S

Social movements that have toppled dictators are often remembered for their raucous protests and arresting images. But in The Quiet Before: On the Unexpected Origins of Radical Ideas, Gal Beckerman argues that underground incubation periods among believers precede any public spectacle. This quiet is important, yet Beckerman worries that the internet—particularly social media—gets in the way of this necessary stage of incubation, weakening the ability of movements to advance good changes in society.

While the internet does not intrinsically inhibit these quiet conversations, most of us interact through large platforms like Facebook and Twitter, which monetize maximal membership and engagement. And what engages is what enrages. Likes, hashtags, the race for followers, and the shield of anonymity promote the gladiatorial spectacle rather than the careful, quiet deliberation needed at the beginning of movements. To help make this argument come to life, Beckerman carefully mines accounts of various incubation periods and provides important lessons on shepherding movements in and through the digital age.

The Three Acts of Social Movements

Social movements might be thought of as comprising three acts. The first act is the subject of Beckerman’s book: small, enclosed, private conversations. The second act is the public salvos of protests, marches, and boycotts that first etch history books and now glow on our screens. The third act deploys power for lasting gains and the acceptance of a new normal.

Before getting to Beckerman’s first-act principles, an inventory of the historical case studies he presents reveals the diverse forms that the quiet can take for various social movements. Beckerman recounts ten movements spanning five centuries and three continents, from 1635 in Aix-en-Provence to 2020 in Minneapolis for Black Lives Matter. Note that the first six are pre-digital movements propelled by letters, manifestos, petitions, samizdat (illicit newspapers), newspapers, and zines, while the latter four are digital movements propelled by social media platforms.

- 1635, Aix-en-Provence: Nicolas-Claude Fabri de Peiresc, a natural philosopher and astronomer, recruits and coordinates collaborators through years of letters so that for one night they all record the time of the lunar eclipse in their respective locations to correctly measure the length of the Mediterranean Sea.

- 1839, Manchester: Feargus O’Connor assembles over a million signatures among the disenfranchised working class to petition for expanded voting rights.

- 1913, Florence: Futurists Filippo Marinetti and others employ the manifesto as a canvas to imagine a society propelled by technology’s speed and shaken from slumber by war.

- 1935, Accra: In West Africa, under British colonial rule, Nnamdi Azikiwe starts a local newspaper, creating a forum for grievances—skirting sedition—to lay the groundwork for national independence. Azikiwe himself would eventually be Nigeria’s first president.

- 1968, Moscow: Poet and dissident Natalya Gorbanevkaya types out accounts of Soviet oppression in an underground system of publications called samizdat. These exposés reflect the sensibility of glasnost (openness), a sensibility that contributes to eventually undercutting the Soviet regime.

- 1992, Washington: A handful of young women, drawn initially to punk culture but eventually alienated by its hypermasculinity and not finding refuge in mainstream feminism, find and expand their tribe by creating hand-pasted zines, which grow to thousands of individual titles by 1993.

- 2011, Cairo: An Egyptian Facebook page created to protest a brutal beating death by the Egyptian police balloons to over 400,000 followers and contributes to rallying over 300,000 protesters to Cairo’s Tahrir square. Subsequent protests eventually lead to the toppling of Egyptian president Hosni Mubarak. (But the failure of the protests to evolve into real political power also shows the limitations of prominent social media platforms.)

- 2017, Charlottesville: Alt-right activists descend on Charlottesville, Virginia, for a march months in the making on Discord, a messaging platform originally established for gamers. Discord’s features for anonymity and decentralization make it ideally suited for out-of-view planning and deliberation.

- 2020, New York: During the early months of the COVID crisis, a private email chain named “Red Dawn,” among dozens of doctors and health and government officials, provided an encloses space for data-backed truth about COVID, away from the denials and obfuscation of the Trump administration.

