I

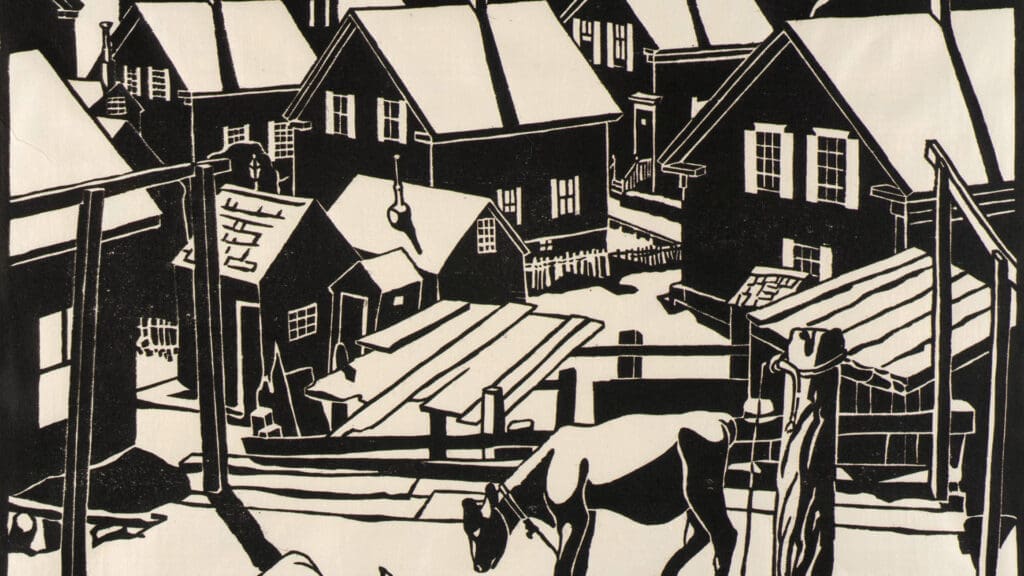

In Oscar Wilde’s novel The Picture of Dorian Gray, the titular Dorian begins as a beautiful young man, adored by society and shaped by the gaze of others. A friend of his, the painter Basil Hallward, paints his likeness with a kind of reverence, as though Dorian’s face can carry an entire moral vision. Then a friend of Basil’s arrives, the brilliant and persuasive Lord Henry, who offers Dorian a catechism for a life built on image, pleasure, and immunity from consequence. Dorian, convinced that his appearance is his highest good, wishes that the portrait would age in his place so that he may remain pristine. His wish is mysteriously granted.

From that point forward, Dorian lives a life of indulgence, vanity, and hidden cruelty, while the painting bears the scars of his soul. The longer he lives, the more grotesque the portrait becomes. Yet he hides it, refusing to let anyone see what his life is producing. He remains charming at the dinner table and untouchable in polite society. The man admired in salons is not the man revealed in private.

When Wilde imagined Dorian Gray’s portrait hidden away in an attic, quietly absorbing the scars of his moral decay, he offered more than a Gothic plot device. He gave us a disturbing image of what happens when beauty and approval conceal the slow undoing of the soul. I have come to recognize that portrait in the language we use about leadership, particularly in the glowing reverence for servant leadership. The model is widely praised for its humility and moral seriousness, yet it often hides a dark side. We admire the young and radiant Dorian. We seldom ask what is being concealed upstairs.

The Glow of Virtue

In the decades since Robert Greenleaf first introduced servant leadership in the early 1970s, its rise has been understandably remarkable. Greenleaf was a seasoned organizational insider. After a long career at AT&T, he became convinced that modern institutions were facing a crisis of legitimacy and a failure of moral imagination. In 1970, he published an essay titled “The Servant as Leader,” offering a simple provocation: the healthiest leaders begin not with the instinct to control but with the desire to serve. His vision emerged from the turbulence of mid-century America and a growing distrust of institutions that seemed powerful yet unaccountable. Servant leadership was not originally a technique. It was a critique and a call to rebuild institutional life from the ground up. In the years since, business schools have championed it, denominations have built entire frameworks around it, and non-profits have drawn inspiration from its moral seriousness. Servant leadership has become the gold standard of ethical leadership, a kind of moral North Star.

