C

Christopher Watkin has written a book called Biblical Critical Theory. For many readers, these three words will prove a puzzle. Placed next to one another, they make for strange bedfellows. Before unpacking the whole phrase, however, we need to understand the original term being modified by “biblical.”

Critical theory names a family of analytical tools that unveil, expose, or unmask the hidden wrongs of our common life. For critical theory, there is always a man—a force, a system, a power—behind the curtain that we call truth, morality, or beauty. For the more drastic critical theorists, civilization is nothing but curtains. Living in Oz means the task of theory is endless. The aim of criticism may be justice, but such justice will inevitably contain new injustice, and so generate ever further criticism.

This may sound cynical. But we ought to pause before rejecting such a view out of hand. Jews and Christians were primal practitioners of “apocalypse,” a potent and rather spectacular form of revealing unjust systems at work in the visible everyday structures of society. God’s people were bold enough to claim to see behind and beyond and above the ruling authorities of their day—whether Babylon, Persia, Greece, or Rome—and what they saw was monstrous: empires built on slaves, regimes bathed in blood, temples built to demons, peace bought with war. Pagans returned the favour. They saw Christians as anarchic, atheist, uncivil, sectarian, and unduly pessimistic about human nature. Not unlike the way many view critical theorists today.

Indeed, the church is committed to the most radical of all critical theories—namely, original sin. No philosophy is more honest about the human capacity for evil and self-deception than St. Augustine and John Calvin. Every secular attempt to outdo the Christian doctrine of sin is bound to fail. It can never go far enough or deep enough. From conception, you and I and every other human being in history are sinful through and through. As Ian McFarland puts it, we are not sinners because we sin; we sin because we are sinners. And by our own efforts, there is nothing we can do about it. The harder we squirm in the quicksand, the deeper and faster we sink.

The question is not how to destroy critical theory, but how to disentangle the good from the bad.

As for postmodern critical theory, like so much else in Western thought its roots lie in Christianity itself. It is less heathen than heresy. It is a branch shorn from the tree, not an alien or poisonous vine. It has wisdom to offer alongside distorted or corrupted ideas. The question, then, is not how to destroy it, but how to disentangle the good from the bad. More to the point, the question is how the church might do it one better, by formulating her own critical theory—the substance of which secular theory is the shadow.

A number of theologians and philosophers have sought to do just that in recent decades, chief among them Alasdair MacIntyre, Charles Taylor, John Milbank, and David Bentley Hart. Another name to add is Robert Jenson, who wrote the following in 1999, regarding the dangers of theologians borrowing from social theory to describe the church:

The church is not simply heaven, describable in this age only in the imagery of apocalyptic; but neither is she simply a phenomenon of this age, patient of the concepts and hypotheses of secular social theory. Therefore, at least with respect to the church herself, “theology . . . will have to provide its own account of the final causes at work in human history.” Borrowings from secular theory may sometimes be convenient but must be done strictly ad hoc and with great circumspection and usually . . . with considerable bending of the recruited concepts.

Why this circumspection? Partly because the church is a unique institution in the world: at once heavenly and earthly, eternal and temporal. More important, though, it is because “the successive modes of Western social theory are a succession of Christian heresies and so necessarily distort reality,” as Jenson paraphrases Milbank’s thesis. The church needs her own theory, proper to the gospel and therefore to reality in light of the gospel, if she would truly penetrate the depths of mere phenomenal and social perception. We need God’s eyes to see God’s world truly.

The church’s response to the challenges of modernity and postmodernity cannot be to play by their rules, on their terms. It must be a genuinely spiritual and theological response, rooted in the good news of Jesus.