- 2020, Minneapolis: In one month in 2014, there are only 398 tweets with #blacklivesmatter. This balloons to over a million per day by 2016, spurred by the multiple deaths of blacks at the hands of the police. But as in the other cases fomented by large-scale social media platforms, this groundswell does not translate into sustained change.

Principles of Successful First Acts

The first act of a social movement should accomplish a few significant goals. First, it should articulate a new norm for behaviours and circumstances. Communicating this clearly and sifting through drafts and iterations of a new norm require space and time. Second, the movement should recruit and align members. Not all are welcome, and some initial entrants to the movement must be excised. Third, it creates an organizational structure that can adapt to new lessons or inevitable opposition. A successful first act, then, establishes its vision, membership, and organizational agility.

Many of our digitized platforms intrinsically work against the conditions of privacy, enclosure, and curation needed to achieve success for the first act of movements.

Furthermore, in the successful examples of social change that Beckerman surveys, he notes several important conditions for the first act. It must be private. Radical ideas must be shielded from censorship or, at least, withering skepticism. This was easier to do pre-digitally with ink and physical doors rather than the default openness of the internet. It must be enclosed. Membership should be relatively small to begin and carefully managed to allow the interpersonal connections necessary for the accountability that drives group momentum. Finally, it is curated. Conversations are coordinated centrally, whether by editing a zine or deciding who is allowed to join in authoring a manifesto. By contrast, a Twitter thread can be a disjointed cacophony of one-upmanship.

Beckerman uses the metaphor of a table around which activists figuratively sit to do their work. The fact that digital platforms have become the predominant table of our age is, for Beckerman, cause for alarm. Many of our digitized platforms intrinsically work against the conditions of privacy, enclosure, and curation needed to achieve success for the first act of movements.

