Police, Pirates, And Protest| I was firing up the grill on Mother’s Day when I heard loud shouts and feet pounding down the sidewalk. I turned to see a police officer huffing and puffing in pursuit. By the time I got to the front of my house he was standing on the back of a suspect, coiling his arm behind his back while the collared man protested, wheezing, gasping. Unfortunately the scene felt all too familiar—like ones I’d seen replayed in cell phone videos in the news. My heart was in my throat; the spate of bad news of late taught me how quickly this could become tragic. As a sure sign of the times I noted others quickly approach, their phones raised, fumbling for the “record” button.

It would be unfortunate if Christians assumed that being on the side of “law and order” meant a default defense of policing tactics. Indeed, the legacy of Christian social thought has long been attentive to the failure of authority to live up to its responsibility for the commonweal. Consider, for example, Augustine’s ancient indictment in his City of God: “Remove justice, and what are kingdoms but gangs of criminals on a large scale?” He goes on to recount an exchange with contemporary relevance:

[I]t was a witty and a truthful rejoinder which was given by a captured pirate to Alexander the Great. The king asked the fellow, “What is your idea, in infesting the sea?” And the pirate answered, with uninhibited insolence, “The same as yours, in infesting the earth! But because I do it with a tiny craft, I’m called a pirate; because you have a mighty navy, you’re called an emperor.”

There is mounting evidence of serious, systemic problems with the culture of police departments in too many North American cities, mirrored by systemic discrimination in prosecution and incarceration. If we are going to be attentive to inequalities, surely the inequitable administration of justice and use of force calls for response. To demand a systemic “culture shift” in policing is not the cry of radical anarchy, it is the plea and prayer of those who long for justice.

Our friend and Comment reader, Kyle Bennett, recently pointed us to similar observations made by Abraham Kuyper over a century ago. In his political manifesto, Ons Program (recently published by the Acton Institute as Guidance for Christian Engagement in Government), Kuyper’s concern with “the social question” turns to questions about the police, identifying a different sort of 1 percent: “A good police force,” he comments, “must be respected by 99 percent of the population as the guardian of peace and should be feared by no more than the 1 percent who are difficult and obstinate. All classes and segments of the society should know they can count on the police.”

But this is not a license for the status quo or a knee-jerk defense of “law and order.” To the contrary, Kuyper sees scenes that sound like Ferguson and Baltimore: “[O]ur police today are nothing like this. One could almost say that in an evil hour they have developed into a sort of Praetorian gang with a military organization that creates unrest in the spirits of the citizens, stimulating—even provoking— them to rebellion.” And he doesn’t shy from seeing this as a class struggle: “In particular the class from which most of our workers come appear to the police as an inferior lot who need to be kept under the masters’ thumb.”

“This,” Kuyper concludes, “has a very destructive effect.” Such experiences of capriciousness and inequity in justice and security only breed suspicion of government and even justice itself. And as Kuyper notes, it creates corrosive sympathies between genuine law-breakers and those unjustly downtrodden by the system. Those of us who care about the renewal of social architecture should be passionate advocates for renewal and reform in policing. In so doing, we’ll be drawing on 2,000 years of Christian social thought.

Reform As Design | Such aspirations of reform bring to mind an insight from the remarkable polymath, Herbert Simon: “Everyone designs who devises a course of action aimed at changing existing situations into preferred ones. The intellectual activity that produces material artifacts is no different fundamentally from the one that prescribes remedies for a sick patient or the one that devises a new sales plan for a company or a social welfare policy for a state.” Designers, then, are those who aim to change existing situations into preferred ones—which sounds like pretty much all of us! Culture-making is a mode of design. We’re all designers now.

The aesthetic resonance of the word “design” is a unique way to frame all of our cultural energies devoted to reform and renewal, the work of changing things from the way they are to the way they ought to be. Reform is a design project, which means that all work of cultural renewal has an aesthetic aspect to it. We’re working with materials and environments, shaping ways of life that are real and embodied, hoping to bend the world-as-wefind- it toward the world its called to be.

