The finest culture ages well: wine, books, carvings, cheese, scotch, music, and thought. Stonework is one of the best ways for me to contribute to culture in a way that will age well. I work as a mason in a family business during my summer months, and I thoroughly enjoy it. Some mornings, when I’m working alone, I show up to the job site at 7:00 am and begin chiseling stone in the cool of the day. I get to select a stone from a pile, think of a good place in the wall for it, and begin shaping it. The shaping work needs to be careful, rhythmic, and patient. Each stone has hidden fracture lines that, when agitated, can turn a potentially great rock into broken waste. The rhythm in which I set my chisel in place and hit it with the hammer is not so much set by me as lived in. Attempting to stop the hammer mid-swing is never a good idea, so it’s very important to be patient, carefully placing the chisel on a flat face that will transfer the hammer’s energy straight down into the stone and hopefully break off a chip to reveal a brand new face, known only to me and God.

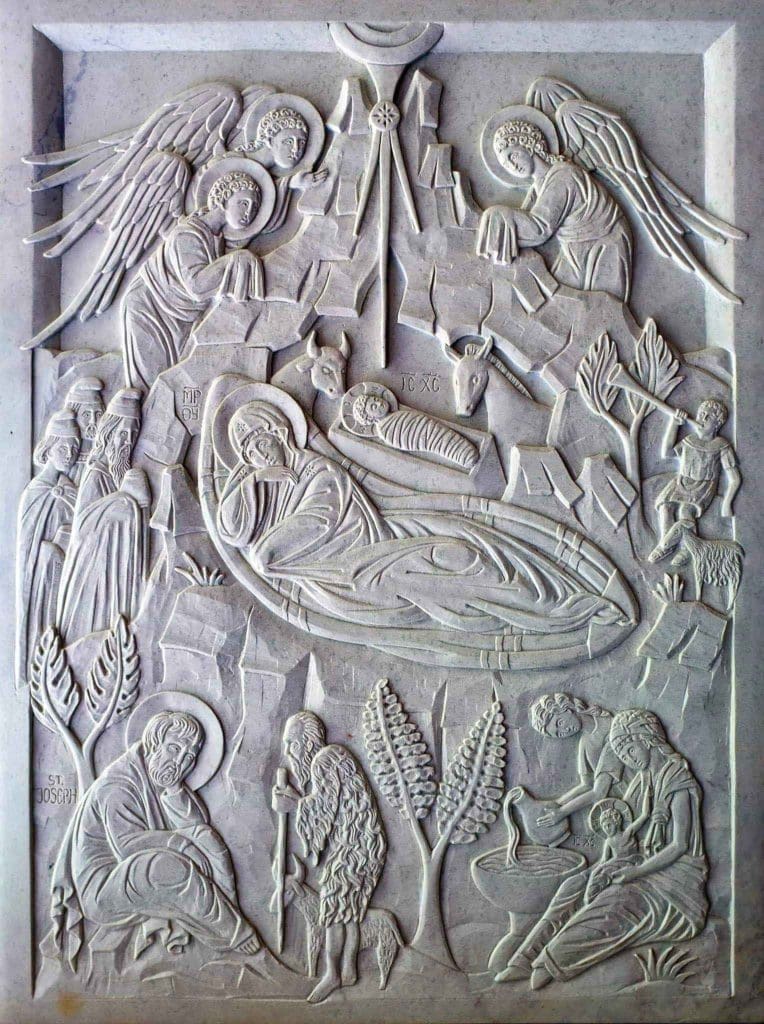

Photo: Ben Bouwman |

I shouldn’t romanticize masonry, though. These quiet mornings rarely occur, and even when they do, they normally last for all of two minutes before I have to fire up the gas-powered saw, which makes enough dust and noise to wake up the neighbourhood, scare away the birds, and jar me out of my appreciative morning musing. Good stonework doesn’t result from this kind of thinking anyway. It usually comes as the result of good natural material, good planning, and a slowly-developed knack for shaping the rocks.

Even though natural stone is always an enhancement to the architecture of a place, it can be done very poorly. Since the advent of huge saws, stone from quarries can be cut so that the top and bottom are flat and exactly parallel. Sawn stone allows the mason to work very quickly, since each rock is pre-shaped and can be easily transported by forklift. Large landscape companies, with multiple crews of masons, usually use this type of stone even though it costs more than naturally-occurring stone, because it is so quick to install. The earth becomes nothing more than a product, which can be shipped and installed mechanically. Some companies even ship stone from China and India, where it can be processed more cheaply than in Canada. The quarry workers and the mason become machines which, when paid minimum wage, can make money for the company by installing “distinctive landscapes” at breakneck pace. These companies are like speeding drivers at night who are traveling too fast to stop for whatever may appear in their headlights. As a result, workmanship disappears and pollution increases.

There is an opposite extreme to this type of abomination of craft and artistic creation. Landscape Artist Lew French produces the most stunning fireplaces and stone walls I have ever seen. He sources his material locally, using stone he finds from the property itself or reclaims from old buildings. This means that his material does not need to be shipped across the planet, an obvious benefit. It also means that the stones tell the story of the particular place where they are to be laid before they are even used. French does not use exposed mortar or shaping tools either, because he believes that each stone should speak for itself. His technical abilities are precise, and he is able to take what seems to be rubble and make it into excellent masonry.

I am deeply impressed by what French is able to accomplish without power tools or even a hammer and chisel, but I am somewhat critical of his thought about stone, since he believes that something is inevitably lost when humans begin shaping their world. My favourite part of Herman Dooyeweerd’s otherwise daunting New Critique of Theoretical Thought is the way he describes the complex relationships within which cultural artifacts come to us. Instead of making French’s clear opposition between Nature and Culture, Dooyeweerd helps us to see that culture comes to us interlaced with the original, created stuff we normally call nature. What makes this thought so exciting for me is that Dooyeweerd explains it in terms of a marble statue of Hermes and the boy Dionysus, carved by Praxiteles in antiquity. For the sculpture to work, it obviously requires marble. The stone is the basic physical component of the piece. However, Hermes and Dionysus are the result of Praxiteles’s intent and skillful work. Balance between good material, artistic intent, and carefully developed skill is essential if, as Rilke reminds us, the piece is going to dazzle us, see us, and in the end call to us: “You must change your life.”

If Dooyeweerd is right about culture, interlacement of created material, formative power, and intent can only happen when we, like Lew French, choose to respect stone as given to us as part of God’s good, local, entrusted-to-our-stewardship world. But in addition to stone, art, and stewardship, God has also given us economy and technical skill and tools. For the marble in Rilke’s “Archaic Torso of Apollo” or Praxiteles’ “Hermes and the Boy Dionysus” to shake us and demand that we change our lives, it needs to be shaped. The raw block of marble cannot speak to us as the sculpture can. With tools, shaping, and intentional development, sculptures and stone walls come alive.

I cannot pretend to have either the artistic skill of Lew French or the economic success of a large landscaping company. But at my work, we aim to achieve both by long repetitive practice, with many blows from a hammer and chisel and much patient working with good material. We try to match the look of each job to its cultural and implaced story, so that new buildings in old areas look old and new buildings in new areas look new. Our struggle, day after day, is always to bring out the created potential of the rock well without overwriting the created beauty of the earth. Work in this middle ground makes life-giving stonework and good places and thankful masons.