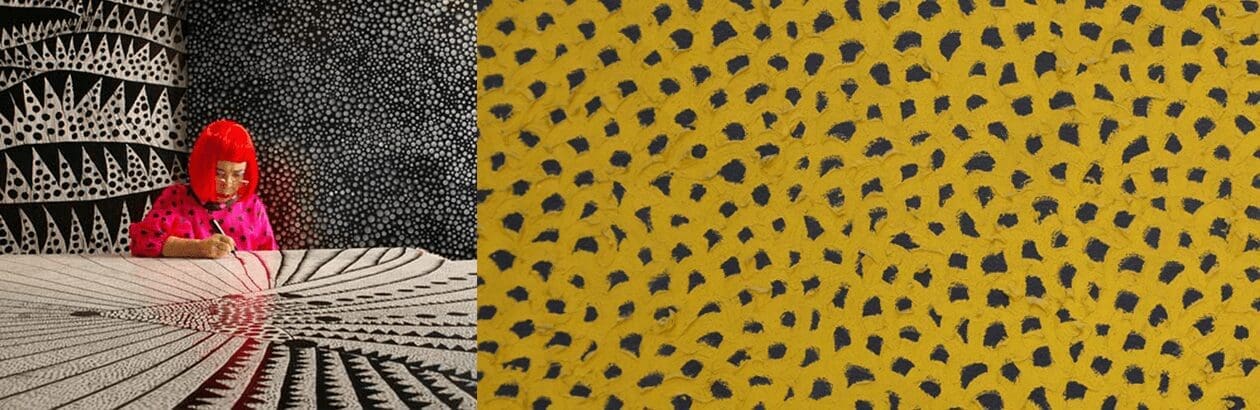

Yayoi Kusama, now 80 years old, remains one of the most eccentric and elusive figures in the contemporary art world. Although her Å“uvre is varied and uneven, Kusama’s best works—an ongoing series of paintings called “Infinity Nets”—may be among the most visually complex and conceptually provocative paintings being created today.

Kusama described her Infinity Nets as paintings “without beginning, end, or center. The entire canvas would be occupied by [a] monochromatic net. This endless repetition caused a kind of dizzy, empty, hypnotic feeling.” These “nets” are an accumulation of connected, though individually applied, crescent-shaped brush strokes of thick paint. Generally, these marks curve in the same direction while gradually shifting up, down, left, or right. They compose themselves into congregations that swell and ebb across the painting. These groups of unique gestures are organized around points of tension and release. The closest comparison to their structure may be found in nature, where visible matter clusters around invisible points of gravity. The result is a design that is neither random nor systematic. Kusama’s Infinity Nets remind one of a river in which the rise, fall, and direction of the glistening surface is shaped by the topography of the riverbed.

This diffusion of opulent monochrome paint across the painting is systematically interrupted by small openings in the net, organic variations of circles and ovals through which the underlying canvas is manifested. The crux of the Infinity Nets is the literal and perceptual exchange between the materiality of the painted net and the pictorial space behind or caught within the net.

A 1959 essay by Donald Judd, who was at the time a critic for ARTnews, may still be the most succinct analysis of Kusama’s Infinity Nets; he wrote, “the effect [of Kusama’s Infinity Net] is both complex and simple. Essentially it is produced by the interaction of the two close somewhat parallel planes … at points merging at the surface plane and at others diverging slightly but powerfully.” This interaction between the background and the “net” of Kusama’s paintings causes the work to oscillate between the infinity of pictorial space and the presence of the material surface. In the best examples, the Infinity Nets hold these divergent paradigms in an inseparable equilibrium.