Jenson goes on to write that “the needed social theory is and can only be the doctrine of Trinity itself.” Whether or not Jenson is right about that, his approach is exemplary. The church’s response to the challenges of modernity and postmodernity cannot be to play by their rules, on their terms. It must be a genuinely spiritual and theological response, rooted in the good news of Jesus. This means, in turn, the church’s theory must be sourced and governed by Holy Scripture. Above all, it means following the example of Augustine in his magisterial work The City of God, written in the early fifth century. There the bishop of Hippo sets forth competing narrations: the course of the earthly city, defined by love of self, running in parallel with the pilgrimage of the heavenly city, defined by love of God. Whereas the former is bound for destruction, the latter is destined for glory. These twinned stories constitute the one history of the world; accordingly, Augustine leaves nothing out: philosophy, sacrifice, war, slavery, language, sex, bodies, souls, political order—and much more. Every Christian bid to out-narrate pagan or heretical accounts of human life is an imitation of Augustine’s paradigmatic project. It is doubtful anyone will ever match his achievement. But it will always remain the measure of such attempts.

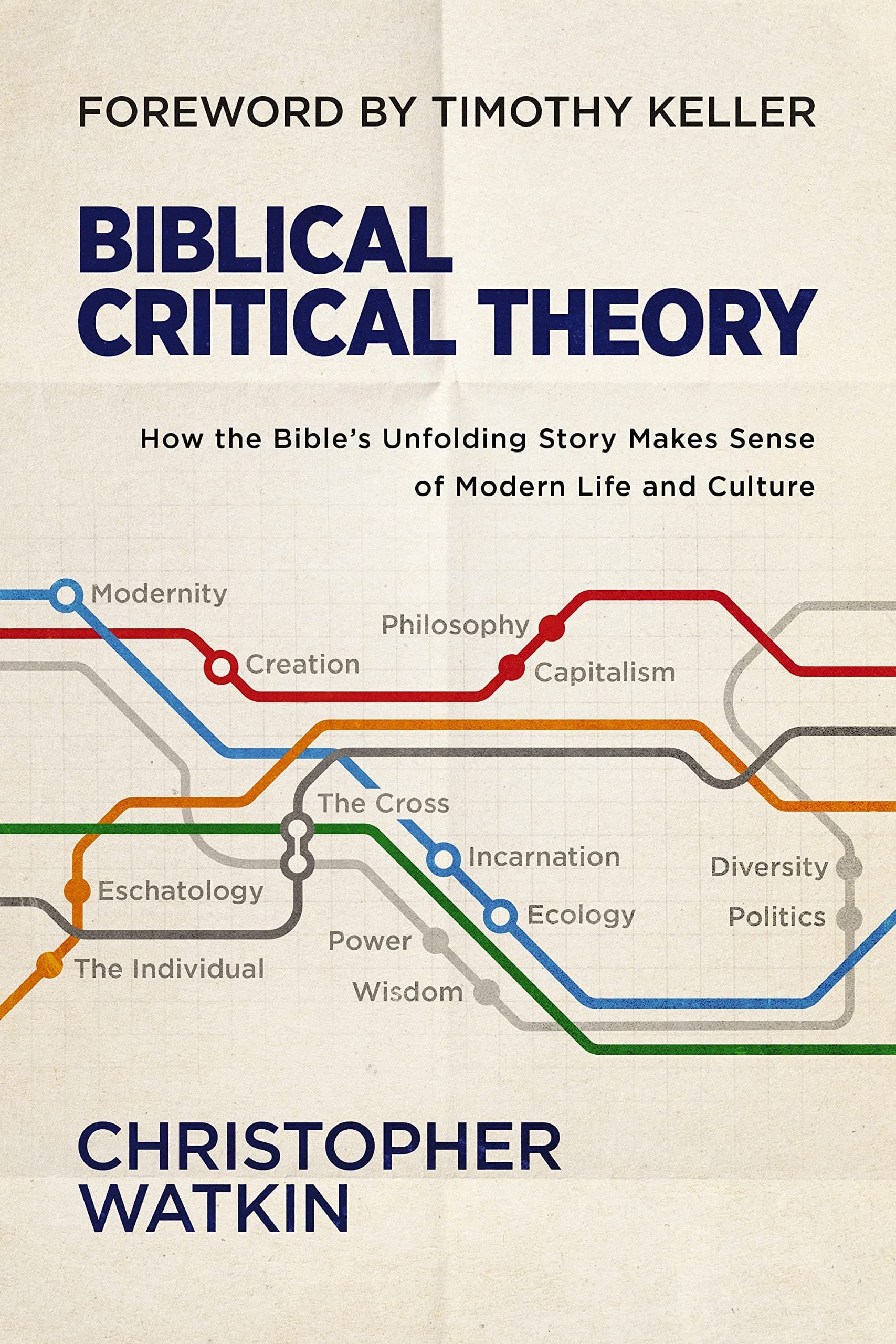

Watkin’s new book is the latest attempt. Its subtitle lays out the aim and scope of the work: How the Bible’s Unfolding Story Makes Sense of Modern Life and Culture. Watkin is a scholar of modern and postmodern French and German philosophy. He has written a number of studies on major contemporary theorists like Derrida, Foucault, Deleuze, and Serres. He earned his doctorate at Cambridge and teaches in Melbourne. This is not his first book for a popular audience, but it is certainly his biggest and boldest. Running more than six hundred pages and spanning the entire biblical narrative, the book closely follows the Augustinian blueprint. Watkin wrote the work he sought but couldn’t find in the library stacks: a biblical critical theory, in careful conversation with and counterpoint to the variety of secular critical theories on offer. Each of the scholars I mentioned above (MacIntyre et al.) is catholic in one form or another. Watkin saw this gap in the literature: an evangelical Protestant meta-response to (post)modernity. So he took up the task himself.

Here is how he describes the project:

