Lawrence Lanahan is a good storyteller. Read his stories about jobs for people without college degrees or listen to his yearlong public radio series about inequality and segregation in the Baltimore region, The Lines Between Us. Or read his debut book, also called The Lines Between Us, about two families living in the same metro region but in different worlds and their journeys across segregated lines. I could hardly put the book down as I read it, even though I knew a fair amount of it already. I am pretty much Lanahan’s target audience, which is my main criticism of the book: I am not sure how much people who don’t already understand what Lanahan is saying and have already wrestled with the questions he raises will get out of reading it. At the same time, it’s a book that doesn’t really provide a strong argument for the changes he wants to see in contemporary housing policy and chooses to simply tell stories rather than discuss the best ways to deal with the legacy of segregation.

The biggest question regards two strategies for alleviating the poverty that is a direct result of historic segregation, generally referred to as “place-based community development” and Moving to Opportunity. (The latter is the name of a formal federal program and shorthand for a strategy, which is why it is usually capitalized.)

Place-based community development looks at a neighbourhood in West Baltimore like Sandtown, with its murder rates usually among the top five in the city, its life expectancy a full twenty years lower than high-income neighbourhoods a mile away, its incarceration rate higher than anywhere else in the state, and asks: How can we help transform this community for the better?

Moving to Opportunity looks at the same neighbourhood and asks: How can we help people—especially families with young children, who might be able to do much better elsewhere—get out of such a bad neighbourhood?

In some ways, it doesn’t seem like the strategies would be terribly incompatible, but limited government funding and some inherent philosophical tensions draw the two into conflict. On the one hand, cities like Baltimore (and the metro areas surrounding them) were deliberately shaped by policies designed to exclude and impoverish black Americans. Providing opportunities to live in better neighbourhoods with better schools in counties that whites fled to decades ago only seems fair. On the other hand, one cannot simply extract people (often some of the strongest members of a community) from a neighbourhood en masse; doing so only leaves the most desperate and vulnerable behind. One has to do something for those communities to help them, and providing subsidized housing seems like an important part of that equation.

The Lines Between Us follows two stories illustrative of these two different strategies and another story about the fight between them. In one, a black single mother named Nicole Smith takes advantage of a Moving to Opportunity–style program to use a Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) voucher and move to Columbia, a majority-white suburb designed to be a community for all. There she is able to finish her community college degree, start a child-care business, and get her son into the Junior ROTC program at a nearby high school. Meanwhile, a white couple named Mark and Betty Lange moved from suburban Harford County into one of Baltimore’s most poverty-stricken neighbourhoods to be a part of New Song Community Church, a church dedicated to place-based community development. Interwoven with these stories is Lanahan’s narrative of the decades-long legal saga in Thompson v. HUD between advocates for the poor and the struggling government agencies responsible for carrying out the dictates of the Fair Housing Act. The argument that the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund (with the ACLU as co-counsel) sued over in the case was whether public investments primarily in Baltimore’s most segregated areas failed to “affirmatively further” the goals of the Fair Housing Act, namely, reversing the work of segregation, and poverty along with it. Baltimore city solicitor Thomas Zollicoffer argued in opposition that the plaintiffs were trying to goad HUD to “take money from Baltimore City and disinvest in Baltimore City and send it out to the counties.” There’s no easy answer.