The promise of servant leadership is worthy. Greenleaf emphasized listening and empathy, and a desire to serve first. He offered a model of leadership grounded in mutuality rather than dominance, in fostering the growth of others rather than building personal résumés. His famous benchmark is still compelling: Do those served grow as persons? Do they become freer, wiser, more innovative?

But something happened on the way to the boardroom. Servant leadership became a brand, something leaders perform rather than embody. In many organizations, being seen as a servant leader now offers not humility but credibility, a moral certification that shields a leader from critique.

The ideal of servant leadership too often becomes a public performance. Leaders, especially in religious and non-profit spaces, learn the gestures and phrases of the humble servant as a way of concealing an exercise of power that remains centralized, unchecked, and sometimes harmful.

What happens when this sleight of hand takes place? When the language of service becomes a shield, and when apparent humility masks unexamined hierarchies and power dynamics that remain firmly in place?

The stakes here are not theoretical. When a leadership culture rewards virtue-signalling over truth-telling, institutions begin to spend the relational currency they most need for their work—namely, trust. In churches, schools, and charities, trust is a kind of social capital that sustains the neighbourly economy. It is what allows volunteers to keep showing up, staff to stay when the work is difficult, donors to give without suspicion, and communities to tolerate the ordinary friction of living together. When trust erodes, the cost is not merely lower morale. The cost is the slow privatization of communal life, where people retreat into self-protection and institutions drift toward control because they no longer know how to cultivate consent.

When humility becomes an image to cultivate rather than a lived ethic, authoritarianism can settle in unnoticed. When service is preached from the top down, it is often those at the bottom who are expected to carry its weight. This is the illusion of virtue: a leader celebrated for being “a servant first” may, in practice, reinforce the very hierarchies the model was meant to subvert.

The glow of virtue, when unexamined, casts long shadows. A leader known for being virtuous becomes difficult to question. Feedback is stifled. Accountability blurs. Communities and institutions that profess servant leadership may unconsciously shift their focus from renewal and repair to mere performance. In such contexts, the leader’s self-conception becomes the centrepiece, even as those being “served” struggle under the unacknowledged weight of deference.

The unexamined performance of virtue exacts a cost, both from the leader and from the community.

In Wilde’s novel, Dorian Gray makes a habit of appearing virtuous. He speaks eloquently, donates generously, and dazzles his social circle. Meanwhile, hidden in the attic, the painting grows monstrous. He cannot bring himself to destroy it, or even to face it. Not until the final pages does he stab the portrait, hoping to break free. Instead, it is Dorian who dies, and the portrait returns to its original, unspoiled form.

This, too, is a warning for leadership. An image cannot carry contradiction forever. The unexamined performance of virtue exacts a cost, both from the leader and from the community. Sooner or later, what has been hidden makes itself known.

The Portrait in the Attic

Social scientist James C. Scott offers a helpful framework for understanding this dynamic. In Domination and the Arts of Resistance, he distinguishes between the “public transcript” and the “hidden transcript.” The public transcript is the outward performance of power relations, what a community says it believes about itself, how it narrates authority, consultation, and legitimacy. The hidden transcript is the backstage reality, the suppressed voices, the quiet critique, the subversive stories told when those with less power can finally speak without consequence.

In the public transcript, servant leadership presents a polished image: morally upright, altruistic, secure in ethical standing. The leader’s posture, words, and rituals are crafted to project humility and care. But behind closed doors, in the hidden transcript, power may be exercised in more unquestioned, traditional, and authoritarian ways. Scott argues that the hidden transcript is often a form of resistance, the space where the dominated critique, parody, or reinterpret the dominant script.