A biblical social and cultural theory is both possible and important today if we are to refresh the agenda for Christian cultural engagement in our generation, as we must in every generation. But there is also a sense in which a biblical social theory should be radically different from other social theories. It is not just like critical theory or feminist theory with different labels. Reflecting the patterns and rhythms of the Bible itself, a biblical social theory should be distinct not simply in its content but in its manner and mode of engagement. . . .

In The City of God Augustine does not merely explain the Bible to Roman culture, he explains Roman culture within the framework of the biblical story. In other words, he elaborates a biblical social and cultural theory for his day. At our own moment in history it is not enough for Christians to explain the Bible to our culture. We must explain our culture through the Bible as we pray for the raising up of a generation of thoroughly Christian social theorists.

This quote is representative of the flavour of Watkin’s writing. Congenial, patient, pious, and thoughtful, his prose is disposed against polemic, indictment, and the rhetoric of culture war. Augustine is never far from his mind; neither are Taylor, Milbank, and Hart. He has his own unique approach, though. Here are the main features.

First, Watkin wants to place the Bible front and centre as itself a, or the, principal tool of social analysis, cultural critique, and spiritual converse. This underwrites, second, an emphasis on “Christianity at its best, the Christianity of Christ”; the book is therefore “about biblical figures, not primarily about flawed and sinful people.” Third, with Christ at the centre, the resulting mode or temper of intellectual engagement is winsome. Charity for God, neighbour, and culture alike is definitive of the life to which Christ calls his followers; encounters with opponents, however hostile or wicked they may be, should thus be charitable and in good faith. The necessary accompanying posture, fourth, is “nonpartisan.” Watkin has an allergy to Western cultures’ constant demand to take sides; his desire instead is to grasp the “worlds” of the societies we inhabit in all their complexity through examining the “figures” that constitute them and sifting the wheat from the chaff.

“Figure” here is a term of art intended “to embrace all the patterns and rhythms that shape our lives.” Watkin sets the “figures” of the biblical world alongside those of the fallen world in order to show how the first embrace, fulfill, and/or call into question the second. Watkin selects this word for its capacity to capture the totality of a culture’s lived reality, in all that it says and does and all that it takes for granted; in other approaches to “Christianity and culture” he sees an unnecessarily narrow focus on the cognitive, the symbolic, the behavioural, or the material.