The Second Act: A Case Study

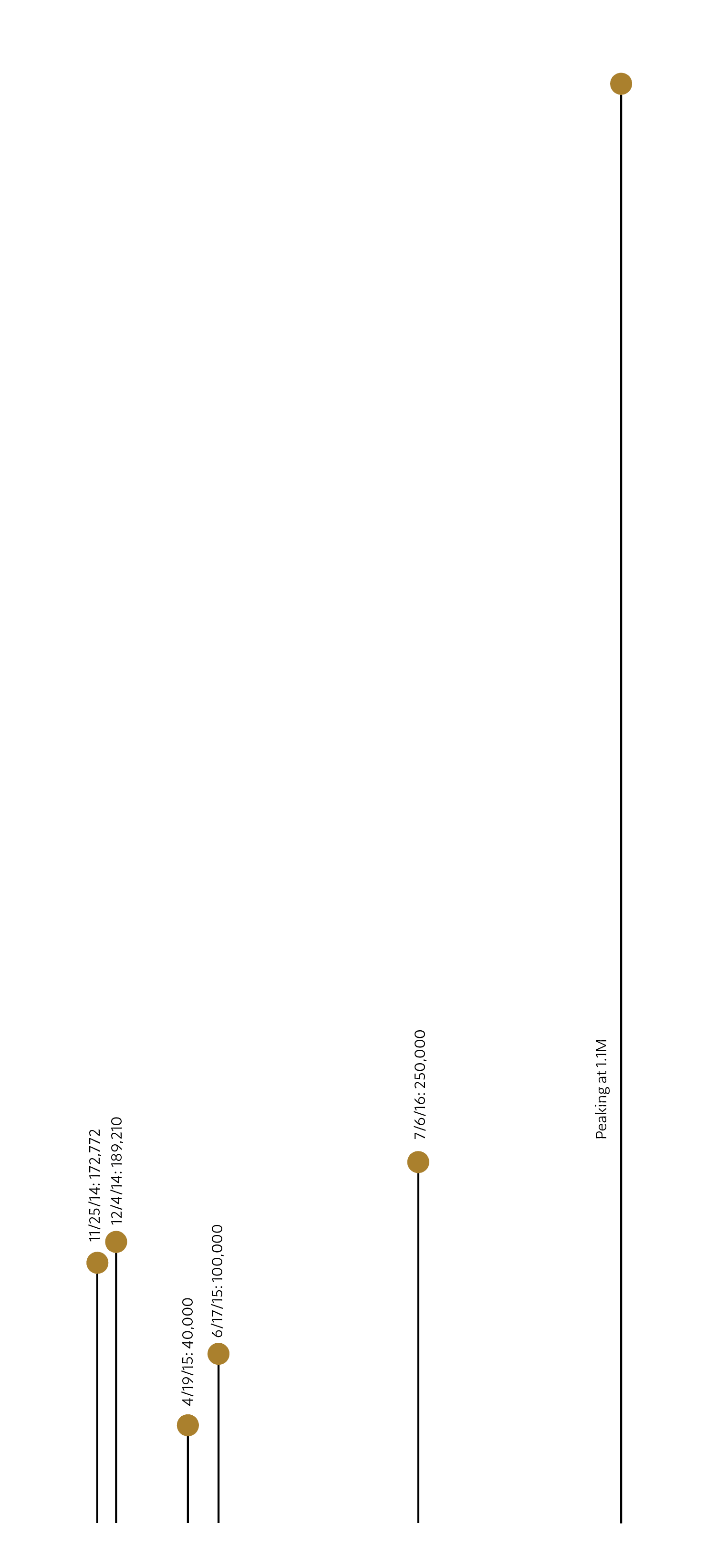

In 2014, #blacklivesmatter appeared in only about 400 tweets in one month, about a year after it was first coined. But soon, there were spikes, each time coinciding with a particular death (usually of a black man at the hands of police) or where a legal ruling fell short:

November 25, 2014: A grand jury fails to indict the police officer who killed Michael Brown, and a few days later, another officer kills twelve-year-old Tamir Rice—172,772 mentions of #blacklivesmatter.

December 4, 2014: Another grand jury fails to indict the police officer who killed Eric Garner in a choke hold—189,210 mentions.

April 19, 2015: Freddie Gray—40,000 mentions.

June 17, 2015: Emmanuel Church, South Carolina—100,000.

July 6, 2016: Philando Castile—250,000.

And onward to a peak of 1.1 million a day after other events.

The problem was that these spikes were part of a sawtooth pattern with lulls between the peaks—social media’s spotlight flits from spectacle to spectacle, outrage to outrage. BLM activists exhausted themselves trying to hold on to their spotlight as little changed institutionally and politically. Also, relationships frayed as airtime, instead of real change, became the commodity for which activists vied.

Relationships frayed as airtime, instead of real change, became the commodity for which activists vied.

In 2015, one activist group, Dream Defenders, quit social media for ten weeks after burning out from keeping up with social media. Beckerman quotes Rachel Gilmer, Dream Defenders’ strategist, about the lessons the social media hiatus taught her: “I think social media created a sense of false camaraderie among people. . . . We debated but in a petty way. What is the short quippy thing you can say about somebody else’s politics in 140 characters? But that isn’t strategy. And we didn’t get the space to do that.”

For Dream Defenders’ founder, Philip Agnew, the hiatus showed the difference between soft power—“a force that shapes culture through argument and story” and hard power—“the ability to lobby for legislation, elect sympathetic political leaders, get resources allocated toward your cause.”

Dream Defenders pivoted from public performance and “the race for followers” to local, in-person engagements, building “a constituency, as opposed to waiting for a moment of outrage.”

Miski Noor, a BLM activist, looked to Dream Defenders’ lessons after being exhausted by two years of nonstop protesting and little change. In 2016, Miski and six friends started the Black Visions Collective, pivoting from Black Lives Matter’s national-level mobilization to engaging in Minneapolis politics, partnering with the city council and the mayor’s office. Beckerman writes,

Miski and their friends got to know city council members and their aides, inundated them with research material, visited their offices, and, maybe most important, brought people out to hearings when the budget was being discussed, arguing in forum after forum against the belief that all the police needed were a few more bodycams. All this happened without much fanfare and largely off-line.

