The past can be a dangerous place to visit. Sometimes it’s best to leave it alone. At least for a time.

***

Geoff had just given himself a shot. The familiar euphoria was only beginning to warm his body when his homie, Anthony, pled with him to help someone else shoot up for the first time. Through the descending haze Geoff recognized that Anthony was directing him toward Angel, a woman he had been with in the past. Geoff wanted to ignore the request: heroin-induced surrender was seducing his senses, and he just wanted to submit. But two realizations slowed him from letting go. First, Geoff loved being the “hookup.” He loved that Anthony thought he was the right one to initiate Angel into the exclusive clan of hypodermic connoisseurs. And second, he hated Angel. She was having sex these days with Anthony, after claiming no one satisfied her like Geoff. Never mind that Geoff slept with anyone marginally available. She was stepping out on him—an unforgiveable betrayal.

Geoff loaded up a rookie-sized shot, habitual skill fighting the sweeping haze. Then he loaded it with an extra dose. Minutes later, Angel died.

***

One of Lizzie’s first memories dates back to when she was living under a bridge with her mom. Too often passed out on drugs or busy performing sex services, her mother left Lizzie to feed, clothe, and protect her younger sister. At five years old, Lizzie was introduced to meth by her mother. The pervasive feeling of overwhelm at premature caretaking gave way to feeling like superwoman. Lizzie gradually became everything she hated about her mother, including that her body was her worth. The only thing Lizzie couldn’t stomach was her mother’s penchant to let men do to her whatever they wanted. Lizzie was different. Over the next twenty years, Lizzie would be arrested and incarcerated dozens of times for an escalating pattern of crimes, including the attempted murder of a boyfriend.

***

Raul grew up in a business, not a family. His home was a hub of gang and drug activity. He can’t remember the day he gave up on craving tenderness and safety from his mother and father. But he easily recounts the day he and his brother viciously beat a local pastor because he had called the police on Raul’s “family.” Raul was eleven at the time. It was Raul’s “bar mitzvah.” A rite of passage. He had proved he was “down for the gang.” Raul spent the next thirty years in ardent pursuit of “reputation.” He dreamed of one day commanding his own gang regiment or, as a backup plan, becoming the shot caller in a prison.

When History Is Identity

Conscience is a competence that involves responding to subtle feelings. It means learning to discern whispered moral directives through a din of screaming impulses.

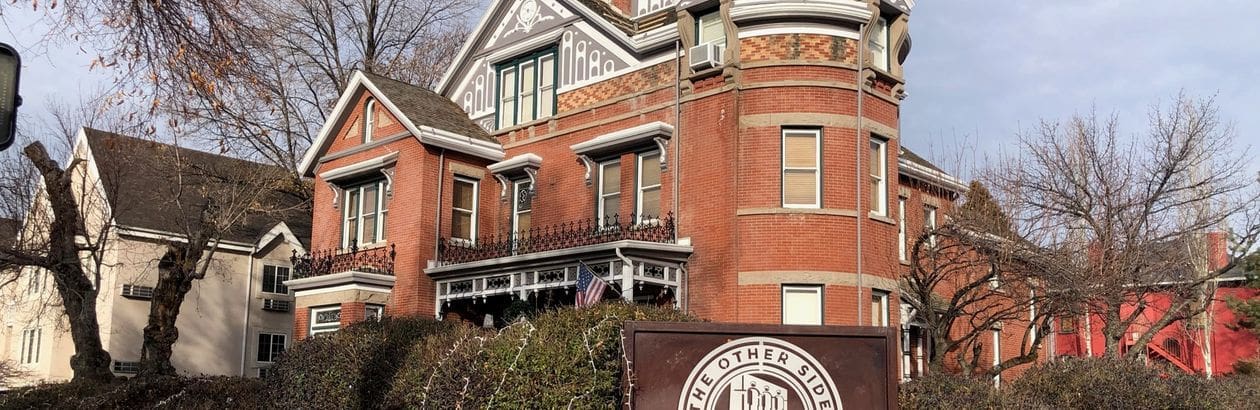

Every week a handful of adults ages eighteen to sixty like Geoff, Lizzie, and Raul enter The Other Side Academy’s main entrance in a stately nineteenth-century Victorian mansion to sit on The Bench. These men and women have been arrested an average of twenty-five times. Some have spent decades incarcerated. Others have lived for years on the streets. Most are facing lengthy new jail or prison sentences. Some are violent criminals. All are long-time addicts.