Scott notes that subordinates do not merely accept domination. They develop an alternative account of reality, often private, sometimes humorous, sometimes bitter, sometimes faithful, but almost always constrained by fear of retaliation. In faith-based and mission-driven organizations, these contradictions can be especially sharp. Staff may speak one way in official meetings, praising the leader’s humility, while sharing misgivings privately about manipulation, exclusion, or control.

If you have worked in such systems, you already know how hidden transcripts form. They form in the parking lot after a meeting when someone quietly says, “Well, that was decided before the meeting started.” They form insider texts during a Zoom call, a quick message that reads, “Did you hear what he just did?” They form in the breakroom when a colleague explains the real rules, the rules nobody names in the handbook. They form as jokes that carry real truth. “Our process is so discerning,” someone says, and everyone laughs, because everyone knows the conclusion has been pre-arranged.

These hidden transcripts are not always malicious. Often, they are an act of survival, the only available space for honesty. But they are also a measure of institutional health. When the only safe place to speak truth is outside the room, something is wrong inside the room.

Scott’s insight is critical here: the hidden transcript does not mean insubordination. It reveals the internal cost of maintaining an illusion. When leaders are uncritically celebrated for being servants, those beneath them may be asked to live in dual realities, upholding the myth while navigating the harm.

Over time, that burden accumulates. Institutions develop rituals of compliance that create a false consensus. Leaders grow more confident in their virtuous image, while the hidden transcript festers. Like Dorian Gray’s portrait, the moral cost is hidden until it becomes unbearable.

The antidote, Scott implies, is not simply to drag the hidden transcript into the open with confrontation. That approach can become its own performance. The deeper remedy is to create the conditions where hidden transcripts are less necessary: where power can be named, shared, and discussed without punishment; where dissent is treated as a gift rather than disloyalty; where leaders develop the spiritual maturity to hear what they do not want to hear.

The Bishop’s Hat

In a quiet corner office of a denominational leader hangs a mitre, a bishop’s hat, made of ivory felt and trimmed in gold. It was a joke, a gift from a long-time friend after a particularly triumphant committee vote. “For your episcopal leanings,” the friend had said with a wink. The mitre hangs near the bookshelves, just above framed diplomas.

This man—let’s call him Thomas—served in his middle judicatory role for nearly two decades. He is admired for his composure and modesty. In public, he is the image of deference. In committee meetings and governing-body gatherings, he speaks quietly, always insisting that he is there only to serve the body. He quotes Robert’s Rules with ease. He teaches seminarians that the polity of the church is a safeguard against clericalism, a way of protecting the people of God from domination.

But in private the decisions are often already made. Before a vote is taken, Thomas has met quietly with the right leaders. Before a pastor is called, Thomas has vetted the field. When dissenting voices surface, they are invited into long pastoral conversations in which concerns are patiently absorbed, thanked, and then shelved. There is never a raised voice, only careful arrangement.

Those who work with Thomas know this. They admire his intelligence, even his gravitas. But in hushed tones they call him “the bishop.” Not because he wears robes or issues decrees but because everything moves through him. And while he may not see it, his leadership has come to resemble exactly what he teaches against: authoritarian control cloaked in collegiality, spiritual dominance disguised as polity.

The consequences are rarely dramatic. They are quieter than that, which is part of the danger. Committees become timid. Younger leaders learn that “discernment” is often a synonym for permission. Pastors stop bringing hard truths upward because they can feel, without anyone saying it, what kinds of concerns will be received and what kinds will be redirected. The governing body continues to meet, continues to vote, continues to speak the language of process. But the body’s agency begins to thin out. When responsibility is shared only on paper, people eventually stop taking responsibility in practice.

