is a new “evangel” but because there is a new “ization,” a new need and a new audience.

The new need is the spiritual vacuum, the nihilism. All nature abhors a vacuum, and that is true of the nature of spirit as well as the nature of space. The human heart was designed in heaven, not in Harvard or Hollywood, and it cannot find what it seeks, what it cannot help seeking—namely, true and deep and lasting joy—in any of its idols. The worse the world gets, the better our chances for converting it are because the better our product looks by comparison. Thus Walker Percy’s four-word answer to the question: “Why are you a Catholic?” “What else is there?”

The new evangelization has not only a new need but also a new audience, both inside and outside the Church.

Inside first. The Church herself needs to be evangelized first. FOCUS, an organization of young Catholic missionaries, is targeting the most desperately needy spiritual slums in the world, as missionaries have always done. Their mission field is . . . universities, especially Catholic universities!

Let’s disobey our modern prophets, our pop psychologists, and trust ourselves less, not more.

Outside the church our audience is also new: it is a culture that is going literally insane with its postmodern philosophy of absolute relativism, a culture that officially tells God to “get out of my seat” because it is we who have the freedom and the right and the power to create our own identity, to determine the meaning of life and the mystery of existence. This is “at the heart of liberty” according to the authority we court, our Supreme Court authority. We are already more than halfway to Brave New World and what C.S. Lewis called “the abolition of Man.” We have a new human nature because we have performed radical surgery on ourselves: a conscience-ectomy. That operation is paired with the replacement of the brain with the sex organ, and with turning the human frame upside down so that we can walk with our nose to the grindstone, our eyes to the earth, and our feet kicking up in rebellion against the heavens.

How should we respond to all this, then? I have no complete or complex program, but I have eight starting but not startling suggestions.

- Let’s try beginning with saints. Let’s listen to each other’s saints.

- Let’s try beginning with beauty. Let’s make that our mission field.

- Let’s evangelize ourselves first. Let’s follow FOCUS.

- Let’s attack at what seems to be the culture’s strongest point but is really its weakest point: its supposedly new but really tiresomely old philosophy of the right to sexual happiness no matter what—which is its weakness because in practice it always leads to misery, while the Church’s response to the sexual revolution in John Paul II’s theology of the body is in fact the true sexual revolution and in practice always leads to joy.

- Let’s not get caught up in the social mania of social media, even as we rely increasingly on them during our “social distancing.” Let’s not substitute the virtual for the virtuous. The Church is “the extension of the incarnation,” not the supernatural internet or the Matrix. It’s made of people, not pixels. I think the most universal object of addiction today, especially among children, is not alcohol or drugs or even sex but the smartphone. It is literally impossible for them to live without it. Down with idols, whether sexual or technological!

- Our new technologies give us great powers that we never had before. But they also leave us individually weaker than ever before. We are like quadriplegics with prosthetic limbs, butterflies in Iron Man space suits, the little liar behind the scary screen in The Wizard of Oz. So let’s fast from our “will to power.” Let’s restore concepts like “holy poverty” and “sacrifice” and “detachment” and “abandonment to divine providence.” When the Church was poor, she was rich; when she got rich, she got poor. Where is the Church the weakest today? In what used to be called Christendom, where she is the richest and the strongest. Where is she the strongest? In Africa, where she is the poorest.

- Let’s disobey our modern prophets, our pop psychologists, and trust ourselves less, not more. Let’s learn from the Muslims, who remind themselves five times every day that “only God is God.” He alone can convert hearts and save the world. Let’s stop those idolatrous liturgies of self-celebration.

- When his primitive church (the apostles) could not exorcise a demon, Christ said, “This kind comes out only by prayer and fasting.” So let’s pray. (Now, not later!) And let’s fast. Not just from food but from comfort-mongering and security-mongering. Let’s embrace the cross, because that’s where we find Christ. Fulton Sheen used to say that Communism is the cross without Christ and American Christianity is Christ without the cross, and neither one of those can win a world that lacks both.

Finally, what is the Church? The Church is not a thing like an orange out of which we can squeeze Christ like orange juice. Nor is the Church the orange juice and Christ the orange. They are not two things; they are one. Where Christ is the Church is, and where the Church is Christ is. It is his body. Where I am my body is, and where my body is I am. When Joan of Arc was questioned by unbelieving bishops who tried to confuse her by driving a wedge between her visions of Christ and their churchly authority, she responded, “I don’t know how to answer your questions. I just know that Christ and his Church are one thing, not two.”

There is no other possible way to revitalize the Church than to revitalize our personal relationship to Christ. It is equally true that there is no other possible way to revitalize our personal relationship to Christ than to revitalize our membership and participation in his Church. So what does this mean in practice? I will begin with a single very specific suggestion. As soon as the authorities and the virus allow, let us resolve to adore Christ in the Eucharist regularly, religiously.

No individual and no parish that did that ever failed to experience transformation. For when you practice his presence, when you expose yourself to his Lordship and loveship, when you pray and mean with an honest heart, “Thy will be done,” when you say Mary’s word of real magic, fiat, then it is guaranteed, by divine and infallible authority, that he will answer, and his will will be done, and if you are unwise you will duck, and if you are wise you will ride that wave.