If accepted as a new student, they commit to stay a minimum of two and a half years. They pay nothing to attend, and no outside agent pays anything for them to attend. Instead, those accepted spend years learning to be self-reliant in one of the most demanding moral communities in the world.

Our goal is to help deeply broken people become a person they have never before met. And the first rule they must follow in order to reinvent their lives is: Don’t talk about your past.

Some find this curious. Santayana’s assertion seems axiomatic to most of us: “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” Santayana would be right if all we looked to the past for was information. But when Geoff, Lizzie, and Raul first arrive at The Other Side Academy, their past is not just a bucket of information; it is evidence of identity. Their assumed dogma is as follows:

What you’ve done is who you are.

Who you are is who you’ll be.

Therefore, what you’ve done is who you’ll be.

To Geoff, his history is incontrovertible proof that he is a selfish junkie and sex-crazed murderer. Raul’s life convinces him that he is a feared and respected gang leader. And all Lizzie knows is that she is an ugly and formidable prostitute. Not only do they arrive at The Bench with conviction that their present is their past; they have a still more crippling belief that their past is their potential.

The most liberating message The Other Side Academy presents is that it is your present, not your past, that defines your potential. If the past were the best indication of potential, there would be no such thing as human progress. If these new students were allowed to regale their new community with their past exploits, the very recounting would further extend their servitude to the very identity they must shed. Students who visit the past too soon are the ones who invariably repeat it.

Deep change becomes possible for The Other Side Academy students when they begin to entertain a more hopeful logic:

While what you’ve done is who you think you are,

What you do now shows who you can become.

Convincing our students of these, though, is a long and arduous battle. While at times a still small voice may suggest the truth of their divine identity, it fails to rise above the prosecutorial din of their lived history. It’s hard to embrace the possibility of a transformed orientation when all you feel are the consequences of past facts. How can you feel hopeful when you’re arraigned by the remembered faces of hundreds with whom you’ve defiled yourself, just so you can stick another needle in your arm? How can you credibly claim moral distance from the self who stabbed his own cousin? Or abetted the death of a past lover in a fit of jealous pique?

Students must prepare before they interrogate the false beliefs they’ve held. They must first assemble sufficient evidence that conflicts with their old identity if they’re going to mount a violent campaign against it. And make no mistake, the old one won’t die without a fight.

Act as If

The best way to become a new person is simply to act like one. We don’t care if you feel like a compassionate person; we just tell you to act like one. We don’t care if you think you’re a compulsive liar; we care if you act like one. Your brothers and sisters at The Other Side Academy don’t care if you have pride in your work; we care that you act like you have pride in your work.

History is a dangerous place to visit if you’re not strong enough to come as an author rather than a passenger.

The Other Side Academy is a house of truth. Immediate truth. Unvarnished truth. The strongest norm in the house is called 200 Percent Accountability. You are taught quickly that the fastest way to get into trouble is not to do something wrong (the first 100 percent); it is to fail to correct someone else when you see them doing something wrong (the second 100 percent). Your moral duty is to save the lives of your brothers and sisters. And the way you do it is by giving them corrective feedback at every opportunity.

Few students get into the spirit of it right off the bat. But they fail to obey the letter of it at their own peril. The harshest feedback you’ll get is for failing to correct others—your brothers and sisters will point out how selfish you are. They will accuse you of not giving a damn about the lives of the people around you. Soon you start offering correction simply to get others off your back. And we don’t care if you start there. Act as if. Act as if you care about others, and eventually you will.

