I

If anyone causes one of these little ones to stumble, it would be better for them to have a large millstone hung around their neck and to be drowned in the depths of the sea.

—Matthew 18:6

I didn’t want to talk about gender for a long time. Some lucky alchemy of when I was born, nuanced role-modelling, fierce love from my dad, and deep dignity in my mom imparted an understanding that to be a woman in full was simply to be robustly human. I understood femininity to be a lush expression of what it is to feel deeply and strive valiantly, to fulfill a multitude of roles with class and grace, to delight in the created order and all the methods humans had devised—were still devising—to understand and steward that order. And I understood masculinity to be a different expression of the same fundamental impulses—both casts equal in brilliance, both fascinatingly diverse in their cultural shape and in the comportment of individual men and women.

Fresh out of college, I moved to Washington, DC, a city where “show don’t tell” is, apparently, an inconvenient proverb. Here, even the most subtle aspects of life seemed to get recruited into political cause. I remember arguing with conservative friends that, no, we didn’t need a movement to “recover femininity in American life” (which always seemed premised on suspiciously Southern norms), but rather that as women we just needed to live fully into every sphere, and that “femininity” in its many expressions—like masculinity—would naturally follow suit. Progressive colleagues also found me confusing: I would host lefty bandmates for musical rehearsals and surprise them with my delight in domestic life, the cooking, cleaning, flower-arranging, and so on an additive to joy and communion with others, not a step back into servitude or Betty Friedan misery.

Looking back now at how relatively free I felt as a Christian woman making her way in relationships, career, secular milieus, and sacred canopies, I think I was taking for granted the gift of unusually considerate family formation and, crucially, love layered across generations shaped by cross-cultural encounter and exchange. My parents, culturally astute people of faith, had protected me from the more suffocating gender expectations of American evangelicalism, even as they’d questioned the more destructive orthodoxies of second- and third-wave feminisms. I entered the real world naive, but healthy. It seemed counterproductive to make gender—and in my case, being female—a protagonist in human grievance; I told myself never to stoop and play that card.

The foils to my personhood began to highlight a distinctively female shape—one that I was experiencing as both thorn and gift, vulnerability and power.

Then some bruising began. The first reported feature I ever wrote—about shifts in voting patterns among Asian Americans—was hacked up by a conservative magazine seeking to use people and their compellingly nuanced patriotism for a crass political end. Later, a book manuscript went through similar treatment, when what would become The Fabric of Character was initially rewritten into a didactic expression of a good-old-boys formula for Wasp morality. In the workplace I witnessed inappropriate overtures from men toward their female colleagues, and women’s kowtows to Sheryl Sandberg’s Lean In definition of success—“you must strive to be a company executive”—made too many of them exhausted and, more often than Sandberg could ever have wanted, self-berating. I noticed a fierce defiance in women who had come of age in the sixties and seventies, their open bragging about how many abortions they’d had obscuring a tenuous hold on control. Fast-forward to my own marriage and multiple miscarriages, an unexpectedly public vocation and its struggle to communicate clearly in an intellectual arena still dominated by male referees, and the foils to my personhood began to highlight a distinctively female shape—one that I was experiencing as both thorn and gift, vulnerability and power. I began to wonder if there was a way to double down on my commitment to dignifying all men and women by sowing the conditions for wholeness in their sharing of this world, but to do so, with quiet mischief, as a woman. And I wondered if this might not be the best century to try.