To be clear, Thomas is not a cartoon villain. He loves the church. He may even believe, sincerely, that he is protecting it. After twenty years, he has become a stabilizing figure in a denomination that has known conflict, decline, and anxiety. Systems reward stability. Organizations often, though, confuse stability with health. It is possible to do genuine good while also consolidating power. That is precisely why the portrait is so hard to see. The mitre in his office has become more than a joke. It is the attic portrait. A symbol of the quiet consolidation of power that flourishes under the guise of service. He does not see the dissonance. But those around him do.

Servanthood and the Burden of the Margins

Theologian Jacquelyn Grant saw this contradiction long ago. She asked why the language of service is so often idealized when the people doing the serving are overwhelmingly poor, black, or from the global South. Her critique is searing: servanthood is not a moral virtue when it is demanded from the bottom and applauded at the top.

Grant’s point is not that service is wrong. Her point is that service becomes morally distorted when it is extracted rather than freely given, when it is praised as a spiritual ideal for those who have few alternatives, and when it functions as an ethical cover for inequality. In leadership education, we too often present servant leadership as a universal good without asking: Who is expected to serve? Who gets to lead while appearing humble? And who bears the cost of this illusion?

The result is a structural imbalance. Leaders receive praise for appearing humble, while others quietly perform the actual work of self-sacrifice. This imbalance is not simply an oversight. It is a feature of a leadership model that, when stripped of its original vision, rewards performing like a servant over meaningful change. Image replaces substance, and the portrait remains upstairs.

Service becomes morally distorted when it is extracted rather than freely given.

Servanthood, at its most authentic, calls for deep mutuality. This kind of mutuality requires relational trust, where power is not simply exercised responsibly but is also willingly shared. However, true mutuality cannot emerge when power differentials remain unaddressed or hidden beneath gestures of humility. No display of personal virtue can substitute for the structural courage required to redistribute authority.

In a faithful servant leadership model, the leader refuses to be the fixed point around which everyone else orbits. The work is not simply to invite participation but to yield real agency by opening decisions, influence, and responsibility to others. That kind of servanthood changes the shape of the room. It alters who sets the agenda, whose knowledge counts, and who can say no without consequence. When servanthood is reduced to a public posture, it stops being liberating and becomes managerial. Hierarchy remains, only now it wears a gentler face. What presents itself as care can function as quiet containment, dampening initiative, training people into dependence, and slowly thinning out the shared life it claims to nurture.

The Fragile Mirror of Formation

Leadership education must bear its share of responsibility. In our attempts to cultivate ethical leaders, we often tell students to emulate the servant leader. But we fail to interrogate the systems that elevate some and silence others. We focus on personal humility, not structural equity. We praise selflessness but do not ask who is being asked to disappear.

This moral focus is not inherently wrong, but it is insufficient. When students are told to “lead like Jesus” without being equipped to examine institutional complicity in racial, economic, and gender injustice, we do them a disservice. We teach them to polish the mirror and not to examine what lies behind it. A polished mirror can still reflect a distorted world.

Just as important as Greenleaf’s ideas was the form he chose to write them in. His early work was not a systematic leadership theory but a set of reflective essays. In writing as he did, Greenleaf was not merely offering content; he was modelling a discipline. He practiced a way of thinking, listening, and discerning in public, slower than a framework and more demanding than a slogan. The essays are deeply contextual, shaped by a social landscape he found increasingly fractured. His central question was not “How can a leader be seen as virtuous?” but “How can a leader be of use to a society in pain?”

In Greenleaf’s vision, the servant leader is a listener, a healer, a practitioner of mercy in public life. Yet as his work became institutionalized, particularly in business schools and religious circles, his questions were translated into formulas. Presence became posture. Empathy became technique. And the attic door quietly closed.

To recover the formative power of Greenleaf’s vision, leadership programs must move beyond case studies and behavioural rubrics. We must cultivate the habit of asking who benefits, who is silenced, and what kind of community is being made in the wake of leadership. These are spiritual and ethical questions, not merely organizational ones.