Lizzie reluctantly follows the norm in her early days. She forces herself to remind other women to push in their chairs after leaving the dinner table. When she sees an older sister smile at one of the men, she confronts her. When one of her leaders is grouchy, she reminds her to “have a good attitude.” At first she only does it because she knows she’ll get called out if she doesn’t.

But then one day she is in the basement walking to the pantry with an armful of toothpaste. She passes an open door. It strikes her as odd—people don’t leave doors ajar at The Other Side Academy. She sees a sliver of shadow on the ground confirming her suspicions that someone is standing quietly in this utility room. The old Lizzie would have felt nothing. But this Lizzie comes to an abrupt stop. She feels concerned . . .

Human virtues are hard-wired into all of us. They are part of our moral DNA. Some people’s lives, either through trauma, choices, or a combination of the two, damage the capacity for empathy and guilt. But they cannot excise the starting ingredients of moral reasoning, however twisted that reasoning becomes.

In their learned zeal to avoid painful feelings, our students tend to find ways to stop all feeling, including the felt difference between right and wrong. And when you can’t feel the difference, you stop caring about it. Me and now are the prime directives of life. You can rack up a pretty mottled history when these become your ethic.

Conscience is a competence that involves responding to subtle feelings. It means learning to discern whispered moral directives through a din of screaming impulses. For The Other Side Academy freshmen this is tough. It’s like trying to hear a cricket at a Megadeath concert. So we teach them how to simply act as though they have a conscience.

Acting as if is like CPR for the conscience. CPR works because if you make the heart act like it’s pumping blood, you bring oxygen to it until the electricity it requires returns. We trust that if you do virtuous things long enough, you’ll eventually feel the electricity of virtue. Undeveloped capacities for empathy and guilt can be animated by going through the motions that exercise them. Motive doesn’t matter at the start. But it inevitably evolves if you act as if long enough. You begin to feel what virtuous people feel when they conform to their conscience, if you stick with it.

The highest calling of conscience is vicarious sacrifice. It’s taking yourself to a place of discomfort for the benefit of another. At The Other Side Academy, we urge our students to risk the condemnation of a peer by confronting their lapses.

Lizzie’s feet stop. She isn’t sure why. Her body begins to do things that surprise her, no, impress her. She pushes open the door. One of her brothers looks up awkwardly. He’s figured out how to connect an automobile diagnostic tool he’s been using on The Other Side Academy vehicles to the internet, and is about to send an email to his girlfriend. If he succeeds, he will be walking himself to prison, possibly death. Instantly Lizzie confronts him. He makes a diffident attempt to dissuade her from telling on him. But her feet are already in motion toward a house leader. The infraction is addressed, and his life is saved. Through it all, Lizzie feels a thrill of purity she has never known.

Six months into his stay at The Other Side Academy, someone inadvertently opens the house safe near Raul. The old Raul effortlessly assembles a complex plan to benefit from his good fortune. He writes the combination on a scrap of paper and buries it in his pocket. He immediately knows when he’ll open the safe, which other assets he will purloin, and how he’ll boost a vehicle to make his escape. All this happens with sickening automaticity in a matter of seconds.

But over the next two weeks something new happens. An unfamiliar chafing gnaws from within. He puzzles over its source for days. Then at breakfast one morning one of his brothers brings him a breakfast plate. There’s nothing unusual about this. But as the plate settles on the table Raul says thank you. And he means it. He feels grateful. He feels undeserving of the simple kindness he just experienced. He reaches to his left cheek and realizes it is wet. He is crying. After breakfast he approaches one of the house leaders and hands him the paper with the combination. In a torrent of honesty, he not only admits to his plan, but he sheds countless other deceits accumulated over months. As though standing outside himself, he marvels at what he is doing. And that he wants to do it. As he walks away, knowing he will be punished for the many offenses he confessed, he is happy. Deliriously happy.