When Gift Becomes Threat

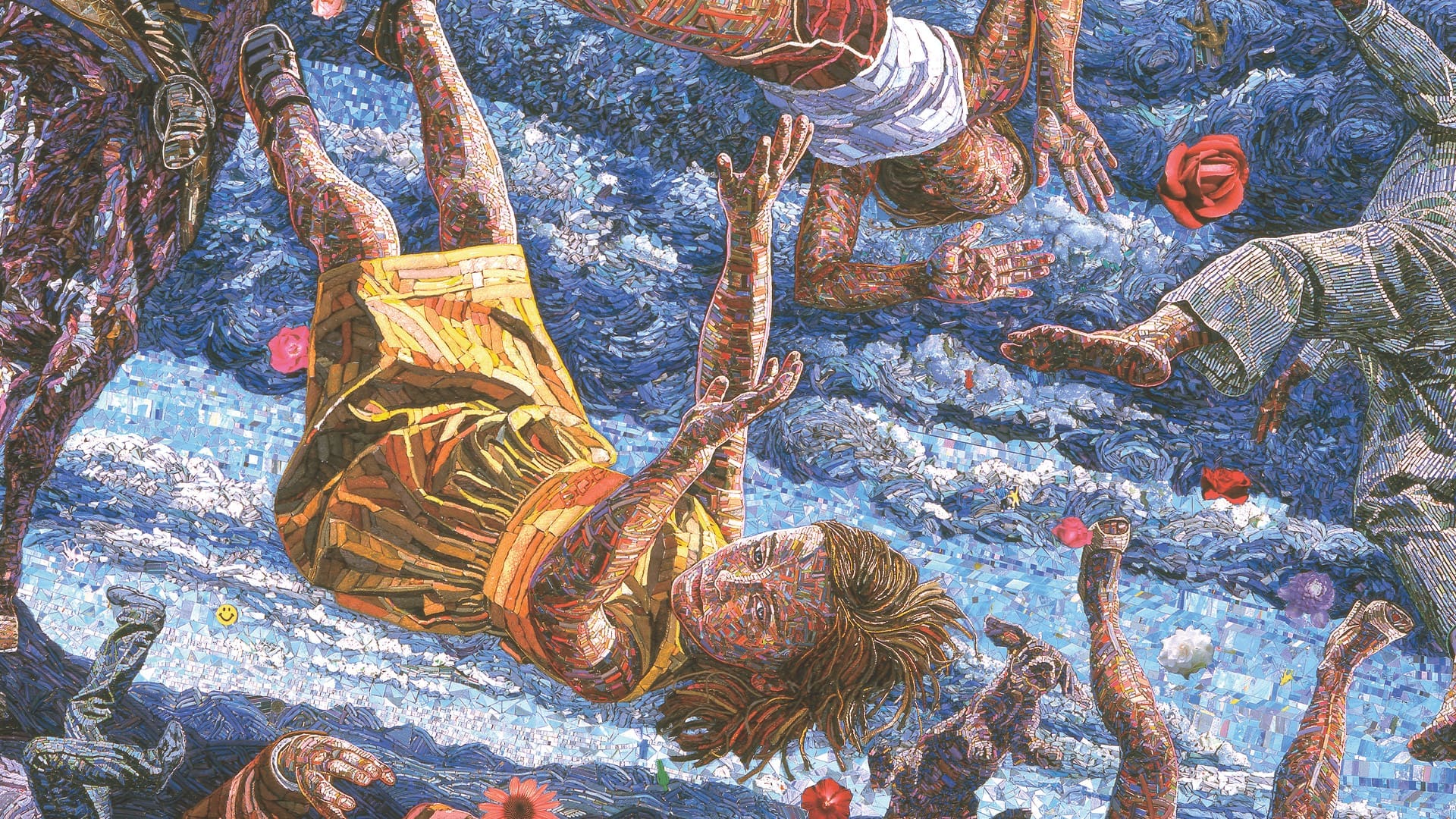

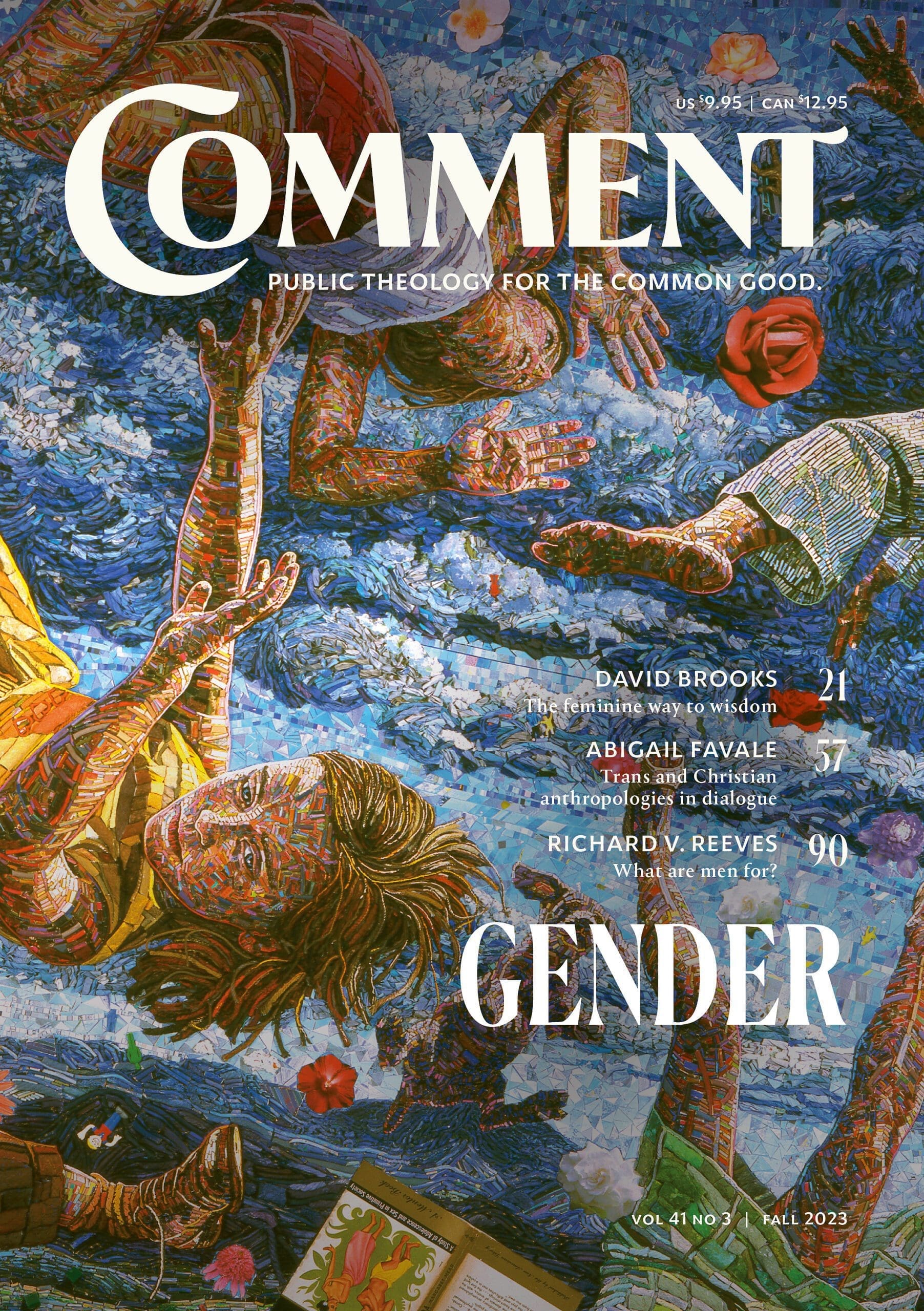

This instinct, that there may be something right now petering out in male-shaped systems that might be revived and remade by welcoming a feminine logic, has collided with a fierce maelstrom of gender politics. The piece we have chosen for this issue’s cover, 9.81 Meters per Second per Second, by Mary McCleary, evokes the disarray: children in free fall suspended above dazed and defeated adults, each figure eerily adrift, each at the mercy of an accelerating gravitational pull. It’s a picture, for me, of this pathologically Western moment as our disintegrating culture thrusts its talons into yet another aspect of our created design—in this case the unity of body and soul as expressed in one’s maleness or femaleness. And I must state what I see: We are losing to chaos, a chaos of meaning and of personhood.