Disclosure: Christian Community Development Changed My Life

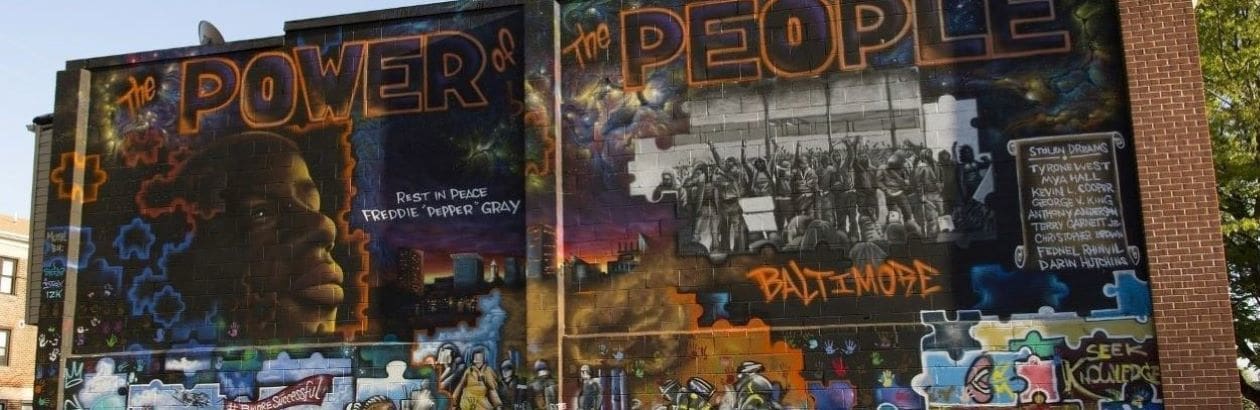

I have to mention that I knew what I knew about the book before I read it because I was a source for the book and was present for a number of scenes recounted within it. My wife and I are members of New Song Community Church, Mark and Betty Lange are our friends, and because we also intentionally moved into the neighbourhood Lanahan included me in some of his previous reporting about the church. He and I have become friends over the past few years, and I cannot help but cite his work whenever I try to talk about Baltimore and what I learned from the years that I lived there. Our kids were baptized at New Song, the elders anointed me with oil and prayed over me when I faced a life-threatening illness, and the church prayed over our family as they sent us out to be the first foreign missionaries from the church. I teach and practice medicine at a hospital in Kenya now, but I lived in Sandtown when Freddie Gray died and on April 27, 2015, the day that decades of simmering anger at police brutality and segregation boiled over into a riot blocks from my house. I spent most of the afternoon frantically trying to get in touch with my housemate who ended up accidentally driving through the riot to get back to our house. (She made it to us by dinnertime without a scratch on the car, thank God.) If this essay reads like me opening a vein on the page, it’s because I don’t know any other way of writing it.

Here is the thing about New Song Community Church: I walked through its doors in 2008 when it was everything kids these days say they want in a church. There was strong preaching from a black pastor full of deep concern for holistic justice that didn’t compromise an iota of theological integrity; there was majority-black leadership; programs connected to the church met needs within the community, with people of all races and backgrounds working together to help provide health care, housing, and jobs for a neighbourhood devastated by the legacy of segregation in Baltimore. Even the worship band was solid, playing a mixture of contemporary worship songs, classic hymns, and Gospel standards. Coming from a conservative church in a majority-white suburb where a sermon on social justice would have been about as out of place as the Tupac shirt that one of the ushers carrying the collection plate at New Song was wearing, it was a breath of fresh air and an opportunity for me to learn and listen at an age when I was a little too high on my opinions. I fell in love and moved in.

The church was founded in the ’80s by two friends named Allan Tibbels and Mark Gornik. Allan was a quadriplegic, but that did not stop him from moving into Sandtown at the height of the crack epidemic with his wife and two young daughters. Allan had been reading the work of John M. Perkins, a black man from Mississippi who watched his brother bleed to death after being shot by police and was himself beaten severely by police in jail. Perkins later came to Christ and founded a passionate movement called Christian Community Development, which saw churches as the primary nexus for change in America’s neglected places (particularly in rural and urban areas).

Mark Lange and Allan were friends back when Allan was a youth pastor in the suburbs getting more radicalized into the ideas of Christian Community Development, but Mark remained in the suburbs for more than a decade enjoying his American dream. All the while, he felt his conscience pricked by his interactions with coworkers in the city and his previous experiences with Allan working with teenagers in and around the city; eventually he moved into Sandtown and Betty followed later. For both, it was John Perkins’s ideas that led both of them to the conviction that they had to be a part of the community of Sandtown in order to best serve the people there.

Perkins’s philosophy was simple but demanding, centered on “the three Rs”: redistribution, relocation, and reconciliation. Redistribution of resources, tangible and intangible, is necessary in helping poor communities to thrive. However, Perkins argued that this redistribution should take place primarily in the context of relationships formed through relocation—that is, people with privilege and power should relocate to areas with less of both in order that they might walk beside people in those communities and be a part of that redistribution. Relocation, then, also creates opportunities for reconciliation across economic and racial barriers as the church works out practically what Jesus accomplished on the cross as “our peace, who has made us both one and has broken down in his flesh the dividing wall of hostility” (Ephesians 2:14). Not only is all of this meant to take place in a context where listening to the members of the affected community and letting them set any agenda for development is prioritized, but those community members are also meant to be developed into leaders.