Kusama participates in a tradition of the sublime expressed in abstract painting. Judd notes, in passing, that Kusama’s Infinity Nets share aesthetic and spiritual affinities with Abstract Expressionism. Kusama’s Infinity Nets emerged in the late 50s as Abstract Expressionism was both triumphant and waning. In the work of an artist like Willem de Kooning, the gestures are grand, boisterous, unique, and directional. They are repositories of bursting energy. By comparison, Kusama’s gestures are unpretentious and repetitive, without relinquishing their individuality; yet, collectively, they build and generate energy latent in the material paint and capture (remember, these are nets) light. The Infinity Nets shift from pictorialism, in which a painting suggests a vicarious experience, to a more direct perceptual experience. This process draws the infinite into the imminent.

|

In November 2008, a white-on-white Infinity Net painting was auctioned at Christies in New York for $5,794,500. That became the highest price paid for a living female artist. The work, simply entitled No. 2, was not a particularly outstanding example of Kusama’s Infinity Nets. For better and worse, No. 2 manifests Kusama discovering her own process. In contrast to the steady pattern of growth and entropy that makes the best of her Infinity Nets read as obsessively unified, the “all over” optical field of No. 2 is broken into starts and stops. No. 2 was created in 1959, the year that Kusama initiated the series, and the fact that the work had been owned by Judd certainly increased this particular work’s price.

Kusama arrived in New York from her native Japan in 1958 and she quickly became a well-known figure in the art world, as notorious for the happenings that she staged as she was celebrated for her paintings. The following decade was a prolific period for Kusama in which she would paint expansive Infinity Nets for uninterrupted sessions of 40 to 50 hours. In 1973, Kusama returned to Japan and disappeared from the art world as quickly as she appeared. In 1977, Kusama, who has had hallucinations since childhood, was diagnosed with “obsessive neurosis” and voluntarily entered a psychiatric facility where she still lives. A 1998 retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art introduced Kusama’s work to a generation of artists who were indebted to her art without knowing it. She had opened up a creative space that other artists had filled in her absence.

Last year’s record-breaking sale thrust Kusama’s work, which had been relatively absent from the art world for a decade, back into the spotlight. She currently has a one-person show at the Gagosian Gallery’s flagship space on 24th Street in New York, arguably the premier gallery in the world. The show features several recent Infinity Nets, a few of which are better paintings than No. 2. Three examples in particular highlight the subtle, but significant, diverse directions in which Kusama’s Infinity Nets have matured.

|

Infinity Net TWPPQ (Kusama distinguishes these Infinity Nets by a sequence of letters that are neither descriptive nor symbolic) is a white-on-white painting of 2008. As she had done with No. 2, Kusama first painted the entire canvas black. Then she repainted it with a wash of white paint. The effect of this is not a static field of gray but rather a constantly shifting space, of indeterminate pictorial depth, between the black and white. Over this ground, Kusama has placed the repeating marks of white. Even more than No. 2, Infinity Net TWPPQ demonstrates the subtle and compounding relationship between the net’s material density and the ground’s atmosphere.

|

Infinity Net TTOOX, 2009, is a black-on-black painting in which Kusama boldly obliterates all pictorial space and confronts the viewer with the stark materiality and lush opticality of the paint itself. The painting’s square format establishes an iconic stillness. What allows us to read the painting as something more than an expanse of darkness is the fact that the impasto of each brush mark picks up the light, both natural and artificial, of the gallery space. As this light condition changes over time, various aspects of the painting’s surface assert themselves.

|

Infinity Net QZAAL, 2009, is a gold-on-blue painting. Compared to Infinity Net TWPPQ and Infinity Net TTOOX, Infinity Net QZAAL is the most visually stunning but it may also be the least interesting. In this work, Kusama has painted dazzling gold marks onto a flat or static blue background. Because blue optically recedes from the plane of the canvas’s surface and the gold optically and literally floats on the canvas’s surface, Infinity Net QZAAL comes as close to a pictorial trope as any of her Infinity Nets. Infinity Net QZAAL‘s effect, in contrast to Infinity Net TWPPQ and Infinity Net TTOOX, is more theatrical than spiritual. The painting becomes about infinity, symbolized in gold and blue, rather than a material transubstantiation of material into spirit.

The publicity surrounding No. 2‘s sale inevitably raised questions of Kusama’s contribution to the history of contemporary painting. While it is premature to judge her work definitively, the crux of this assessment process seems to rest in this question: Are Kusama’s Infinity Nets merely theatrical gestures of a relentless ambition or they are aesthetic and conceptual challenges to the history of contemporary painting as it attempts to make the invisible visible?