When George Floyd was murdered on May 25, 2020, the BLM movement exploded, with an estimated twenty-six million people participating in protests within a month. But Miski, after three years of working on “hard power,” didn’t engage in large protests. Instead, Black Visions continued their discipline of lobbying city leaders individually to turn the “soft power” amplified by the nationwide protests into a real victory. By December 2020, the Minneapolis city council voted to funnel 4.5 percent of the police budget into the Office of Violence Prevention to pay for mental health professionals to respond to situations that otherwise would have been handled by the police. This was eight million dollars; the annual funding had never exceeded a million dollars in prior years.

The Third Act of Lasting Change

Most movements do not advance beyond the second act of public revolt into the third act of real change. Often this is because activists do not organize for sustained power and do not work with established institutions. Martin Luther King Jr. wrote, “A social movement that only moves people is merely a revolt. A movement that changes both people and institutions is a revolution.” President Obama was more pointed in 2018: “Once you’ve highlighted an issue and brought it to people’s attention and shined a spotlight, and elected officials or people in a position to start bringing about change are ready to sit down with you, then you can’t just keep on yelling at them.”

Ideological purity and its related siren, insularity, create conditions for movements to falter.

Sometimes a lack of engagement is due to inexperience; yet it can also be from the shadow side of taking the moral high ground. Ideological purity and its related siren, insularity, create conditions for movements to falter. John Ehrenberg, a political science professor, wrote about the failure of Occupy Wall Street as a case in point:

Renouncing political activity in the name of ideological purity can have no other effect than to drive people back into the arms of the status quo. A fundamental conceptual error lay at the heart of OWS’s (Occupy Wall Street) mistake. . . . It failed to recognize that the political system that had helped produce the problem in the first place was also the path to a resolution.

While Beckerman recognizes the need to engage institutions of power, he does not offer as many helpful prescriptions for third-act change as he does for the first act of incubation. He seems resigned to history’s “relay race” where a radical idea “incubated in one place and time [is] revealed nearly a hundred years later.” Or lamenting that many activists suffer the martyrdom of futility: “In some cases, the movements that seemed promising are then undermined over time, obscuring the breakthroughs they once represented.”

Of course, there are other guides who should be read alongside Beckerman. One example is Ivan Marovic, who helped topple Yugoslav president Slobodan Milošević. Marovic’s book The Path of Most Resistance surprisingly does not read like a memoir from a front-line activist. Rather, it reads like an ivory tower tome, including dozens of templates on strategic planning, SWOT and stakeholder analyses, and workshop plans. The fact that a hardened activist leader like Marovic would see it necessary to plan a revolution as an MBA might plan a startup demonstrates that turning a revolt into a revolution requires planning over furor.

Why We Are All Activists

Beckerman’s book adds to a wide curriculum of how social movements work, particularly by carefully addressing the first act, in which important foundations are laid in quiet planning. A cacophony of digital platforms often dilutes this first stage.

But beyond historical curiosity, why should many of us bother with how movements work if we are not actively coordinating them? Perhaps it is because we are pulled into movements more than we might realize. A ribbon, a weekend march, a donation, or a petition gives us a fleeting high of solidarity, but these are largely hollow, consumerist second acts. Beckerman gives his own example: “In the weeks after Donald Trump’s inauguration, I found myself at protests nearly every weekend. . . . I’ve never been for demonstrations. . . . It was good to be with other people. . . . But it also occurred to me, in a moment of cynicism or clarity, that everyone around me was incessantly posing for their camera phones.”

What, if anything, were these protests accomplishing in terms of real social change? Movements have been and will continue to be a necessary part of civilization’s progress because the tendency toward stasis and inequity can only be disrupted from outside. But for that disruption to last requires all of us to go beyond the spectacle of the protest and to be students of the quiet before and the work after.