It’s a model that has found success in several different places, perhaps most prominently in the first place where Perkins tried it, in Mendenhall, Mississippi, and in the Lawndale neighbourhood of Chicago. As Lanahan describes in the book, New Song in Baltimore peaked in the mid-2000s, and then came a series of heavy blows: Founder Allan Tibbels died in 2010; outside funding dried up during the Great Recession, precipitating the closure of a church-affiliated neighbourhood business and the closing of the urban ministries’ umbrella organization; and the lead pastor left in 2013 to answer a call elsewhere. The book mentions many other struggles the church experienced that have led to lower attendance and fewer programs, but perhaps the biggest one that was not mentioned is the fact that there was a strong first generation of leaders from the neighbourhood, but the second generation was snatched away. The church invested heavily in a large group of kids, particularly through a youth choir that recorded albums and toured around the country. Once I was walking up the stairs with a fellow church member from the neighbourhood; as we gazed at a wall-sized print of the youth choir’s album cover she pointed out those who had been shot, arrested, gotten pregnant as teens, or dropped out of school faster than I could process. These were the people who, along with us “relocators” from outside, could have helped carry the church through the difficult times of 2008–2015, but there just weren’t enough of them.

Show, Don’t Tell—But Then, Preach!

The main weakness in The Lines Between Us is that there is almost no editorializing or summarizing. What worked extremely well for Lanahan in a public radio series does not hold as well over nearly three hundred pages of different narratives covering decades of regional housing policy and different human lives; all the pieces are there, but there’s no clear discussion of what it all means or a summary of the journey that the different characters made. (This radio interview does provide a good summary, if you’re interested.) What reflections are present in the text are interspersed within the narrative, and it is easy to miss them as such unless you’re looking for them. This is because Lanahan loves to choose a strong quote from one of his sources or public records to sum up the tension, as with the quote from the city solicitor above.

The book is not an argument about how segregation worked and still affects us today (The Color of Law is that book about housing specifically), but some of that introductory material would have been helpful in setting up what comes. An introductory (or conclusory) section taking in the big picture would also have been a good place to talk about other issues that shape the debate about the housing crisis in America: single room occupancy, demolition of vacant housing, or regulations regarding historic preservation are all incredibly relevant in Baltimore. A good chunk of the last chapter is spent on Tax Increment Financing projects like Port Covington in Baltimore, but the only connection between this material and the rest of the book is the way in which activists decrying disinvestment are pitted against city administration bumbling along from project to project. Lanahan is trying to fit this battle into the legacy of Thompson v. HUD, but it doesn’t feel like it has the same stakes as that case and it doesn’t expand into a discussion of what a robust regional strategy for desegregation and poverty alleviation would look like.

Without overarching themes or editorial comments drawn from this background work, we’re left chasing two spectres lurking throughout the book: funding shortfalls and other homeowners. The former simply defines the size of the “pie” that can be divided between different funding strategies (and the pie, unfortunately, is small). The latter comes out to protest every time there’s a rumour that HUD may be helping black people from the city move into more prosperous communities, complaining that the possibility of increased traffic or overcrowded schools outweighs any benefits that people from poorer, more segregated areas might experience. At best, it’s gobsmacking indifference to inequality; at worst, racism and classism.

The challenge in terms of audience for the book, I would guess, is that a majority of white Americans are sympathetic to the concerns of those who would prefer to see poorer people kept out of their neighbourhoods by zoning or moaning. Lanahan lets them speak for themselves in the book (“What kind of a quality person are you going to get who’s paying $380?” asks one local politician when debating legislation that would allow HUD to build low-income housing in his county), but the force of their argument is still far too strong in too many places. Perhaps the book is meant for liberals who are “doing with zoning and Nimbyism,” as Farhad Manjoo points out, “what Republicans want to do with I.C.E. and border walls.” But even then when Lanahan winds up for the punch he never throws it hard enough. With the national mood still essentially indifferent to whether America continues to keep its most historically oppressed communities segregated (or actively hostile whenever desegregation is proposed in their own backyard), we could use some more fighting words trying to puncture that attitude.