Rethinking Leadership Education: A Path Toward Renewal

To reclaim servant leadership from its cosmetic distortions, leadership education must evolve. We cannot be content with teaching aspiring leaders how to appear humble. We must challenge them to examine the systems they inhabit and the unconscious privileges they carry.

This work begins with storytelling, because narrative has the power to reshape us. But I am not referring to the familiar stories of heroic leaders triumphing over adversity. What we need instead are stories of communities empowered, of shared decision-making, of leadership reimagined in non-traditional and relational ways. The classroom must become a space where voices from the margins are not just included but centred. Curriculum should move beyond the classic texts to embrace the contextual and lived experiences of those who have long been excluded from the leadership table. These are the stories that disrupt inherited hierarchies and invite a more just and generative vision of leadership.

Furthermore, reflection must move beyond the personal to the systemic. Students should be asked not only to write about their leadership values but also to audit the institutions they lead or aspire to lead. What forms of labour are invisible? Who is expected to perform self-sacrifice, and who is rewarded for it? What power dynamics are being reaffirmed in the name of service?

There are concrete ways to make this practicable. Students can be taught to do a simple “power map” of an organization, not from cynicism but for clarity: who can say no, who sets agendas, who controls information, who bears risk, who receives praise. They can be asked to track decision pathways in their own institutions and to name where consultation is real and where it is ceremonial. They can practice what it means to share authority by designing collaborative processes that actually redistribute responsibility. It is one thing to invite participation. It is another to change who can shape an outcome.

Faculty, too, must model what it means to be vulnerable and curious. Leadership educators cannot merely critique from the outside; they must examine their own classrooms, their syllabi, and their assumptions. In doing so, they invite students into a posture not of certainty but of pilgrimage. In a culture intoxicated by certainty, the discipline of honest not-knowing is itself a form of service.

Pedagogies of discomfort, in which students wrestle with the tensions between their ideals and the complexities of real systems, are essential. Servant leadership, taught well, should unsettle everyone in the classroom. It should expose the fragility of image and the hunger for approval. It should strip away the performance and reveal the ethical struggle underneath.

Finally, leadership programs must resist the pressure to turn servant leadership into a marketable tool. Institutions that frame it as a productivity strategy or morale booster are missing the point. Greenleaf’s challenge was not to optimize systems but to reimagine them, to raise new questions, to listen to the silenced, and to lead with love, even at the cost of power.

A More Honest Light

Again, Greenleaf did not set out to create a model for moral performance. He saw a broken world and broken institutions and sought a different path. He called for leadership that heals, listens, and empowers.

To recover the soul of servant leadership, we must be willing to ask harder questions. We must stop shielding the model from critique. We must unmask the rhetoric when it serves to obscure, and we must restore the focus on those being served: Do they grow? Do they flourish? Do they become free?

Dorian Gray could not ignore the portrait forever, and neither can we.

To look into the attic is not to reject the beauty of Greenleaf’s vision. It is to admit that any vision, left unexamined, can harden into an image we learn to protect. Power has a way of polishing our self-understanding until it shines. The attic is where that shine is tested. In that sense, the attic is not where servant leadership ends. It is where it begins again, with steadier eyes.

For practitioners, this renewal need not remain abstract. It can take the form of institutional habits that make truth speakable and power shareable. Governing bodies can insist on decision transparency, not as paperwork, but as a discipline of shared life. Leaders can name who shaped an agenda and why. Organizations can build protected channels for dissent, and then prove, in public, that disagreement does not trigger reprisal. Communities can practice repair when harm has been done, not with public relations, but with honest acknowledgement and tangible amends.

When servant leadership is reclaimed as mutuality, accountability, and shared responsibility, it begins to restore what institutions quietly spend and rarely notice until it is gone: trust. It widens the room. It loosens the grip of fear. It makes it possible for people to stay at the table without surrendering their voice.

The portrait will always exist. The question is whether we will climb the stairs together, open the door, and let the truth have its say. Then comes the harder mercy, to live differently after we have seen what it reveals.