The book’s fifth and final distinctive feature is the sum of the rest: what Watkin calls “diagonalization.” This procedure recurs in every chapter of the book. Put simply, it is a refusal to accept false binaries and to opt instead for a third way. Watkin insists that this method is not a trite via media, balanced evenly between every worldly dichotomy. Rather, it rejoins what sin has fractured: not a mean or a median, but a repair, a surgical operation, even a transfiguration. As he writes, “the aim of this book is not to offer piecemeal arguments on this or that burning issue but to unfold a connected story that diagonalizes dominant contemporary cultural alternatives. In other words, rather than either brushing away modern cultural figures or falling into lockstep with them, the task of out-narrating is a way of allowing the Bible to diagnose and heal them, fulfilling all that is good in them and everything that makes for flourishing.”

From Genesis to Revelation, Watkin renders the canonical story as simultaneously a judgment on Western society and an alternative to it; its primordial source and ultimate fulfillment. In the Bible he proposes to find an untapped resource for cultural criticism, even a full-blown critical theory.

Does he succeed? For all the erudition, wisdom, and guileless faith on offer in the book, I do not think he does. In what follows I explain why.

Watkin has done his homework. No reader will doubt that. His expertise shines through most clearly when he is on his “home turf,” interpreting Latour or Heidegger or Riceour or one of their many peers. His sympathy for their ideas, his handling of their often impenetrable prose, his ability to render their thought into words accessible to ordinary Christians—these are his greatest gifts. Many pastors and lay believers will benefit from Watkin’s labours to demystify and expound these authors, their texts, and their ideas.

The problem is not that Watkin presents us with straw men, though at times certain ideas are so simplified as to appear that way. No, the problem lies with his solutions. These are consistently banal, platitudinous, and even vacuous. His “diagonalizations” amount either to sheer assertions or to “third ways” any reasonable person (Christian or not) would affirm.

Take an early example from the book. In his chapter on the creation account in Genesis 1, Watkin pauses to discuss the fact-value dichotomy. He mentions the “long and tortuous genealogy that takes us from Aristotle via the medieval nominalists, voluntarists, Kant and Kierkegaard, up to the ‘postmodern’ thinkers,” a line of thought that arrives at a notion many of us take for granted: “facts” are “public and universal” and “values” are “private and subjective.” It is a fact, on this scheme, that the earth is round, but a value that adultery is wrong. Yet there is something amiss here. Adultery has public purchase, in law and custom and childrearing, whereas awareness of the roundness of the earth doesn’t much affect the way I live day to day. Humans got along well enough for a long time without the knowledge of that “fact,” important as it is. We can barely last a generation without the “value.”

His “diagonalizations” amount either to sheer assertions or to “third ways” any reasonable person (Christian or not) would affirm.

Watkin is right, therefore, to draw attention to this false division. He follows up his reference to its genealogy with this comment: “The Bible, by contrast, resists attempts to wrench facts and values apart. We could say that for the Bible, values are factual and facts are valuable.” And after a few more sentences, he moves on to the next topic. The whole subsection takes less than a page.

The brevity and superficiality on display here are representative. What could the import of such a discussion be? Is it intended to persuade? Is the reader supposed to conclude that the Bible, just as it stands—perhaps its opening chapter alone—resolves a centuries-long conundrum in philosophy? Are we to take Watkin’s word for it? The suggestion is neither exegesis nor argument; it is a premise expressed as a conclusion. It is true that Christians need not accept the modern dichotomy of facts and values. I fail to see, though, how readers are helped by a treatment as perfunctory and assertive as this.