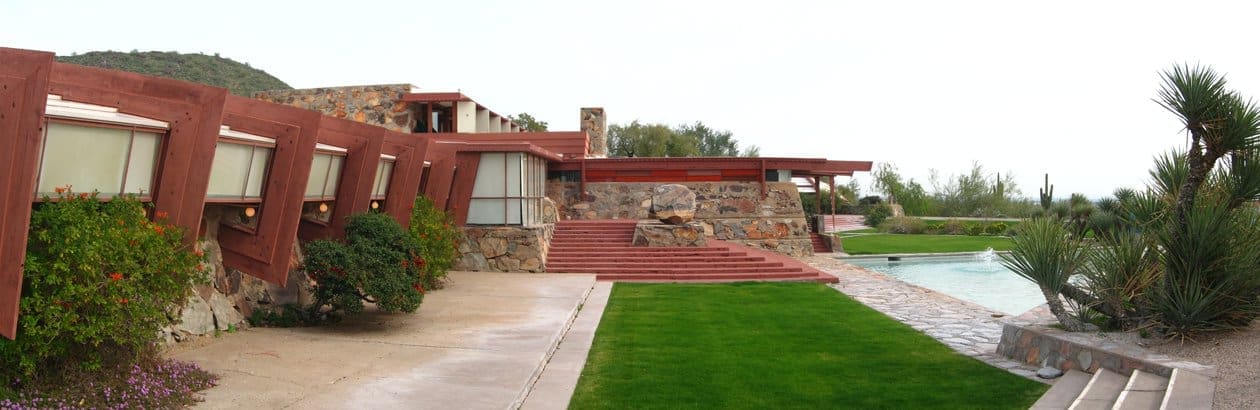

This “design” approach to the renewal of social architecture is tangibly illustrated in an anecdote from the world architecture proper. The story is recounted by Matt Taylor, a student at Taliesen, Frank Lloyd Wright’s architecture school. Looking back on Wright’s affordable houses he called “Usonians,” Taylor recalls:

During my time at Taliesen, I was able to talk to many owners of Usonians. They talked about their environments with unreserved passion. It was from one, Mrs. Pew, that I learned the true secret of Mr. Wright’s genius and success. She described how at first she hated the house. She felt that Mr. Wright had not listened to her requirements but merely built what he wanted. She was, at the end of her second year living in it, ready to sell it and move on—at great financial sacrifice. She told me that she decided that she would “give the house another year without struggling with it” before she made up her mind. In that year, a transformation took place. She discovered that “Mr. Wright had not built a house for who I was”—but “for the person I could become.”

When we aim to change existing situations into preferred ones, we are also hoping to change who we are and how we are. We are designing for life.

Educating Designers | I recently had occasion to visit Taliesen West, the winter location of the Frank Lloyd Wright School of Architecture in Scottsdale, AR. The tagline of Wright’s school is “building architects,” and what fascinated me was not just the buildings but his philosophy of education. How do you make a maker? How do you design a designer? How do you, well, build an architect?

If these architects were going to “change existing situations into preferred ones,” they first needed an intimate acquaintance with the way things are. So Wright’s school of architecture had a very hands-on beginning: the first students actually built the school. Wright believed you couldn’t know how to respond to the materials until you had put your hands on it; you couldn’t design for an environment until you had inhabited it. So Wright and his students (and his family) pitched their tents in the middle of the desert and dwelled there, putting their hands on the place before putting their hands to work. Even to this day, these architectapprentices build their own residences for their time at the school. This was a tangible expression of Wright’s twin ideals of “organic” architecture— architecture that grew from its surroundings— and hands-on apprenticeship.

There is another lesson for the renewal of social architecture here: we don’t come with our blueprints and impose upon the world as we find it. We can’t just have our eyes on the plans; we need to listen to the groaning of creation. We need to dwell in places of heartbreak and hopelessness. We need local knowledge.

But we also come with conviction, with a vision that isn’t our own invention but is one we’ve received from the Creator of all things, a sketch of how things ought to be. The work of building social architecture is a dance between the world-as-we-find-it and kingdom-come, the way God wants the world to be. If we can play a part in (re)designing our world, the best we can hope to hear is a testimony like Mrs. Pew’s: “You’ve built a society for the person I could become.”

Graduation And Good Work | One can imagine the sorts of architects who would graduate from such a program. If you were pursuing architecture to just feather your own nest, the idea of building your own shelter in the desert is not an experience you’d likely sign up for. It raises fundamental questions about the ends of education. What does a formative education look like? And what do our educations teach us to aspire to?

We have just come through that season in the academic calendar where the aspirations of graduates are distilled in a thousand commencement speeches across the country. These are mostly strings of forgettable platitudes layered between worn clichés uttered by people who have some sort of celebrity cachet. And most of them do very little to rock the boat of the status quo understanding of education as a credentialing hoop to jump through on the way to making money. And many students largely hope to graduate in order to merely climb the ladder of prosperity.

Against this backdrop, I was struck by the story a friend recently shared about a true artisan who had no interest in “graduating” to something else. George Yeoman Pocock was a master shell builder, crafting the sleek sculls that rowing teams use. His story is part of Daniel James Brown’s remarkable book, The Boys in the Boat: Nine Americans and Their Epic Quest for Gold at the 1936 Berlin Olympics. As a result of various contingencies of circumstance, Pocock acquired a wealth of stock that could easily have made him independently wealthy, releasing him from his work as a shell builder. But he had no interest in “graduating” from his manual labour. It’s not that he lacked ambition; it’s precisely because his ambition was so precise: “My ambition has always been to be the greatest shell builder in the world,” he said; “and without false modesty I believe I have attained that goal. If I were to sell the stock, I fear I would lose my incentive and become a wealthy man, but a second-rate artisan. I prefer to remain a first-class artisan.”

Share this vision with the graduates you encounter this summer. Remind them of the riches that come from being a master artisan. Encourage them to set their sights on becoming the men and women they were made to be. Paint pictures of the joy and delight and peace and content that comes with nestling into your calling. And maybe give them a subscription to Comment magazine for the journey!