What if churches took the time to learn about how segregation shaped the region that they live in and prayed about what their response to that history ought to be? What if our emphasis on “reaching the city” was primarily one of partnership with African American churches that have been serving the city for decades, rather than “urban church plantations”?

Even if it is not meant to convince the average National Review or The Nation reader that they should just chill out the next time HUD wants to build an apartment complex in their “six figures” suburb (a real objection raised by someone in the town adjacent to the one I grew up in), The Lines Between Us should have at least discussed the central tension between place-based community development and Moving to Opportunity. In some ways, the stories told seem to favour Moving to Opportunity, at least for individuals: The court ruled that HUD did not affirmatively further fair housing enough, requiring that the government expand the program that served Nicole Smith, who moved to Columbia from West Baltimore, so well. Meanwhile, Lanahan tells us that Allan Tibbels and Mark Lange ruminated just before Allan’s death that maybe the church hadn’t been particularly successful in doing much except helping a few people own their houses instead of renting. With the church operating far fewer programs and hosting far fewer worshippers now than it did when I first walked through its doors over a decade ago, it’s hard not to feel like perhaps Christian Community Development isn’t all it was cracked up to be when I was still a young, idealistic medical student.

It’s not a binary choice between two options, and the book doesn’t make it out to be one. If the goal is desegregation and reducing poverty, then of course wealthier communities in the suburbs should allow more low-income families to live there—and of course something has to be done to help those who remain behind in poor, segregated communities. It should not be hard for families whose children are suffering in crumbling public schools and walking past drug dealers to move to a place where their kids can be safer, but any “regional strategy” (as it is repeatedly referred to in the book) to deal with concentrated poverty is not going to contribute significantly to the recovery of any blighted neighbourhood if the people in that neighbourhood have to live, work, or go to school somewhere else in order to thrive. (Not to mention the difficulties with the unnatural nature of the suburbs themselves!) The ultimate utility of Moving to Opportunity has to be weighed in this balance.

Reversing Redlining in the New Jerusalem

What makes the balance even harder to strike is the fact that helping families move out of places like Sandtown is to pick a fight with Bull Connor’s grandchildren on both sides of the political aisle and invite the scorn of best-selling Christian authors. Where conservative, evangelical churches ought to have been leading the nation in repentance, instead significant churches and figures were leading the charge to re-segregate schools and looking the other way when it came time to settle up for what was done. Segregation was one wound among many in the long scourging that is American history vis-à-vis the black body; rather than asking how to foster healing, many white Christians have tied the edges of the skin apart and keep remarking loudly on how things keep getting infected.

Many Christians are not sanguine about the government’s role in ending segregation. Fair enough; Thompson v. HUD demonstrated that the state’s attempts to desegregate over the past fifty years leave a lot to be desired. Not even the secular liberals are terribly excited about integrating by class or income. What if the witness of the church of Jesus Christ was different? What if, like Josiah hearing the Book of the Law and tearing his clothes, the church heard our history and rent our garments in repentance? What if churches took the time to learn about how segregation shaped the region that they live in and prayed about what their response to that history ought to be? What if our emphasis on “reaching the city” was primarily one of partnership with African American churches that have been serving the city for decades, rather than “urban church plantations”? What if God-fearing believers corporately mobilized to treat the moral problem of ongoing segregation with the same seriousness that we treat the evils of pornography or abortion in America?

The story of New Song Community Church is not the stirring example I wish I could point to for other churches to model. Perhaps, like the story of Jim Elliot, the sacrifices that those of us in the church made will have some more glorious and obvious payoff. Perhaps not. What I can say that is that I gained far more perspective on what my American brothers and sisters have suffered and still suffer from segregation than I ever could have got from a book and that I hope my friends in Sandtown were blessed in some small way because I came to listen, learn, and serve. New Song may not be the model, but John Perkins’s three Rs could still use another few hundred iterations before we declare the theory unproved. If we want to see concentrated poverty and the legacy of segregation erased, I don’t see another way.