Now consider some other dichotomies that Watkin “diagonalizes”: “loveless justice” versus “justiceless love”; traditional versus modern societies; “No human improvement is permitted” versus “Any and every human ‘improvement’ is permitted”; rationalism versus irrationalism; nature/determinism/appetite versus freedom/self-determination/reason; faith versus reason; Brexiteers versus Remainers (!); cynicism versus idealism; liberal versus conservative; assimilation versus isolation; political radicalism versus political compromise; “evolutionary progress” versus “revolutionary transformation”; and many, many more.

If anything is deserving of the kind of opprobrium directed in recent years at “both-sides-ism” and “third-way-ism,” it is this list. Invariably Watkin presents two ideal types, bordering on caricature, that stand on each side of a cultural divide, and “the Bible” is there to guide us smoothly between Scylla and Charybdis.

The trouble is twofold. On one hand, there are no teeth to Watkin’s “diagonalizing” proposals. Take Brexit, his own example. Following Graham Tomlin, bishop of Kensington, Watkin claims that “the Brexit debate . . . divided and opposed the two natures of Christ.” Whereas Remainers were attached to the universal, Brexiteers were attached to the particular. His proposed diagonalization? Four words: The Word became flesh. As he elaborates: “The tragedy of the Brexit saga was that it forced us to choose between these two sets of values, when the very distinction and opposition between them is already a heretical dismembering of a more complex incarnational view in which they are perfectly united.”

I don’t want to mince words. As a matter of analysis, this is hackneyed and hollow; as a program for practical action, it is useless. For anyone responsible for voting on the question or executing the decision, this “critical theory” would offer neither guidance nor understanding. At best, you would have Christians who utterly disagreed with each other about Brexit who nevertheless agreed in principle that the particular (Christ’s human nature) and the universal (Christ’s divine nature) are not opposed but united. So what?

On the other hand, the actual sides represented here would not recognize themselves in Watkin’s portrayal. There were and are advocates of Brexit who could be called on to offer a nuanced defence of the decision to leave the European Union, a defence in no way implicated by racism or sneering parochialism. But Watkin’s reader wouldn’t know it. We don’t hear from such a perspective. We are left with brief generic summaries painted in broad brush strokes, little more.

The result, across the book, is an essentially idealist engagement with contemporary society and its mores. It is idealist in the sense that it rarely, if ever, leaves the realm of ideas to touch down on terra firma; and in the sense that it pits biblical ideals against ideal types of the finite, imperfect, fallen world as it is. Hardly a fair fight, I’d say. In one way this amounts to a continuous comparison of apples and oranges. In another way it leaves everything just as it was. After all, the Brexit vote was a binary choice, and in the voting booth, Watkin’s theory offers no direction. What is a Christian to do when faced with only two options?

Watkin proposes diagonalization as a finely honed tool of spiritual surgery, “cutting across and rearranging false cultural dichotomies.” Yet it fails to deliver in practice. In Watkin’s hands it proves less a scalpel than a cudgel.

But the book has deeper problems than these, problems rooted in prior decisions on Watkin’s part.

First is his choice to construct a biblical rather than a Christian or ecclesial or theological critical theory. The Bible is many things, but it is not everything, nor can it be asked to do just anything. Many sections of Watkin’s book contain lovely commentary on this or that passage of Scripture. But that is just what they are: his own commentary. Watkin’s vast learning, not the plain sense of the sacred page (much less its spiritual sense), is the source of most of the book’s insights. That learning has much to instruct us. But it is load-bearing to a degree that Watkin is not prepared to acknowledge. A truly Bible-only critical theory buckles under the weight of the attempt—not because the Bible is not sufficient, but because of what it is sufficient for: the saving truths of the gospel of God. A Christian critical theory needs more than the Bible. Among other things, it needs sacred tradition.

A truly Bible-only critical theory buckles under the weight of the attempt—not because the Bible is not sufficient, but because of what it is sufficient for.