Before a student can successfully reappraise their previously undisputed story, they must first weaken it. The first precondition of any paradigm shift involves exposing the paradigm. We must first see that the map is not the territory; it is simply a story that seemed to fit the facts. And second, there must be dissonance—an annoying accumulation of experiential outliers that don’t fit the old story.

I do things I have never done.

I feel things I have never felt.

Therefore, I question who I really am.

At The Other Side Academy, students act as if until they begin to marvel at their own behaviour. This can be deeply uncomfortable. The discomfort provokes some to leave. They choose a familiar hell over an unfamiliar heaven. Life between maps is disorienting, even terrifying.

But most see it through. They are intrigued with the possibility that their entire past can be explained with a new story, one that doesn’t demand defining themselves as evil or worthless. The dissonance reaches a threshold level when students not only act as if but also feel as if. It is at this point that the possibility of a new story is not only intellectually viable but also viscerally plausible. Now it’s time to re-examine history.

Confronting Our Stories in Community

It’s nine in the morning on a Saturday at The Other Side Academy. Six men, including Geoff and Raul, sit in a circle on couches and overstuffed chairs. They chat nervously. For six to eight months they have lived and worked together, but never spoken about their past. For the next twelve hours they will now expose their past to intense scrutiny.

They’ll be assisted aggressively in this effort by four mentors whose authority comes from having escaped the same narrative prisons. These mentors will help these men not simply by recounting what they did, but by explaining it in a new way. They will identify the pernicious fiction that enthralled them. They will recognize the myriad ways they chose to serve it. And they will rewrite the sinister subtexts of their life in a way that offers their first real freedom.

But no tyrant dies without a fight. Challenging people’s stories is a full-contact struggle. The old person with the old story sees this Sophomore Retreat as an existential threat, and rarely surrenders quietly. Clashes take place as the student defends distortions they have upheld for decades. The most common ones include the following:

1. Unearned shame. Most students were physically, sexually, or emotionally abused before they were old enough to understand what was happening. Lizzie shares how as a child she offered herself to a man her mother had brought to their camp for sex. She saw him approaching her younger sister and felt it her duty to defend her from his molestation by offering her own body to him. After all, by this time she had already been molested repeatedly by an uncle. These kinds of experiences left her feeling dirty, damaged, and unlovable. As Lizzie recounts these episodes, others press her to identify, interrogate, and rewrite the conclusions she’s drawn from them. In multiple rehab experiences she received professional counselling for these nightmare traumas. And some of it helped. But none seemed as credible to her as the guidance she got from women who had conquered the same demons. As her story continues, she sees how many of her future choices were logical extensions of this crippling view of herself. A fiction she served as a reality. The shame dissipates as she reassigns the roles of victim and perpetrator in her story.

2. Uneven accountability. A surprising number of students begin to recount their histories with a phrase like, “My parents were amazing. I had a great childhood.” Most of the time this sentence is defensive, not truthful. Geoff describes his father as a great provider and family man. His mother was a saint. Geoff lawyers up for his parents as others point out the tragicomic inconsistency between his headline and the story. His father was a philanderer and his mother a doormat. He refuses to concede to what’s obvious to everyone else. The truth has no agenda. And until Geoff surrenders his own agenda, he can’t build his future life on truth.

He protests vigorously for an hour as his mentors challenge him to expose everyone to equal scrutiny. When he comes to his story with unexamined motives, his story swings between blame and excuse. He blames Dad and absolves Mom. Eventually he sees that at some level a blame story is a tool for excusing yourself, and an excuse story satisfies an unexamined need. After two exhausting hours, Geoff starts to see the wisdom of learning to love virtue and measure everyone against the same standard.