It doesn’t take much to be discombobulated by the different streams of data flowing into one boiling cauldron. For starters, the boys are not all right. They are outperformed by girls in most academic disciplines, they are more likely to feel socially excluded, boys raised in poverty are less likely than girls to escape it, and all are tossed about by prohibitions on “toxic masculinity” without recourse to a positive vision for healthy masculinity. Meanwhile girls’ interior lives are suffering: The Centers for Disease Control found that between 2009 and 2015, emergency-room admissions for self-harm among ten- to fourteen-year-old girls had tripled, and that in 2021, nearly one in three high school girls had considered suicide, a 60 percent increase since 2011. Separately (though simultaneously), between 2013 and 2020, girls between the ages of thirteen and seventeen seeking mastectomies increased thirteenfold. Rates of adolescent gender transition have skyrocketed, with the number of boys and girls seeking medical intervention having risen 3,600 percent over the last decade. The surge most pronounced in patients was between the ages of twelve and eighteen. Forty-two thousand children and teens across the US were diagnosed with gender dysphoria in 2021, nearly triple the number in 2017.

Where are the adults? As these dramatic trendlines have shot up, our culture’s only mechanism for imposing some form of “order” seems to be the English language. Elite institutions and their progressive consensus have returned to familiar tactics: Impose new verbal rules without warning or a clear telos, bend reality whenever necessary to conform it to the whims of that ever-shifting consensus, and prop it up and proclaim it universal. Comment has covered these dangers previously in our Beyond Ideologies issue; the devil may find new terrain, but his devices are ever the same.

Now, I understand that every generation wants to find its “thing,” its scene, a new level of probing the boundaries of life’s possibilities to set it apart from what the previous generation accepted as reality. And there’s no denying that Gen Z has done away with some of the more straitjacketing stereotypes that Christians should have done away with long ago. But the solution that our culture is offering, the so-called positive vision of valuing souls as the drivers of our bodies, which are mere instruments on which to express one’s freedom and felt identity, is inescapably gnostic. It should not go unnoticed that this ideology has gained rapid entrée into the courts of polite consensus precisely when we’ve never been less physically present to each other, to ourselves, or to the earth. When seven hours of the average person’s day is spent on a screen, with a limited if emotionally powerful toolbox of words and images, it’s no wonder that a disembodied reality finds so much purchase among us. Except that this fantasy is not constrained to the screen: its technologies are not merely digital but surgical and chemical, doing violence to bodies, to psyches, to families, and to public squares. And the serpent once more is singing.

Unearthing

This issue of Comment is taking a cultural risk, shaking up the conversational Boggle board on gender not for the sake of subversion or transgression but so that people of faith might be reoriented toward that which is real, fleshly, human, and true. What our authors have wound up knitting together here and online is a shimmering iconography of masculinity and femininity, one that goes back to the Jewish origins of our faith, that dwells for an important spell with the Holy Family, that interrogates ancient origin mythologies in the shadow of today’s self-making ones, and that celebrates the many different ways in which we each learn to be human, in part, but crucial part, through the burdens and blessings of our given sex. This is an issue that, contrary to what our progressive friends are taught to assume, affirms the created goodness of male and female. And it is an issue that, contrary to what our more conservative friends might be comfortable with, acknowledges that the divine purpose for reality often includes overturning our received assumptions about how the gifts of maleness and femaleness manifest themselves in our common life. We believe this issue can and does do both, because in it we are seeking to do what we at Comment are always seeking to do: to rehumanize our age, to respond with compassion, to nourish our collective longing for wholeness and belonging, order and freedom. And to do so without reactivity, but with personalism, imagination, and the honest ache of the now and the not yet.