The second problem is about the sources Watkin relies on, which clarify the nature of his project. He draws on five types of literature: modern philosophy, postmodern theory, academic scholarship, Reformed dogmatics, and contemporary apologetics. That’s an impressive list. What is missing, though, is Christian writing between the apostles and the Enlightenment. St. Gregory of Nyssa gets a cursory mention or two, as do Nicholas of Cusa and Calvin. The only true exceptions prove the rule: Augustine and Pascal, each of whom can be read as a kind of undercover Calvinist, if before and after the letter. (As Calvin wrote, Augustine was “the best and most faithful witness of all antiquity.”)

In short, catholic Christianity—the only Christianity in existence before the sixteenth century and the global supermajority until the nineteenth—has basically no part to play in Watkin’s version of a Christian critical theory. This helped me realize that his proposal is no “merely” Christian critical theory at all. It is not a master discourse drawn from all times and places of the church applied to our time and place. It is an exercise in biblicist Reformed apologetics, written for evangelicals in a postmodern age. Neither I nor countless other believers and time periods are in view. We’re eavesdroppers on an in-house conversation. Watkin so rarely names his presuppositions (a young earth? no evolution? a historical flood?) because he does not need to. He assumes you’re already part of the family, fluent in the speech of the house.

Such an approach can make for a fine project. But it is not what Augustine set out to do in his tale of two cities. Nor would Calvin himself approve, for reasons I will return to below.

Before I turn to Calvin, however, I want to linger on Augustine. For Watkin’s difference from Augustine is the third and most decisive reason for his idealism. When Augustine “out-narrated” the city of Rome, he did so with the city of God. What is the city of God? Answer: The people of God. That is to say, the covenant family of Abraham, a family opened to the gentiles in Christ, by his Spirit. In a word: the city of God is the church. (Plus angels, but we’ll leave that to the side for now.)

To be sure, Augustine has in mind what Christian tradition calls the church triumphant, God’s holy people viewed from the vantage of heaven. Retrospectively, with a kind of God’s-eye view, one can look back and trace the pilgrimage of the true church and her true members, from Adam and Abel to the End. The church in the middle of history is thus the church militant: a martial image for a people at war with the principalities and the powers of this passing age.

The story told by Augustine, in brief, is the story of a people; this people is, in a crucial way, the point of the story; and both the story and the people continue into the present, till kingdom come.

By comparison, Watkin’s “narration” is no story at all. It is a contest of ideas between the Bible, on one hand, and Western society, on the other. Though he calls his account a story, it is not clear what it is a story of. Here is a representative paragraph, in a chapter on Babel:

The two cities will remain intermingled and in conversation with each other throughout the rest of the Bible, until the very end when they are separated at the final judgment. There is a sense in which each of us lives in one and only one of these cities now and a sense in which Christians live in both, depending on how the city language is used. If by “city of God” we mean something like the biblical language of being “in Christ,” and if we equate being a member of the earthly city with being “in Adam,” then any individual inhabits one and only one of the two cities at any one time, and all Christians, by definition, inhabit the city of God.

Notice the remarkable inability to say the little word “church,” underwritten by an emphasis on the “individual.” A salient clue to this pervasive ecclesiological reticence is the sheer absence of baptism, Eucharist, Pentecost, and the Holy Spirit from the book. I am not exaggerating: In a supposed narration of the biblical story, neither the sacraments nor the outpouring of the Spirit nor the Spirit himself warrant mention. I imagined this to be some inexplicable oversight until page 604, when Watkin asks rhetorically, “Have I not even heard of the Holy Spirit?” Well, that’s not an unreasonable question, given the foregoing. Perhaps readers are due an answer.

At first glance, the missing Spirit might suggest an overly materialist analysis. But the opposite is the case. As Eugene Rogers has observed, the Spirit makes himself known in bodies: in persons, matter, and meals. Subtract the Spirit and you subtract as well the church and her sacraments; the two go hand in hand. Hence Watkin’s idealism: his theory isn’t nearly materialist enough. While he promises to interrogate institutions, practices, and technologies, mention of these predictably defaults to ideas, values, and abstractions. The ideals supervening the biblical narrative combat the ideals of Western culture. Diagonalization glides along the surface of both, ensuring rolling victories of the former over the latter.