3. Facts without feelings. Raul tells his story like a CSPAN narration. The content and the tone are horribly mismatched. He describes brutal attacks and heartbreaking betrayal like he’s reading the phone book. “When I was in prison I had to stab my cousin,” he intones. You can’t heal what you don’t feel. When you’ve seen yourself a certain way for a long time, you begin to turn identity into permission. So, members of the retreat arrest his narration. They raise their voices on behalf of his victims. They demand that he tell the story from their perspective. They coerce him to confront the moral truth of who he has been and what he has done. As he does, he chokes. His shoulders begin to heave. He collapses in cleansing guilt. And as he feels new feelings about past choices, he gains a distance from them that presents the possibility of a different future.

4. Mistaking love and need. It’s hard to surrender the illusion of love when you’ve had little or none of the real thing. But it’s crucial to do so if you want to claim a future with real love, one where relationships include boundaries. In the retreat, some of the most intense struggle is fighting to redefine the word “love.” Lizzie describes an incident when her boyfriend, while strung out on meth, attacked a man with an axe who had attempted to strike her. “He was the only man who really loved me.” But the only moments she describes as intimate involved sharing a needle before having sex. This was apparently as good as it got.

Through vigorous confrontation she opens her eyes to the rest of the story. He cheated on her. He used her to get people to open doors so he could burglarize them. He got her to use heroin when she had struggled to stay clean for three months. As the group chips away at her defenses, she comes to see that what she felt in this relationship was not love but need. Lacking any internal conviction of her worth, she’d seized on the tiniest shred of external evidence. His miserable companion offered the illusion. Until students mine their souls to define their value, they cling addictively to others in a way that palliates their gnawing need while validating their insecurity. In the end, the frantic need for others is evidence of inadequacy.

Geoff emerged from his Sophomore Retreat with important new insight. He faced and felt his own depravity. He unapologetically acknowledged the influence his parents’ defects had on him. He jettisoned his delusional view of the woman he had previously intended to return to after graduation.

When Lizzie ventured into her past, she did so after coming to see a new possibility in herself. She had shown herself to be a woman with boundaries, integrity, and courage. She had intervened numerous times at significant personal risk to save the life of a brother or sister. As she reviewed past events, she stood on ground high enough to give perspective. The way she had behaved then were possibilities, not destinies. Having done things she had never done, and felt things she had never felt, she came to see that her identity isn’t owned by her past but her present and future.

Raul’s first breakthrough was summarized in two sentences: “I thought I was a respected gang member. I see now that I was just a desperate junkie.” It was deeply unsettling to repudiate hard-earned reputation as a source of worth. But by this point Raul had accumulated enough novel experiences and feelings that he had confidence in a better reality. His new identity, in his own words, is this: “I no longer care about reputation. What I want is character. I don’t want to chase others’ respect. I want to respect myself.”

Saving the Community That Is Saving You

History is a dangerous place to visit if you’re not strong enough to come as an author rather than a passenger. Sometimes the preparation involves separation: living apart from the past long enough to be able to reveal and weaken its previously intractable assertions. And sometimes it involves gathering allies who, having triumphed over their own narrative prisons, can help you escape your own.

While The Other Side Academy is not a faith-based community, as a Christian I witness divinity in the abundant miracles of personal change worked in this sacred space. God’s most desirable promise is not forgiveness but transformation. He doesn’t offer to simply forgive us of our histories, but to sever us from them. We are the insurmountable barrier he faces as he attempts to make us new creatures in Christ. In response to his declarations about our true pedigree we rehearse accumulated evidence of our irredeemability.

Knowing this, he invites us into covenant community. Our most sacred work is not sitting shoulder to shoulder in peaceful worship, but sitting face to face in intimate conflict. We first entertain the possibility of our own redemption when we see the completed miracle in those once similarly broken. We persist against our inner accuser when those who see us in terrifying new ways demand it of us. And eventually, through the vicarious sacrifice of these mortal saviors, we surrender to the still small voice that speaks of who we were always meant to be.