A reader would be justified in being skeptical. It just seems too easy. Watkin is preaching to the evangelical choir. I am a sometime member of that choir, yet I still found myself regularly befuddled, unconvinced, or disappointed. There is a better way.

Ecclesiology, sacramentology, and tradition are non-negotiable elements in any account of the Christian faith, let alone an attempt to build a critical theory for believers on a par with Augustine’s City of God. The Lord’s mighty works narrated in Scripture are not merely past tense. They are present here and now. Theologians and other Christian writers must be vigilant, therefore, in refusing either to reify or to fossilize them. What, according to St. Paul, is “the mystery hidden for ages in God”? Namely, “that through the church the manifold wisdom of God might now be made known to the principalities and powers in the heavenly places” (Ephesians 3:9–10). The church is intrinsic, not extrinsic, to the will and work of God in the world.

Consider how John Milbank concludes his own book on this topic, Theology and Social Theory, published more than thirty years ago. Regarding the Christian metanarrative, he argues that “the metanarrative is not just the story of Jesus, it is the continuing story of the Church, already realized in a finally exemplary way by Christ, yet still to be realized universally, in harmony with Christ, and yet differently, by all generations of Christians.” He goes on, “The logic of Christianity involves the claim that the ‘interruption’ of history by Christ and his bride, the Church, is the most fundamental of events, interpreting all other events. And it is most especially a social event, able to interpret other social formations, because it compares them with its own new social practice.”

In other words, the protagonist of history is Christ, but not Christ alone. In Augustine’s formulation, it is the totus Christus: the whole Christ, head and body. As Paul writes, “the creation waits with eager longing for the revealing of . . . the children of God” (Romans 8:19, 21). St. John spies a glimpse of this finale when he sees “the holy city, the new Jerusalem, coming down out of heaven from God” (Revelation 21:2). It is this city, the bride and body of Christ, that will endure. It is her story that the Spirit is writing in real time. Writing our own stories in his shadow, we do well not to forget that.

John Calvin, for his part, never forgot it. It may be the case that church, sacrament, and tradition—even the Spirit!—are oversights in modern evangelicalism. Not so in Calvin. The late John Webster called Calvin “arguably the first and last great Protestant theologian of the Spirit.” This greatness is evident in his magnum opus, Institutes of the Christian Religion, one-fourth of which is dedicated to the church: her calling, her mission, her worship, her pastors, her sacraments, her place in civil society. As Calvin writes, “let us learn, from her single title of Mother, how useful, no, how necessary the knowledge of her is, since there is no other means of entering into life unless she conceive us in the womb and give us birth.” So exalted is his doctrine of the church that Calvin can affirm St. Cyprian’s dictum, extra ecclesiam nulla salus: “beyond the pale of the church no forgiveness of sins, no salvation, can be hoped for.” For this reason “the abandonment of the church is always fatal.”

In sum, “What God has thus joined, let not man put asunder: to those to whom he is a Father, the church must also be a mother.”

There is much more where that came from. Calvin, like the other reformers and their predecessors, is a rich vein ready to be tapped. It is he whose critical theory unveils the sinful human heart for what it is: a factory of idols. We desperately need analysis like his today. Following Calvin, a Christian theory need not be Roman to be catholic; need not be recent to be relevant. It must avoid, however, leaving out what is essential. Idolatries old and new abound in our time, and we need all the help we can get. We need the whole counsel of God, preserved and propounded by God’s people and handed on, through them, by God’s Spirit.

Let us therefore be grateful to Watkin: his book is apt to our moment; it should inspire other attempts, not foreclose them. Watkin calls his book but “a warm-up act,” meant to “prime the pump.” We should take him at his word. Together with him we still await “the main event.”